South Africa, with its vibrant, multimillion dollar tourism industry, is home to thousands of holiday resorts – offering everything from pristine beaches to bush teeming with wild animals. But only one tourist haven is managed by three brothers from Malawi, in an isolated village that seems lost in the past.

In the town of Kaapsche Hoop, in the craggy mountains of South Africa’s northeastern Mpumalanga province, Emton, Aaron and Harvest Kalimanjira are known as “The Blantyre Boys.”

And while that description conjures up an image of a ruthless street gang wandering the alleys of Malawi’s commercial capital, it’s with respect and affection that the Kalimanjira brothers are spoken of in their adoptive village.

“It’s not a difficult place to stay. It’s nice and quiet, everything’s fine, no problems.” Emton, the eldest of the trio, who are in their mid to late 20s, speaks from behind the bar in the restaurant he runs. Aaron adds, “It is wonderful being here and meeting people from all over the world. They are great people, but sometimes quite strange!”

There are, indeed, many unusual aspects to Kaapsche Hoop. It’s a silent, spooky place, often engulfed in thick fog from which a resident herd of wild horses emerges. They graze among old wood and tin houses that once belonged to gold miners in the 1800s. Even the town’s name is incongruous – Dutch, for “Cape Hope.” Yet South Africa’s coastal Cape region lies more than a thousand miles to the south.

History books say a few centuries ago, prospectors named the village “Kaapsche Hoop” for the area’s unusual rock formations and swirling mist that reminded them of the Cape.

Locals say the Kalimanjira brothers only add to the village’s peculiar aura. Kaapsche Hoop is one of the last places in South Africa where one would expect to find three Malawians – unless they were tourists. Foreign Africans usually settle in or nearby South Africa’s big cities. But Kaapsche Hoop is so small that its entire population is less than 100. It’s “literally in the middle of nowhere,” says Harvest Kalimanjira.

The pull of the South African rand

Three years ago, after a bus journey of almost two days that took them from Malawi through Mozambique, Zimbabwe and finally into South Africa, the brothers arrived at Kaapsche Hoop. They’d been alerted by a fellow Malawian working nearby about probable job openings in the town.

“Because of our friend’s good work, the owners of this place wanted other Malawians to work here,” Emton says. In Blantyre, he’d been struggling to make ends meet as a heavy-duty truck driver. “The Malawi kwacha is worth almost nothing,” he explains, shaking his head.

“The amount of money that I get from this side is 20 times the money I get from Malawi,” adds Harvest, who has an interesting theory about why his parents gave him his rather “unusual” first name. “I think I was born in a time when they harvested a lot of maize (near my home village),” he says, smiling.

Aaron Kalimanjira says South Africa – and specifically Kaapsche Hoop – is “beautiful,” but he and his brothers are really here “for the money. With money we send our families in just one month, they are able to live in Malawi for about five months, because basic foods are much cheaper there.”

‘King Aaron’

Popping the cap off yet another beer for a thirsty patron, Emton exclaims, “We do everything here! I’m a barman, but I’m doing everything here – painting stuff or gardening, everything. Driving also. Chopping wood! All (that) stuff; we don’t have a choice!”

Inside their restaurant, the ears of customers are more often than not assailed by the Kalimanjira trio’s favorite music – reggae. “As loud as possible!” Harvest shouts, above the din from an overhead speaker.

“While one of us is playing music, the other is cooking, the other is serving drinks. Then the other must stand by the door, when we have the nightclub nights on weekends – lots of tourists,” Emton says.

When darkness descends on Kaapsche Hoop, the mellow reggae ends, and the “heavier, pumping stuff,” as Aaron describes it, begins. The blasting music causes the bottles behind the bar to rattle and shake, just like the people on the dance floor.

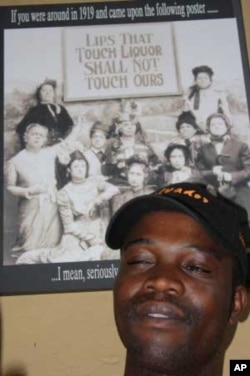

While the party rocks, the brawny Aaron Kalimanjira – muscular arms crossed over his chest and a mean glint in his eyes – mans the entrance. He jokes, “Any trouble here and it’s pow, pow!” He punches the air with a violent right-left combination. The skull of a dead animal nailed to the door looms over his head.

Aaron says he “hates” being a bouncer. “But when things get out of hand, like when a fight breaks out or when the visitors are very drunk, then I must do something to stop the trouble.”

Harvest adds, “That’s how he got his nickname, ‘King Aaron.’”

The Queen of England’s train carriage

Aaron, though, insists he’s more into “public relations” than maintaining public order. He says, “I’ve met with lots of kinds of people – other people from Canada, other people from India, other people from everywhere! To me that’s a very, very important thing because then I learn more things than before.”

But Aaron’s “best” job is to cook, and he especially enjoys making “a whole lot of different pizzas, burgers, pancakes – everything in the kitchen, I make it!” he laughs.

Another of the Kalimanjira brothers’ tasks at Kaapsche Hoop is to maintain an extraordinary train coach as accommodation for tourists. It’s the original carriage that England’s Queen Elizabeth II traveled in on her visit to South Africa in 1947.

“It’s got the same bed, the same carpets,” says Emton.

The Kalimanjiras miss their families.

Despite the Kalimanjira’s good work at Kaapsche Hoop, Harvest says he doesn’t like staying in South Africa. Whenever he phones home, he says, it seems as if a “new tragedy” has happened.

“And then I think to myself, ‘Maybe if I had been at home this bad thing would not have happened….’”

Harvest says he “bitterly misses” his wife, Sarah, five-year-old daughter, Sharon, and six-month-old son, Paul.

Emton says while he and his brothers have “good times” at Kaapsche Hoop, it’s “desperation” that drives their stay in South Africa, and again he repeats that there’s “no money to be made” back in Blantyre.

The cost of being economic refugees is etched on the brothers’ faces, and in the regrets they frequently voice.

“I’ve got a little daughter,” Emton says. “Her name is Praise. She’s now almost a year old. And I have never seen her.”

He says he “feels shame” because of this, and it’s a feeling that “never goes away” – no matter how much money he earns in South Africa.

Aaron says he, too, misses his daughter. “She’s two. Her name is Queen.” He laughs when he’s reminded that his nickname is “King Aaron….”

But work the Kalimanjiras must, adding unexpected cheer and diversity to one of South Africa’s more unusual tourist traps.