Editor’s note: November is Native American Heritage Month. First proclaimed by President George H. W. Bush in 1990, it is an opportunity to acknowledge the histories and cultures of Native people across the U.S., highlighting the challenges they have faced, their sacrifices and their contributions.

“Native Americans have influenced every stage of America's development,” noted President Donald Trump in his October 31, 2017 proclamation. “They helped early European settlers survive and thrive in a new land. They contributed democratic ideas to our constitutional framers. And, for more than 200 years, they have bravely answered the call to defend our Nation, serving with distinction in every branch of the United States Armed Forces.”

This month, VOA will highlight prominent Native Americans and their role in U.S. history, culture and society.

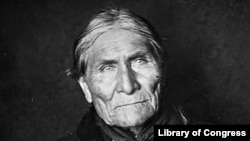

His given name was Goyahkla, “one who yawns,” but he later earned a nickname that has since become synonymous with battle.

Geronimo was born near the headwaters of the Gila River in what is today New Mexico sometime around 1829. He was the grandson of a chief and a member of one of four bands of Chiricahua Apache, the Bedonkohe.

Up until the 16th century, the Chiricahua homeland had stretched across 6 million hectares (15 million acres) in the U.S. southwest. But all that changed after Spain conquered Mexico and extended its domain well north into Apache territory. By the time Geronimo was born, the Apache had been fighting Spanish troops for more than a century.

At 17, he was admitted to the band’s war council and joined raids against Mexico.

A turning point came in 1858, when he and his band traveled to conduct trade in Casa Verde, Arizona, still held by Mexico at that time. They left their women and children camped outside of town, under guard. When they returned from their business, they found Mexicans had attacked and killed nearly everyone in camp, including Geronimo’s wife and three children.

“I could not call back my loved ones, I could not bring back the dead Apaches, but I could rejoice in … revenge,” he later said in a dictated autobiography. Geronimo joined forces with three other Apache bands to march deeper into Mexico, where they “captured, killed and scalped” in retaliation.

‘Manifest destiny’

James Polk was elected America’s 11th president in 1845. He believed in the concept of ‘manifest destiny,’ that it was God’s will to expand the U.S. as far as the Pacific Ocean.

America had already annexed Texas. Mexico had claimed everything to the west and refused to sell it to the U.S. So the U.S. declared war and won all or part of what is now ten western states, including the Apache homelands. Settlers began pouring into the region, sparking waves of sometimes brutal attacks by Apaches and earning them the reputation of “bloodthirsty savages.”

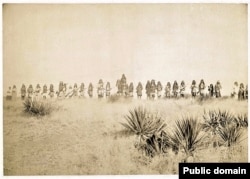

By 1872, the Chiricahua realized that they were fighting a losing battle. Their leader, Cochise, negotiated a peace agreement with the U.S. government, by which he agreed to stop fighting and move his followers to a reservation in their home territory.

But the government reneged on that agreement two years later, and forced several thousand Apache to a reservation at San Carlos, Arizona, a barren place that U.S. troops called “Hell’s Forty Acres.”

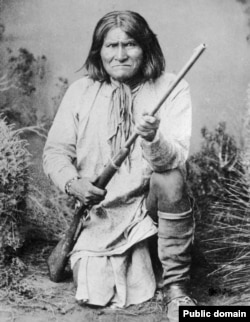

Outraged, Geronimo and a group of followers escaped. He would elude the Army for a decade, hiding out in the mountains or slipping back and forth over the border with Mexico.

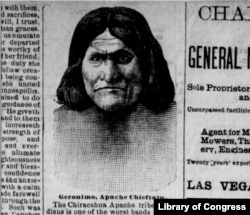

All the while, newspapers and magazines across the country roused audiences with tales of the “bloodthirsty” insurgent, vague on details but terrifying nonetheless.

In 1884, the government detailed an astonishing 5,000 troops to capture Geronimo and his band, aided by hundreds of Apache allies and volunteer militia. Geronimo, worn out from the chase, finally surrendered in late 1886.

The Army promised Geronimo he would not be executed but rather would be exiled for two years and then allowed to rejoin his family in Arizona. As it turned out, Geronimo would remain a prisoner of war for life.

Unfulfilled promises

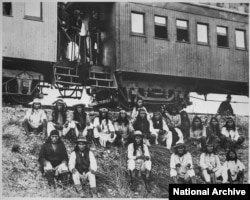

Geronimo was put to work at a military fort in Florida, where he was displayed to tourists.

A year later, he was sent to Alabama and finally, in 1894 was moved to Fort Sill in Oklahoma, where he converted to Christianity. He would never see his homeland again. He was allowed to attend fairs and exhibitions, always under guard, where he sold autographs and pictures of himself, saving “plenty of money—more than I had ever owned before.”

President Theodore Roosevelt invited Geronimo and five other Native leaders to ride in his 1905 inaugural parade. While in Washington, still under guard, Geronimo met with the president and asked to be returned to his homeland. Roosevelt turned him down.

Geronimo died of pneumonia on February 17, 1909, and was buried at Fort Sill.

Two days later, the Washington Post remembered Geronimo as “a bad Indian.” But it also noted that “no spirit of gentleness or justice prompts the invasion of another people’s lands…no spirit of brotherly love accompanied the rifle and the axe in their conquest of the ranges of the red man.”

If Geronimo was a monster, the editorial concluded, “civilization had a hand in making him one.”