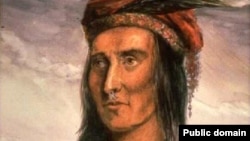

Tecumseh was a 19th century leader of the Shawnee tribe who led a large, multi-tribal confederacy to fight American expansion into the Northwest—ultimately in vain.

Born in western Ohio around 1768, Tecumseh grew up during a period of constant warfare, as white settlers pushed inland from the Atlantic Coast into the Midwest. The Shawnee had once lived in the woodlands east of the Mississippi River, but had by that point had been pushed to what are today the states of Ohio and Indiana.

According to the Eastern Shawnee Tribe’s website, Tecumseh’s father died in battle with Virginia militiamen in 1774. Tecumseh was raised by his elder brother, who trained him as a warrior.

In his first battle, at the age of 14, the Shawnee say Tecumseh panicked and ran from the field. He was so humiliated that he made up his mind to never shy away from battle again.

He is known for inflicting the most punishing defeat of American troops. In the late fall of 1790, his forces attacked an encampment of American soldiers in western Ohio, leaving more than 600 dead and hundreds wounded; it was the biggest defeat of the U.S. army ever.

Around 1805, Tecumseh’s younger brother claimed to have had a series of visions and took on a new name: Tenskwatawa, which means “Prophet.” In modern terms, he was a religious fundamentalist who preached against Shawnee assimilation of white culture.

Tecumseh worked to promote his brother’s revivalist vision, which promised protection against white soldiers and predicted the return of the traditional Shawnee way of life.

The two brothers established the village of Tippecanoe in what is today Indiana. It was intended to serve as the headquarters of a new pan-Native alliance against the U.S. The Americans named it “Prophetstown.”

Tecumseh then began a series of travels as far north as Canada and as far south as the U.S. Gulf Coast, politicizing and spreading his brother’s message in his effort to recruit tribal allies.

By the spring of 1810, white settlers had grown increasingly nervous over rumors that the tribal alliance was planning to attack and kill not only them but the American governor, headquartered in the city of Vincennes in Indian territory.

Other rumors began to circulate. In one, Indiana Territory governor William Henry Harrison challenged the Prophet’s divine powers by challenging him to a miracle: “If he is really a prophet, ask him to cause the Sun to stand still or the Moon to alter its course, the rivers to cease to flow or the dead to rise from their graves,” reads one 19th century account.

Tenskwatawa then promised that in fifty days, the Great Spirit would take the sun into his hands and darken the sky. And, as the story goes, on the appointed day, the sun disappeared behind the moon. Legend also has it that when the Creek tribe refused to join Tecumseh’s alliance, he threatened to stamp his feet and cause the ground to shake.

The only truth to these tales is that a total eclipse of the sun did take place in June 1806, and a series of three earthquakes rocked the Midwest over the winter of 1811-1812, devastating the Missouri River Valley.

In 1811, while Tecumseh was away on a recruiting trip in the South, the U.S. army set out on a march to attack “Prophetstown.” He sent a party of warriors out to meet them, and the two sides engaged in a two-hour battle which neither side won. The Prophet’s forces withdrew, and the next day, the Army burned Tippecanoe to the ground.

When the U.S. Congress declared war on Great Britain in 1812, Tecumseh and his allies sided with the British, believing that a British win would stop the advance of the Americans.Tecumseh is said to have distinguished himself as a cunning strategist who helped the British to victory in Detroit.

But in 1813, he was fatally wounded by American forces during the “Battle of Thames” in Ontario.

His death marked the end of the alliance and is seen has having opened the way for American expansion into the continental northwest. In the following years, the U.S. government forced tribes west of the Mississippi River to accept more than 200 treaties, establishing nearly a hundred reservations.

Once, the Shawnee were a unified tribe spread across numerous states in the U.S., Canada and even Mexico. Today, the government recognizes three branches, all living in Oklahoma—the Shawnee Tribe, the Absentee Shawnee Tribe and the Eastern Shawnee Tribe, all of whom remember Tecumseh as a hero.

William Henry Harrison, who would go on to become the ninth U.S. president, was impressed by the Shawnee leader. He described Tecumseh as “one of those uncommon geniuses which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions and overturn the established order of things.”