WASHINGTON DC — Chhang Song, a wartime information minister, post-war ruling party senator, and self-styled ambassador of the Cambodian-American community, was born a writer. As a child of poor parents in rural Takeo province, he made chalk out of clay and used it to write the alphabet on crude slate. Later, he used sharpened bamboo to carve banana trees.

“On these trunks, I wrote stories for villagers to read the next day when the trunks became dried and the writing showed up,” he wrote decades later on Facebook, his preferred medium in his later years.

He could write in three languages: Khmer, English and French. He kept writing even after the first round of obituaries were written about him in May 2021: it turns out he was still “clinging to this world on life-support,” his wife informed news agencies after the false alarm, and he would eventually wake up from a coma.

“I've often shared publicly what is on my mind,” he wrote in a series of posts about his near-death experience. “For this reason, some people may think my head must be now empty. Au contraire, my friends, I am loaded with what I wish to share with you all.”

Writing was Chhang Song’s compulsion, his therapy. As his body started to fail him earlier this year, so too did his computer for a time. When he was able to type again in Khmer, he wrote, “I feel liberated and the stress seems to fade away.”

Chhang Song did finally pass away on Aug. 21 at the age of 84. Recently passed was the 100-day mark of his death, when he moved onto his new life, according to Buddhist beliefs.

He was a unique political figure in modern Cambodia, fiercely loyal to Lon Nol, president of the US-backed Khmer Republic in the 1970s, and then hitching his wagon to the Vietnam-installed Cambodian People’s Party in the 1990s. He left behind vivid pictures of both eras, with a front-row seat to Cambodia’s descent into war, the global diplomacy that eventually brokered peace, and the troubled experiment with democracy that followed.

He shared his stories through Facebook posts, newspaper articles, research papers, public forums, press briefings, online interviews — wherever he could get them out. Charismatic and always up for a chat or a meal, Chhang Song created connective tissue between eras and continents that remains strong even now that he is gone.

Chhang Song spent much of his boyhood studying at Buddhist temples in Takeo. He first moved to America as a student at Louisiana State University, part of a USAID scholarship program that trained him in agriculture development, and also sent him to work for a short time in Illinois. “I was undoubtedly the only Cambodian who was involved in the 1968 huge anti-war demonstration in Chicago,” he wrote.

He returned to Cambodia in 1969, while Prince Norodom Sihanouk was still in power. “Upon my return to Cambodia, Head of State Prince Sihanouk greeted me among a small group of students who had studied abroad and singled me out to work at his private cabinet as an editorial assistant,” he wrote.

Within a year, Sihanouk was deposed in a coup and replaced by his own military chief, Lon Nol, who inherited a brewing crisis with the war in Vietnam spilling over the border and U.S. President Richard Nixon conducting bombing campaigns against North Vietnamese bases inside Cambodia.

Chhang Song would be enlisted as a wartime briefer and liaison to foreign journalists, as fighting against North Vietnamese turned into an all-out civil war against the Khmer Rouge that increasingly pinned Lon Nol’s military into Phnom Penh.

Skip Isaacs, who was a Baltimore Sun war correspondent, noted Chhang Song’s “humor and good nature in a very depressing time.” Jim Laurie, another correspondent at the time, recalled his daily press briefings in Phnom Penh.

“At the front, Chhang Song with Colonel Am Rong provided their daily ritual of growing misery sprinkled with jokes about troops going to war in Pepsi Cola trucks. ‘If we had Coca Cola trucks, we would do better, because everyone knows things go better with Coke,’" Laurie wrote.

Laurie said Chhang Song was popular with the ladies as well.

“In 1970, he was really the player. He was considered, you know, the man to meet,” Laurie said in an interview. “There were always so many jokes about Chhang Song was on the make with every woman he could find.”

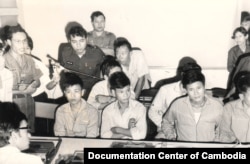

Youk Chhang, a cousin of Chhang Song who now runs the Documentation Center of Cambodia, remembers fetching beers and coconuts for journalists who would attend briefings at the family’s home in Tuol Kork. He recalls the journalists — tall, white, carrying cameras and speaking English and French — would listen intently as his cousin would “say something in English which I didn’t understand.”

One of those journalists was Kate Webb, a New Zealand-born journalist who headed UPI’s bureau in Phnom Penh. One day in 1971, she went to cover a battle between government forces and the Vietcong about a hundred miles outside Phnom Penh. She didn’t return that night or for several days after, causing her colleagues to become “frantic,” Chhang Song recalled in a Facebook post.

A subsequent search yielded a shocking result. It reported that KATE was killed during an attack against the government soldiers in Pich Nil pass. Her body was found among other 16 partially cremated bodies. The report of the first White female journalist killed in Cambodia's war with her body cremated on the side of the road spread all over the world and generated further discussion on the war.

Three weeks after KATE had disappeared, my office telephone rang and I picked it up. At the end of the line, a woman voice spoke softly: "Song, it's Kate. Pick me up at the military section of the airport."

Webb had been captured and eventually released by Vietnamese soldiers, subjecting her and a group of colleagues to forced marches, interrogations and malaria. She would write about the experience in the book, “On the Other Side.”

Within a few years, Chhang Song was appointed as the information minister. On April Fool’s Day, 1975, he joined the delegation with Lon Nol on a flight out of Cambodia.

Many accused the general of fleeing, while it was officially billed as a medical trip. Long Boret, then the prime minister, called it “un coup silencieux,” or a silent coup, “to deprive the enemy of using Lon Nol as the major obstacle to a negotiated settlement,” Chhang Song wrote in an article for The Cambodia Daily newspaper.

At the president’s palace that fateful morning, Chhang Song later wrote that he still held out hope that he would return home within a few months.

Soon Lon Nol walked out with his wife toward the waiting giant helicopter while saluting the people in the Khmer way, wiping tears off his eyes with a white handkerchief, while from the porch of his residence, people waved him goodbye. Some collapsed quietly sobbing.

It turned out Chhang Song would not return to his home country for more than a decade. As the Khmer Rouge began a bloody reign that would kill an estimated 1.7 million of his countrymen, Chhang Song found a temporary home in Hawaii, where he went to work on a Korean-owned lettuce farm for 75 cents an hour.

Like disowned dogs on an island, we suffered the unspeakable separation from our families while we knew that mass killings and murderous social cleansing policies were practiced by the victorious Khmer Rouge on the population of Cambodia. For months then for years, we had no news from our families.

Chhang Song met his first wife while in Hawaii. They moved to Virginia, where they would live for the next decade while raising three children. In 1977, he appeared at a press conference with Rep. Stephen Solarz (D-N.Y.) and told assembled reporters of the “holocaust” happening in his home country.

Maybe the term Holocaust was not so appropriate for killing of one third population of Cambodia; but I used such a term in 1977, two years after the fall of Cambodia to the Khmer Rouge, and it counted when no one else had thought of Genocide or of the Killing Fields.

Now close to Washington DC’s halls of power, Chhang Song started and ran a non-profit called Save Cambodia Inc., through which he organized cultural programs and sponsored hundreds of Cambodian families who moved to the U.S.

He also edited Cambodia Today, a magazine and platform for his political views. He lobbied Congress for laws to allow more Cambodians to settle in America, and spoke out against proposals to arm “anti-communist” factions as the civil war raged through the 1980s.

He flattered senators at hearings, and assured them that humanitarian support for Cambodia would pay dividends. “We know that the best way we can pay our debt to America is by using the lessons of democracy we have learned here to ensure that democracy is reestablished in Cambodia,” he said during a 1989 hearing.

Later that year, he decided to witness for himself the conditions under the government led by Hun Sen. He wrote about his trip in a report submitted to the U.S. Senate’s Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Asian Affairs.

Much of his trip was spent confronting what was lost. He visited his old office at a printing plant in Phnom Penh, where he spent "perhaps the most productive time of my life” as a press liaison for Prince Sihanouk and then Lon Nol. What he found was both heartwarming and heart shattering.

My old office was still there, locked. This was where I spent my evenings proofreading government releases, a variety of texts and books. Often, I would work all night long going over hundreds of cables. I was told that people had been saying to each other that one day I would return. Thus, they had kept the office locked until I did.

Of the 240 employees he had worked with at the plant, only six had survived the Khmer Rouge.

Later, he visited his hometown in Takeo, and described how the Khmer Rouge killed his 34-year-old brother not far from his family’s house, piecing together recollections from others.

He cried out for help from the villagers, from Buddha, from God, from our mother and from me. He succumbed while others hushed up in their huts, for fear of being the next victims.

"We missed (expletive)-Chhang Song, the dirty American dog," said the Khmer Rouge who knew our family well and who knew that I had a long connection with the Americans…

"But at least we've got one of his seeds, A-Phi, his young brother," the Khmer Rouge said to each other. "We'll exterminate this younger dog instead."

Chhang Song’s report to the Senate was mostly a plea for the U.S. to stay out of the civil war. He wanted America to know that Hun Sen’s government wasn’t so bad, despite the horror stories coming from much of the Cambodian-American community.

He was impressed by his meeting with the 38-year-old prime minister, Hun Sen, and left Cambodia confident that it was no longer ruled by a “strongman” like Pol Pot or Sihanouk. “Finally, I am certain that this Administration will welcome free elections and a peaceful settlement of differences among Cambodians when the dust settles,” he concluded.

Within two years, Cambodia’s warring factions signed a UN-brokered peace accord, and Hun Sen would indeed agree to watershed elections in 1993, which he lost to the royalist Funcinpec party and refused to accept, leading to a power sharing agreement with Prince Norodom Ranariddh.

By 1995, Chhang Song had left his wife and three children in Virginia and moved back to Cambodia. The one-time information minister went to work as a personal advisor for Chea Sim, then the president of the National Assembly.

That gave him a closeup view of factional fighting that broke out on the streets of Phnom Penh in 1997, in what many Western observers called a coup against Funcinpec. Chhang Song was sent back to the U.S. to tell the CPP’s side of the story, as a “special envoy” to the acting head of state.

“It was not a coup d'etat because there had not been any contemplation — no change in the government, no ideas of overthrowing the government, no change in Cambodian institutions…neither by Hun Sen nor by people in his party, nor by anybody else,” he told reporters at the National Press Building in Washington D.C.

Nonetheless, Funcinpec would begin its long slide toward irrelevance after the fighting, and the CPP regained full control of the government, which it maintains to this day.

In 1999, Chhang Song became a CPP senator, part of a small group of ruling party figures who returned to Cambodia from abroad and were given seats of prominence. He promised to be a truth speaker, and was among the critics of a penal law that expanded policing powers.

"We cannot close our eyes when we approve an important bill. We have to talk to find out what is right and wrong, because there was confusion written in the law," he told the Phnom Penh Post newspaper at the time.

Within two years of joining the Senate, Chhang Song was sacked along with some of the others.

Heng Samrin, now the National Assembly president, told the Phnom Penh Post that the returnee senators had “abused the internal regulations and political platform of the party.”

Chhang Song’s dream of bringing democracy to Cambodia had come up against the harsh reality of Cambodian politics. Chea Vannath, a prominent political analyst and civil society leader, told The Cambodia Daily at the time that the free-speaking senators had become an unnecessary liability.

Youk Chhang said his cousin — a “perfect” writer in Khmer — had confused politics with poetry. “He was desperate to be recognized. Again, you know, you can do fiction in the movies or a drama. It’s not a drama. He could not direct the drama. It’s real life.”

That ouster largely marked the end of Chhang Song’s formal role in Cambodian politics, but he would continue to be an adamant CPP supporter, using his Facebook page and other outlets to criticize opposition leader Sam Rainsy and oppose US policies punishing Hun Sen’s regime.

In 2001, Chhang Song moved back to the U.S., this time to Long Beach, California, where many in the large Cambodian community already were aware of him through politics or his non-profit work. In his first year there, he was the grand marshal of the Khmer New Year Parade, said Keo Sam An, a cousin who remained close to him until his death.

“He easily fit in and had lots of friends here, with relatives here and there,” he said. But Chhang Song’s politics made him something of a divisive figure too. “Half liked him, you know, and half ignored him, but he tends to focus on whoever welcomes him,” the cousin added.

In 2006, a friend introduced Chhang Song to Run Sum, a seamstress who became his life partner. He suffered a series of strokes, and was in a wheelchair for his last decade. “She's really an angel,” Keo Sam An said of Run Sum. “Without her to take care of him…his life would have been cut short.”

Chhang Song and Run Sum regularly attended Cambodian festivals and fundraisers for their preferred local politicians — and he kept writing and thinking about politics. And he regularly traveled back to Cambodia.

In 2019, when Sam Rainsy was threatening to return to Cambodia and join fellow “patriots” in arresting Hun Sen, Chhang Song rightly predicted that his bellicose rhetoric would open the legal floodgates.

“In this game of endurance and legitimacy, the sitting Prime Minister can use his power to smash the ball back into his Opponent's court, win the game and end the agony,” he wrote.

Laurie, who stayed in touch with Chhang Song over the years, said his friend always wanted to stay in the mix, but didn’t seem to him to be a “true believer” in either Lon Nol or Hun Sen.

“He was A) a survivor, and B) always wanting somehow to remain relevant. I think it was very irritating to him as years went on, when he would come back to Cambodia…he was no longer a relevant figure. And I think he really struggled with that.”

Chhang Song made a final trip to Cambodia in 2020, just weeks before COVID-19 would begin its deadly spread across the world. He met with some of the same CPP top brass who were in power during his trip in 1989, and even spoke briefly with Hun Sen, who stopped by his table at a gathering of members of the media.

“On his way out, Samdech the Prime Minister stopped by my table again, bowed to reach me in my wheelchair and hugged me,” Chhang Song wrote on Facebook, along with a photo of the moment. “With much affection in his look and in the tone of his voice, SAMDECH said ‘goodbye, Ta,’ which means 'goodbye, Grandfather.'”

For the next two and half years, Chhang Song’s interactions with the world would largely be limited to Facebook. He was fastidious in sharing news about the pandemic, both around the world and in Long Beach, and concerned by the anti-vaccine voices undermining public health advice.

“I'm scared, very scared, my friends. I worry whether I'd live long enough to see the return to normal,” he wrote in July 2021.

Chhang Song made it through the worst of the pandemic, and was able to visit with friends again and join community celebrations during his final months.

Until the end, new stories kept gathering in his head. In June 2020, he compared the abundance of stories still left untold to his father’s oxcart, loaded with sacks of rice and corn, recalling his childhood trips from the family’s flooded rice field to their home set among the Cardamom mountains.

Two oxen pulled the creaky old cart while, perched on the top of it and with a long whip in my hands, I urged the brave cattle to move on so we could reach the destination before the sunset. Like the old wheels of the cart which kept squeaking, my mind now keeps sharing my thoughts with you, knowing full-well they would make no difference to the busy world.

In the coming weeks, the ashes of Chhang Song’s body will be returned to the pagoda in Takeo province where he learned to read and write as a boy, said Run Sum. Friends and relatives will gather around a stupa being built for his remains, sharing his stories and recalling a piece of Cambodia’s history that would have been lost without him.