Editor’s note: November is Native American Heritage Month. First proclaimed by President George H. W. Bush in 1990, it is an opportunity to acknowledge the histories and cultures of Native people across the U.S., highlighting the challenges they have faced, their sacrifices and their contributions.

“Native Americans have influenced every stage of America's development,” noted President Donald Trump in his October 31, 2017 proclamation. “They helped early European settlers survive and thrive in a new land. They contributed democratic ideas to our constitutional framers. And, for more than 200 years, they have bravely answered the call to defend our Nation, serving with distinction in every branch of the United States Armed Forces.”

Throughout November, VOA will highlight some of the more prominent figures in Native American history and their contributions to language and culture.

Pocahontas is perhaps the most widely-known figure in Native American history, popularized in fiction and romanticized by Hollywood as a beautiful and demure American Indian “princess” who sacrificed herself to the interests of British colonials and ultimately saved England’s first Virginia settlers from “death, famine and utter confusion.”

Likely, none of that is true.

Born Amonute, she was the daughter of Pamunkey Chief Wahunsenaca, who led an alliance of about thirty Algonquian-speaking tribes and bands in eastern Virginia at the time British adventurers first arrived in 1607.

This did not make her a “princess,” royalty being a European concept. Her family called her Matoaka, “flower between two streams,” which likely referred to their home between Virginia’s Mattaponi and Pamunkey Rivers.

Tradition has it that her father also called her “Pocahontas,” which has been translated in many ways throughout history, from “wanton” to “mischievous,” all pointing to a lively personality.

Little is known of her childhood. Dr. Linwood “Little Bear” Custalow, a member of the Mattaponi tribe which was historically part of Wahunsenaca’s confederation, wrote that according to Mattaponi oral history, Matoakoa married a young Potowomac warrior named Kocoum when she was about 14. They had a child called Little Kocoum, who survived and was raised among the Mattaponi. Custalow also states that the English murdered the child’s father, and today, a number of families claim to be his descendants.

In 1613, the English abducted Pocahontas as a bargaining chip in negotiations with her father and held her for a year at their settlement at Jamestown.

At some point during her captivity, the English baptized her and gave her the Christian name “Rebecca.” Whether she converted voluntary is not known. According to the Mattaponi, at one point the English settlers allowed her sister to visit her, and Pocahontas spoke of having been raped.

During her time at Jamestown, a British tobacco planter named John Rolfe took an interest in her. The details of their relationship are hazy. In his writings, Rolfe made it clear he loved Pocahontas but also recognized the benefits of a marriage alliance between Britain and Virginia tribes.

Rolfe married Pocahontas in 1614, and she gave birth to a son, Thomas. The Mattaponi say her father did not attend the wedding, but gifted her a necklace made of pearls harvested from Virginia's coastal waters.

Pocahontas traveled to England with Rolfe and Thomas in what today could be viewed as a promotional tour for the new Virginia colony. She was presented to the Queen as Virginia’s first Christian, and by all accounts was well-received.

But Pocahontas fell ill before she and Rolfe could make the journey back to Virginia. She was buried at St. George’s Church in the Kent town of Gravesend on March 21, 1617. A memorial statue stands there today.

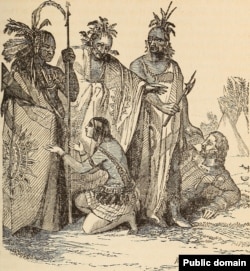

Pocahontas is most famous for something which likely never happened: Saving British explorer Captain John Smith from execution by Chief Wahunsenaca in 1607.

Smith claimed that he had been taken prisoner by a group warriors who dragged him before Chief Wahunsenaca and were ready to “beat out his brains” with club. But, he wrote, Pocahontas threw herself down on top of the prisoner and thereby saved his life.

Today, the Mattaponi say it could not have happened, as the event isn’t consistent with Virginia Native culture or custom. Non-Native scholars view the story skeptically, taking note that even in his own time, Smith was viewed as conceited and boastful, prone to exaggerating the facts.