All across Indian Country, Native Americans are being evicted from their tribes, with little warning and little legal recourse.

Take, for example, the Pechanga Band of Luiseno Mission Indians, a federally-recognized tribe of Luiseno Indians living on a reservation in Temecula, California, part of the territory where their ancestors lived for 10,000 years.

If you want to be a member, you must prove direct lineage to one or more of the original ancestors forced onto the reservation in the early 1880s.

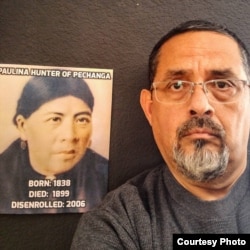

Pechanga Indian Rick Cuevas traces his ancestry to a woman named Paulina Hunter, who was granted a lot of land on the Pechanga reservation in the late 1800s. He and his family have lived on the reservation as full tribal members for decades.

But in the early 2000s, the tribal council decided to posthumously disenroll Hunter and, by extension, about 180 of her descendants.

“They have desecrated the memory of our ancestors,” Cuevas said. “The Pechanga tribal chairman has ripped our history from us, without evidence. And yet his ancestor, back in the day, called my ancestor ‘Aunt.’”

More than 1,000 kilometers to the north, a member of Oregon’s Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde told VOA a similar story. Her family enrolled in the tribe in 1986. But two decades later they received notice that without proper documentation of lineage, they would be disenrolled.

Her great, great, great grandfather was among the original signatories of an 1855 treaty that ceded ancestral lands to the U.S. government and established the Grand Ronde reservation. He was killed before he moved to his new home. That meant his name never made it to a later census roll – a key requirement for “belonging.”

The family eventually won a three-year battle in tribal courts and regained their membership, but victory came at a cost.

“My cousin died a few months before her 99th birthday, before we were restored to the tribe,” the woman said. ”She grew up in a time when Indians were called bad names, had rocks thrown at them [by whites]. She always called Grand Ronde the only Indian home she’d ever known.”

She paused, then added: “My one regret in all this is that she didn’t live to see our membership restored.”

A way out of poverty

Disenrollment is an epidemic in reservations across Indian country. Cuevas tracks these cases on his Original Pechanga website: So far, 11,000 Indians have been exiled from dozens of tribes. In one of the more extreme cases, tribal members living off California’s tiny Elem Pomo colony attempted to disenroll every Elem Pomo Indians living on the colony – among them, the last living speaker of the Elem Pomo language.

As it turns out, this and the majority of other disenrollment cases are about money.

In the 1960s and 70s, substandard conditions on reservations led some tribes in to look to gambling as a solution. A 1987 Supreme Court decision gave them the legal green light to open up bingo halls, poker games and casinos, and a year later, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, laying out the rules.

Today, more than 200 tribes operate casinos that range from small card or bingo operations to large-scale resorts rivaling any in Las Vegas. Collectively, they earned nearly $39 billion in 2015. They are not taxed on that revenue but must use it to fund tribal governmental services, economic and community development and charity.

Some of the more prosperous gaming tribes distribute per capita payments to tribal members as part of a “revenue allocation plan.” The more members, the smaller the individual allocations, and this has often led to angry dissent over who is eligible and who is not.

“Say you are a small tribe of, say, 100 members, and your casino is doing very well,” said Gabe Galanda, a Seattle lawyer of Nomlaki/Concow descent who specializes in disenrollment disputes. “Say you are getting $5,000 in gaming revenue a month, and you have 100 tribal members – basically, 99 relatives. If you can get rid of 50 of your relatives, your monthly per capita income just went up to $10,000 a month. And this has caused certain tribal communities to divide and conquer themselves.”

Cuevas’ tribe operates the Pechanga Resort and Casino, the largest in California. By some estimates, it earns from $1-2 billion annually and pays allotments to each tribal member of $300,000 or more a year.

Cuevas estimates that his family has lost more than $2.5 million per person in per capita payments alone in the 11 years since they were disenrolled, assuming the per capita rate at that time.

But money isn’t the only thing he has lost. Some losses can’t be quantified.

“We were tribal members long before the casino came,” he said. “Our family has resided on the reservation continuously for nearly 70 years.”

Today, disenrolled members are denied health and educational benefits.

“And they can’t be buried in the reservation cemetery with their relatives and ancestors,” Cuevas said.

The Pechanga Band government did not respond to VOA’s request for comment.

An alien concept

Disenrollment is not native to indigenous cultures, who Galanda said traditionally understood “belonging” in terms of kinship and personal choice, not “blood quantum,” a measurement introduced by the U.S. government.

“The U.S. introduced its concept of who’s an Indian by declaring, under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, that an Indian must be in residence in a reservation likely established by the treaties of the 1800s and be of one-quarter Indian blood,” he said. “The challenge today is that many tribes, if not most tribes, use the Federal government’s criteria for who’s an Indian.”

Disenrollment is also happening in tribes that have no disposable gaming wealth, said Galanda.

“Say I’m a chairman, and there is a voting block that I do not like or cannot win over. If I eliminate that voting block through disenrollment, I will sustain my power and the wealth that goes with that power,” Galanda said.

Disputes over enrollment, whether motivated by dollars or vendetta, can be devastating.

“It deprives that person of their identity, in addition to exiling them. It is in my estimation identity theft,” he said.

An internal problem

For a variety of complex legal reasons, tribes in some states have their own courts, but tribes in others - in California, for example - are adjudicated by state courts.

“I, too, have declined these cases,” Stephen Pevar, a senior staff attorney in the American Civil Liberty Union’s Racial Justice Program, said in an email, “not because I want to, but because there is no remedy available in a court. There’s nothing a state or federal court can do.”

To wit, this week, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear a disenrollment case involving another Calfornia tribe.

In the end, said Pevar, the onus is on tribes to settle these disputes for themselves.

There is precedent: This week, California’s Robinson Rancheria of Pomo Indians reinstated several dozen members who were disenrolled nearly a decade ago by corrupt tribal leaders who left the tribe millions of dollars in debt.

“Hopefully, after this week, we can just move forward,” said tribal chairman Eddie Crandell.

His tribe is still divided, and he laughs, admitting there are some folks he would not mind expelling. But that would be a lazy way to deal with tribal factionalism.

“Indian people, we’re such a small group in the United States. We shouldn’t be trying to eliminate ourselves but embrace ourselves,” Crandell said.

And he sent out this message to tribes embroiled in enrollment disputes:

“Bring your people home and work together to restore Mother Earth, to restore our culture and move on from your collective, inherited trauma.”