Native Americans

Tribal Courts Across US Expanding Holistic Alternatives to Criminal Justice System

Inside a jail cell at Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, Albertyn Pino's only plan was to finish the six-month sentence for public intoxication, along with other charges, and to return to her abusive boyfriend.

That's when she was offered a lifeline: An invitation to the tribe's Healing to Wellness Court. She would be released early if she agreed to attend alcohol treatment and counseling sessions, secure a bed at a shelter, get a job, undergo drug testing and regularly check in with a judge.

Pino, now 53, ultimately completed the requirements and, after about a year and a half, the charges were dropped. She looks back at that time, 15 years ago, and is grateful that people envisioned a better future for her when she struggled to see one for herself.

"It helped me start learning more about myself, about what made me tick, because I didn't know who I was," said Pino, who is now a case manager and certified peer support worker. "I didn't know what to do."

The concept of treating people in the criminal justice system holistically is not new in Indian Country, but there are new programs coming on board as well as expanded approaches. About one-third of the roughly 320 tribal court systems across the country have aspects of this healing and wellness approach, according to the National American Indian Court Judges Association.

Combining legal advocacy and support

Some tribes are incorporating these aspects into more specialized juvenile and family courts, said Kristina Pacheco, Tribal Healing to Wellness Court specialist for the California-based Tribal Law and Policy Institute. The court judges association is also working on pilot projects for holistic defense — which combine legal advocacy and support — with tribes in Alaska, Nevada and Oklahoma, modeled after a successful initiative at the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana.

"The thought and the concept will be different from tribe to tribe," said Pacheco. "But ultimately, we all want our tribal people ... to not hurt, not suffer."

People in the program typically are facing nonviolent misdemeanors, such as a DUI, public intoxication or burglary, she said. Some courts, like in the case of Pino, drop the charges once participants complete the program.

A program at the Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe in Washington state applies restorative principles and assigns wellness coaches to serve Native Americans and non-Natives in the local county jail, a report released earlier this year by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation outlined. The Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma has a reintegration program that includes financial support and housing services, as well as cultural programming, career development and legal counsel. In Alaska, the Kenaitze Indian Tribe's wellness court helps adults in tribal and state court who are battling substance abuse and incorporates elements of their tribe's culture.

"There's a lot of shame and guilt when you're arrested," said Mary Rodriguez, staff attorney for the court judges association. "You don't reach out to those resources, you feel that you aren't entitled to those resources, that those are for somebody who isn't in trouble with the law."

'You are better than the worst thing you've done'

"The idea of holistic defense is opening that up and reclaiming you are our community member, we understand there are issues," Rodriguez said. "You are better than the worst thing you've done."

The MacArthur Foundation report outlined a series of inequities, including a complicated jurisdictional maze in Indian Country that can result in multiple courts charging Native Americans for the same offense. The report also listed historical trauma and a lack of access to free, legal counsel within tribes as factors that contribute to disproportionate representation of Native Americans in federal and state prisons.

Advocates of tribal healing to wellness initiatives see the approaches as a way to shift the narrative of someone's life and address the underlying causes of criminal activity.

There isn't clear data that shows how holistic alternatives to harsh penalization have influenced incarceration rates. Narrative outcomes might be a better measure of success, including regaining custody of one's children and maintaining a driver's license, said Johanna Farmer, an enrolled citizen of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota and a program attorney for the court judges association.

Some tribes have incorporated specific cultural and community elements into healing, such as requiring participants to interview their own family members to establish a sense of rootedness and belonging.

"You have the narratives, the stories, the qualitative data showing that healing to wellness court, the holistic defense practices are more in line with a lot of traditional tribal community practices," Farmer said. "And when your justice systems align with your traditional values or the values you have in your community, the more likely you're going to see better results."

While not all of these tribal healing to wellness programs have received federal funding, some have.

Between 2020 and 2022, the U.S. Department of Justice distributed more than a dozen awards that totaled about $9.4 million for tribal healing to wellness courts.

This year, the Quapaw Nation in Oklahoma started working on a holistic defense program after seeing a sharp increase in cases following a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said a large area of eastern Oklahoma remains a Native American reservation.

So far this year, about 70 cases have been filed, up from nearly a dozen in all of 2020, said Corissa Millard, tribal court administrator.

"When we look at holistic approaches, we think, 'What's going to better help the community in long term?'" she said. "Is sending someone away for a three-year punishment going to be it? Will they reoffend once they get out? Or do you want to try to fix the problem before it escalates?"

For Pino, the journey through Laguna Pueblo's wellness court wasn't smooth. She struggled through relapses and a brief stint on the run before she found a job and an apartment to live in with her son nearby in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her daughters live close by.

She largely credits the wellness court staff for her ability to turnaround her life, she said.

"They were the ones that stood by me, regardless of what I was choosing to do; that was the part that brought me a lot of hope," she said. "And now where I'm at, just to see them happy, it gets emotional, because they never let go. They never gave up on me."

Native American News Roundup Aug. 13-19, 2023

Here are some of the Native American-related stories that made headlines this week:

Native Hawaiians missing, dead or displaced by Maui wildfires

Native Hawaiians – the Kānaka Maoli – are struggling to comprehend the devastation caused by wildfires in Maui, last week. At least 111 people – including children – are dead, and that number is expected to rise as the search for remains continues.

Hawaii Gov. Josh Green told CNN on Wednesday that “probably over 1,000” residents are still missing.

The fire, which broke out August 8, devastated the community of Lahaina, leaving thousands of people unhoused. Lahaina, an important Native Hawaiian cultural center, was between 1820 and 1845 the capital of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Officials say it will cost more than $5.5 billion to rebuild.

Read more:

Biden administration injecting funds into tribal clean energy programs

The Department of the Interior this week announced a new program that will initially make available $72.5 million to help Native American communities bring clean energy to tribal homes.

An estimated 17,000 tribal families live without electricity, most of them in the Southwest and Alaska. The Tribal Electrification Program will provide money and expertise to help tribes electrify homes using environmentally friendly energy sources.

It will also help homes that already have electricity switch to cleaner energy options and provide support for home repairs and changes needed to make this happen.

The new funding announcement is part of an overall $150 million investment from the Inflation Reduction Act to support the electrification of homes in tribal communities.

“Climate change is the crisis of our lifetimes and has left far too many communities managing for worsening water challenges, extreme heat, devastating wildfires and unprecedented storms. Every action we take now to lessen the impacts for future generations is critical,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said.

“Through President [Joe] Biden’s Investing in America agenda, we’re launching a new program to electrify Indian Country to provide reliable, resilient energy that Tribes can rely on, and advance our work to tackle the climate crisis and build a clean energy future.”

Read more:

Interior Department to fund water systems in drought-ridden Upper Colorado River Basin

In a related story, the Department of the Interior this week also announced it will make available $50 million over the next five years to improve key water supply systems and drought-related data collection across the Upper Colorado River Basin.

“The Biden-Harris administration is committed to bringing every tool and every resource to bear to as we work with states, Tribes and communities throughout the West to find long-term solutions in the face of climate change and the sustained drought it is creating,” Deputy Secretary Tommy Beaudreau said.

“As we look toward the next decade of Colorado River guidelines and strategies, we are simultaneously making smart investments now that will make our path forward stronger and more sustainable.”

Read more:

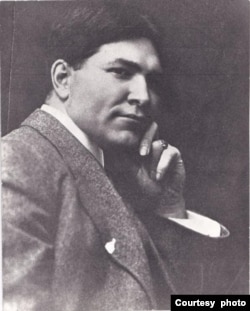

Celebrated Menominee activist Ada Deer dies

Ada Deer, the first woman to lead the Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, died on Tuesday at the age of 88.

A well-known champion for Native American rights and sovereignty, Deer grew up on the Menominee Indian Reservation in Keshena, Wisconsin. After earning her bachelor’s and master’s degrees, she worked as a social worker in New York and Wisconsin.

In 1954, during the so-called “Termination Era,” Congress withdrew its recognition of the Menominee tribe, which meant their lands were now under state control and up for development. It also meant the tribe lost all federal benefits, such as health care and education, and was plunged into poverty.

In the early 1970s, Deer and other Menominee supporters launched a grassroots movement — Determination of Rights and Unity of Menominee Shareholders, or DRUMS — in protest, and took their case to Washington.

“You don’t have to collapse just because there’s a federal law in your way. Change it,” she told The Washington Post in 1973.

In late 1973, President Richard Nixon signed the Menominee Restoration Act, reinstating the tribe’s protected status and benefits.

President Bill Clinton in 1973 appointed her assistant secretary for Indian Affairs at the Interior Department, overseeing the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Read more:

Federal judge in Wisconsin upholds tribe’s sovereignty over roadways

A federal judge this week dismissed a lawsuit that aimed to force the Lac du Flambeau Tribe in Wisconsin to remove road barricades it had put in place in January.

The blocked roads were built on tribal land in the 1960s and are the only route in and out for non-Natives living on the reservation. Land agreements allowing them to use the roads expired in 2013, and negotiations to extend them have so far failed. The Lac du Flambeau Tribal Council says it is owed $20 million for trespassing on its land since the easements expired.

A group of non-tribal residents in February filed suit against the 12-member tribal council. The court held oral arguments June 7, 2023, and on Tuesday, U.S. District Judge William Conley dismissed the lawsuit altogether, acknowledging tribal sovereign rights over the roads, a matter over which federal courts lack jurisdiction.

Read more:

Native American Journalists Association rebrands

Members of the Native American Journalists Association have voted to change the organization’s name to the Indigenous Journalists Association (IJA).

They voted 89 to 55 in favor of the change during their annual conference, which was hosted in Winnipeg last week.

Francine Compton, IJA associate director, said the move was made to match international language and to ensure all First Nations, Metis, Native American and Inuit journalists are included and supported.

"It means a whole lot to me, that I can now have this organization with a name where people in my own community can look at it and say, 'That's for me,'" said Compton, who is Anishinaabe from the Sandy Bay Ojibway First Nation, 131 kilometers northwest of Winnipeg.

The organization also updated the logo from NAJA with a feather to a stylized “IJA,” above.

Read more: https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indigenous-journalists-association-1.6937231

Ada Deer, Influential Native American Leader, Dies at 88

Ada Deer, an esteemed Native American leader from the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the first woman to lead the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, has died at age 88.

Deer passed away Tuesday evening from natural causes, her godson Ben Wikler, chair of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin, confirmed on Wednesday. She had entered hospice care last month.

Trailblazer, advocate

Born August 7, 1935, on the Menominee reservation in Keshena, Wisconsin, Deer is remembered as a trailblazer and fierce advocate for tribal sovereignty. She played a key role in reversing Termination Era policies of the 1950s that took away the Menominee people's federal tribal recognition.

"Ada was one of those extraordinary people who would see something that needed to change in the world and then make it her job and everyone else's job to see to it that it got changed," Wikler said. "She took America from the Termination Era to an unprecedented level of tribal sovereignty."

Deer was the first member of the Menominee Tribe to graduate from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and went on to become the first Native American to obtain a master's in social work from Columbia University, according to both schools' websites.

In the early 1970s, Deer organized grassroots political movements that fought against policies that had rolled back Native American rights. The Menominee Tribe was placed under the control of a corporation in 1961, but Deer's efforts led President Richard Nixon in 1973 to restore the tribe's rights and repeal termination policies.

Soon after, Deer was elected head of the Menominee Restoration Committee and began working as a lecturer in American Indian studies and social work at the University of Wisconsin. She unsuccessfully ran twice for Wisconsin's secretary of state and in 1992 narrowly lost a bid to become the first Native American woman elected to U.S. Congress.

President Bill Clinton appointed Deer in 1993 as head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, where she served for four years and helped strengthen federal protections and rights for hundreds of tribes.

She remained active in academia and Democratic politics in the years before her death and was inducted into the National Native American Hall of Fame in 2019.

Earlier this month, Governor Tony Evers proclaimed August 7, Deer's 88th birthday, as Ada Deer Day in Wisconsin.

"Ada was one-of-a-kind," Evers posted Wednesday on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter. "We will remember her as a trailblazer, a changemaker, and a champion for Indigenous communities."

Native American News Roundup August 6-12, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

New national monument will curb, not halt, uranium mining near Grand Canyon

President Joe Biden was in Arizona on Tuesday, where he designated more than 404,000 hectares of land around the Grand Canyon as a national monument, the fifth of his presidency.

America’s natural wonders are our nation’s heart and soul,” Biden said, speaking at Red Butte Airport in Williams, Arizona. “And so, today, I’m proud to use my authority under the Antiquities Act to protect almost 1 million acres of public land around Grand Canyon National Park as a new national monument, to help right the wrongs of the past and conserve this land of ancestral footprints for all future generations.”

The monument will now be known as Baaj Nwaavjo l’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument. The name is a blending of the languages of two tribes, the Havasupai and Hopi, who are among more than a dozen tribes whose ancestors made their home here. See video below to understand more about the name.

In 2012, the Interior Department enacted a 20-year moratorium on any new uranium mining around the Grand Canyon. Mining operations in the area that predate that moratorium will be allowed to continue.

VOA’s Matt Dibble filed this story:

Group calls on Washington football team to ‘Reclaim the Redskins’

Name changes are on the agenda of another group this week: the Native American Guardians Association (NAGA) sent a three-page letter to the owners and leaders of the Washington Commanders football, calling on them to change the team’s name back to the “Washington Redskins.”

According to the letter posted on the NAGA Facebook page, the group aims “to stop the further cancel culture” against Native Americans.

“As you are undoubtedly aware, the Redskins had a long and mutually beneficial relationship with the American Indian community, dating back to their founding in 1932 as the Boston Braves, when their original coach was Native American (and former Carlisle Indian star) Lone Star Dietz.”

It is a claim former Redskins owner Dan Snyder often used to justify keeping the team’s name. But there’s a bit of a problem with the assertion: that coach was born William Henry Dietz and served time in jail after twice being indicted for faking Native American identity.

VOA reached out to Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee activist Suzan Harjo, who was instrumental in the fight to get the Redskins name changed.

"Dietz was definitely a pseudo-Indian who stole a dead man’s identity and tried to steal his money and land, but didn’t get away with that," she said via Facebook.

NAGA has threatened to encourage a national boycott of the team; in June, it launched an online petition that has garnered more than 75,000 signatures.

Read more:

Report: Dams have played big role in Native American land loss

Today, federally recognized tribes’ federal tribal landholdings across the entire U.S. total approximately 28.3 million hectares (70 million acres), less than 3% of the total U.S. land area. Most of this is due to the colonial taking of Native American land.

A new report from Penn State University looks at an understudied cause of tribal land dispossession: Dams.

A team of researchers looked at data from federal Indian reservations and Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Areas near about 8,000 dams across the country. They also measured the size of dam reservoirs.

They conclude that 424 dams have flooded more than 520,000 hectares (1.13 million acres) of tribal land — an area larger than Great Smokey Mountains National Park, Grand Teton National Park and Rocky Mountain National Park combined.

“The consequences of dam-induced land loss are far-reaching,” lead study author Heather Randell said. “The disruption of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems not only devastates natural resources but also destroys culturally significant sites.”

Randall also said that the impact on tribal communities’ livelihoods is “equally severe.”

Read the study and its recommendations here:

Remembering Red Bird

The Violin Channel this week looks at the life and times of Zitkala-Sa (“Red Bird”), a Yankton Dakota writer, composer and activist for Native American and women’s rights.

She was born in 1876 at the Yankton Sioux Agency in South Dakota to a Dakota mother and a white father. She was sent to be educated at a Quaker boarding school in Indiana, where she was given the name Gertrude Simmons. Later, she studied music at the prestigious New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

She taught for two years at the Carlisle Industrial Indian School in Pennsylvania and wrote about the experience in her 1921 book, “American Indian Stories,” and would go on to become a celebrated author who influenced Congress to pass the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, which granted full citizenship rights to Native Americans.

Read more and watch a documentary on her life here:

- By Matt Dibble

Biden Creates New National Monument Near Grand Canyon

U.S. President Joe Biden was in Arizona Tuesday to mark the creation of a new national monument near the Grand Canyon to protect more than 4,000 square kilometers of land sacred to Native Americans. Matt Dibble has the story.

Biden Designates National Monument Near Grand Canyon

Declaring it good "not only for Arizona but for the planet," President Joe Biden on Tuesday signed a national monument designation for the greater Grand Canyon, turning the decades-long visions of Native American tribes and environmentalists into reality.

Coming as Biden is on a three-state Western trip, the move will help preserve about 4,046 square kilometers (1,562 square miles) just to the north and south of Grand Canyon National Park. It was Biden's fifth monument designation.

Tribes in Arizona have been pushing the president to use his authority under the Antiquities Act of 1906 to create a new national monument called Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukveni. "Baaj Nwaavjo" means "where tribes roam," for the Havasupai people, while "I'tah Kukveni" translates to "our footprints," for the Hopi tribe.

"Preserving these lands is good, not only for Arizona but for the planet," said Biden, who spoke with a mountain vista behind him, using a handheld microphone against the wind and wearing a baseball cap and dark sunglasses against the sunshine and heat. "It's good for the economy. It's good for the soul of the nation."

Living up to treaty obligations

Biden likened the designation to his administration's larger push to combat climate change and noted this summer's extreme heat, which has been especially punishing in places like Phoenix.

Biden said the new designation would see the federal government live up to its treaty obligations with Native American tribes after many were forced in decades past from their ancestral homes around the Grand Canyon as officials developed the site of the national park.

"At a time when some seek to ban books and bury history, we're making it clear that we can't just choose to learn what we want to learn," Biden said, a reference to his frequent criticism of some top Republicans who have sought to impose limits on school libraries, citing parental complaints about explicit material.

Arizona key in election

The political stakes are high. Arizona is a key battleground state that Biden won narrowly in 2020, becoming the first Democrat since Bill Clinton in 1996 to carry it. And it's one of only a few genuinely competitive states heading into next year's election. Winning Arizona would be a critical part of Biden's efforts to secure a second term.

Republican lawmakers and the mining industry have touted the area's economic benefits and argued that mining is a matter of national security.

Representatives Bruce Westerman, chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, and Paul Gosar, an Arizona Republican who also holds a leadership position on the committee, released a letter to Biden on Tuesday, criticizing the designation and suggesting it "would permanently withdraw the richest and highest-grade uranium deposits in the United States from mining — deposits that are far outside the Grand Canyon National Park."

The Interior Department, reacting to concerns over the risk of contaminating water, enacted a 20-year moratorium on the filing of new mining claims around the national park in 2012.

Existing mining claims will not be affected by this designation, senior Biden administration officials counter. Furthermore, the monument site encompasses about 1.3% of the nation's known and understood uranium reserves. Officials say there are significant resources in other parts of the country that will remain accessible.

Invitees at Tuesday's event included Yavapai-Apache Nation Chairwoman Tanya Lewis, Colorado River Indian Tribes Chairwoman Amelia Flores, Navajo President Buu Nygren and Havasupai Tribal Councilwoman Dianna Sue White Dove Uqualla.

Uqualla is part of a group of tribal dancers who performed a blessing at the designation ceremony.

"It's really the uranium we don't want coming out of the ground because it's going to affect everything around us — the trees, the land, the animals, the people," Uqualla said. "It's not going to stop."

After Arizona, Biden will go on to Albuquerque in New Mexico on Wednesday, where he will talk about how fighting climate change has created new jobs. During a visit to Salt Lake City in Utah on Thursday, the president will mark the first anniversary of the PACT Act, which provides new benefits to veterans who were exposed to toxic substances. He'll also hold a reelection fundraiser in each city.

Native Americans Share Memories of Indian Boarding Schools with US Officials

U.S. Department of the Interior officials are visiting Native American communities to learn about the impact of government-run residential schools on former students and their families. The institutions once suppressed Native cultures, but the few schools that remain now celebrate them. Mike O’Sullivan reports from Riverside, California.

Native American News Roundup July 30 - August 5, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories and features making headlines this week:

HHS to fund development of tribal produce prescription programs

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has granted $2.2 million to five tribes to support the development of produce prescription programs.

Broadly, these programs provide free or discounted fruit, vegetables and other nutritious foods for patients living with food insecurity or diagnosed with certain health conditions. Healthcare providers write prescriptions that patients can take to be filled in retail food stores.

Awards of $500,000 each will go to the Laguna Healthcare Corporation, which serves the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico; the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma; the Navajo Health Foundation; the Pascua Yaqui Tribe in Arizona; and the Rocky Boy Health Center, which serves Chippewa Cree on the Rocky Boy Reservation in Montana.

About one in four Native Americans experience food insecurity, compared to one in nine Americans overall, and they also experience high rates of diabetes and obesity.

Read more:

Oklahoma governor sues state lawmakers in over tribal compacts

Last week, VOA reported that Oklahoma’s majority-Republican Senate overrode Governor Kevin Stitt’s vetoes of two bills that would extend compacts between the state and tribes that split proceeds from tobacco and vehicle registrations.

Stitt’s lawyers on Monday filed a lawsuit against Oklahoma House Speaker Charles McCall and Senate President Pro Tem Greg Treat, arguing that only the governor has the authority to negotiate tribal contacts.

Oklahoma speaker McCall called the lawsuit “frivolous.”

For his part, Treat accused the governor of turning his back on “all four million Oklahomans, the legislative process and Oklahoma’s tribal partners.”

Read more:

Tesla CEO Elon Musk skirts state laws by operating on tribal land

Electric car manufacturer Tesla will soon open a showroom on the Mohegan Reservation in Connecticut, expanding its presence on tribal lands.

Tesla is so far the only carmaker that sells directly to buyers. All other auto manufacturers sell through independently owned dealerships. Many U.S. states have franchise laws that ban car makers from selling directly to customers without going through independent dealerships. Other states limit the number of stores Tesla can open.

CEO Elon Musk gets around these laws by negotiating with tribes to place showrooms on tribal land, where these laws do not apply.

In September 2021, Tesla opened its first showroom in a former casino on the Nambé Pueblo near Sante Fe, New Mexico, and a second on the Santa Ana Pueblo, near Albuquerque. Another Tesla showroom is planned to open in 2025 on the Oneida Reservation in New York.

Read more:

Tribes seek to find, protect bats in Pacific Northwest

The Native American Fish and Wildlife Society, Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, U.S. Geological Survey, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Park Service and Oregon State University are hosting the first-ever Pacific Northcoast Bat Workshop on the Yakama Nation in Washington state.

The two-day workshop will address threats to bats on tribal lands, particularly White Nose Syndrome (WNS), a fungal infection that has killed more than 6 million bats in eastern North America since 2006 — decimating whole colonies. It showed up in the Pacific Northwest in 2016.

Bats are often misunderstood and feared but play a vital role in U.S. agriculture. By eating so many insects and rodents, they save U.S. farmers more than $3 billion in crop damage and pesticide costs each year.

Read more:

Federal courts highlight career of Hopi federal judge

As part of its video series “Pathways to the Bench,” U.S. Federal Courts this week focused on Diane Humetewa, a member of the Hopi Tribe in northwest Arizona, who in 2014 became the first Native American woman to serve as a U.S. federal judge.

Born and raised in Phoenix, Arizona, she and her family kept close ties to Kykotsmovi Village, on the Hopi Reservation’s Third Mesa. In this video, she discusses challenges she faced along the way to federal judgeship—and her reluctance to share her cultural identity with non-Natives.

New Mexico honors two prominent Native American artists

Two Native Americans have been named among the winners of the 2023 New Mexico Governor’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts. They are: experimental composer, performer and installation artist Raven Chacon, Navajo, who in 2022 became the first Native American awarded the Pulitzer Prize in music for his 2021 composition “Voiceless Mass,” which debuted in a Milwaukee, Wisconsin, church (see video below).

Also named is haute couture fashion designer Patricia Michaels, a member of the Water Clan of the Taos Pueblo. A former runner-up on the American fashion competition TV show “Project Runway,” Michaels has designed and created costumes for opera and theater productions, custom resort uniforms and red-carpet gowns. In 2014, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian board of directors in New York honored her as the first recipient of its Arts and Design Award.

New Mexico’s Governor's Awards for Excellence in the Arts was established in 1974 to celebrate the significance of the arts to the State of New Mexico.

See the full list of this year’s winners here:

Tribal Canoe Journey Returns to Washington State After COVID-19 Break

For thousands of years, canoes were the primary means of travel for the Native Americans known as the Coast Salish peoples. Tribal Canoe Journey, an event celebrating indigenous tribes of the West Coast, is back after a pandemic hiatus. Natasha Mozgovaya has more. Camera: Natasha Mozgovaya.

Two Tribal Nations to Open Minnesota's First Legal Recreational Marijuana Dispensaries

At least two tribal nations are expected to open Minnesota's first recreational marijuana dispensaries in August as recreational marijuana becomes legal to possess and grow in the state on Tuesday.

Following a council vote on Friday, the White Earth Nation in northwestern Minnesota legalized recreational cannabis and will begin selling it sometime in the first half of August, Minnesota Public Radio reported. Both tribal members and non-tribal adults 21 years and older would be able to purchase from the nation's dispensary.

Weeks earlier, NativeCare — a tribal-run medical marijuana provider — announced a recreational marijuana dispensary expected to open shortly on Red Lake Nation once the new law takes effect, the Star Tribune reported. The nation is also in northwestern Minnesota.

The band could've started selling recreational marijuana at that time but decided to wait until Minnesota's new marijuana law legalizes possession statewide.

"Our intention is to be a good partner and ultimately fill the void for people who intend to use cannabis," Red Lake tribal secretary Sam Strong told the Star Tribune.

The state's Democratic-controlled Legislature approved a massive marijuana legalization bill this year, which Democratic Governor Tim Walz signed in May.

White Earth Nation and Red Lake Nation plan to take advantage of their sovereignty and allow sales right away. But the state projects most legal retail sales won't begin until early 2025, while it creates a licensing and regulatory system for the new industry.

Minnesota is the 23rd state to legalize recreational marijuana, more than a decade after Colorado and Washington did so.

Native American News Roundup July 23-29, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Archaeologists fail to find children’s remains at Indian boarding school site

Nebraska state archaeologists say they’ve ended a two-week search for the graves of former students at the Indian Industrial School in Genoa, Nebraska, after failing to find any human remains.

Researchers believe more than 80 students died at the school, most from infectious diseases. So far, they’ve identified 49 students who died at the school. Some were returned home for burial, but others are believed to have been buried at the school.

State archaeologist Dave Williams said his team will now reevaluate the data and consult with the dozens of tribes that lost ancestors to the school.

Read more:

Kansas university scholars accused of race shifting

Native American groups and individuals have accused three University of Kansas professors of “Pretendianism,” that is, falsely claiming Native American ancestry.

The most prominent of the three is Kent Blansett, associate professor of Indigenous studies and history and founder of the American Indian Digital History Project, which digitizes rare Indigenous newspapers, photographs and other archival materials.

As VOA has reported previously, Indigenous scholars complain that academics frequently manufacture an Indigenous identity for personal, professional and financial gain.

Read more:

US Appeals Court to review Wyoming convictions against Crow hunters

A federal judge in Wyoming has agreed to review a 34-year-old dispute over whether the Crow Tribe in Montana has the right to hunt beyond reservation borders.

In late 1989, Wyoming fined Crow citizen Thomas L. Ten Bear for shooting an elk in Wyoming’s Big Horn Forest.

The Crow sued Wyoming, arguing that the 1868 treaty signed with the U.S. gave them the right to hunt on unoccupied U.S. lands “so long as game may be found” and relations with whites were peaceful. Wyoming ruled against the Crow, saying those treaty rights expired when Wyoming became a U.S. state.

But 25 years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in another case that Crow hunting rights did not expire.

The Crow have since fought to have the original ruling overturned. This week, a federal appeals judge said he will “more thoroughly” review the facts.

Read more:

Oklahoma Senate overrides veto on compacts with tribes

Oklahoma’s majority-Republican Senate on Monday overrode Governor Kevin Stitt’s vetoes of two bills that would extend for another year tobacco and vehicle registration compacts the state has made with Oklahoma tribes.

The state currently holds agreements with tribes to split the tax revenue from tribal sales of tobacco to non-Natives and from motor vehicle registrations and tags.

The Cherokee Phoenix reports that, according to the current motor vehicle compact, the Cherokee Nation allocates 38% of car registration revenue to public school districts in or near the reservation — in 2023, that amount was $7.8 million; since 2002, the tribe has given more than $84 million to schools.

Stitt has said the compacts shortchange the state, and he is looking to limit the compacts to trust land only.

“I am trying to protect eastern Oklahoma from turning into a reservation, and I’ve been working to ensure these compacts are the best deal for all 4 million Oklahomans,” Stitt posted on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter.

It is a reference to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which held that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation was never formally disestablished and, therefore, at least for criminal jurisdiction purposes, covered half of the state.

Read more:

Native Americans: There’s nothing funny about smallpox joke

The new “Barbie” film, which opened last weekend to record profits, has provoked the ire of many Native Americans. At issue is a joke that referenced the devastating impact introduced diseases had on Indigenous populations.

Here’s the plot: Barbie (Margot Robbie) and Ken (Ryan Gosling) travel from the pink and perfect Barbieland to the real world, which isn’t so pretty.

Ken, inspired by the patriarchy of the real world, returns home and turns Barbieland into the patriarchal Kenland. Toward the end of the film, Ken jokes about how easy it was to make the change: "I just explained the immaculate logic of patriarchy, and they crumbled."

The character Gloria (America Ferrera), exclaims, “Oh my god! This is like in the 1500s with the Indigenous people and smallpox. They had no defenses against it!”

Keeli Siyaka, Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota, has posted an online petition calling on Warner Brothers and film director Greta Gerwig to remove that line from the film.

“Seeing as no one in the audience laughed, I don't think anyone would miss it, and if they do, we have a problem,” she stated.

Read more:

Native American News Roundup July 16-22, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Treasury secretary addresses poor access to cash, credit in Indian Country

The U.S. Financial Literacy Commission met Thursday to discuss barriers to financial stability in Indian Country.

"One of those main barriers is financial literacy – the understanding of concepts like saving, investing and debt that leads to an overall sense of financial well-being," U.S. Treasury Secretary Lynn Malerba, chief of the Mohegan Tribe, told the commission.

She cited a lack of accessible banks.

"Some banks are hesitant to both locate and lend on reservations due to a lack of knowledge in navigating sovereign immunity, tribal jurisdiction and the status of land held in trust," she said.

Malerba noted that Indian Country is growing, and so, too, is Native buying power. She called on the commission to help Native business owners and workers prosper.

Read more:

Indian boarding school in Oregon misused funds, including student monies

A federal audit of finances at the Chemawa Indian Boarding School in Oregon shows that the school improperly used more than $590,000 in federal funds to purchase "inappropriate and potentially wasteful items." These include excavating equipment, a pole barn and a horse trailer.

The Interior Department's inspector general conducted an audit of the school's accounting processes and the Bureau of Indian Education's role in overseeing those finances.

Bureau of Indian Affairs policy allows junior and senior high schools enrolling one hundred or more students to operate a school bank for so-called "student enterprise moneys," which includes money raised by student clubs, donations and students' own funds.

Federal law also allows those schools to lease land to businesses.

Auditors say Chemawa Indian Boarding School mismanaged all student enterprise funds, averaging $600,000 over a three-year period; improperly accounted for businesses leases; and "inappropriately managed" property.

Furthermore, auditors say the Bureau of Indian Education did not live up to its supervisory responsibilities.

Read the report and auditors' recommendations here:

Biggest lithium mine in North America gets green light to proceed

A federal appeals court this week ruled that the U.S. Interior Department did not break any environmental laws when it approved the construction of a lithium mine near Nevada's border with Oregon.

This means that Lithium Nevada can continue the construction of the Thacker Pass Lithium mine.

Environmental groups sued to block it, arguing that the mine would irreversibly harm the environment. Co-plaintiffs include a Nevada cattle rancher who owns land above and below the site, tribes of the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, the Burns Paiute Tribe, and the Atsa Koodakuh wyh Nuwu (" People of the Red Mountain"), an organization of Paiute and Shoshone people from the Fort McDermitt and Duck Valley reservations.

Lithium Nevada will initially mine more than 2,300 hectares (more than 5,000 acres), but environmental groups say that future mining could expand to 6,900 hectares (17,000 acres).

Lithium is an essential component for building batteries for electric vehicles, which are vital to President Joe Biden's "clean energy by 2050" agenda.

Read more:

Ute Tribe says public schools are not educating tribal children

The Ute Tribe of Northeastern Utah says the state school system has failed to educate Ute children effectively. An investigation by the Salt Lake Tribune backs the claim.

"In 2020, 58% of Ute seniors in Duchesne County School District graduated, for example — that's lower than the percentage for students with disabilities," the Tribune reported Monday.

Documentation shows the problems date back decades and are rooted in racism. A 1996 report noted that during the Great Depression of the 1930s, more than half of the region's white people depended on emergency relief.

"Many [whites] blamed this on the fact that Indian land could not be taxed for the good of the county," that report read.

In some cases, white schools turned Ute children away altogether.

Read more:

Canadian Wildfires Hit Indigenous Communities Hard

EAST PRAIRIE METIS SETTLEMENT, Alberta — Carrol Johnston counted her blessings as she stood on the barren site where her home was destroyed by a fast-moving wildfire that forced her to flee her northern Alberta community two months ago.

Her family escaped unharmed, though her beloved cat, Missy, didn't make it out before a "fireball" dropped on the house in early May. But peony bushes passed down from her late mother survived and the blackened Mayday tree planted in memory of her longtime partner is sending up new shoots — hopeful signs as she prepares to start over in the East Prairie Métis Settlement, about 385 kilometers northwest of Edmonton.

"I just can't leave," said Johnston, 72, who shared a home with her son and daughter-in-law. "Why would I want to leave such beautiful memories?"

'We lost so much'

The worst wildfire season in Canadian history is displacing Indigenous communities from Nova Scotia to British Columbia, blanketing them in thick smoke, destroying homes and forests and threatening important cultural activities like hunting, fishing and gathering native plants.

Thousands of fires have scorched more than 110,000 square kilometers across the country so far. On Tuesday, almost 900 fires were burning— most of them out of control — according to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre website.

Fires aren't uncommon on Indigenous lands, but they're now occurring over such a widespread area that many more people are experiencing them at the same time — and some for the first time — stoking fears of what a hotter, drier future will bring, especially to communities where traditions run deep.

"I've never seen anything like this," said Raymond Supernault, chairman of the East Prairie Metis Settlement, where he said more than 85% of the 334-square-kilometer settlement burned in the first wildfire there in over 60 years. Fourteen houses and 60 other structures were destroyed by the intense, fast-moving fire that led to the evacuation of almost 300 people and decimated forested land.

"In blink of eye, we lost so much … it was devastating. I can't stress that enough," said Supernault, who said he hasn't seen any elk or moose, both important food sources, since the fire.

"We don't just jump in the car and go to the IGA," for groceries, Supernault said. "We go to the bush."

In Canada, 5% of the population identifies as Indigenous — First Nation, Metis or Inuit — with an even smaller percentage living in predominantly Indigenous communities. Yet more than 42% of wildfire evacuations have been from communities that are more than half Indigenous, said Amy Cardinal Christianson, an Indigenous fire specialist with Parks Canada.

As of Monday, 106 wildfires have affected 93 First Nations communities this year, and there have been 64 evacuations involving almost 25,000 people, according to Indigenous Services Canada.

It's not uncommon for Indigenous communities to evacuate repeatedly, Christianson said. A recent analysis of the Canadian Wildland Fire Evacuation database found that 16 communities were evacuated five or more times from 1980–2021 — all but two of them First Nations reserves, said Christianson, who participated in the analysis by the Canadian Forest Service.

Fires now "are so dangerous and so fast-moving" that evacuations increasingly are necessary, a challenge in some remote communities where there might be one road in, or no roads at all, said Christianson, who is Metis.

'Life-altering events'

Ken McMullen, president of the Canadian Association of Fire Chiefs and fire chief in Red Deer, Alberta — a province where about 19,800 square kilometers have already burned, compared to just over 1,800 square kilometers in all of 2022 — said some places burning again this year haven't fully recovered from previous fires.

"It's going to take a long time," said McMullen, calling it the worst fire season in Canadian history. "These are life-altering events."

Christianson said the effects will be felt for generations, because the intense heat is burning the soil and making it difficult for trees and other plants to regenerate.

She said Indigenous communities are increasingly vulnerable because they're often left out of decisions about forest management and fire response, and often can't afford to hire emergency managers. What's more, when fires affect urban centers at the same time, fire suppression shifts to larger communities.

Indigenous communities "really want to be leaders in managing fires in their territory," including a return to preventive burning that was long suppressed by the government, said Christianson.

The Algonquins of Barriere Lake in northern Quebec evacuated in June because of heavy smoke from wildfires that came within 15 kilometers of and almost surrounded the reserve where about 350 to 400 people live, often miles apart, said Chief Casey Ratt, who never experienced a forest fire before this year.

"Last year, me and my wife were talking about how many fires there were in Alberta, then boom! There were so many in Quebec this year," said Ratt. "I was like, 'Oh my gosh, now we're dealing with wildfires like they are out west.'"

But it also wasn't a total surprise, said Ratt, because summer heat is more intense and ice forms later in the winter and melts faster in the spring. That diminishes their ability to ice-fish and hunt for moose and beaver, which often requires crossing a lake to an island.

"Something is happening," said Ratt, who believes climate change is largely to blame. "I think this will be the norm moving forward."

The biggest concern is whether cultural traditions that have been passed down from generations of elders will survive into the future, said Supernault, from the East Prairie Métis Settlement.

"Our earth is changing ... and our traditional way of life is now put on hold," said Supernault. "You can't put a price on culture and traditional loss."

Pipestone Carvers Preserve Native Spiritual Tradition on Minnesota Prairie

Under the tall prairie grass outside this southwestern Minnesota town lies a precious seam of dark red pipestone that, for thousands of years, Native Americans have quarried and carved into pipes essential to prayer and communication with the Creator.

Only a dozen Dakota carvers remain in the predominantly agricultural area bordering South Dakota. While tensions have flared periodically over how broadly to produce and share the rare artifacts, many Dakota today are focusing on how to pass on to future generations a difficult skillset that’s inextricably linked to spiritual practice.

“I’d be very happy to teach anyone … and the Spirit will be with you if you’re meant to do that,” said Cindy Pederson, who started learning how to carve from her grandparents six decades ago.

Enrolled in the Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota Nation, she regularly holds carving demonstrations at Pipestone National Monument, a small park that encompasses the quarries.

In the worldview of the Dakota peoples, sometimes referred to as Sioux, “the sacred is woven in” the land where the Creator placed them, said Iyekiyapiwin Darlene St. Clair, a professor at St. Cloud State University in central Minnesota.

But some places have a special relevance, because of events that occurred there, a sense of stronger spiritual power, or their importance in origin stories, she added.

These quarries of a unique variety of red pipestone check all three – starting with a history of enemy tribes laying down arms to allow for quarrying, with several stories warning that if fights broke out over the rare resource, it would make itself unavailable to all.

The colorful prayer ties and flags hung from trees alongside the trails that lead around the pink and red rocks testify to the continued sacredness of the space.

“It was always a place to go pray,” said Gabrielle Drapeau, a cultural resource specialist and park ranger at the monument who started coming here as a child.

From her elders in the Yankton Sioux Tribe of South Dakota, Drapeau grew up hearing one of many origin stories for the pipestone: In time immemorial, a great flood killed most people in the area, their blood seeping into the stone and turning it red. But the Creator came, pronounced it a place of peace, and smoked a pipe, adding this is how people could reach him.

“It’s like a tangible representation of how we can connect with Creator,” Drapeau said. “All people before you are represented in the stone itself. It’s not just willy-nilly stone.”

Pipes are widely used by Indigenous people across the Great Plains and beyond, either by spiritual leaders or individuals for personal prayer for healing and thanksgiving, as well as to mark rites of passage like vision quests and the solemnity of ceremonies and gatherings.

“Pipestone has a particular relationship to our spiritual practice – praying with pipes, we take very seriously,” St. Clair said.

The pipe itself is thought to become sacred when the pipestone bowl and the wooden stem are joined. The smoke, from tobacco or prairie plants, then carries the prayer from a person’s heart to the Creator.

Because of that crucial spiritual connection, only people enrolled in federally recognized tribes can obtain permits to quarry at the monument, some traveling from as far as Montana and Nebraska. Within tribes, there’s disagreement over whether pipes should be sold, especially to non-Natives, and the pipestone used to make other art objects like carved animal figures.

“Sacredness is going to be defined by you — that’s between you and the Creator,” said Travis Erickson, a fourth-generation carver who’s worked pipestone in the area for more than two decades and embraces a less restrictive view. “Everything on this Earth is spiritual.”

His first job in the quarries, at age 10, was to break through and remove the layers of harder-than-steel quartzite covering the pipestone seam – then about six feet down, now more than 18 feet into the quarry, so the process can take months. Only hand tools can be used to avoid damaging the pipestone.

Taken out in sheets only about a couple of inches thick, it is then carved using flint and files.

“The stone talks to me,” added Erickson, who has fashioned pipe bowls in different shapes, such as horses. “Most of those pipes showed what they wanted to be.”

Growing up in the 1960s, Erickson recalled making pipes as a family affair where the day often ended with a festive grilling. He taught his children, but laments that few younger people want to take up the arduous job.

So does Pederson, some of whose younger family members have shown interest, including a granddaughter who would hang out in her workshop starting when she was 3 and emerge “pink from head to toe” from the stone dust.

But they believe the tradition will continue as long as they can share it with Native youth who might have their first encounter with this deep history on field trips to the monument.

On a recent trip, Pederson’s brother, Mark Pederson, who also holds demonstrations at the visitor center, took several young visitors into the quarries and taught them how to swing sledgehammers — and many asked to return, she said.

Teaching the techniques of quarrying and carving is crucially important, and so is helping youth develop a relationship with the pipestone and its place in the Native worldview.

“We have to be concerned with that as Dakota people – all cultural messages young people get draw away from our traditional lifeways,” St. Clair said. “We need to hold on to the teachings, prayers, songs that make pipes be.”

From new exhibits to tailored school field trips, recent initiatives at the monument — undertaken in consultation between tribal leaders and the National Park Service — are trying to foster that awareness for Native youth.

“I remind them they have every right to come here and pray,” Drapeau said — a crucial point since many Native spiritual practices were systematically repressed for decades past 1937, when the monument was created to preserve the quarries from land encroachment.

Some areas of the park are open only for ceremonial use; the 75,000 yearly visitors are asked not to interfere with the quarriers.

“The National Park Service is the newcomer here — for 3,000 years, different tribal nations have come to quarry here and developed different protocols to protect the site,” said park superintendent Lauren Blacik.

One change brought through extensive consultations with tribal leaders is the park’s decision to no longer sell pipes at the visitor center, though other pipestone objects are — like small carved turtles or owls. Pipes are available at stores a few miles away in Pipestone’s downtown.

Tensions over the use of sacred pipes by non-Natives long predates the United States, when French and English explorers traded them, said Greg Gagnon, a scholar of Indian Studies and author of a textbook on Dakota culture.

“Nobody wants to have their world appropriated. The more you open it up, the more legitimate a fear of watering it down,” he said. But there’s also a danger in becoming entrenched in dogmatic ways of understanding traditions, Gagnon added.

For carvers like Pederson, good intentions and the Spirit at work in both those practicing the craft as well as those receiving the pipestone are reasons to be optimistic about the future.

“Grandma and Grandpa always said the stone takes care of itself, knows what’s in a person’s heart,” she said.

Native American News Roundup July 9-15, 2023

Here are some of the Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Search resumes for lost cemetery at former Indian boarding school site

Archaeologists this week have been searching for the graves of former students on the grounds of the Indian Industrial School in Genoa, Nebraska.

“We’re going to take the soil down and first see if what’s showing up in the ground-penetrating radar are in fact gravelike features,” state archaeologist Dave Williams said. “And once we get that figured out, taking the feature down and determining if there are any human remains still contained within that area.”

Researchers believe more than 80 students died at the school, most from infectious diseases. So far, they’ve identified 49 students who died at the school. Some were returned home for burial, but others are believed to have been buried at the school.

The Genoa School was built in 1884 and was the fourth-largest in the federal boarding school system. It shut down in the early 1930s and today serves as a museum. The Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project has digitized many of the school’s records, which can be viewed online.

Read more:

Oglala Lakota search for truth and healing at former boarding school

Nearly 30 years ago, Justin Pourier (Oglala Lakota), then a maintenance worker at the Red Cloud Indian School on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, opened a door in the school’s oldest building and discovered a low-ceilinged room with a dirt floor.

There, he saw “three loaf-shaped dirt mounds… topped with small white, wooden crosses.”

When he told his supervisor about it, the man -- a Jesuit priest -- ordered him to stop “nosing around.” Later, workers would find the floor covered in concrete.

In 2021, after learning that the remains of more than 200 unmarked children had been found at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in Canada, Pourier decided to come forward.

The July/August 2023 issue of Wired Magazine reports on the collaboration between the school and Marsha Small, a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe with experience using ground penetrating radar to find human remains.

Red Cloud Indian School, formerly known as the Holy Rosary Mission, was founded in 1888 by the Catholic Church and ran as a boarding school until 1980.

Read more:

Read Small’s final report here:

Remains found at former Indian boarding school in Utah

A team of Utah State University anthropologists and a local historian have found and identified the graves of 12 Native American students at the site of the former Panguitch Indian School in southern Utah.

The five constituent bands making up the Paiute Indian Tribe in Utah, the Cedar Band of Paiutes, Kanosh Band of Paiutes, Koosharem Band of Paiutes, Indian Peaks Band of Paiutes and Shivwits Band of Paiutes, along with the Kaibab Band of Paiutes in nearby Arizona, expressed devastation over the find.

"Our hearts go out to the families of these children as we are left consider how best to honor and memorialize their suffering," Ona Segundo, chairwoman of the Kaibub Band of Paiute Indians, said in a statement Tuesday. "This is but the first step toward healing and reconciliation and we will, in collaboration with the descendants of those children we believe we've identified, determine what our next steps will be."

An estimated 150 students were forced to attend Panguitch during the four years it was open. The school shut down in 1909 because of “rampant illness,” Panguitch historian Steve Lee explained in 2021.

The research team has confirmed the bodies were those of two Kaibab Paiute children, four Shivwits children, and other children from other tribes.

Minnesota tribes call for reparations from university

Eleven Native American tribes have called on the University of Minnesota (UM) to make reparations for having profited from the sale of stolen Dakota and Ojibwe lands.

At the close of the U.S. Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Land Grant College Act of 1862. The law provided states with 30,000 acres of federal land for each member in their congressional delegations. States were to sell the land and use the proceeds to build and fund public colleges that would focus on agriculture and the mechanical arts.

As VOA reported in April, a three-year study of UM’s history showed the U.S. paid $2,309 for 94,631 acres of land the Dakota and Ojibwe tribes were forced to cede.

The tribes involved have not come up with a number, and university officials are considering how best to proceed.

Read more:

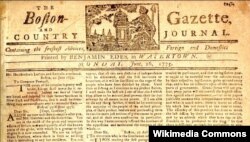

Fake News of the 18th Century: The Wampanoag uprising that wasn’t

As JSTOR’s Daily reported this week, conspiracy theories and misinformation are nothing new: In the fall of 1738, a Wampanoag woman angrily told a group of English colonists on Nantucket Island that her tribe would soon rise in rebellion and kill them all.

The men believed her and spread the news, setting off panic. Colonists launched a preemptive strike on the woman’s village, only to find all the Wampanoag sleeping peacefully.

A Boston newspaper reported the “uprising” as fact, and the story spread as far as London, even after a second newspaper, the Boston Gazette, disproved the report.

This has historians wondering whether other reported uprisings may have been exaggerated or altogether false.

Read more: