Editor’s note: November is Native American Heritage Month. First proclaimed by President George H. W. Bush in 1990, it is an opportunity to acknowledge the histories and cultures of Native people across the U.S., highlighting the challenges they have faced, their sacrifices and their contributions.

“Native Americans have influenced every stage of America's development,” noted President Donald Trump in his October 31, 2017 proclamation. “They helped early European settlers survive and thrive in a new land. They contributed democratic ideas to our constitutional framers. And, for more than 200 years, they have bravely answered the call to defend our Nation, serving with distinction in every branch of the United States Armed Forces.”

This month, VOA will highlight some of the more prominent figures in Native American history and their contributions to U.S. language and culture.

No portrait exists of the woman who has come to be one of the most celebrated Native Americans in U.S. history books. Meanwhile, scholars and tribes don’t even agree on the details of her life.

The Lemhi-Shoshone tribe says she was born near what is today the town of Salmon, Idaho, in 1788 and that her name may have been Sacatzahweyah, “a burden that must be pulled or carried.” They say that in 1800, when she was only about 12, Sacagawea was among several Shoshone girls who were kidnapped by raiders from the rival Hidatsa tribe and taken to what is today North Dakota.

She may or may not have been won in a gambling game by French-Canadian trapper, Toussaint Charbonneau, a man with an unsavory reputation. He would call Sacagawea his “wife.”

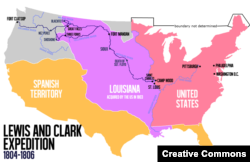

But we do know that in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson purchased nearly 830,000 square miles of new territory and commissioned an expedition to explore it and map out a possible new trade route to the Pacific Ocean. The 33-member Corps of Discovery, as it was called, was headed by two men-- U.S. Army Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lt. William Clark, who kept journals of the mission and provide some of the only definitive written information about Sacagawea.

The expedition set out from the Mississippi River in May 1804. Six months later, they arrived in North Dakota, where they met Charbonneau and Sacagawea.

The Corps hired Charbonneau as an interpreter. It would have been highly unusual to bring a woman on such a voyage—but Lewis acknowledged that Sacagawea would be useful when it came time to buy horses from the Shoshone, which they would need to cross the Rocky Mountains.

The Corps built a winter fort in North Dakota spent the next few months planning the voyage. In February 1805, Sacagawea gave birth to a baby boy, Jean Baptiste, whom Clarke would nickname Pompy.

Eight weeks later, the expedition continued.

History has cast Sacagawea in the role of pathfinder. In reality, her role was far less important, but not insignificant: As a teenager, she would already have learned most of the skills necessary to survive – hunting, fishing, butchering and skinning animals, tanning leather, harvesting wild berries and prairie turnips, sewing and cooking. She made herself useful to the men, gathering wild foods to supplement their diet or repairing and sewing clothes and shoes—all the while caring for an infant son.

Clark acknowledged that the presence of Sacagawea and a baby had a soothing impact on both explorers and the tribes they encountered along the way—after all, no war party would travel with a woman and child.

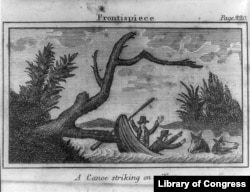

Once, when a storm nearly capsized one of the expedition’s boats, Sacagawea dove into the water and retrieved important papers and supplies, for which Clark was grateful.

But considering she traveled nearly a year with the corps, she is given comparatively little mention in their writings, usually referred to in terms of her secondary role as the trapper’s “wife.”

When they finally reached the Pacific, Sacagawea had to beg the men to allow her a glimpse of the ocean. The government paid Charbonneau for his services but gave Sacagawea nothing.

“This man has been particularly serviceable to us, and his wife particularly useful among the Shoshonees,” wrote Clark, crediting her at least with patience on the long, difficult trip.

Sacagawea was never recognized in her own time and was nearly forgotten to history. But in the early 1900s, an early feminist resurrected Sacagawea in a fictionalized account of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Romanticized as the “beautiful Indian captive” who would “unlock the Gates of the Mountains,” Sacagawea became an icon of the women’s suffragist movement.

Today, statues and memorials to Sacagawea can be found in several states, and historians and tribes continue to debate who she really was and what happened to her after the expedition concluded.

By most accounts, Sacagawea gave birth to a daughter and died in 1813.

But the Hidatsa say she was never Shoshone, that she was one of their own and that she lived into her 80s. Today, Hidatsa, Shoshone and even Comanche families claim descendance from her.

And the Lemhi-Shoshone, who today live on the Fort Hall Reservation in Idaho, are still fighting for federal recognition. They view America’s celebration of Sacagawea as a “slap in the face.”

As a great-great-grand nephew of Sacajawea Snookins Honena put it before his death in 2017, “The feeling we get here is ‘We don’t want you here, but we want your Sacajawea heritage.’”