Stephen Adkins, chief of the Chickahominy Indian Tribe of Charles County, Virginia, could not be happier: Monday, President Donald Trump signed legislation granting federal recognition to the Chickahominy and five other Virginia tribes.

“I’ve been working for congressional recognition since 1999, and here we are,” he said.

The Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017 recognizes the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Monacan and Nansemond tribes as sovereign nations, bringing to 573 the number of federally-recognized tribes in the U.S. In 2016, the Pamunkey Indians became the first Virginia tribe to be granted federal recognition.

As such, the tribes can now create their own laws, collect taxes and manage their lands.

“This was clearly the right thing, acknowledging the sovereignty of these six Indian tribes whose history predates the arrival of the first English settlers at Jamestown,” said Adkins, who can recite the history of the Chickahominy back hundreds of years.

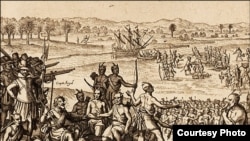

“Our history is similar to all the other Indians in Virginia at the time. We were part of the welcoming party [of about 30 tribes] that greeted the first English settlers in May 1607. We had the mental acumen, the efficacy of the bow and arrow, opposite the clumsy musket. We could have taken those settlers out on the first boatload, the second boatload, the third boatload.”

But they didn’t.

Instead, the Chickahominy ("The Coarse Ground Corn People") and other tribes of the paramount chiefdom ruled by Powhatan traded with settlers and taught them how to grow and preserve their own food. Later, the Chickahominy renounced their allegiance to Powhatan and allied themselves with the settlers.

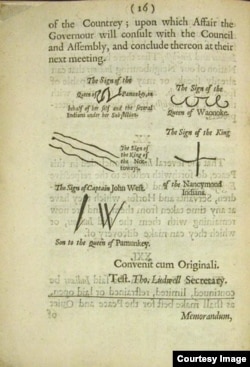

“We agreed to provide 350-500 bowmen to the settlers in the event of an attack by the Spanish,” he said. In 1677, the Chickahominy and several other Virginia tribes signed a peace treaty, pledging fidelity to the British Crown in exchange for protection.

“Later, when the United States was formed, there was no move to engage those treaties or enter new treaties. And we never took up arms with the United States, so consequently, we never signed a treaty with the United States.”

A long time in coming

Normally, tribes wanting to be recognized must petition the Department of the Interior’s (DOI) Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). But because Virginia tribes made peace deals with England more than a century before the U.S. was founded, they can’t document government-to-government relationships, something the BIA demands.

The BIA also requires tribes to present genealogies of all members.

“Many times, those documents just don’t exist,” said Arlinda F. Locklear, a Washington, D.C. lawyer who has represented tribes seeking recognition. She is a member of the Lumbee tribe from North Carolina, which is not recognized by the federal government.

“For example, over the generations, one of the strategies of survival for a lot of tribal communities has been to hide away and make themselves invisible to the dominant society, in which case, there aren’t many records generated on them.”

During the Civil War of the 1860s, she explained, many southern courthouses were burned, and records thus destroyed.

Then, in the 1920s, Virginia passed the Racial Integrity Act, requiring Native Americans to classify themselves as “black,” making it nearly impossible to prove their Indian ancestry.

In 1999, the tribes turned to Virginia lawmakers for help.

In February 2017, Virginia Congressman Rob Wittman introduced the recognition bill to the House, where it passed in May. The Senate version, co-sponsored by Virginia Senators Tim Kaine and Mark Warner, passed unanimously January 11.

‘Stamp of approval’

The six tribes are now eligible for federal assistance in education, health care and housing, at a projected cost of about $67 million during the next four years, assuming Congress appropriates the funds.

The new law also calls for the DOI, if the tribes request it, to take their lands into trust for the benefit of the tribes, whose members collectively number about 4,400. It will not alter hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering or water rights of the tribes and their members. It also prohibits the tribes from conducting any gaming activities.

But more important than the benefits is recognition itself, said attorney Locklear. “You cannot overstate the political and social importance of this,” she said. “These Indian communities have labored under the misapprehension that they were somehow not real because they have lacked federal recognition ... Now that they’ve got that stamp of approval.”

As for Adkins, he said over the years, he never gave up hope.

“I have a strong faith in God and I have faith in the democratic process. I believe that ultimately that United States does the right thing, and this was clearly the right thing.”