Fred Van Der Merwe remembers creeping through the red dust, “wide-eyed with fear” and rifle at hand, a young boy ready to “kill and die” to protect his family’s farm north of Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare. It was the mid-1970s, and civil war was raging between the troops of the white minority Rhodesian government and the black liberation forces, led by Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo.

“I can’t say I ever remember my parents talking about politics,” Van Der Merwe says. “Our carrying weapons on the farm was only geared towards protecting our land from whoever attacked it.”

But the family’s dream of “forever” farming in a democratic Zimbabwe ended in 2001, when Mr. Mugabe’s war veterans seized their land by force.

“From a very early age, I guess my life was defined by conflict,” Van Der Merwe reflects. “But everything changes,” he adds.

Indeed, the Fred Van Der Merwe of today describes himself as a “changed man – forced by circumstance” to transform himself from a successful tobacco, maize and cattle farmer into a master beer maker – albeit as an “exile” in South Africa.

He acknowledges his path to business here has been “a sometimes traumatic” metamorphosis…but one that’s bringing pleasure to the many beer lovers from across the globe who visit his brewery on top of the precipitous Long Tom Pass in South Africa’s mountainous Mpumalanga province.

‘Whisky water’ is the secret

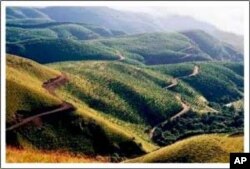

Rolling green hills and ghostly mist add to the mysterious atmosphere of Van Der Merwe’s distillery, which – at an altitude of almost 2,200 meters – is the highest brewery in Africa and one of the highest in the world. “Drinking our beer in such thin air gives it a very unique taste,” the brewer comments, while standing among huge stainless steel boilers that hum and hiss as water, malt, barley and hops ferment into beer.

“It’s not the type of thing that you can brew from your house or your garage. It’s complicated,” Van Der Merwe says.

His ingredients are steamed in “mash tanks” and then pumped into big copper kettles, where it’s stored for a few hours “to get the concentration right.” Then, it’s channeled into tanks, where yeast is added. The blend is allowed to ferment for a week, after which the beer has its required “kick” – namely a healthy percentage of alcohol. The brew’s then pumped into “conditioning tanks,” where gas is added. Van Der Merwe’s beer is now ready to be put into kegs to be served from the tap to thirsty customers or bottled for transport elsewhere.

“Altogether it’s a very expensive process,” he says. To maintain consistency of flavor, the brewer spends many thousands of dollars every year on malt, barley and hops bought from the same local and European sources.

“If we import from a certain place in Germany or the United Kingdom, it’s got to come from there all the time,” he tells VOA. “We can’t buy hops of a certain type from Russia, for example, and then buy the next batch from the UK, because of the climate differences (in these different places) that change the quality (and taste) of a product.”

But it is “simple H2O,” maintains Van Der Merwe, that’s the most important additive in high quality beer. “Water makes a good brew, not costly foreign-sourced grains,” he says. “They are secondary.” Van Der Merwe uses water from a natural spring on his property. “The water is pure, it’s clean and it has a taste all of its own. It still contains all the minerals; none of that gets filtered out,” he says.

The spring’s called the Whisky Spruit (Creek). It was named centuries ago by pioneers to South Africa’s interior who camped at the stream and mixed its cool water with their fiery whisky.

The ‘big gun’ of the beer world

The location of Van Der Merwe’s brewery, on one of the many steep, hairpin bends that characterize the Long Tom Pass, ensures that his link with conflict hasn’t yet been severed, for his business is at the scene of one of the most famous battles in South African military history. For five days in 1900, as the Anglo-Boer War between British forces and Afrikaner Boers reached its zenith, Boer General Louis Botha – with only 3,500 men and three “Long Tom” cannons – repulsed 30,000 British troops armed with 88 extreme-range howitzers, before finally being defeated.

The Long Tom Pass is named after one of Botha’s famous guns, preserved at a monument near Van Der Merwe’s homestead, which now shelters not soldiers, but thirsty beer connoisseurs.

“We basically brew four different kinds of beer,” he explains.

Van Der Merwe’s Blacksmith’s Brew is “very light, and tart, and naturally cloudy, based on the centuries-old tradition of Belgian white beer, or witbier.”

His signature Digger’s draught beer is based on Kölschbier, which originated in the German town of Köln in 1254. Van Der Merwe says it's "light in body and flavor; quite fruity” – the result of the South African pale malt and imported German winter wheat malt used to make this beer.

Van Der Merwe describes his Mac’s Porter brew as an “old English style” beer, with a “malty, creamy fullness, smooth as silk, with chocolate and coffee undertones and a deep ruby color.” Then, plopping a mug of thick, golden liquid on the mahogany bar counter, he presents what he calls his “big gun,” a mischievous smile creasing his tanned face.

“The Old Bull Bitter is based on a British ale type of beer. It’s high in alcohol – not for sissies,” Van Der Merwe says. “It’s spicy; lots of aromatic floral flavors” – the result of what the brewer calls the “late addition of unprocessed Styrian Goldings leaf hops” imported from Britain.

African microbrew explosion

Van Der Merwe is what’s become known around the world as a “microbrewer” – a rarity in Africa, where the beer industry is dominated by immense corporations that mass-produce the continent’s most popular alcoholic beverage. He’s at the vanguard of what he hopes in the future will result in increasing numbers of Africans turning away from “bland factory beer” and towards “microbrews,” made with “absolutely no enhancers or unnatural additives being used anywhere in the brewing process.”

Van Der Merwe, however, acknowledges that his quest may remain unfulfilled.

“Brewing beers on such a small scale is virtually unknown in Africa. Africans remain very loyal to the commercial, mass-produced beers and many aren’t willing to experiment with others.

"So at the moment, our local, home-grown and produced beer is very much for a niche market – these are people with a bit of money to spend on indulging in fine beer; they are like wine lovers of the beer world, so to speak.”

The Zimbabwean doesn’t hesitate to equate the consumption of microbrew beer with that of fine wines. “Just as a great Shiraz goes excellently with a steak, so too can a unique microbrew. Just as a wine snob will swirl wine in his mouth and comment, ‘Very fruity, with hints of vanilla,’ so too will an appreciator of a microbrew beer swirl the beer in his mouth and comment, ‘Ah! A coriander flavor….’”

Substandard beer

But at the moment, says Van Der Merwe, African microbrewers are “somewhat isolated.”

“We’re all small guys; we thrive because of word of mouth, not big, multimillion rand advertising campaigns…. So it’s going to take time for us to establish ourselves.” He adds that some South African microbrewers “haven’t exactly helped the cause” by producing beer that’s “not up to scratch.”

“(African) microbreweries still need to achieve a standard as far as the quality of the beer is concerned,” Van Der Merwe says. “The more established microbreweries do keep a reasonably high standard. However, there are many microbrewers still in a very early stage as far as the perfection of their beer is concerned.”

The quality of beer from these manufacturers, he says, “fluctuates too much. They might have had a batch of beer that tasted fine; the following batch tasted different. That sort of fluctuation puts people off.”

As Van Der Merwe reflects on his journey from farmer “under siege” in Zimbabwe to premier beer brewer in South Africa’s beautiful Mpumalanga highlands, he sips at another of his creations and says softly, “South Africa’s been good to me….”

And now, he’s passing some of that goodness on to his customers, in the form of some of Africa’s most extraordinary beer.