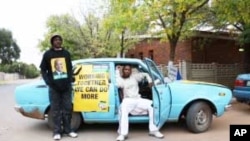

A ramshackle car with a mud-spattered body shutters along a dusty street leading into the small town of Petrusburg, in South Africa’s arid western Free State region. The car – its rusted exhaust sending acrid black smoke into the air – is driven by Pitso Marumo, an official from the local branch of the ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC).

Marumo is on the prowl for supporters to attend a party meeting. He brings his vehicle to a sudden halt in the middle of the road. His passenger and ANC colleague, Maboza Ledaka, leans out of the window and asks a woman, “Sister, will you be at our meeting later today?”

His clothing leaves his target in no doubt as to the politics behind the gathering. He’s wearing a black t-shirt depicting a smiling President Jacob Zuma. “I’ve hardly taken this shirt off since Msholozi won the election (in April 2009)!” he exclaims, using the president’s Zulu clan name.

In the hot and dry western Free State, towns slumber among vast golden maize and yellow sunflower plantations. It’s as if the elections that saw the rise to power of the controversial Mr. Zuma have yet to happen. “Stop Zuma!” proclaims a poster of the opposition Democratic Alliance.

“Too late!” Marumo says, laughing at the banner and shouting, “It’s too late to stop Msholozi! He will be our president for life; that is what I want!”

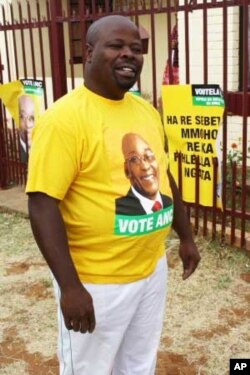

Although official campaigning ended with the 2009 polls, it’s still going on in some towns in Free State. People continue to walk the streets wearing buttercup yellow t-shirts encouraging fellow South Africans to “Vote ANC.” Ledaka says, “You still see these election things around here, because that election was the biggest thing ever to hit this forgotten part of the world. People don’t want to forget it; they want to keep it alive….”

Marumo says many issues that were raised during that election are still issues today – especially whether activists can campaign on private farms without permission: “As politicos, we have no choice but to continue addressing these issues until they are resolved.”

‘Politics doesn’t make food…. Only hot air’

In western Free State in particular, political rivalries born during the election are still simmering as a result of some white farmers who allegedly refused – and are still refusing – to allow their laborers to be involved in political activity. Marumo says the farmers threaten to fire any workers who disobey them and refuse to allow political meetings on their land. The farmers say politics interferes with farm work and lowers their production, so it’s bad for South Africa’s economy.

During the 2009 election period, Marumo says, ANC agents were able to ensure that political rallies were held on farms in the largely rural region. “Most of our supporters here work on isolated farms; the only way to reach them is to go and speak about politics on the farms themselves,” he explains. But the ANC official adds that some farmers remain “stubborn,” which means the issue of political activity on farmland is “far from dead.”

He says “government intervention” is sometimes called for, in which case officials from the relevant state agency visit the farmers to “negotiate” access to their land. The officials visit farmers like 72-year-old Barend Reynecke, who’s listening to static-filled commentary on a rugby game on a small transistor radio on his stone porch. Despite the mind-numbing heat, Reynecke is clutching a mug of steaming coffee.

The rancher’s grimaces and groans offer proof that he’s in a bad mood. His team’s losing. To make matters worse – they’re losing to their bitter rivals. “Those big city fancy-pants from Johannesburg!” Reynecke says.

With a large, sunburned hand, he swats a fly away from his face and declares, “We farmers allow politics on our farms. But we have a rule that political meetings must not take place when there’s urgent work to be done. We have a responsibility to produce food for this country. Politics does not make food. It makes hot air.”

Reynecke’s floppy khaki sunhat, decorated with leopard-skin print material, almost falls off as he nods vigorously to the rhythm of his words. “Some workers and the ANC have a problem with rules and discipline. They would like to have a political rally on a farm every day. We can’t allow this.”

The farmers are ‘good people’

A few miles down the asphalt from Petrusburg is another similar town, Koffiefontein. In English, its name is ‘Coffee Fountain’ – the settlement that Afrikaners named centuries ago after a stream, its water the rich dark brown color of the brew. Huge silver grain silos loom over the place. A massive copper kettle – reinforcing Koffiefontein’s association with coffee – welcomes visitors at the entrance to the town.

Resident Storm Parker says the ANC and local farmers “can’t ever be friends” because, she says, “the ANC just arrives on the farms out of the blue and then expects everyone to just jump for them” – a charge Marumo denies, saying “all meetings are organized well ahead of time.”

Parker’s married to a farmer. She says men like her husband “personally” transport their workers into town to allow the laborers to attend ANC rallies and provide the workers with food to eat at such events. The issue, Parker maintains, is not the farm laborers’ support of a particular political party, but rather that “farmers believe politics must be kept off their farms…. But if the meetings are held elsewhere, that’s fine.”

On Koffiefontein’s main street, support for the farmers arrives from an unexpected source – in the form of ANC official Tshokolo Mantjies. He’s wearing a t-shirt – again depicting a grinning Jacob Zuma – and is sheltering from the sun under a tree, the wind chimes hanging from its branches blown gently by a breeze.

Mantjies says “as far as possible, politics must not interfere with farming…. Our country needs food, and farmers must be left to farm, not worry about political gatherings on their land.”

He adds, “From what I have seen in this province, many farmers even go so far as to help their workers to get involved in politics.” Mantjies describes what he witnessed at Koffiefontein on election day in 2009.

“I’ve seen three farmers with vans. And they had their farm workers on the vans and they brought them to the voting stations to come and vote,” he says. Mantjies says most white farmers in the western Free State are “good people” – even though “they don’t like” the ANC.... “But that is their right,” he stresses.

‘The number of the beast’

On a farm not too far from Mantjies’s homestead, opposition Congress of the People (Cope) supporter Azael Mashampi drives his tractor into a strong headwind. “Yes, we lost the election. Zuma won,” he sighs, switching the vehicle’s engine off and climbing down.

Mashampi’s more upbeat wife, Elisa, chips in, “But we weren’t destroyed. We’re still here. We now have people in parliament. At least we stopped the ANC from getting 66, 6% (of the vote, which would have given it a two-thirds majority in parliament).”

“And just as well for them!” Azael interjects. “In the Bible, 666 is the devil’s number, the number of the beast….”

Azael says he’s worked for farmers in the Free State for decades and – although there are some “bad types” among them – “they are the biggest providers of jobs in this province. As such, the good they do far outweighs the bad.”

Shielding his face from dust whipped up by a sudden gust, Azael says, “The farmers are with us. Many of them, they vote (for) Cope. So, we are standing together with the farmers. We’ve always said our arms are open for the farmers.”

Dogs, pigs and the egghead

Back at Petrusburg, Jan Tokkel puffs on a cigarette, his arms leaning on a steel fence. Sweat beads on the hairs of his moustache and beard. A homemade sign is mounted on the man’s front gate. Its crooked lettering is scrawled on a chunk of old school blackboard. The sign reads, ‘Hey. Be careful of the pig that’s going to eat you.’

Tokkel laughs uproariously when asked about it. “I am a small farmer – pigs,” he says, strings of white smoke curling out his flaring nostrils. “Did you know that pigs are the best guard dogs on this earth? Dogs are much more stupid than pigs,” he says.

Unlike many small town residents in western Free State, Tokkel says he doesn’t care at all about politics. “In fact, politics is banned on my farm – not that anyone would want to hold a blerrie (bloody) political rally here!” he says, raising his voice in mirth, and casting his eyes across a plot strewn with broken bricks and old car parts. At the back of the yard, some men slouch against a wall, gulping beer from large brown bottles.

A woman pokes her head around a corner, squinting into the sunlight. Addressing the men, she asks, ““What’s going on here?” A man tells her, his voice slurring, “Someone from the American newspaper is here to talk about Zuma.”

Oh! The eierkop (egghead),” she says, using another term of affection for the president – this time referring to Zuma’s large, shiny pate. The drinking men cackle into their beer bottles.

“By the way,” she says, clutching a bundle of dirty washing and simultaneously arranging multicolored curlers in her bush of disheveled hair, “How is he doing? Is he going to do something good for the Free State?” she asks, dipping into the bucket holding a pile of underclothes and arranging one of the garments on a line.

“I don’t know,” answers another man, beer froth lining the sides of his mouth. “Ask the man from the newspaper,” he tells the woman, rolling his calcified eyes.

“Who cares, says Tokkels. “Life is still the same here, nothing’s changed. Zuma must give me money so I can feed my pigs properly. If he does that, then maybe I will also join all you nikswerde (good-for-nothings) who do nothing all day except talk kak (nonsense) about politics.”

Then Tokkels ambles off, his slippers shuffling in the dust. “My pigs are hungry,” he repeats.

The washer woman stares after him. “Everything here is hungry,” she says to Tokkel’s back.

“But not thirsty!” says the man with the dead eyes, smiling as he sucks at the neck of yet another bottle.