WASHINGTON —

President Barack Obama is holding off on a decision to attack Syria so he can explore a negotiated settlement on securing and destroying the country’s arsenal of chemical weapons.

Twice in recent years - in Iraq and in Libya - the U.S. and its allies have dismantled and destroyed chemical weapons programs, but never in the middle of a war.

But Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association, says the experience gained in Iraq and Libya shows that dismantling Syria’s chemical weapons program is feasible, even during armed conflict.

“However, the situation in Syria is different in some ways,” Kimball said. “It’s going to be more challenging to survey these sites, secure these sites, verify the Syrian government’s declaration about stockpiles, the volume, the types, the locations.”

But if the inspectors—either from the Organization for Prohibition of Chemical Weapons [OPCW] or named by the U.N.—have access to personnel and records, they can do their job well enough to secure these stockpiles and deny the Assad government access, he said.

And that would insure, according to Kimball, that “after the hostilities end, these very dangerous stockpiles don’t fall into other dangerous hands.”

So assuming Syria offers the access it has promised, then what?

First, the Assad government would need to sign the 1992 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), the arms control agreement that prohibits the production, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons. Within two or three weeks after that, Syria would need to fully declare its chemical weapons inventory.

“And then they need to immediately allow inspectors from the OPCW or the U.N. team led by Dr. [Ake] Sellström to inspect the facilities,” Kimball said, “to verify the declaration, to make sure that it’s complete and accurate, and to secure the sites and effectively take control so that the chemical agents don’t leave the facilities, and the facilities are not compromised by outside threats.”

Kimball says these are the most important priorities.

“The task of verifiable destruction would be something to be conducted at a later stage, depending on the situation on the ground and the status of the conflict,” he said.

Chemical weapons are difficult to dispose of - they either have to be incinerated or neutralized with other chemical agents. That takes time, and it also takes special facilities.

Destroying Chemical Agents

Decades ago, the United States and Russia destroyed its chemical weapons by burying them, burning them in open-air pits, or dumping them in the ocean. Because of the obvious risk to human health and the environment, the CWC put an end to these practices in 1992. These days the United States and Russia destroy chemical weapons either by burning them at high temperatures or by neutralizing them with water and other agents.

Liquid chemical agents are burned in a furnace at a temperature of roughtly 1,100 C, about as hot as molten lava. At that temperature, the actual burning of the chemical agent would take only seconds.

Chemicals contained in bombs or artillery shells are disassembled by robots, and the liquid chemical agent is drained and sent to be incinerated. Meanwhile, metal parts are fed into a separate furnace and melted. This ensures that any residual chemicals are also destroyed.

Some toxic chemicals such as mustard gas can be destroyed by neutralizing them with either hot water or a combination of hot water and sodium hydroxide—a process known as hydrolysis. This process gives off a byproduct, hydrolysate, which is then treated separately.

Both methods would require the construction of an additional facility near the storage sites or at some central location for the incineration or the neutralization of the chemical agents.

“These facilities don’t exist in Syria today,” Kimball said.

It is a costly proposition. As a general rule, it costs 10 times more to destroy chemical weapons than to produce them. According to one 1996 assessment, the cost of dismantling, storing and destroying U.S. chemical weapons was $11-15 billion.

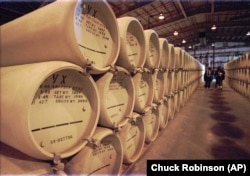

Environmental clean-up would run another $15-20 billion. U.S. stockpiles of mustard gas, VX and Sarin were stored at only a few facilities, but Syria has weapons stored at an estimated 40 locations across the country.

Doing the math, it could take years to destroy what has been billed as the third largest chemical weapons arsenal after Russia and the United States – and America has been at it for more than 15 years.

Ensuring Inspectors’ Safety

It has been suggested by some experts that it would be impossible to guarantee the safety of a weapons inspection and disposal team while fighting is underway in Syria, but Kimball disagrees.

“Syria’s chemical arsenals are probably the most secure areas within the government-controlled territory today because these are their most valuable and sensitive military assets,” Kimball said, “and so the Syrian government can most likely ensure the basic safety of the inspection teams looking at these facilities.”

That said, there are still too many unknowns to put an exact timetable on the process, says Kimball. And there is still no guarantee that the Syrian government will really be willing to comply with the exacting demands that would be placed on it by the international community.

Twice in recent years - in Iraq and in Libya - the U.S. and its allies have dismantled and destroyed chemical weapons programs, but never in the middle of a war.

But Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association, says the experience gained in Iraq and Libya shows that dismantling Syria’s chemical weapons program is feasible, even during armed conflict.

“However, the situation in Syria is different in some ways,” Kimball said. “It’s going to be more challenging to survey these sites, secure these sites, verify the Syrian government’s declaration about stockpiles, the volume, the types, the locations.”

But if the inspectors—either from the Organization for Prohibition of Chemical Weapons [OPCW] or named by the U.N.—have access to personnel and records, they can do their job well enough to secure these stockpiles and deny the Assad government access, he said.

And that would insure, according to Kimball, that “after the hostilities end, these very dangerous stockpiles don’t fall into other dangerous hands.”

So assuming Syria offers the access it has promised, then what?

First, the Assad government would need to sign the 1992 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), the arms control agreement that prohibits the production, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons. Within two or three weeks after that, Syria would need to fully declare its chemical weapons inventory.

“And then they need to immediately allow inspectors from the OPCW or the U.N. team led by Dr. [Ake] Sellström to inspect the facilities,” Kimball said, “to verify the declaration, to make sure that it’s complete and accurate, and to secure the sites and effectively take control so that the chemical agents don’t leave the facilities, and the facilities are not compromised by outside threats.”

Kimball says these are the most important priorities.

“The task of verifiable destruction would be something to be conducted at a later stage, depending on the situation on the ground and the status of the conflict,” he said.

Chemical weapons are difficult to dispose of - they either have to be incinerated or neutralized with other chemical agents. That takes time, and it also takes special facilities.

Destroying Chemical Agents

Decades ago, the United States and Russia destroyed its chemical weapons by burying them, burning them in open-air pits, or dumping them in the ocean. Because of the obvious risk to human health and the environment, the CWC put an end to these practices in 1992. These days the United States and Russia destroy chemical weapons either by burning them at high temperatures or by neutralizing them with water and other agents.

Liquid chemical agents are burned in a furnace at a temperature of roughtly 1,100 C, about as hot as molten lava. At that temperature, the actual burning of the chemical agent would take only seconds.

Chemicals contained in bombs or artillery shells are disassembled by robots, and the liquid chemical agent is drained and sent to be incinerated. Meanwhile, metal parts are fed into a separate furnace and melted. This ensures that any residual chemicals are also destroyed.

Some toxic chemicals such as mustard gas can be destroyed by neutralizing them with either hot water or a combination of hot water and sodium hydroxide—a process known as hydrolysis. This process gives off a byproduct, hydrolysate, which is then treated separately.

Both methods would require the construction of an additional facility near the storage sites or at some central location for the incineration or the neutralization of the chemical agents.

“These facilities don’t exist in Syria today,” Kimball said.

It is a costly proposition. As a general rule, it costs 10 times more to destroy chemical weapons than to produce them. According to one 1996 assessment, the cost of dismantling, storing and destroying U.S. chemical weapons was $11-15 billion.

Environmental clean-up would run another $15-20 billion. U.S. stockpiles of mustard gas, VX and Sarin were stored at only a few facilities, but Syria has weapons stored at an estimated 40 locations across the country.

Doing the math, it could take years to destroy what has been billed as the third largest chemical weapons arsenal after Russia and the United States – and America has been at it for more than 15 years.

Ensuring Inspectors’ Safety

It has been suggested by some experts that it would be impossible to guarantee the safety of a weapons inspection and disposal team while fighting is underway in Syria, but Kimball disagrees.

“Syria’s chemical arsenals are probably the most secure areas within the government-controlled territory today because these are their most valuable and sensitive military assets,” Kimball said, “and so the Syrian government can most likely ensure the basic safety of the inspection teams looking at these facilities.”

That said, there are still too many unknowns to put an exact timetable on the process, says Kimball. And there is still no guarantee that the Syrian government will really be willing to comply with the exacting demands that would be placed on it by the international community.