The United States and Russia face significant obstacles in implementing an agreement to dispose of Syria's chemical weapons, regardless of whether the disposal happens inside or outside that war-torn country.

Earlier this month, Washington and Moscow agreed that Syria's estimated 1,000 tons of chemical munitions should be destroyed or removed by the middle of next year. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad pledged to cooperate.

Under the plan, inspectors from the Netherlands-based Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons would be deployed in Syria by November to supervise the process. But world powers have not agreed or disclosed how it would unfold from there.

Doing the Job in Syria

If those powers decide to destroy the stockpiles within Syria, the process likely would involve sending in specialized mobile units. Building a permanent facility to do that could take a year or more, dragging beyond the mid-2014 date by which the stockpiles are meant to be gone.

The United States and Russia could provide the necessary equipment. Both powers have more than a decade of experience in destroying their own chemical stockpiles. But neither has said if it would join a Syria-based operation.

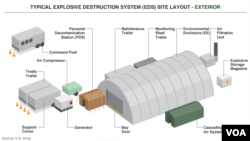

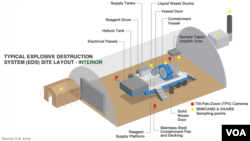

The United States has two types of mobile units for destroying chemical weapons - an Explosive Destruction System (EDS) that neutralizes munitions containing chemical agents, and a Field Deployable Hydrolysis System (FDHS) that neutralizes the chemical agents and their precursors in bulk.

The U.S. military has built five EDS units capable of handling several munitions at a time. It also unveiled its first FDHS unit in June, saying the system is "designed for worldwide deployment with operational capability within 10 days of arriving on site."

Problems with the Syria Option

U.S. counterproliferation analyst Al Mauroni told VOA that using U.S. Army EDS units to destroy munitions inside Syria would be slow.

"I don't think they could complete it within six months," he said.

Mauroni is director of the Alabama-based U.S. Air Force Counterproliferation Center, which educates Air Force leaders about how to deal with weapons of mass destruction.

He said the United States sent a mobile unit to Albania in 2006 to destroy that nation's 16-ton chemical stockpile at the request of Tirana.

"It took them about a year to do that," said Mauroni. "So if Syria has 1,000 tons, you can see that it probably cannot be done within a year."

Syria's two-year civil war also could make it hard for any foreign personnel and equipment to operate in the country.

In an interview broadcast Monday, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad told China's CCTV network that rebels fighting to overthrow him could stop foreign teams from reaching government-run chemical sites.

American University international relations professor Sharon Weiner said blocked access would not be the only risk.

"I could imagine that each of the partisans in that civil war would have a different take on whether or not you target or protect the people trying to destroy these weapons," Weiner said. "So those people would get caught up in that larger conflict."

Destroying the Stockpiles Overseas

To avoid such problems, world powers could send Syria's chemical weapons to facilities in the United States and Russia for quicker and safer handling.

The United States has two facilities where it plans to dispose of its remaining munitions in the coming years. One is undergoing testing in Colorado, while the other is under construction in Kentucky.

Russia is destroying its remaining stockpile at four facilities in the regions of Bryansk, Kirov, Kurgan and Penza. Construction of a fifth complex in the Kizner region is nearing completion.

But the option of using those facilities also presents dilemmas. Neither Washington nor Moscow has confirmed whether it would agree to bring Syrian stockpiles into its territory.

Challenges to the Overseas Option

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) also prohibits the "transfer, directly or indirectly, of chemical weapons to anyone." Mauroni said OPCW would have to make an exception to its rules to allow such weapons to be taken out of Syria.

Transporting the chemical munitions would be another challenge. Mauroni said he doubts anyone would want to fly with such hazardous cargo, making ground vehicles a more likely mode of transport.

Map of Chemical Weapons Destruction Facilities

The U.S. military used that method before. In 1990, it packed up a U.S. chemical stockpile near Clausen, Germany, put the munitions onto trucks and drove them to the German port of Nordenham.

From there, the U.S. military shipped the munitions to Johnston Atoll in the Pacific, where they were destroyed. The CWC ban on transferring such munitions had not yet taken effect.

"So, is it safe to take them by road? Absolutely," Mauroni said. "Transporting them by ocean, as long as there are no storms, also is not a problem."

Cost and Verification Issues

If world powers can agree on where to destroy Syria's chemical weapons, they still face uncertainties in how to pay for and verify the process.

President Assad has said he believes it would cost $1 billion. Weiner said it is too early to be sure.

"The cost depends on factors like how far you have to transport the weapons and how much you have to pay to protect the people who are destroying them," she said. "Anyone who tries to give a realistic estimation right now just doesn't have the information they need to do that."

In order to verify the complete removal of Syria's stockpiles, OPCW needs to be sure the Assad government truthfully declared what it had. Any OPCW member that suspects Syria is hiding something can order a "challenge inspection" that Syrian authorities would have no right to refuse.

Weiner said the United States and Russia also would have to overcome their suspicions of each other.

"I can imagine the Americans wanting to be present to watch the disposal in Russia and vice versa," she said. "The Americans and Russians have a history from the Cold War of always wanting to know what each other was doing. So there is a lack of trust there."

Earlier this month, Washington and Moscow agreed that Syria's estimated 1,000 tons of chemical munitions should be destroyed or removed by the middle of next year. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad pledged to cooperate.

Under the plan, inspectors from the Netherlands-based Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons would be deployed in Syria by November to supervise the process. But world powers have not agreed or disclosed how it would unfold from there.

Doing the Job in Syria

If those powers decide to destroy the stockpiles within Syria, the process likely would involve sending in specialized mobile units. Building a permanent facility to do that could take a year or more, dragging beyond the mid-2014 date by which the stockpiles are meant to be gone.

The United States and Russia could provide the necessary equipment. Both powers have more than a decade of experience in destroying their own chemical stockpiles. But neither has said if it would join a Syria-based operation.

The United States has two types of mobile units for destroying chemical weapons - an Explosive Destruction System (EDS) that neutralizes munitions containing chemical agents, and a Field Deployable Hydrolysis System (FDHS) that neutralizes the chemical agents and their precursors in bulk.

The U.S. military has built five EDS units capable of handling several munitions at a time. It also unveiled its first FDHS unit in June, saying the system is "designed for worldwide deployment with operational capability within 10 days of arriving on site."

Problems with the Syria Option

U.S. counterproliferation analyst Al Mauroni told VOA that using U.S. Army EDS units to destroy munitions inside Syria would be slow.

"I don't think they could complete it within six months," he said.

Mauroni is director of the Alabama-based U.S. Air Force Counterproliferation Center, which educates Air Force leaders about how to deal with weapons of mass destruction.

He said the United States sent a mobile unit to Albania in 2006 to destroy that nation's 16-ton chemical stockpile at the request of Tirana.

"It took them about a year to do that," said Mauroni. "So if Syria has 1,000 tons, you can see that it probably cannot be done within a year."

Syria's two-year civil war also could make it hard for any foreign personnel and equipment to operate in the country.

In an interview broadcast Monday, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad told China's CCTV network that rebels fighting to overthrow him could stop foreign teams from reaching government-run chemical sites.

American University international relations professor Sharon Weiner said blocked access would not be the only risk.

"I could imagine that each of the partisans in that civil war would have a different take on whether or not you target or protect the people trying to destroy these weapons," Weiner said. "So those people would get caught up in that larger conflict."

Destroying the Stockpiles Overseas

To avoid such problems, world powers could send Syria's chemical weapons to facilities in the United States and Russia for quicker and safer handling.

The United States has two facilities where it plans to dispose of its remaining munitions in the coming years. One is undergoing testing in Colorado, while the other is under construction in Kentucky.

Russia is destroying its remaining stockpile at four facilities in the regions of Bryansk, Kirov, Kurgan and Penza. Construction of a fifth complex in the Kizner region is nearing completion.

But the option of using those facilities also presents dilemmas. Neither Washington nor Moscow has confirmed whether it would agree to bring Syrian stockpiles into its territory.

Challenges to the Overseas Option

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) also prohibits the "transfer, directly or indirectly, of chemical weapons to anyone." Mauroni said OPCW would have to make an exception to its rules to allow such weapons to be taken out of Syria.

Transporting the chemical munitions would be another challenge. Mauroni said he doubts anyone would want to fly with such hazardous cargo, making ground vehicles a more likely mode of transport.

Map of Chemical Weapons Destruction Facilities

The U.S. military used that method before. In 1990, it packed up a U.S. chemical stockpile near Clausen, Germany, put the munitions onto trucks and drove them to the German port of Nordenham.

From there, the U.S. military shipped the munitions to Johnston Atoll in the Pacific, where they were destroyed. The CWC ban on transferring such munitions had not yet taken effect.

"So, is it safe to take them by road? Absolutely," Mauroni said. "Transporting them by ocean, as long as there are no storms, also is not a problem."

Cost and Verification Issues

If world powers can agree on where to destroy Syria's chemical weapons, they still face uncertainties in how to pay for and verify the process.

President Assad has said he believes it would cost $1 billion. Weiner said it is too early to be sure.

"The cost depends on factors like how far you have to transport the weapons and how much you have to pay to protect the people who are destroying them," she said. "Anyone who tries to give a realistic estimation right now just doesn't have the information they need to do that."

In order to verify the complete removal of Syria's stockpiles, OPCW needs to be sure the Assad government truthfully declared what it had. Any OPCW member that suspects Syria is hiding something can order a "challenge inspection" that Syrian authorities would have no right to refuse.

Weiner said the United States and Russia also would have to overcome their suspicions of each other.

"I can imagine the Americans wanting to be present to watch the disposal in Russia and vice versa," she said. "The Americans and Russians have a history from the Cold War of always wanting to know what each other was doing. So there is a lack of trust there."