Native Americans

Dig Resumes for Children's Remains at Former Native American Boarding School in Nebraska

Archeologists resumed digging Tuesday at the remote site of a former Native American boarding school in central Nebraska, searching for the remains of children who died there decades ago.

The search for a hidden cemetery near the former Genoa Indian Industrial School in Nebraska gained renewed interest after the discovery of hundreds of children's remains at other Native American boarding school sites across the United States and Canada since 2021, said Dave Williams, the state's archeologist, whose team is digging at the site.

The team hasn't found human remains yet, Williams said, but the dig only began on Monday and is expected to last through the week.

Birds called into the sun- and wind-filled space as excavators worked within the confines of an orange fence and yellow caution tape. They sifted steadily through dirt and tossed water away while Native American leaders and community members watched intently from the sidelines.

"I came today to witness the dig because I had an aunt who died here, Mildred Lowe, in 1930, and she never came home. So, I'm here to find out if they find any bones and how we're going to go about identifying and all of that," said Carolyn Fiscus, a member of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska.

Fiscus added, "As a tribal member and elder and grandma, I'm interested. I've got a lot of spiritual and emotional investment in this. And my mom, too, who's now passed away. That's why I'm here."

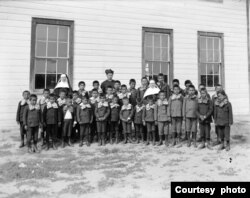

The school was part of a national system of more than 400 Native American boarding schools that attempted to assimilate Indigenous people into white culture by separating children from their families, cutting them off from their heritage and inflicting physical and emotional abuse.

Newspaper clippings, records and a student's letter indicate at least 86 students died at the school in Genoa, most due to diseases such as tuberculosis and typhoid. At least one death was blamed on an accidental shooting.

Researchers identified 49 of the children killed but have not been able to find names for 37 students. The bodies of some of those children were returned to their homes, but others are believed to have been buried on the school grounds at a location long forgotten.

Judi gaiashkibos, a member of the Ponca Tribe and the executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs, whose mother attended the school in the late 1920s, has been involved in efforts to find the cemetery for years. She said it's difficult to spend time in the community where many Native Americans suffered, but that the search can help to heal and bring the children's voices to the surface.

Williams, the archeologist, said finding the cemetery could provide some peace and comfort to people who have suffered for years, not knowing what happened to their relatives who were sent to boarding schools but never came home.

The school, about 145 kilometers west of Omaha, opened in 1884, and at its height was home to nearly 600 students from more than 40 tribes across the country. It closed in 1931, and most buildings were demolished long ago.

In an effort to find the cemetery, dogs trained to detect the odor of decaying remains searched the area last summer and indicated there could be a burial site in a narrow piece of land bordered by a farm field, railroad tracks and a canal. In November, ground-penetrating radar showed an area that was consistent with graves, but there will be no guarantees until researchers finish digging, Williams said.

The process is expected to take days.

If the dig reveals human remains, the Nebraska State Archeology Office will continue to work with the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs to decide on next steps. They could rebury the remains in the field and create a memorial or exhume and return the bodies to tribes.

Last year, the U.S. Interior Department — led by Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico and the first Native American Cabinet secretary — released a first-of-its-kind report that named hundreds of schools the federal government supported to strip Native Americans of their cultures and identities.

At least 500 children died at some of the schools, but that number is expected to reach into the thousands or tens of thousands as research continues.

"I hope they find the cemetery so that we can do ceremony and lay our spiritual relatives to rest so they know we know they're here, and they're OK," said Fiscus, of the Winnebago Tribe.

Dig Begins for Children's Remains at Defunct Native American Boarding School

In a remote patch of a long-closed Native American boarding school, near a canal and some railroad tracks, Nebraska's state archeologist and two teammates filled buckets with dirt Monday and sifted through it as if they were searching for gold.

They're trying to find the bodies of dozens of children who died at the school and have been lost for decades, a mystery that archeologists aim to unravel as they dig feet deep and meters wide in a central Nebraska field that was part of the sprawling campus a century ago.

Crews toting shovels, trowels and even smaller tools are searching the unmarked site where ground-penetrating radar suggested a possible location for the cemetery of the Genoa Indian Industrial School.

Genoa was part of a national system of more than 400 Native American boarding schools that attempted to integrate Indigenous people into white culture by separating children from their families and cutting them off from their heritage.

The school, about 90 miles (145 kilometers) west of Omaha, opened in 1884 and at its height was home to nearly 600 students from more than 40 tribes across the country. It closed in 1931 and most buildings were long ago demolished.

For decades, residents of the tiny community of Genoa, with help from Native Americans, researchers and state officials, have sought the location of a forgotten cemetery where the bodies of up to 80 students are believed to be buried.

Judi gaiashkibos, the executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs whose mother attended the school in the late 1920s, has been involved in the cemetery effort for years and planned to travel Monday to Genoa. She said it's difficult to spend time in the community where many Native Americans suffered, but the vital search can help with healing and bringing the children's voices to the surface.

"It's an honor to go on behalf of my ancestors and those who lost their lives there and I feel entrusted with a huge responsibility," gaiashkibos said.

Newspaper clippings, records and a student's letter indicate at least 86 students died at the school, usually due to diseases such as tuberculosis and typhoid, but at least one death was blamed on an accidental shooting.

Researchers identified 49 of the children killed but have not been able to find names for 37 students. The bodies of some of those children were returned to their homes but others are believed to have been buried on the school grounds at a location long ago forgotten.

As part of an effort to find the cemetery, last summer dogs trained to detect the faint odor of decaying remains searched the area and signaled they had found a burial site in a narrow piece of land bordered by a farm field, railroad tracks and a canal.

A team using ground-penetrating radar last November also showed an area that was consistent with graves, but there will be no guarantees until researchers can dig into the ground, said Dave Williams, Nebraska's state archeologist.

The process is expected to take several days.

"We're going to take the soil down and first see if what's showing up in the ground-penetrating radar are in fact grave-like features," Williams said. "And once we get that figured out, taking the feature down and determining if there are any human remains still contained within that area."

If the dig reveals human remains, the State Archeology Office will continue to work with the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs in deciding what's next. They could rebury the remains in the field and create a memorial or exhume and return the bodies to the tribes, Williams said.

DNA could indicate the region of the country each child was from but narrowing that to individual tribes would be challenging, Williams said.

The federal government is taking a closer examination of the boarding school system. The U.S. Interior Department, led by Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico and the first Native American Cabinet secretary, released an initial report in 2022 and is working on a second report with additional details.

Native American News Roundup July 2 – 8, 2023

These are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Justice Department to bolster support of regional MMIP investigations

The U.S. Justice Department has announced a new Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP) Regional Outreach Program to help prevent or respond to cases of missing and murdered Indigenous men, women and children.

DOJ will be sending five attorneys and five coordinators to offices across the U.S. to assist in investigations and promote communication and collaboration between federal, local, state and tribal police departments.

“This new program mobilizes the Justice Department’s resources to combat the crisis of Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons, which has shattered the lives of victims, their families and entire tribal communities,” Attorney General Merrick Garland said. “The Justice Department will continue to accelerate our efforts, in partnership with Tribes, to keep their communities safe and pursue justice for American Indian and Alaska Native families.”

Read more:

Chemehuevi Tribe can’t access water it’s entitled to

Two weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Navajo Nation’s bid to access water from the lower Colorado River, ProPublica reports on a California tribe’s fight to access water from the same river.

The Chemehuevi Tribe’s 13,000-hectare reservation fronts nearly 50 kilometers of the lower Colorado River in California. In 1908, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized that federally established tribes have a right to water inside or bordering their reservations; in a separate ruling in 1964, the high court gave the Chemehuevi rights to divert 11,340 acre feet (14 million cubic meters) of Colorado River water per year (AFY) — about 3.7 billion gallons.

But neither the federal government nor California has allocated funds for the tribe to build a water delivery system to access that water. Today, they rely on a single diesel pump and can access only about 307 AFY; the rest is channeled to big cities in California, including Los Angeles.

Read more:

Feds announce new online tool to support Native-owned businesses

The U.S. General Services Administration this week launched a new online search tool designed to boost the visibility of Native American-owned businesses and help them compete for government contracts.

“The Biden-Harris Administration is committed to forging cooperative relationships with Tribal Nations that are built on trust, consensus building, and shared goals – and that includes supporting the economic growth of Native-owned businesses,” GSA Administrator Robin Carnahan said. “Making it easier for buyers to obtain quality commercial products and services from Native-owned businesses is good for federal agency missions, good for the federal marketplace, and good for the communities we serve.”

The GSA is an independent federal agency that manages and supports dozens of U.S. government agencies and helps connect commercial entities with opportunities to do business with the U.S. government.

Read more:

July Fourth celebrations in small Iowa city spark big outrage

Social media users, both Native American and non-, are furious over “an egregious act of racism” that took place during a Fourth of July parade in the town of Muscatine, Iowa. It featured a woman dressed in a generic “American Indian” costume, her wrists tied, being pulled by a second woman on horseback.

The women claimed they were “paying homage” to historic injustices inflicted on the Cherokees. VOA notes that the Cherokee Nation is located 800 kilometers away in the state of Oklahoma; the Sac & Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa, the only federally recognized tribe in the state, is located just 185 kilometers away.

Sikowis Nobiss, executive director at the Great Plains Action Society, told local media the incident was offensive not just because of Natives’ historical treatment.

“We also have a very high rate of being sold and taken into the sex trafficking industry. And so, this really reminded me of … how, you know, settlers view us still. Like less than human,” Nobiss said.

Read more:

Will conservatives force well-known ice cream makers to follow their own advice?

Conservatives are calling for a boycott of America’s biggest ice cream manufacturer for calling on Americans to return land stolen from Native Americans, beginning with Mount Rushmore in South Dakota.

“On the Fourth of July, many people in the U.S. celebrate liberty and independence — our country’s and our own,” the company posted on its website. “But what is the meaning of Independence Day for those whose land this country stole, those who were murdered and forced with brutal violence onto reservations, those who were pushed from their holy places and denied their freedom?”

South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem told Fox News she wasn’t going to listen to “a bunch of liberal Vermont businessmen who think they know everything about this country and haven’t studied our history.”

Ben and Jerry’s explained that history on their website Tuesday:

“In 1970, Indigenous activists climbed Mount Rushmore and occupied it for months, demanding that land be returned to the Sioux,” the notice reads. “Ten years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Mount Rushmore and the Black Hills had indeed been stolen … and awarded the Sioux $105 million in damages, but the tribes refused the payment.”

As Newsweek noted this week, “Some have argued that Ben & Jerry's Vermont headquarters is itself built on what it describes as ‘stolen’ land of the Abenaki tribe — prompting questions as to whether it would give the property up and move elsewhere,”

Even some Native Americans took issue with Ben and Jerry’s call to action:

Read more:

Native American News Roundup June 25 - July 1, 2023

SCOTUS Ruling on Navajo Water Rights—Where Does This Leave the Tribe?

This week, VOA looks at the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 22 ruling in Arizona v. Navajo Nation, a case that examined whether the U.S. government has a treaty obligation to help Navajo access Colorado River water.

The conflict

The Colorado River system supplies nearly 40 million people with drinking water and irrigates more than 5 million acres of farmland in the Rocky Mountains and Southwest United States.

But climate change has contributed to decades of drought, and water levels in the Colorado River have dropped alarmingly.

For the Navajo Nation, the crisis is acute. A third of the 175,000 Navajo living on the reservation lack access to clean water and must have it delivered by truck or drive miles to haul it themselves. The Navajos want access to the lower Colorado River flowing just outside the reservation’s northwestern border.

“The bottom line is that the treaties and their promises mean what the Navajos reasonably understood them to mean,” their lawyers argued before the Supreme Court. “When it signed the 1868 Treaty, the United States knew that water access was crucial to the survival of Indians living in the Colorado River Basin.”

States in the region, however, argued otherwise, worrying that ruling in favor of the Navajo would further strain “a river system already stretched beyond its capacity,” and threaten an agricultural industry that supplies much of the nation.

History

In late 1863, the U.S. Army began capturing groups of Navajo from their traditional homelands in the Four Corners region of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Colorado and forcing them along the more than 300-mile “Long Walk” to the Bosque Redondo reservation along the Pecos River in New Mexico. Several hundred died or were killed along the way; 8,000 survived the march.

The Army intended to make self-sufficient farmers out of the prisoners. But the land was unsuitable for farming, the water was unfit to drink and firewood was scarce. Two thousand or more died of exposure, starvation or contagious disease.

But it was the “great expense” of feeding and clothing survivors that drove the government to draw up a treaty and return them to a small portion of their original homelands.

The government promised to build schools and a church, where timber and water were convenient; supply seeds and farming tools; and provide money to buy sheep, goats and cows. The treaty made no other mention of water, but as contemporary observers have noted, Navajos at the time would have assumed the government would make sure they had enough water to sustain themselves.

In last week’s decision, Justice Brett Kavanaugh cited a 1908 SCOTUS ruling establishing tribes’ rights to waters that “arise, border, cross, underlie or are encompassed within reservations.”

He ruled that the court has no legal obligation to take steps to identify or secure the reservation’s water needs.

“The historical record does not suggest that the United States agreed to undertake affirmative efforts to secure water for the Navajos -- any more than … [it] agreed to farm land, mine minerals, harvest timber, build roads or construct bridges on the reservation,” Kavanaugh wrote.

That said, he pointed out that Congress and the president are empowered to enact laws that might help the Navajo with their water needs.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Neil Gorsuch said that the Navajo “ask” was simple: “They want the United States to identify the water rights it holds for them,” he wrote. “And if the United States has misappropriated the Navajo’s water rights, the Tribe asks it to formulate a plan to stop doing so prospectively.”

Mixed reactions

ProPublica quotes the Arizona Department of Water Resources as being “grateful” for the ruling “because it did not disrupt how the Colorado River system is managed.”

But tribes in the region condemned the judgement.

“The Supreme Court got it wrong with their decision last week,” Native News Online editor Levi Rickert wrote in an editorial Monday. “Given history, I should have seen it coming.”

In the same edition, longtime Navajo activist and spiritual adviser Lenny Foster called the ruling “an abomination and a supreme insult and long-term mistake.”

Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren, voted into office in November 2022 on promises to secure the “basic necessities for every Navajo home,” said the fight for water rights isn’t over.

Looking forward, the Navajo have the options of continuing long-standing -- and, so far unsuccessful -- negotiations with the state of Arizona, or, as Justice Gorsuch suggested, of intervening in other court cases that “affect their claimed interests” in water rights.

Native American News Roundup June 18-24, 2023

Supreme Court Upholds Indian Child Welfare Act--For Now

The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Haaland v. Brackeen upholding the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) reinforces tribal sovereignty, but some Native American leaders worry the legal challenges there are not over.

Congress passed ICWA in 1978 to stop state welfare systems from placing Native American children in non-Native families, a practice that Native Americans viewed as a continuation of historic federal efforts to "civilize" and assimilate Indians. Among other provisions, ICWA requires states to make every effort to place children in Native American homes.

In 2017, Texas couple Chad and Jennifer Brackeen and two other sets of non-Native foster parents looking to adopt Native children took the U.S. government to court, arguing — in part — that ICWA is unconstitutional because it discriminates on the basis of race.

A U.S. judge initially ruled in their favor. That was overturned on appeal on the grounds that Native Americans are a political group, not a race. The conservative libertarian group the Goldwater Institute and two other groups then took the case to the Supreme Court.

As Justices readied to hear arguments in November 2022, Goldwater litigator Timothy Sandefur explained to VOA why the group opposes the law.

"Part of the problem with ICWA is that it … deprives states of the ability to protect Native children against abuse and, in fact, forces states to send Indian children back to abused homes that are known to be dangerous, where they are exposed to further harm," Sandefur said.

He cited three cases in which Indian children in foster care were returned to abusive families and killed. Among them was 5-year-old Antonio Renova, who was beaten to death by his biological parents 18 months after a Crow Tribe judge ordered his foster parents to return him to his biological parents.

Plaintiffs argued that Congress is "commandeering" states into enforcing federal law, in violation of the U.S. Constitution. And that gets at the heart of what's really driving ICWA detractors, said Sydney Tarzwell, an attorney with the Native American Rights Fund.

"I do not see Tim Sandefur, Goldwater or any of the other organizations involved in this case actively engaging in conversations centered in child welfare best practices and what actually works," she told VOA. "Tearing down federal Indian law via ICWA would serve their other interests."

Some environmental groups such as the nonprofit Accountable.US have suggested that Goldwater and allies with close ties to the fossil fuel industry are looking to erode tribal sovereignty on matters of resource extraction on public lands.

"That's my favorite conspiracy theory," Sandefur said. "It's ridiculous — but I don't know how to deny it."

The Court speaks

For now, tribal sovereignty in welfare matters is reaffirmed.

"Under our Constitution, Tribes remain independent sovereigns responsible for governing their own affairs," Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote for the Court majority. "In adopting the Indian Child Welfare Act, Congress exercised that lawful authority to secure the right of Indian parents to raise their families as they please; the right of Indian children to grow in their culture; and the right of Indian communities to resist fading into the twilight of history."

Sandefur notes that ICWA lawsuits are still pending in several states, including California.

"The Supreme Court chose not to decide the constitutionality of ICWA as far as its racially discriminatory provisions are concerned," he said. "What that means is that someday the Court will be forced to resolve whether Indian children can be relegated to second class status and stripped of their constitutional rights based on their race."

Erin Dougherty Lynch, managing attorney for the Native American Rights Fund in Anchorage, says Sandefur is probably right.

"Regardless of what happened in Brackeen, they [ICWA detractors] are going to keep bringing in cases," she told VOA. "I don't mean to put too fine a point on it, but these are people who, in my opinion, are not accustomed to losing. They're not accustomed to being told no. They're very accustomed to getting what they want."

U.S. President Joe Biden said the nation's "painful history" loomed large over the Brackeen decision.

"In the not-so-distant past, Native children were stolen from the arms of the people who loved them. They were sent to boarding schools or to be raised by non-Indian families — all with the aim of erasing who they are as Native people and tribal citizens," he said in a statement.

"These were acts of unspeakable cruelty that affected generations of Native children and threatened the very survival of Tribal Nations. The Indian Child Welfare Act was our Nation's promise: never again."

Supreme Court Rejects Challenge to Native American Child Welfare Law

The Supreme Court on Thursday preserved the system that gives preference to Native American families in foster care and adoption proceedings of Native children, rejecting a broad attack from Republican-led states and white families who argued it is based on race.

The court left in place the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act, which was enacted to address concerns that Native children were being separated from their families and, too frequently, placed in non-Native homes.

Tribal leaders have backed the law as a means of preserving their families, traditions and cultures.

The "issues are complicated" Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote for a seven-justice majority, but the "bottom line is that we reject all of petitioners' challenges to the statute."

Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas dissented.

Congress passed the law in response to the alarming rate at which Native American and Alaska Native children were taken from their homes by public and private agencies.

The law requires states to notify tribes and seek placement with the child's extended family, members of the child's tribe or other Native American families.

Three white families, the state of Texas and a small number of other states claim the law is based on race and is unconstitutional under the equal protection clause. They also contend it puts the interests of tribes ahead of children and improperly allows the federal government too much power over adoptions and foster placements, areas that typically are under state control.

The lead plaintiffs in the Supreme Court case — Chad and Jennifer Brackeen of Fort Worth, Texas — adopted a Native American child after a prolonged legal fight with the Navajo Nation, one of the two largest Native American tribes, based in the Southwest. The Brackeens are trying to adopt the boy's half-sister, now 4, who has lived with them since infancy. The Navajo Nation has opposed that adoption.

More than three-quarters of the 574 federally recognized tribes in the country and nearly two dozen state attorneys general across the political spectrum had called on the high court to uphold the law.

All the children who have been involved in the current case at one point are enrolled or could be enrolled as Navajo, Cherokee, White Earth Band of Ojibwe and Ysleta del Sur Pueblo. Some of the adoptions have been finalized while some are still being challenged.

The high court had twice taken up cases on the Indian Child Welfare Act before, in 1989 and in 2013, that have stirred immense emotion.

Before the Indian Child Welfare Act was enacted, between 25% and 35% of Native American children were being taken from their homes and placed with adoptive families, in foster care or in institutions. Most were placed with white families or in boarding schools in attempts to assimilate them.

Native American News Roundup May 28-June 3, 2023

Here are some of the Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Tribes fear pending Supreme Court ruling could upend sovereignty

Native Americans are watching the U.S. Supreme Court for a decision in the case Brackeen v. Haaland, which will decide the fate of the 40-year-old Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA).

Congress passed ICWA in 1978 to stop the large-scale removal of Indian children from their families and their placement in non-Native homes, as this was widely viewed as an attack on tribal sovereignty and a continuation of federal assimilation policies.

Ahead of ICWA’s passage, Calvin Isaac, former chief of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw who died in 2020, argued before the House Subcommittee on Indian Affairs that “many of the individuals who decide the fate of our children are, at best, ignorant of our cultural values and at worst, have contempt for the Indian way and convinced that removal, usually to a non-Indian household or institution, can only benefit an Indian child.”

In 2016, three sets of non-Native foster and prospective adoptive parents, along with the states of Texas, Indiana and Louisiana, took the federal government to court, arguing that the law discriminates based on race and that child welfare should be a matter for states and not the federal government to decide.

The Supreme Court heard arguments in the case last November and is expected to rule in the coming weeks.

Read more:

Remembering fallen Native American service members

May 29 was Memorial Day, a day to remember those Americans who have died serving their country.

Levi Rickert, a citizen of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation in Kansas and founder/editor of Native News Online, marked the occasion by reflecting on Native Americans’ long and proud tradition of military service.

Among those who have paid the ultimate price is U.S. Army Specialist Lori Ann Piestewa, a citizen of the Hopi Nation, who died when her convoy was ambushed in Nasiriyah, Iraq, on March 23, 2003. She is remembered as the first female soldier to die in Iraq and the first Native American woman to die serving her country.

Native Americans and/or Alaska Natives have served in every U.S. war and conflict since the American Revolution, and as Rickert notes, have the highest record of military service per capita of any other racial or ethnic group in the U.S.

Read more:

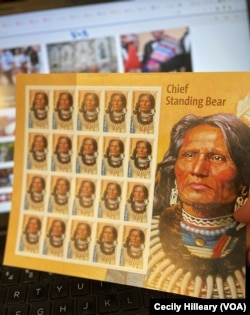

U.S. Postal Service commemorates legendary Ponca leader

The U.S. Postal Service has released a postage stamp honoring Ponca Tribe Chief Standing Bear, one of the nation’s most important civil rights figures.

He saw his tribe through their forced removal in 1877 from homelands in Nebraska to Indian Country [present-day Oklahoma]. His daughter Prairie Flower died along the way, and within a year, a third of the tribe died of disease and starvation, including his son Bear Shield, whose dying wish was to be buried back home.

Standing Bear honored that wish but was arrested for leaving Oklahoma. He sued the federal government for his freedom, arguing before the court, “I am a man. The same God made us both."

In a landmark ruling on May 12, 1879, Judge Elmer S. Dundy declared for the first time that an Indian was a person within the meaning of U.S. law and therefore deserved all legal protections.

Learn more in the video below:

Indian? Native American? What to call America’s first peoples?

Oklahoma TV station KSWO this week posed that question to two tribal leaders.

“There’s a lot of terms that have been bounced around, and you’ll never find any universal acceptance from that from anybody because it’s just too complex,” Kiowa Tribe Chairman Lawrence SpottedBird said.

Comanche Nation Vice Chairman Dr. Cornel Pewewardy said he prefers Nʉmʉnʉʉ “the People,” which is what the Comanche people have always called themselves.

But how to refer to America’s original populations generally?

“Indian” was the name that explorer Christopher Columbus gave the people he encountered, assuming he had landed in India. Many Native Americans continue to use the term, as it was the legal term used in treaties with the federal government.

“Indigenous” is a word with different definitions. For some, it refers to an ethnic culture that has never migrated away from its homeland and is neither a settler nor a colonizer.

The United Nations defines “Indigenous” as the descendants of those who inhabited a country or region at the time of conquest or colonization by another group.

And some tribes find the term offensive, believing it carries negative implications.

Several years ago, VOA asked Chase Iron Eyes, a Hunkpapa Lakota activist from the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota.

“Call me whatever you want, as long as you do it with respect,” he answered.

See more:

Native American News Roundup May 21-27, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Deb Haaland hears from Northern Arizona tribes

Deb Haaland on Monday became the first U.S. Secretary of the Interior to visit Supai, a remote Havasupai village at the bottom of the Grand Canyon that can only be reached on foot, by horseback or by helicopter.

She was there to discuss plans to connect more than 100 homes and other Havasupai institutions to broadband internet, a project made possible by more than $7 million in Bipartisan Infrastructure Act funding.

It was part of a three-day visit to Arizona that included meeting with tribal leaders and environmental groups hoping the Biden administration will designate more than 400,000 hectares of land surrounding the Grand Canyon as a national monument.

Haaland also met with Hopi tribal leaders, announcing $6.6 million in federal infrastructure funding to replace an arsenic-contaminated water system in Keams Canyon, Arizona.

Read more:

‘Pretendian’ Seattle artist sentenced for violating Indian Arts and Crafts Act

A federal judge on Wednesday sentenced a Seattle artist to 18 months’ probation for violating the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, a law designed to stop the counterfeiting of Native American art.

Prosecutors say 67-year-old Jerry Chris Van Dyke falsely claimed to be a member of the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho for 10 years, carving and selling more than $1,000 worth of Aleut-style pendants.

“Prosecuting cases of fraud in the art world is a unique responsibility and part of our work to support Tribal Nations,” said U.S. Attorney Nick Brown. “I hope this case will make artists and gallery owners think twice about the consequences of falsely calling an artist Native and work Native-produced.”

Read more:

US Border Patrol shoots, kills, Tohono O’odham Tribe member

Family, friends and investigators are demanding answers after U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents shot dead a member of the Tohono O’odham Nation outside of his home in the Menagers Dam community near the U.S.-Mexico border.

An unnamed family member told Tucson’s KVOA TV that ceremony leader Raymond Mattia had called CBP for help, complaining that illegal immigrants had trespassed onto his property.

What happened next is unclear: Family members told the television station that CBP agents opened fire on Mattia as he stood outside his front door.

“Raymond lay in front of his home for seven hours before a coroner arrived from Tucson,” his family said in a statement posted online early Thursday morning.

A CBP statement says agents from the Ajo Border Patrol Station responded to a Tohono O’odham Nation Police Department request for assistance in responding to a call of shots fired west of the Menagers Dam Village. There, the statement says, an individual “threw an object toward the officer as they approached the structure which landed a few feet from the officer’s feet. Shortly after the individual threw the object, he abruptly extended his right arm away from his body and three agents fired their service weapons striking the individual several times.”

The CBP statement says officers requested emergency medical services and that the man was pronounced dead by a physician at St. Mary’s Hospital at 10:06 pm.

The Tohono O’odham Nation, the second-largest reservation in the U.S., straddles the border with Mexico. Tribe members have long complained of aggression and other abuses committed by agents operating in the area. Tribal police and the FBI are looking into the matter.

Historian: Was poisoning of Pamunkey Indians North America’s first war crime?

Smithsonian magazine this week recalls a grim chapter in U.S. colonial history. University of Southern California historian Peter C. Mancall writes about the Second Anglo-European War in which Powhatan Confederacy leader Opechancanough launched a set of surprise attacks on more than 30 English settlements in March 1622, killing nearly 350 settlers.

During the following months, English settlers repeatedly attacked tribal villages, burning crops and stealing food.

In May 1623, British soldiers met with Opechancanough in West Point, Virginia, supposedly to negotiate the release of war prisoners. Instead, they served poisoned wine to about 200 Indians. It is not known how many died; Opechancanough escaped the scene but was later captured and killed.

Read more:

Google Doodle celebrates photographer, writer and Native activist Barbara May Cameron

Google Doodle this week honored Hunkpapa Lakota photographer, poet, writer and human rights activist Barbara May Cameron, who would have turned 69 on Monday.

Raised on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, Cameron studied photography and film at the American Indian Art Institute in Santa Fe, New Mexico. In 1973, she moved to San Francisco, where she co-founded Gay American Indians, the first group ever dedicated to the rights of LGBTQIA+ Native Americans.

Cameron was also active with the San Francisco AIDS Foundation and the American Indian AIDS Institute, and she served as a consultant to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, helping with AIDS and childhood immunization programs.

Cameron died in 2002 at age 47.

Read more:

New Mexican Spanish, a Unique American Dialect, Survives Mostly in Prayers

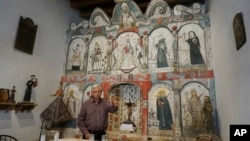

On a spring Saturday afternoon, two "hermanos" knelt to pray in the chapel of their Catholic brotherhood of St. Isidore the Farmer, nestled by the pine forest outside this hamlet in a high mountain valley.

Fidel Trujillo and Leo Paul Pacheco's words resounded in New Mexican Spanish, a unique dialect that evolved through the mixing of medieval Spanish and Indigenous forms. The historic, endangered dialect is as central to these communities as their iconic adobe churches, and its best chance of survival might be through faith, too.

"Prayers sung or recited are our sacred heritage," said Gabriel Meléndez, a professor emeritus of American Studies with the University of New Mexico who's also a hermano. "When prayers are said in Spanish, they're stronger. They connect us directly to people who came before us."

Preserved mostly in devotions, particularly in humble "moradas" – as the brotherhoods' chapels are called – built of mud and straw in rural communities across the northern reaches of the state, New Mexican Spanish is different from all other varieties of the language.

"Unlike most other forms of Spanish used in the U.S. today, it's not due to immigration in the last 100 years, but rooted back to the 1500s," said Israel Sanz-Sánchez, a professor of languages at West Chester University in Pennsylvania who has researched the dialect.

Spanish explorers and missionaries first reached these valleys isolated between mountains, deserts and plains at the end of the 16th century. Pushed back south by the Pueblo Native Americans, they resettled a century later – and their language evolved to incorporate not only words carried from medieval Spain but also a mixture of expressions derived from Mexican Spanish, Native forms and eventually some English after the territory became part of the United States.

Removed from the center of political and economic power for centuries, these villages preserved the dialect orally.

"You never heard English here," said Felix López of growing up in the 1950s in Truchas, a ridgetop village between Santa Fe and Taos, where this master "santero" – an artist specializing in devotional art – has been helping preserve the 1760s Holy Mission church.

But by the mid-20th century, the push to promote schooling in English led many educators to correct students who used New Mexican Spanish's idiosyncratic mix of grammar, pronunciation and vocabulary, said Damián Vergara Wilson, a professor of Spanish at the University of New Mexico.

He has been working on teaching Spanish not as foreign but as a heritage language that has developed into something uniquely New Mexican.

It contains some words from medieval Spanish, but it also includes pronunciations that developed in New Mexico's villages and words unique to its geographical and historical place at a crossroads of American civilizations. There are several words for turkey, for instance, including an anglicized one used in the context of Thanksgiving.

With such code-switching sometimes disparaged in education and among the public, younger generations often stick to English only or learn contemporary Spanish, especially as spoken in Mexico, with which the state shares a border. That leads many villagers to worry about being able to preserve New Mexican Spanish.

"The dialect we speak is dying out. We're the last generation that learned it as a first language," said Angelo Sandoval, 45, who serves as the "mayordomo" or caretaker of the 1830s San Antonio Church in Cordova, a village just down the valley from Truchas.

Its best chance for survival is prayer. Traditional devotions have been passed down through generations by hermanos, easily memorized because of their ballad-style rhyming. Sometimes they are transcribed into notebooks called "cuadernos." In an adobe niche in a chapel in Holman, some of the handwritten notebooks are 120 years old.

Even in larger cities, people often request prayers in New Mexican Spanish for special occasions, like rosaries for the deceased or novenas for the holidays.

In Santa Fe, the prayer to the widely venerated statue of Our Lady of Peace contains some of the original Spanish terminology, such as "Sacratisimo Hijo" for the "most holy Son," said Bernadette Lucero, director, curator and archivist for the Archdiocese of Santa Fe.

A nearly century-old women's folklore society — Sociedad Folklórica de Nuevo México — also regularly practices the dialect for their hymns and nine-day "novenas" prayers to baby Jesus, Lucero added.

In the small town of Bernalillo, where the outskirts of Albuquerque fade into vast mesas, the mayordomos of San Lorenzo also preserve the dialect in their prayers and annual celebrations.

"When we sing an old 'alabado,' we can trace who wrote that," said Santiago Montoya of the Catholic praise (in Spanish, "alabar") hymns that have been passed down through New Mexican brotherhoods.

For 23 years, Montoya and his sister have been the mayordomos of San Lorenzo, a church that was constructed in the mid-19th century with 4-foot-wide adobe walls. The community fought to save it when a bigger, modern church was built next door.

But he's also a "rezador," reciting or singing the rosary — a prayer consisting of sets of Hail Marys called "decades" — which he does in the community and particularly for the deceased. He insists on using New Mexican Spanish even if the families speak only English.

"I tell them, 'I'll do three 'decades' in English, but let's teach the kids,'" Montoya said.

In Cannes, Scorsese and Dicaprio Turn Spotlight Toward Osage Nation

It was well into the process of making "Killers of the Flower Moon" that Martin Scorsese realized it wasn't a detective story.

Scorsese, actor Leonardo DiCaprio and screenwriter Eric Roth had many potential avenues in adapting David Grann's expansive nonfiction history, "Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI." The film that Scorsese and company premiered Saturday at the Cannes Film Festival, however, wasn't like the one they initially set out to make.

The film, which will open in theaters in October, chronicles the series of killings that took place throughout the Osage Nation in 1920s Oklahoma. The Osage were then enormously rich from oil on their land, and many white barons and gangsters alike sought to control and steal their money. Dozens of Osage Native Americans were killed before the FBI, in its infancy, began to investigate.

DiCaprio had originally been cast to star as FBI agent Tom White. But after mulling the project over, Scorsese decided to pivot.

"I said, 'I think the audience is ahead of us,’" Scorsese told reporters Sunday in Cannes. "They know it's not a whodunit. It's a who-didn't-do-it."

The shift, filmmakers said, was largely driven from collaboration with the Osage. Osage Nation Chief Standing Bear, who consulted on the film, praised the filmmakers for centering the story instead on Mollie (Lily Gladstone) and her husband Ernest Burkhart (DiCaprio), the tragic romance at the heart of Scorsese's epic of insidious American ethnic exploitation.

"Early on, I asked Mr. Scorsese, 'How are you going to approach the story? He said I'm going to tell a story about trust, trust between Mollie and Ernest, trust between the outside world and the Osage, and the betrayal of those trusts," said Chief Standing Bear. "My people suffered greatly and to this very day those effects are with us. But I can say on behalf of the Osage, Marty Scorsese and his team have restored trust and we know that trust will not be betrayed."

"Killers of the Flower Moon," the most anticipated film to debut at this year's Cannes, instead became about Ernest, who Scorsese called "the character the least is written about."

DiCaprio, who ceded the character of White to Jesse Plemons, said "Killers of the Flower Moon" reverberates with other only recently widely discussed dark chapters of American history.

"This story, much like the Tulsa massacre, has been something that people have started to learn about and started to understand is part of culture, part of our history," said DiCaprio. "After the screenplay, from almost an anthropological perspective — Marty was there every day — we were talking to the community, trying to hear the real stories and trying to incorporate the truth."

"Killers of the Flower Moon" premiered Saturday to largely rave reviews and thunderous applause nearly 50 years after Scorsese, as a young filmmaker, was a sensation at Cannes. His "Taxi Driver" won the Palme d'Or in 1976.

Among the most-praised performances has been that of Gladstone, the actor of Blackfeet and Nimíipuu heritage.

"These artistic souls on this stage here cared about telling a story that pierces the veil of what society tells us we're supposed to care about and not," said Gladstone, who singled out Scorsese. "Who else is going to challenge people to challenge their own complicity in white supremacy in such a platform except as this man here?"

"We're speaking of the 1920s Osage community. We're talking about Black Wall Street and Tulsa. We're talking about a lot in our film," she continued. "Why the hell does the world not know about these things? Our communities always have. It's so central to everything about how we understand our place in the world."

In the film, Robert De Niro plays a wealthy baron who's particularly adept at plundering the Osage. Speaking Sunday, De Niro was still mulling his character's motivations.

"There's a kind of feeling of entitlement," said De Niro. "It's the banality of evil. It's the thing that we have to watch out for. We see it today, of course. We all know who I'm going to talk about, but I won't say the name. Because that guy is stupid. Imagine if you're smart?"

A minute later, De Niro resumed: "I mean, look at Trump," referring to former President Donald Trump.

With a running time well over three hours and a budget from Apple of $200 million, "Killers of the Flower Moon" is one of Scorsese's largest undertakings. Asked where he gets the gumption for such risks, the 80-year-old director didn't hesitate.

"As far as taking risks at this age, what else can I do?" said Scorsese. "‘No, let's go do something comfortable.’ Are you kidding?"

At Graduations, Native American Students Seek Acceptance of Tribal Regalia

Yanchick settled for beaded earrings to represent her Native American identity at her 2018 graduation.

A bill vetoed earlier this month by Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, would have allowed public school students to wear feathers, beaded caps, stoles or other objects of cultural and religious significance. Yanchick, a citizen of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and descendent of the Muscogee Nation, said she hopes the legislature tries again.

Being able to "unapologetically express yourself and take pride in your culture at a celebration without having to ask a non-Native person for permission to do so is really significant," said Yanchick, who now works for the American Civil Liberties Union of Oklahoma.

For Native American students, tribal regalia is often passed down through generations and worn at graduations to signify connection with the community. Disputes over such attire have spurred laws making it illegal to prevent Indigenous students from wearing regalia in nearly a dozen states including Arizona, Oregon, South Dakota, North Dakota and Washington.

High schools, which often favor uniformity at commencement ceremonies, take a range of approaches toward policing sashes, flower leis and other forms of self-expression. Advocates argue the laws are needed to avoid leaving it up to individual administrators.

Groups like the Native American Rights Fund hear regularly from students blocked from wearing eagle feathers or other regalia. This week in Oklahoma, a Native American high school graduate sued a school district, claiming she was forced her to remove a feather from her cap at a ceremony last spring.

When Jade Roberson graduated from Edmond Santa Fe High School, the same school attended by Yanchick, she would have liked to wear a beaded cap and a large turquoise necklace above her gown. But it didn't seem worth asking. She said a friend was only able to wear an eagle feather because he spoke with several counselors, consulted the principal and received a letter from the Cherokee Nation on the feather's significance.

"It was such a hassle for him that my friends and I decided to just wear things under our gown," said Roberson, who is of Navajo descent. "I think it is such a metaphor for what it is like to be Native."

When Adriana Redbird graduates this week from Sovereign Community School, a charter school in Oklahoma City that allows regalia, she plans to wear a beaded cap and feather given by her father to signify her achievements.

"To pay tribute and take a small part of our culture and bring that with us on graduation day is meaningful," she said.

In his veto message, Stitt said allowing students to wear tribal regalia should be up to individual districts. He said the proposal could also lead other groups to "demand special favor to wear whatever they please" at graduations.

The bill's author, Republican state Rep. Trey Caldwell, represents a district in southwest Oklahoma that includes lands once controlled by Kiowa, Apache and Comanche tribes.

"It's just the right thing to do, especially with so much of Native American culture so centered around right of passage, becoming a man, becoming an adult," he said.

Several tribal nations have called for an override of the veto. Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin said the bill would have helped foster a sense of pride among Native American students. Muscogee Nation Principal Chief David Hill said students who "choose to express the culture and heritage of their respective Nations" are honoring their identity.

It means a lot that the bill was able to garner support and make it to the governor, Yanchick said, but she wishes it wasn't so controversial.

"Native American students shouldn't have to be forced to be activists to express themselves or feel celebrated," she said.

Native American News Roundup May 7-13, 2023

California professor confesses she is ‘a white person,’ not Native

Native Americans and non-Native allies are expressing outrage over a University of California Berkeley professor who has admitted she has no Mohawk or Mi’kmaq ancestry.

Associate professor Elizabeth Hoover posted a “Letter of Accountability and Apology” on her website Monday, admitting she is "a white person who has incorrectly identified as Native" her entire life.

She said she did not knowingly falsify her heritage but relied on family lore which she did not try to verify until 2022, when questions were raised about her identity.

“I have brought hurt, harm, and broken trust to the Native community at large, and to specific Native communities I have worked with and lived alongside, and for that, I am deeply sorry,” Hoover stated.

More than 380 students and educators have signed a statement calling for Hoover to resign from “all positions on boards and advisory committees and all grants, speaking engagements, and other paid opportunities she obtained with her false identity.”

UC Berkeley spokesperson Janet Gilmore did not comment on what, if any, disciplinary action the university would take.

As VOA previously reported, Native and First Nations scholars say colleges and universities are “overrun” by academicians who falsely claim Indigenous identity. They not only rob legitimate Indigenous scholars of opportunities but inform public policy.

Read more:

Study: Early humans in North America migrated from China

New research from China suggests that some ancient humans migrated to the Americas from northern coastal China in the region of the Bohai and Yellow seas.

Scientists examined modern and ancient mitochondrial DNA to trace a rare female lineage. They found 216 modern-day and 39 ancient individuals who share that prehistoric ancestry.

“In addition to previously described ancestral sources in Siberia, Australo-Melanesia, and Southeast Asia, we show that northern coastal China also contributed to the gene pool of Native Americans,” Yu-Chin Li, a molecular anthropologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said in a statement.

The research published this week in Cell Reports shows two separate migrations between China, Japan and North America during and after the Ice Age. Researchers say this would explain similarities between prehistoric arrowheads and spearheads found in China, Japan and the Americas.

Read more:

Catholic groups ran nearly 90 Indian boarding schools in US

An independent collaboration of native tribe and Catholic Church members, historians and archivists this week published a list of Indian boarding schools that were run by the Catholic Church.

The Catholic Native Boarding School Accountability and Healing Project published an online list showing that Catholic dioceses, parishes and religious orders established and operated schools across 22 states; the majority were run by Catholic sisters representing 53 religious orders.

“We are under no pretense that our list is complete,” the group said. “We have done our best to offer the most accurate information possible, but we also anticipate future revisions as additional information is obtained.”

The list expands and corrects a May 2022 U.S. Interior Department report that followed a nine-month probe into federal Indian boarding schools.

The federal government once regarded Christianization to be key to assimilating Native Americans into mainstream American society. The Catholic Church was one of more than 14 denominations of Christians that ran Indian boarding schools between the 1820s and 1970s.

Read more:

Alaska Federation of Native loses two of its largest members

The Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) lost two members this week, sparking concerns about the future of an organization that represents the interests of more than 200 tribes and corporations in Alaska.

The Central Council of the Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, the largest federally recognized tribe in the state, announced Monday it would withdraw from the federation and pursue its political interests independently.

“The truth of the matter is our Executive Council has diverse areas of expertise and this has been a true strength in the governance of our Tribe,” Tlingit and Haida President Richard Chalyee Eesh Peterson said in a written statement Monday.

Separately, the Tanana Chiefs Conference (TCC) also decided to quit the AFN.

“Over the past few years, over 40 resolutions were passed by the full board at AFN that support a subsistence way of life, but no significant action has been taken on those directives,” the group said on its website.

TCC represents 39 villages and 37 federally recognized tribes across more than 608,000 square kilometers (235,000 square miles).

Since 2019, five organizations have withdrawn their AFN memberships.

Read more:

Native American News Roundup April 30-May 6, 2023

Here are some of Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Oklahoma’s Cherokee governor vetoes Native regalia bill

Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt this week vetoed a bill that would have allowed Native American students to wear tribal regalia during graduation ceremonies.

Senate Bill 429, which passed both the Oklahoma House and Senate, defined regalia as clothing, jewelry, feathers, stoles and “similar objects of cultural and religious significance.”

Stitt, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation whose ancestry has been previously challenged, vetoed the bill on Monday, saying schools had the right to determine their own dress codes.

“In other words, if schools want to allow their students to wear tribal regalia at graduation, good on them; but if schools prefer for their students to wear only traditional cap and gown, the Legislature shouldn’t stand in their way,” he said in his veto message.

Native American Rights Fund Deputy Director Matthew Campbell said that wearing feathers and regalia is “already a protected religious freedom for Native students.”

He added, “Unfortunately, Governor Stitt’s veto sends a message to Native students that in Oklahoma, Native students must choose between their culture and religious freedoms and celebrating their achievements.”

Cherokee Principal Chief Chuck Hoskins joined Choctaw Nation Chief Gary Batton in urging lawmakers to “quickly override” the veto.

Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act

The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 included a provision allowing “special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction” (SDVCJ) over non-Indian offenders committing domestic violence or dating violence on tribal land. Prior to this, tribes did not have jurisdiction over non-Native offenders on tribal lands.

Currently, more than 30 tribes exercise SDVCJ, and under the 2022 reauthorization of the act, can now be reimbursed for the costs involved in prosecuting these cases.

That reauthorization, also known as VAWA 2022, expanded the types of cases these tribes may prosecute to include sexual violence, sex trafficking, stalking, child violence, assault of tribal justice personnel and obstruction of justice.

“Tribes know best what their communities need, so I encourage tribal leaders, community members, and survivors to review this regulation for the Tribal Jurisdiction Reimbursement Program. It is critical that programs serving tribal communities are informed by tribal voices,” said Allison Randall, acting director of the Justice Department’s Office of Violence Against Women

“We are dedicated to removing barriers to access, and it is a victory that VAWA 2022 allows us to continue the Tribal Jurisdiction Program, as well as reimburse expenses incurred as a result of implementation.”

The interim final rule on reimbursements was published April 11. The public has until June 12 to comment.

Read more:

Navajo Nation rejects Biden proposed ban on mineral leasing near Chaco

The Navajo Nation this week approved a resolution opposing the Biden administration’s proposed ban on oil and gas drilling on federal lands in and around New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon.

U.S. Interior Department Secretary Deb Haaland announced in November 2022 a 20-year moratorium on mineral leasing within a 16-kilometer buffer zone around the site.

“Chaco Canyon is a sacred place that holds deep meaning for the Indigenous peoples whose ancestors lived, worked and thrived in that high desert community,” Haaland said at the time. “Now is the time to consider more enduring protections … so that we can pass on this rich cultural legacy to future generations.”

Navajo leadership opposes the plan, cautioning President Biden that it could have a “devastating impact” on thousands of Navajo land allottees who depend on oil and gas royalties for their livelihoods. At the time, the Nation suggested reducing the buffer zone around the canyon to 8 kilometers. The resolution signed this week opposes any buffer zone whatsoever.

Quannah Chasinghorse at 2023 Met Gala

Han Gwich’in and Oglala Lakota activist and model Quannah Chasinghorse was among the celebrities wearing pink at this year’s Metropolitan Museum of Art gala on Monday, which honored controversial fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld who died in 2019. Many media outlets were quick to interpret this as a subtle jab at the designer, who notoriously hated pink.

“Think pink,” he is quoted as saying, “but never wear it.”

Lagerfeld was famous for his scathing remarks against overweight people, “ugly people,” the #MeToo movement and Syrian immigrants. He appropriated Native American imagery and stereotypes in a 2013 fashion show.

Whether Chasinghorse wore pink to mock the designer is unclear, especially considering remarks she made ahead of the event.

"I feel that Karl Lagerfeld was really good at bringing people in and showing the beauty within them," she told Bazaar magazine. "I think it is beautiful to see that throughout his legacy, he has been able to uplift people and where they come from."

Native American photographer tells Indigenous tribes' stories

Ten years ago, Native American photographer and documentarian Matika Wilbur, a member of the Swinomish and Tulalip tribes in the State of Washington, set off to photograph what were at the time 562 federally recognized Indigenous tribes in the U.S. VOA reporter Natasha Mozgovaya caught up with Wilbur in Seattle to discuss her new book, "Project 562: Changing the Way We See Native America."

Berkeley Professor Apologizes for False Indigenous Identity

An anthropology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, whose identity as Native American had been questioned for years apologized this week for falsely identifying as Indigenous, saying she is "a white person" who lived an identity based on family lore.

Elizabeth Hoover, associate professor of environmental science, policy and management, said in an apology posted Monday on her website that she claimed an identity as a woman of Mohawk and Mi'kmaq descent but never confirmed that identity with those communities or researched her ancestry until recently.

"I caused harm," Hoover wrote. "I hurt Native people who have been my friends, colleagues, students, and family, both directly through fractured trust and through activating historical harms. This hurt has also interrupted student and faculty life and careers. I acknowledge that I could have prevented all of this hurt by investigating and confirming my family stories sooner. For this, I am deeply sorry."

Hoover's alleged Indigenous roots came into question in 2021 after her name appeared on an "Alleged Pretendian List." The list compiled by Jacqueline Keeler, a Native American writer and activist, includes more than 200 names of people Keeler says are falsely claiming Native heritage.

Hoover first addressed doubts about her ethnic identity last year when she said in an October post on her website that she had conducted genealogical research and found "no records of tribal citizenship for any of my family members in the tribal databases that were accessed."

Her statement caused an uproar, and some of her former students authored a letter in November demanding her resignation. The letter was signed by hundreds of students and scholars from UC Berkeley and other universities along with members of Native American communities. It also called for her to apologize, stop identifying as Indigenous and acknowledge she had caused harm, among other demands.

"As scholars embedded in the kinship networks of our communities, we find Hoover's repeated attempts to differentiate herself from settlers with similar stories and her claims of having lived experience as an Indigenous person by dancing at powwows absolutely appalling," the letter reads.

Janet Gilmore, a UC Berkeley spokesperson, said in a statement she couldn't comment on whether Hoover faces disciplinary action, saying discussing it would violate "personnel matters and/or violate privacy rights, both of which are protected by law."

"However, we are aware of and support ongoing efforts to achieve restorative justice in a way that acknowledges and addresses the extent to which this matter has caused harm and upset among members of our community," Gilmore added.

Hoover is the latest person to apologize for falsely claiming a racial or ethnic identity.

U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren angered many Native Americans during her presidential campaign in 2018 when she used the results of a DNA test to try and rebut the ridicule of then-President Donald Trump, who had derisively referred to her as "fake Pocahontas."

Despite the DNA results, which showed some evidence of a Native American in Warren's lineage, probably six to 10 generations ago, Warren is not a member of any tribe, and DNA tests are not typically used as evidence to determine tribal citizenship.

Warren later offered a public apology at a forum on Native American issues, saying she was "sorry for the harm I have caused."

In 2015, Rachel Dolezal was fired as head of the Spokane, Washington, chapter of the NAACP and was kicked off a police ombudsman commission after her parents told local media their daughter was born white but was presenting herself as Black. She also lost her job teaching African studies at Eastern Washington University in nearby Cheney.

Hoover said her identity was challenged after she began her first assistant professor job. She began teaching at UC Berkeley in the fall of 2020.

"At the time, I interpreted inquiries into the validity of my Native identity as petty jealousy or people just looking to interfere in my life," she wrote.

Hoover said that she grew up in rural upstate New York thinking she was someone of mixed Mohawk, Mi'kmaq, French, English, Irish and German descent, and attending food summits and powwows. Her mother shared stories about her grandmother being a Mohawk woman who married an abusive French-Canadian man and who died by suicide, leaving her children behind to be raised by someone else.

She said she would no longer identify as Indigenous but would continue to help with food sovereignty and environmental justice movements in Native communities that ask her for her support.

In her apology issued Monday, Hoover acknowledged she benefited from programs and funding that were geared toward Native scholars and said she is committed to engaging in the restorative justice process taking place on campus, "as well as supporting restorative justice processes in other circles I have been involved with, where my participation is invited."

Native American Photographer Tells Indigenous Tribes’ Stories

Ten years ago, Native American photographer Matika Wilbur embarked on a road trip with an ambitious goal to document all 562 federally recognized Indigenous tribes. Her multiyear work culminated in a new book aiming to change the way people see Native Americans. She launched her book tour in her home state of Washington. VOA’s Natasha Mozgovaya has more from Seattle.