When the English arrived in Virginia in the 1600s, the Pamunkey were one of the most powerful tribes of the Powhatan federation led by Chief Wahunsenacawh Powhatan – remembered today as the father of the Pocahontas.

Gaining federal recognition was a Herculean task, said Pamunkey Chief Robert Grey.

“We see recognition as access to certain government programs that could help us stand on our own two feet as a sovereign nation. It’s just the fact that the government acknowledges us and that we actually got through such a tough procedure,” he said.

The U.S. government recognizes 567 tribes, mostly through historic treaties. Non-treaty tribes who want recognition must petition the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) and meet strict requirements.

“By meeting each criterion, a group is demonstrating that it has continued existence, both socially and politically, from 1900 to the present, and that the group descends from a historical Indian tribe or tribes,” said Nedra Darling, public affairs director for DOI’s Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, in an emailed statement. “The regulations define ‘historical’ as pre-1900.”

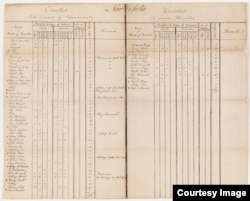

Tribes must document that they have continuously operated as autonomous entities for more than a century. They must list all members, documenting individual genealogies that show direct descent from individuals listed in 19th century federal Indian registers.

This often requires petitioning tribes to seek help from professional historians, archaeologists and genealogists, at considerable cost; the Pamunkey spent close to $2 million on their petition, something smaller tribes may not be able to afford.

Access to benefits

Why go through such a complex, tedious process?

“The benefit of becoming a federally recognized tribe is the ability to work with the federal government through a government-to-government relationship,” said Nedra Darling, director of public affairs for the office of the Department of the Interior’s Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs.

Recognized tribes function as sovereign nations, protected from state and local jurisdictions. Their lands cannot be taken away or sold. They may administer their own funds, set up their own police forces and licensing systems. They pay the same federal income tax as other U.S. citizens.

“Once the group has obtained federal recognition, they are eligible for federal programs that benefit their tribal citizen’s needs,” said Darling.

Programs, said Chief Gray, which his tribe sorely needs to grow.

“We see recognition as having access to certain government programs that could help us stand on our own two feet as a sovereign nation,” he said.

To wit: shortly after it was recognized, the tribe received a $50,000 government federal grant toward building affordable housing.

‘Paper genocide’

Of the approximately 20 tribes in Virginia, only the Pamunkey have been federally-recognized. A few others are currently working toward recognition, and some do not qualify at all. Virginia recognizes six tribes besides the Pamunkey. In 2011, they collectively appealed to DOI to relax its standards.

They cite, for example, Virginia’s 1924 “Racial Integrity Act,” a racist law that required every child born in the state to be classified as either “white” or “colored.” It defined “colored” as having “one drop” of non-white blood and lumped people of both Native American and African descent together. It was repealed in the 1960s, but Virginia Indians trying to prove their ancestry run into a 40-year gap in records, calling it “genocide” by paper.

Tribes may bypass DOI and directly petition Congress to be recognized. Virginia Senators Mark Warner and Tim Kaine have reintroduced legislation to recognize the six state-recognized tribes, citing the “systematic destruction” of Indian records. The bill has been pitched at least a dozen times since 2000, but has always stalled in the Senate over worries that relaxing DOI standards could allow fraudulent “tribes” access federal funds.