Bring up the subject of Native Americans to any group of Americans, and at least one person will claim to have a Cherokee ancestor, pointing to high cheekbones or straight dark hair as evidence. Chances are, there’s not a single Indian in his or her family tree.

Dubbed the “Cherokee Syndrome,” it is a growing trend in America: More than 819,000 Americans self-identified as Cherokee on the 2010 federal census, alone or mixed-race. By comparison, the combined population of the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes — the Cherokee Nation and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee in Oklahoma, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee in North Carolina — amounts to fewer than 400,000.

Some of those checking the “American Indian” box on census forms may indeed have Cherokee ancestors, but a significant number do not. Even so, they are “going Native” in increasing numbers. Furthermore, they are connecting with one another on social media to form groups.

“It’s really not that big of a deal for people to come together and discuss their common beliefs and history,” said David Cornsilk, historian and genealogist, and citizen of the Cherokee Nation and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee. “But then they start calling themselves ‘tribes.’”

More than 200 unrecognized tribes that claim to be Cherokee exist across the country, some of them selling fraudulent tribal ID cards, representing “Native culture” to non-Natives, and selling counterfeit “Native art.”

“To give themselves ‘Indian’ cache, they appoint ‘chiefs’ and give themselves outrageously ridiculous Indian names,” said Cornsilk. “For recognized Cherokee, we don’t use names like this. Our Cherokee names are kept private.”

The advent of do-it-yourself DNA test kits has made things worse, said Cornsilk. The tests are unreliable and can’t prove genetic affiliation with individual tribes. Even if they could, they would not satisfy criteria for tribal citizenship, which demands direct descendancy from individuals listed in historic government “Indian rolls.”

‘The trail where they cried’

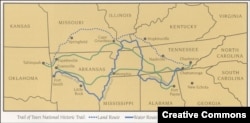

The original Cherokee homeland stretched across all or portions of eight present-day southern states. By the 1820s, they had ceded 75 percent of this land to the U.S. government.

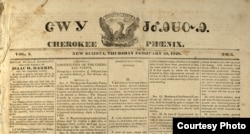

By this time, the Cherokee had developed extensive cultural and economic ties with white culture, developed their own written language and a republican government, which its leaders hoped might help discourage further cessions of land or their removal altogether.

But after gold was discovered in Georgia, the federal government convinced a renegade faction of Cherokee to sign a treaty ceding all their remaining land. And in 1838, the first of 16,000 Cherokees began the 1,000-mile journey along what the Cherokee remember as Nunna daul Isunyi, “the trail where they cried.” At least 4,000 died along the way.

Some 800 Cherokee managed to avoid removal. Their descendants constitute the Eastern Band of Cherokee, today headquartered in western North Carolina.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, white Georgians in particular felt they were under siege by the North, said Virginia Commonwealth University historian Gregory D. Smithers, and began to romanticize the Cherokees’ plight at the hands of the northern government.

Historians believe this marked the beginning of Cherokee syndrome.

“By either appropriating a Cherokee identity or drawing parallels between Cherokee removal and their own struggle to preserve and extend the slave system, white Georgians constructed a false equivalence to justify their pro-slavery politics,” Smithers said, adding that those who did fabricate Indian heritage “chose a ‘relative’ who was distant enough to ensure their white privilege wasn't tarnished.”

In the early 1900s, the U.S. government agreed to compensate the Eastern Cherokee for lands it had earlier seized. Encouraged by lawyers, fake Cherokees began popping up across the country, hoping for a share of the windfall.

Eventually these false claims wove their way into family legends, many of which are firmly fixed today. A growing number of individuals are either joining up with fake tribes or applying for citizenship in federally recognized Cherokee tribes.

Filling voids

Many assume that Cherokee “wannabes” are looking to cash in on government benefits, casino earnings, educational scholarships or added cache as academics. But Cornsilk believes the explanation isn’t so simple.

“They feel lost. I think Gloria Steinem probably said it best when she described white Americans as ‘a people without a tribe,’” he said. “They hunger for it. But rather than going back and finding their own tribe — Ireland, England, France or Germany — they want a connection to this continent.”

And they choose Cherokee identity, he added, because the Cherokee are historically emblematic of the so-called ‘civilized’ Indian.

Circe Sturm, University of Texas anthropologist and author of “Becoming Indian: The Struggle over Cherokee Identity,” suggested another reason:

“I believe that there is a retreat from white guilt that is happening here,” she said. “Whiteness is responsible for indigenous dispossession and the lack of societal connection that characterizes modernity.”

Today, federally recognized Cherokee tribes have taken a public stand against these individuals and phony tribes.

“They undermine the authority of the Cherokee people themselves to say who is and who is not a part of our community,” said Cornsilk. “It is utterly dismissive of the sovereignty and status of the Cherokee Nation, the United Keetoowah Band and the Eastern band of Cherokee.”