Native Americans

Native American News Roundup Oct. 8-14, 2023

GAO: Federal agencies not living up to NAGPRA requirements

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) became law more than three decades ago, banning the removal of Native American cultural items from federal and tribal lands and calling on all federal and federally funded institutions to repatriate Native American human remains and funerary items.

A new Government Accountability Office report shows that 617 institutions across the United States continue to hold the remains of 104,539 Native Americans and nearly 2,620,000 funerary objects and have failed to meet their obligations under NAGPRA.

Read more:

California to crack down on NAGPRA noncompliance

In a related story, California Governor Gavin Newsom this week signed two bills to ensure the state’s public universities make NAGPRA a priority.

The California state auditor estimates that the California University system’s 21 campuses hold more than 698,000 items. Half of those campuses have not yet inventoried their holdings. More than half have not repatriated any items to tribes. Two campuses which have repatriated items failed to follow NAGPRA guidelines. Most cite a lack of funding and oversight.

Assembly bill (AB) 226 “strongly” urges the University of California to fund repatriation efforts in all its campuses and report on their progress. It also “strongly” urges a ban on using Native American remains and cultural items in teaching or research.

AB 389 requires the university to adopt and implement a systemwide NAGPRA policy and to create a NAGPRA oversight committee made up of “at least a majority” of tribe members.

Assemblymember James C. Ramos authored both bills. He is a lifelong resident of the San Manuel Indian Reservation and a member of the Serrano-Cahuilla tribe. In 2018, Ramos became the first California Native American to serve in the state assembly.

Feds agree to rebuild destroyed site in Oregon

In 2008, while adding a turn lane to an Oregon highway, the federal government bulldozed a site sacred to local Native American tribes, against the tribes’ objections.

The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation and the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde then sued the government, alleging that the destruction of their sacred site violated federal laws protecting religious freedom.

The case wound its way through federal courts to the U.S. Supreme Court. On October 5, federal authorities reached a landmark settlement agreement to replant and maintain trees it destroyed, help tribes rebuild a ceremonial stone altar and guarantee access to the site.

In the video (above), produced in 2015 by the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty which represented the tribes, tribe members explain the site's spiritual significance.

Read more:

Maine tribes: Undo edits of original constitution

On Indigenous Peoples Day, a coalition of Wabanaki tribes in the state of Maine rallied at the statehouse, calling on Maine voters to say “yes” to a proposal to restore language that has been missing from printed versions of the state’s constitution since 1876.

“It’s just about transparency, truth and restoration of our history,” Maulian Bryant, Penobscot Nation ambassador and president of the Wabanaki Alliance, told participants.

Maine was originally part of the then-Commonwealth of Massachusetts and did not achieve statehood until 1820. Article X section 7 of the original Maine constitution required Maine to “assume and perform all the duties and obligations of this Commonwealth towards the Indians.”

In other words, Maine would honor any treaties and agreements Wabanaki tribes had previously negotiated with Massachusetts.

But in 1875, possibly to hide its obligations to tribes, Maine lawmakers amended the constitution, striking that language from all printed copies. It should be noted, however, that the obligations remain in full force.

On November 7, voters will be asked whether they support restoring that section to print.

Read more:

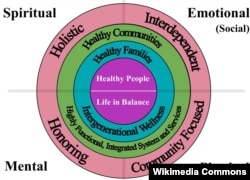

Researchers: Mental health profession must rethink treatment of Native Americans

A new report from the American Psychological Association calls on the mental health profession to develop treatment approaches based on Native American and Native Alaskan values and worldviews.

It quotes Harvard University’s Joseph Gone, an expert in global health and social medicine, who says it’s time for researchers and mental health practitioners to drop mainstream approaches and embrace “cultural humility” to avoid misdiagnosing Native Americans.

“Our way of life was considered hopelessly backwards and savage, and we were expected to become farmers and ranchers and learn reading, writing, and arithmetic,” Gone said. “The deep damage from the loss of identity contributed to postcolonial disorders such as suicide, trauma, and addiction.”

Read more:

Indigenous communities work to revitalize languages

This week, the International Conference on Indigenous Language Documentation, Education, and Revitalization (ICILDER) convened in Bloomington, Indiana, to share experiences and best practices for revitalizing Indigenous languages.

Today, only about 20% of languages once spoken across the Americans remain. VOA’s Steve Herman reported this week on efforts by one group in South Dakota to ensure the Lakota language will survive for future generations.

Read more:

US National Park to Reduce Bison Herd, Sending Animals to Native American Tribes

U.S. national park officials are planning to gather and reduce the bison herd in Theodore Roosevelt National Park in the northern state of North Dakota, rehoming the animals to a number of Native American tribes.

The "bison capture" is scheduled to start on Saturday and continue through the week in the park's South Unit near Medora. The operation will be closed to the public for safety reasons.

The park plans to reduce its roughly 700 bison to 400. The park will remove bison of differing ages.

Bison removed from the park will be rehomed and come under tribal management, InterTribal Buffalo Council Executive Director Troy Heinert told The Associated Press.

The bison will provide genetic diversity and increase numbers of existing tribal herds, he said. The Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe will receive bison; more bison could go to other tribes, depending on demographics, said Heinert, who is Sicangu Lakota.

A helicopter will herd bison into a holding area, following a survey of the landscape and a population count of the animals.

The park alternates captures every year between its North Unit and South Unit to maintain the numbers of the herd due to limited space and grazing and for herd health reasons, Deputy Superintendent Maureen McGee-Ballinger told the AP.

US Tribe Protests Decision Not To Prosecute Border Agents for Fatal Shooting

The Tohono O'odham Nation in the southern U.S. state of Arizona on Friday blasted the decision by the U.S. Attorney's Office not to prosecute Border Patrol agents who shot and killed a member of the tribe after they were summoned by tribal police.

Body camera footage released in June by U.S. Customs and Border Protection shows that the agents who fatally shot Raymond Mattia were concerned the 58-year-old may have been carrying a handgun. But no firearm was found.

The tribe's executive office called the decision not to file charges “a travesty of justice.”

“There are countless questions left unanswered by this decision. As a result, we cannot and will not accept the U.S. Attorney’s decision,” said a statement signed by Tohono O’odham Nation Chairman Verlon M. Jose and Vice Chairwoman Carla L. Johnson.

The statement said the tribe may request Congressional inquiries into Mattia's death. Mattia was killed the night of May 18 outside a home in the reservation’s Menagers Dam community near the U.S.-Mexico border.

The U.S. Attorney's Office said in a statement this week that its employees met with Mattia's family and their attorneys in Sells on September 19 to explain the decision.

“The agents' use of force under the facts and circumstances presented in this case does not rise to the level of a federal criminal civil rights violation or a criminal violation assimilated under Arizona law,” the office concluded.

“We stand by our conclusion, and we hear the Chairman’s frustration,” the statement added.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection did not immediately respond Friday to emails requesting comment.

The shooting occurred after Border Patrol agents were called to the area by the Tohono O’odham Nation Police Department for help responding to a report of shots fired.

Body camera footage shows Mattia throwing a sheathed machete at the foot of a tribal officer and then holding out his arm. After Mattia was shot and on the ground, an agent declares: “He’s still got a gun in his hand.”

CBP said earlier that the three Border Patrol agents who opened fire and at least seven others at the scene were wearing body cameras and activated them during the shooting.

The Pima County Medical Examiner's Office reported that Mattia had nine gunshot wounds.

California Governor Signs Laws Compelling Universities to Report Return of Native American Remains

Governor Gavin Newsom signed two laws Tuesday intended to compel California's public university systems to make progress in their review and return of Native American remains and artifacts.

Decades-old state and federal legislation, known as repatriation laws, require government entities to return these items to tribes. Those artifacts could include prayer sticks or wolves' skins that have been used for ceremonies. But the state auditor found in recent years that many campuses have not done so due to a lack of funding or of clear protocols from chancellors' offices.

Democratic Assembly member James C. Ramos, the first Native American in the California Legislature, said campuses' failure to return remains to tribes has denied "the Indian people the right to bring closure to family issues and historical trauma."

"We're still dealing with a state that has not come to terms with its history — deplorable history and treatment towards California's first people," Ramos said.

The laws require the California State University system and urge the University of California system to annually report their progress to review and return Native American remains and artifacts to tribes.

In 2019, Newsom issued a state apology for California's mistreatment of and violence against Native Americans throughout history. The repatriation proposals were among the hundreds of bills lawmakers sent to the Democratic governor's desk this year.

A report published by the state auditor in 2020 found that the University of California system did not have adequate policies for returning these remains and artifacts. The Los Angeles campus, for example, returned nearly all of these items while the Berkeley campus returned only about 20% of them. The auditor's office has since found that the system has made some progress.

For years, the University of California, Berkeley, failed to return remains to the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. It was not until 2018 that the university returned 1,400 remains to the tribe, according to the state's Native American Heritage Commission.

Kenneth Kahn, the tribe's chairman, said it is "appalling" that campuses have held onto Native American remains for so long and disappointing that "it's taking law" to get many universities to work to return these items.

"There certainly has been progress, but they've been under duress," Kahn said. "We've been asking for years."

More than half of the 21 California State University campuses with collections of Native American remains or cultural artifacts on campus have not returned any of the items to tribes, the state auditor's office said in a report released in June.

Some campuses have these items because they've been used in the past for archeological research, but these laws nudge the University of California and require California State University to ban them from being used for that purpose.

The University of California did not take a position on the legislation focused on its system but is committed to "appropriately and respectfully" returning Native American remains and artifacts to tribes, Ryan King, a spokesperson for the president's office, said in an email. The university system already bans these materials from being used for research "unless specifically approved" by tribes, he said. University of California released a systemwide policy in 2021 for complying with repatriation laws.

California State University supported the law setting requirements for its system and is working to teach employees about requirements to inventory and handle remains and artifacts, said Amy Bentley-Smith, a spokesperson for the chancellor's office.

- By Steve Herman

Native American Languages Fight for Survival

Monday in the United States is celebrated as both Columbus Day and as Indigenous Peoples' Day.

When the Spanish-financed Italian explorer Christopher Columbus made contact with native inhabitants of the Caribbean in 1492, there were more than 500 languages spoken across the Americas. In the land that became the United States, the remaining number of such languages has dwindled to about 100. Most now have only a handful of speakers.

Alex Fire Thunder’s two young boys are a thriving exception as their ethnic Lakota language again has thousands of aspiring speakers.

“I want them to have a strong sense of their Lakota identity. Language is everything. It’s something that nobody can take away from them,” says Fire Thunder, Oglala Lakota from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota and deputy director of the Lakȟól'iyapi kiŋ nawéčižiŋ (Lakota Language Consortium).

Fire Thunder is optimistic his sons, Odowan, 3, and Iyoyanpa, 2, will have others besides themselves to converse in Lakota when they grow up.

“There are immersion schools. There are other second-language learners learning the language and teaching their children,” Fire Thunder, who has been among those formally teaching Lakota in schools, tells VOA.

That was not the case for decades.

“My mom is a speaker, but she did not transmit the language to my siblings and I,” he says.

For generations, Native American children in North America were sent to boarding schools where they were immersed in American culture and punished for speaking their own languages.

Teaching and learning these Indigenous languages in the 21st century are a challenge because there are scant resources and opportunities remaining.

“If you want to learn Spanish, there are a number of countries you can go to where all you’re going to hear is Spanish and you’re going to be expected to speak Spanish, as well,” Fire Thunder says.

For Lakota learners there are limited options. Some elders converse in Lakota at the post office or senior centers.

“The elders that do speak are, at this point and time, all bilingual so there is no situation where you absolutely have to use Lakota,” Fire Thunder explains. “That’s something you’re not going to find if you go to Spain or Mexico.”

Lakota is part of the Sioux language group and primarily heard in the Dakotas. A unique aspect of the language is the use of kinship terms, considered an essential to Lakota cultural expression, and many of the terms do not have precise English equivalents.

“There are only about 10 to 15 languages left in the U.S. that have any viable chances in terms of moving forward beyond the next 50 years,” according to Wilhelm Meya, chairman of The Language Conservancy.

When languages lose their last fluent speakers, it can also mean the demise of their Indigenous songs and prayers.

“The average speaker is about 75. Children for the most part are not learning the language,” Meya tells VOA. “So, there’s a lot to do in order to try to get these languages back on their feet.”

Meya’s organization is a nonprofit dedicated to preserving, protecting and promoting endangered languages. It currently partners with 52 Indigenous communities. One successful project has been the creation of the New Lakota Dictionary, considered the most expansive Native American dictionary.

Hundreds of Indigenous linguists, educators and scholars are to gather this week in Bloomington, Indiana, to share knowledge and inspire language revitalization efforts.

“For the elders and the speakers, they want to pass on the language, and they want to do so with hope they’re going to leave a legacy for generations going forward,” Meya says.

Native American News Roundup Oct. 1-7, 2023

Fentanyl is hitting tribes hard; lawmaker urges Senate investigation

U.S. Senator Maria Cantwell, a Democrat from Washington, this week called on the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs to investigate the disproportionate impact of the synthetic opioid fentanyl on Native American tribes.

“American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians are on the front lines of a deadly fentanyl epidemic and are suffering,” Cantwell said in an October 2 letter to Committee chairman Brian Schatz and vice chair Lisa Murkowski. “I believe we have a duty to Indian Country to examine this crisis and work with Tribes to save lives in their communities.”

Last month, Lummi Nation tribal chairman Anthony Hillaire declared a state of emergency after five tribe members died of fentanyl overdoses in one week. Among the steps the tribe is taking is evicting the residents of a house connected with the drug.

Elsewhere, tribal drug enforcement officers on the Tulalip reservation last week seized more than 50 so-called “rainbow” fentanyl pills.

“We have not seen them before,” Tulalip police chief Chris Sutter told VOA.

He counts close to 50 fentanyl-related deaths since joining the Tulalip police force in 2018.

Read more:

OAS reviewing Native American land case against US Government

The InterAmerican Commission on Human Rights, an arm of the Organization of American States, is for the first time reviewing a land rights case submitted by a Native American nation against the United States.

In 1788, the Onondaga Nation, one of the five original nations of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy, signed a treaty with New York state, believing that the agreement provided for the shared use -- not surrender -- of nearly 2,800 hectares of land.

Since then, the Onondaga have fought for the state and federal government to acknowledge that their land was illegally taken, and they say they’re not looking for a return of the land or any reparations.

The InterAmerican Commission on Human Rights in May agreed to review their case. According to the commission website, reviews typically take less than a year.

Read more:

Virginia, Oregon tribes seek a congressional path to federal recognition

Lawmakers from Virginia and Oregon have introduced legislation seeking federal recognition for tribes in their states:

U.S. Representative Abigail Spanberger, a Democrat from Virginia, and bipartisan co-sponsors introduced a bill in support of federal recognition for the Patawomeck Indian Tribe.

Elsewhere, U.S. Representatives Hillary Scholten, a Democrat from Michigan, and John Moolenaar, a Republican from Michigan, introduced a bill calling for recognition of the Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians.

The U.S. government recognizes 574 tribes, mostly through historic treaties, making them eligible for benefits and protections.

As VOA has previously reported, non-treaty tribes who want recognition must petition the U.S. Interior Department (DOI) and meet seven strict criteria. They also have the option to bypass DOI and directly petition Congress.

Virginia tribes like the Patawomeck have a hard time meeting some of these criteria owing to records destroyed in the Civil War and a 1924 state law that classified individuals as either Black or white.

The Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians petitioned DOI for recognition in 2013 but were rejected on the grounds that they have not existed as a continuously existing community since historical times.

Read more:

Pretendian art dealer sentenced

A federal judge in Washington state has sentenced a Seattle artist to 24 months’ probation and 200 hours of community service for violating the Indian Arts and Crafts Act.

The case stems from an anonymous complaint in 2018 that Lewis Anthony Rath was selling carvings and jewelry, falsely claiming to be a member of the San Carlos Apache Tribe in Arizona.

“Counterfeit Indian art, like Lewis Anthony Rath’s carvings and jewelry that he misrepresented and sold as San Carlos Apache-made, tears at the very fabric of Indian culture, livelihoods and communities,” said Meridith Stanton, director of the DOI Indian Arts and Crafts Board, “…Mr. Rath’s actions demean and rob authentic Indian artists who rely on the creation and sale of their artwork to put food on the table, make ends meet, and pass along these important cultural traditions and skills from one generation to the next.”

Read more:

Scholar: Indigenous Peoples Day an occasion to reflect

In the United States, October 9 is still the federal holiday Columbus Day, honoring the Italian explorer Christopher Colombus. But growing numbers of states and localities have chosen to observe the day as Indigenous Peoples Day or Native American Day, acknowledging the peoples who inhabited the continent many millennia before Columbus’ “discovery.”

University of Massachusetts Lowell history chair Chrisoph Strobel, an expert in colonial-Indigenous relations, this week notes that the day should serve as a reminder not only of Indigenous resilience but of the violence Indigenous peoples endured historically.

He examines the practice of scalping, which popular culture suggests was only practiced by Indigenous Americans.

“White settlers’ wide use of scalping against Indigenous peoples is far less acknowledged and understood,” he writes, noting that they were often encouraged by scalp bounties offering money for Indian scalps.

Read more:

Federal Appeals Court Considering Native Americans Challenge to Copper Mine

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals is considering an appeal from a Native American group seeking to block the development of a copper mine on Arizona land sacred to Western Apache. VOA reporter Levi Stallings filed this story from Oak Flat.

US Agrees to Help Restore Sacred Site Destroyed for Road Project

The U.S. government has agreed to help restore a sacred Native American site on the slopes of Oregon's Mount Hood that was destroyed by highway construction, court documents show, capping more than 15 years of legal battles that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In a settlement filed with the high court Thursday, the U.S. Department of Transportation and other federal agencies agreed to replant trees and aid in efforts to rebuild an altar at a site along U.S. Highway 26 that tribes said had been used for religious purposes since time immemorial.

Members of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation and the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde said a 2008 project to add a turn lane on the highway destroyed an area known as the Place of Big Big Trees, which was home to a burial ground, a historic campground, medicinal plants, old-growth Douglas firs and a stone altar.

Carol Logan, an elder and member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde who was a plaintiff in the case, said she hopes the settlement would prevent the destruction of similar sites in the future.

"Our sacred places may not look like the buildings where most Americans worship, but they deserve the same protection, dignity, and respect," Logan said in a statement shared by the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, which represented the plaintiffs in their lawsuit.

The defendants included the Department of Transportation and its Federal Highway Administration division; the Department of the Interior and its Bureau of Land Management; and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

The Federal Highway Administration and the Department of the Interior declined to comment on the settlement.

In court documents dating back to 2008 when the suit was filed, Logan and Wilbur Slockish, who is a hereditary chief of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, said they visited the site for decades to pray, gather sacred plants and pay respects to their ancestors until it was demolished.

They accused the agencies involved of violating, among other things, their religious freedom and the National Historic Preservation Act, which requires tribal consultation when a federal project may affect places that are on tribal lands or of cultural or historic significance to a tribe.

Under the settlement, the government agreed to plant nearly 30 trees on the parcel and maintain them through watering and other means for at least three years.

They also agreed to help restore the stone altar, install a sign explaining its importance to Native Americans and grant Logan and Slockish access to the surrounding area for cultural purposes.

Native American News Roundup September 24–30, 2023

Opinion: Federal shutdown would be 'bad for Indian Country and the whole country'

Native News Online this week outlined the ways a federal shutdown would affect the 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S.:

Federally funded tribal programs would not see any new funds until funding bills pass.

If tribes have funds left over from previous years, they could use those funds to continue program operations and pay employees until those funds run dry.

If tribes do not have any leftover funds, they will be forced to find other funding sources or shutter programs entirely.

"Past government shutdowns have taken the lives of Native citizens, harmed their well-being, and forced tribal governments, tribal organizations, and individual citizens to go into debt to cover the United States' broken promises," editor Levi Rickert writes.

Parts of the federal government would cease operations if there is a lapse in appropriations caused by the absence of funding before the start of the new fiscal year October 1.

Read more:

White House orders agencies: Restore fish to Columbia River Basin

This week, President Joe Biden ordered federal departments and agencies to do what it takes to restore healthy fish populations in the Columbia River Basin.

"It is a priority of my Administration to honor Federal trust and treaty responsibilities to Tribal Nations — including to those Tribal Nations harmed by the construction and operation of Federal dams," Biden said in a presidential memorandum released Wednesday.

To that end, Biden gave departments and agencies 120 days to review any programs affecting salmon, steelhead and other native fish populations in the basin and an additional 100 days to report to the Office of Management and Budget what changes they will make and what they will need to get the job done.

Salmon once occupied nearly 13,000 miles of Columbia River Basin streams and rivers and were a mainstay of regional tribal economies and cultures.

Read more:

Interior Department to document, make public, Native American boarding school stories

The Interior Department this week announced a new project to document and make available to the public stories of Native American children forced into the federal Indian boarding school system.

"Creating a permanent oral history collection about the federal Indian boarding school system is part of the Department's mission to honor its political, trust and legal responsibilities and commitments to Tribes," said Secretary Deb Haaland in a statement Tuesday.

"The U.S. government has never before collected the experiences of boarding school survivors, which Tribes have long advocated for to memorialize the experiences of their citizens who attended federal boarding schools. This is a significant step in our efforts to help communities heal and to tell the full story of America."

The Department has granted $3.7 million to the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) to interview former students and their descendants and will shortly announce dates, times and locations for those interviews. Interested parties can sign up on the NABS website:

Read more:

Homeless crisis prompts tribe to enact state of emergency

Inflation and the rising cost of housing in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic have exacted a heavy toll on the Mashpee Wampanoag in Massachusetts. The resulting rise in homelessness prompted tribal leadership last week to enact a state of emergency.

"We are hoping the state of emergency can help us to get more federal funds and grants to eventually structure our own tribal housing authority through the tribe's Housing Department," tribal chairman Brian Weeden said.

Last year, the tribe used nearly $2 million in American Rescue Plan Act and U.S. Housing and Urban Development funding to purchase a 19-room motel which it hopes can eventually serve as transitioning shelter for tribe members in need.

"But it's not enough," Weeden said.

The council also pledged to work with local, regional, state and federal agencies and organizations to look for other solutions to the housing crisis.

Read more:

Commanders vs. 'Redskins': Nonprofit to take football team and Native advocacy group to court

A North Dakota-based nonprofit organization has filed a defamation lawsuit against the Washington Commanders football team, its leaders and the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI).

The Native American Guardians Association (NAGA) lawsuit, filed in a U.S. district court in North Dakota, accuses the Commanders and its leaders, working in tandem with NCAI, of defaming NAGA as a "fake" group comprised of "fake Native Americans."

NAGA's website states: "Each member of our leadership team has some verified Native ancestry with the majority being enrolled tribal members."

NAGA in August sent a three-page letter to the owners and leaders of the Washington Commanders, calling on them to restore the team's former name, the "Washington Redskins" and "stop the further cancel culture" against Native Americans.

The group cites a 2016 Washington Post poll of 504 Native Americans, the majority of whom said they were not offended by the "Redskins" name.

In 2020 however, University of Michigan and University of California, Berkeley researchers polled 1,000 Native Americans on their perceptions of the "Redskins" name; 49% said they found it offensive.

The National Football League team dropped the "Redskins" name in 2020 and was known simply as the Washington Football Team before adopting the Commanders name in 2022.

Reporter's Notebook: For More Than 20 Years, Ancestor Led or Taught at Various Indian Boarding and Day Schools

Editor’s Note: This is the last story in a three-part series that explores the history of the federal Indian school on the Western side of the Navajo Nation in Arizona -- and a man who taught there and in other Indian schools for more than two decades.

The 1901 Course of Study for the Indian Schools reflects the federal mission to turn Native Americans into farmers and housekeepers: Children were to spend half the day in classrooms, learning basic reading, writing and arithmetic, and spend the remainder of the day working in kitchens, fields, blacksmith shops or print shops.

There was little time for leisure: “One evening in the week should be a social hour, when the pupils may spend the evening in conversation, grand marches, etc., under the direction of the teachers,” the guide states.

On remaining evenings, teachers from various departments lectured students on farming, shoemaking and cooking so that “each child shall grasp a practical thought that may be applied in the work to be done.”

In the summer, schools were encouraged to send children on “outings” in non-Native homes and farms in the summer, where they would gain “practical experience” for their future occupations.

Some Tuba City boys were sent to work as seasonal labor in Colorado beet fields. Others remained behind to tend to the school farm.

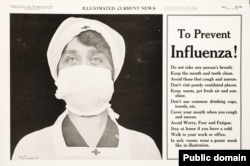

Overworked and overtired, it is little wonder they were vulnerable to infection and disease.

‘Frothing at the mouth’

Students and staff were hit hard during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. Brigham Young University anthropologist Albert B. Reagan visited Tuba City and pitched in to care for stricken students. The Kansas Academy of Science later published his harrowing account:

“Twenty-three of my boys were frothing at the mouth, and some were delirious … sanitary conditions had gotten very bad, as many of the children were wholly helpless…” he wrote. “Two of the girls died, both at night, and on account of the Navajos’ fear of death and the dead, we had to carry them out of the dormitory … with lights darkened so the other pupils would not see what we were doing.”

My great-grandfather was detailed to the Hopi day school at Moenkopi and was “overwhelmed” with caring for sick students and their families. Reagan noted that he was “heroically aided by Mr. Curn [sic] in every way possible.” They purchased sheep from a local herder and made a 75-liter (20-gallon) pot of soup which they distributed by car to the families.

“Of the 300 who were sick, only 16 died,” Reagan wrote.

In 1922, the American Red Cross (ARC) sent nurse Florence Patterson to visit several Southwestern reservations to determine whether there was a need for public health nurses.

In November 1928, Patterson told a Senate subcommittee on Indian Affairs that children at the Tuba City school were served bread, coffee and syrup for breakfast and bread and boiled potatoes at midday dinner and supper. Though the school had a dairy, only a small amount of milk was made available and was given only to “the big boys.” Children as young as 5 were given only coffee or tea.

The children were not given any of the fruit or vegetables they grew, Patterson said. These were sold to help keep the school funded.

During the same hearings, Stella Atwood, a California advocate for Native rights, testified that 11 out of 44 little boys sent to work in Colorado’s beet fields came back with typhoid; two died on the road back to school; the fate of the others isn’t known.

Over the next 20 years, Keirn bounced from the Tuba City boarding school, teaching Navajo, Hopi and Paiute children, to the nearby Hopi day school at Moenkopi. Records alternately describe him as teacher, principal or “headman.”

A family photo dated July 20, 1915, shows my great-grandfather, his wife and two older children descending the Grand Canyon by mule.

John divorced Clara in 1918, but they would be together at the newly established Theodore Roosevelt Indian School on the White Mountain Apache Reservation, where Clara contracted and died of diphtheria.

John left the Indian service in the mid-1930s and moved to California, hoping to stay with his son and daughter-in-law, who was my grandmother. Years later, she told me that the aging Keirn was demanding and ill-tempered, and they asked him to leave.

In 1941, at the age of 81, he died from complications of surgery.

Reconciling the past

I am still processing everything I have learned and hope that the ongoing Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, which launched in June 2021, will tell me more.

It is stunning to me that newspapers and genealogical and government archives were able to tell me the life story of my ancestor — a white man — but nothing about the hundreds of children he taught or the emotional, physical and spiritual hardships they may have endured.

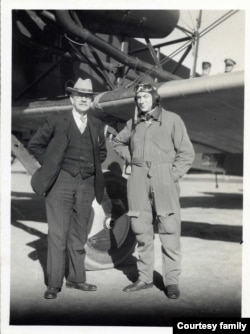

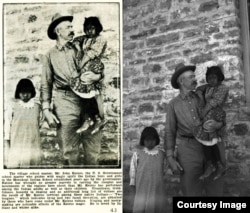

I scan his face in the photograph above but I can’t find any clues to his personality and cannot trust the glowing description of him in the clipping above as "loved by Indians and whites alike."

The little girls' expressions speak for themselves.

Most teachers didn’t last long in service, but John Keirn stayed in Arizona for more than two decades. I would like to believe that he was one of those idealistic reformers that historian Williams writes about, but instinct tells me otherwise.

Today, Americans are locked in debate over what — if any — responsibility they hold for the racist policies of the past and whether that history should be taught to future generations.

As a reporter covering Native American issues, I have had several conversations with boarding school survivors and heard heartbreaking stories about the physical, sexual and psychological abuses they endured. Discovering that a family member was complicit in a scheme to undermine Native cultures has further strengthened my resolve to learn more about how historic policies impact tribe members and their communities today.

Today, the Tuba City Boarding School is a modern facility operating under the U.S. Bureau of Indian Education. Its stated mission is to educate Navajo and Hopi children from kindergarten through eighth grade “in a safe and culturally competent environment.”

“We are running a lot of good programs here, and parents are excited about what's going on,” principal Don Coffland told me by phone. “So, we're really proud of what we do here.”

To learn more about the school, watch this student-produced video.

Native American News Roundup September 17 to 23, 2023

Here are some of the Native American-related stories making headlines this week:

Lawmakers seek to combat child abuse, neglect and family violence

The U.S. House of Representatives this week passed the Native American Child Protection Act to help Native American communities respond to and head off family violence and child abuse.

Introduced by Representative Ruben Gallego, the Native American Child Protection Act revises programs that were originally established in 1990 and passed as part of then-Senator John McCain's Indian Child Protection and Family Violence Prevention Act.

Its provisions are aimed at helping tribes develop programs to identify, investigate and prosecute cases of child abuse, child neglect and family violence.

“For too long, Congress has failed to uphold its promise to address the disproportionate levels of child abuse in tribal communities,” said Gallego, former chairman of the House Subcommittee on Indigenous Peoples of the U.S. “My bipartisan Native American Child Protection Act corrects that by providing tribes the resources they need to prevent, prosecute, and treat instances of family violence and child abuse.”

The bill now passes to the Senate for consideration.

BIA’s Missing and Murdered Unit steps in where law enforcement has failed

Agents from the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Missing and Murdered Unit are reexamining the case of Kaysera Stops Pretty Places, who went missing on August 24, 2019, in a suburban neighborhood of Hardin, Montana, less than 0.8 kilometers from the Crow Reservation boundary.

Law enforcement found her body five days after she disappeared but did not notify her family until September 11. Since then, the family says it has not heard from the Big Horn County Sheriff’s office, the FBI or the Montana Justice Department about investigations into her death.

The BIA unit was formed in 2021 by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and has received 845 case referrals, primarily from victims’ families. Nearly 375 cases are still under review or being investigated.

Read more:

White House to boost restoration of Columbia River Basin salmon

The Biden-Harris administration this week announced a historic agreement with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, and the Spokane Tribe of Indians to reintroduce salmon into blocked habitats of the Upper Columbia River Basin.

Salmon were once abundant in the upper Columbia, Sanpoil, and Spokane rivers but disappeared after their habitats were blocked by the construction of hydroelectric dams in the 20th century.

As a result, tribal communities have had to change their traditional diets and traditional ways of life, and this in turn has changed the way they once taught and raised children in the cultural and spiritual beliefs centered around these fish.

“Since time immemorial, tribes along the Columbia River System have relied on Pacific salmon, steelhead, and other native fish species for sustenance and their cultural and spiritual ways of life. Today’s historic agreement is integral to helping restore healthy and abundant fish populations to these communities,” said Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said.

The agreement includes funding to support implementing these plans, including $200 million over 20 years from the U.S. Energy Department and $8 million over two years through the Bureau of Reclamation.

Read more:

Southern Baptists expel church after pastor defended racist role play

The Southern Baptist Convention, America’s largest Protestant organization, this week voted to oust an Oklahoma pastor in Ochelata who failed to respond to allegations that his church “affirms, approves, or endorses discriminatory behavior on the basis of ethnicity.”

While the convention didn’t offer further details, it is believed to be related to two Matoaka Baptist Church events in which pastor Sherman Jaquess dressed in blackface and as a “Native American.”

The Convention’s Executive Committee voted Tuesday that the Matoaka Baptist Church was “deemed not in friendly cooperation with the convention” — the official terminology for an expulsion.

In a video released on Facebook earlier this year, Jaquess can be seen at a 2017 Valentine’s Day event dressed in blackface at a piano, posing as singer Ray Charles.

A separate Facebook photo shows Jaquess at a 2012 youth camp event dressed in red face, wearing "Native American" braids and a feathered headband.

Jaquess defended his actions, saying that it is "repugnant to have people think you're a racist" and claimed that he was paying tribute to the iconic soul singer.

"It wasn't derogatory, wasn't racial in any way, and we're not racist at all,” he said. “I don't have a racist bone in my body. I have a lot of racial friends."

He also stated he is of part-Cherokee heritage.

Read more:

Native American earthworks listed as World Heritage Site

The UNESCO World Heritage Committee this week added 27 new sites to the World Heritage List, among them the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks in southern Ohio. Those are eight enormous earthen enclosure complexes that American Indians — known as the Hopewell Culture — built between 1,600 and 2,000 years ago.

These served as centers for Hopewell feasts, funerals, and other social and spiritual gatherings. Archaeologists excavating the site have found pottery, copper and shell ornaments, and carved pipes made from raw materials obtained through trade with tribes in the Great Lakes, Carolinas, the Rocky Mountains and elsewhere.

Read more:

Danish trolls come to Seattle

John “Coyote” Halliday, an artist enrolled in the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe in Washington State, helped design one of six gigantic trolls that have appeared in the Puget Sound area.

Standing as tall as 6 meters, they are all made from recycled materials.

It is part of a larger body of work conceived by Danish artist/activist Thomas Dambo, to bring attention to sustainability and the environment.

VOA reporter Natasha Mozgovaya spoke with Halliday and Dambo in Seattle and filed this report.

UPDATE: Seattle's KOMO News reports that vandals defaced the troll sculpture featured in Natasha Mozgovaya's video report. Read more:

Reporter's Notebook: Ancestor Appointed to Teach at Western Navajo Agency in Arizona

Editor’s Note: This story is the second in a three-part series that explores the history of the federal Indian school on the Western side of the Navajo Nation in Arizona -- and a man who taught there and in a nearby day school for more than two decades.

John A. Keirn was appointed a teacher at the Western Navajo Agency in Arizona, effective November 1912, earning $84 a month on a probationary basis, according to the Haskell Indian boarding school newspaper, The Indian Leader, which tracked appointments, transfers and retirements in the Indian Service.

When Keirn arrived in Arizona, it had been 50 years since the U.S. Army began rounding up and force-marching groups of Navajo along the “Long Walk” to an internment camp at Bosque Redondo, along the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico.

The plan had been to turn the Navajo into farmers, but the experiment failed: crops failed repeatedly, conditions were bleak and the government, which was spending $1.5 million a year to feed the prisoners, finally relented and freed them.

In 1868, U.S. officials negotiated a treaty that established the Navajo reservation, which completely encircled the homelands of the Hopi. In 1882, Washington established the Hopi (then known as Moqui) reservation, which included a summer farming community at Moenkopi, 3 kilometers outside of Tuba City, which was part of the Navajo Nation.

Army campaigns against Native tribes in the Southwest ended with the capture of the Apache leader Geronimo in 1886; now, the U.S. turned its attention from warfare to forced assimilation.

U.S. Army General Richard H. Pratt in 1878 had established the first of many federal off-reservation Indian boarding schools in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. By 1908, the government was operating 88 reservation boarding schools, 26 non-reservation schools and 165 day schools.

These included the Keams Canyon Boarding School for the Hopi (then called Moqui), which, like many boarding schools would come to be known by several names, and the Western Navajo Agency Boarding School, established at an abandoned trading post at Algert, in Arizona’s Blue Canyon.

When the government failed to make needed improvements to the Blue Canyon site, school staff, students and local Navajo stonemasons hauled stone and constructed their own school buildings.

“Oil-can cases were used for window frames and goods boxes were utilized for lumber to make doors, etc.,” the agency superintendent wrote in his 1901 report to the Commissioner for Indian Affairs in Washington.

In 1903, the government moved its Western Navajo Agency headquarters to Tuba City, an oasis fed by a tributary of the Little Colorado River. The city’s name belied its size; at the time, it consisted only of a trading post and a handful of buildings left by earlier Mormon settlers.

In 1904, the government began constructing a new boarding school to replace the Blue Canyon school: The new Tuba City Boarding School was comprised of three imposing buildings, arranged symmetrically in an architectural style typical of federal buildings at the time.

“Such an arrangement suggests both system and the authoritative, almost military-like, approach to education that dominated BIA thinking through the first two decades of this century,” reads a National Park Service survey of the buildings.

The children slept in “large impersonal sleeping rooms” that doubled as classrooms. As the student population grew, the agency added 40-bed sleeping porches to the boys’ and girls’ dormitories.

Gradually, the school expanded to include a classroom building, mess hall, steam laundry and employee living quarters. By the late 1920s, the campus included a 50-bed hospital, barn, garages and machine shop.

Bugles and drills

In her 1954 memoir “The Red Moon Called Me,” Gertrude Golden, a teacher in the Indian Service from 1901 to 1918, described student life in non-reservation boarding schools as highly regimented.

“The pupils were divided into companies according to age and size, and each company had its captain, lieutenants and corporals,” she wrote. “These officers drilled their companies in marching, setting-up exercises and simple military maneuvers.”

In his 1914 annual report to the Interior Secretary for 1913, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Cato Sells said that as a means to ensure uniform systems of drilling in these schools, “a pamphlet has been published for the use of employees reproducing a portion of the Manual for Infantry Drills now used by the United States Army.”

A former student at the Tuba City school would later recall: “In the morning, the bugle would blow, and all the children would go out and line up to salute the flag while the bugler played, and then they marched to the dining hall.”

Tuba City students earned their keep working on the school’s 200-acre farm, which included garden plots, a large apple and pear orchard, and about 40 hectares each of alfalfa and corn.

Students raised and butchered their own livestock, canned fruits and vegetables for the winter, and in cold months, harvested ice for summer.

Sometime before 1920, my great-grandfather took a series of photographs (see photo gallery, below). These ended up in Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, which digitized them for VOA. Because the children are young, I assume that they were Hopi children attending the Moenkopi Day School.

Never made public before, the photos (above) are gut-wrenching: children, some of them not much older than 4 or 5, stand in the hot sun behind mounds of picked apples; boys lean on hoes amid rows of what appears to be lettuce.

One photograph shows the children holding Navajo rugs and popular monthly magazines like McClure’s, which would have been completely foreign to them, both in language and cultural content.

Not one child is smiling.

NOTE: Part Three of the series examines student health and nutrition.

Reporter's Notebook: Finding That My Ancestor Taught in an Indian Boarding School

Editor’s Note: This story is the first in a three-part series that explores the history of the federal Indian school on the Western side of the Navajo Nation in Arizona — and a man who taught there and in a nearby day school for more than two decades.

One Sunday last May, I logged into a popular genealogical site to research my family tree. Specifically, I wanted to know more about my mother’s grandfather, John A. Keirn, who had left his wife and three children and moved out West.

Searching his name in newspaper archives, I was shocked to find a small notice in the August 5, 1927, issue of Arizona’s Coconino Times newspaper: Keirn had been the principal of the Western Navajo Indian boarding school in Tuba City, Arizona.

Keirn was my ancestor by marriage, not by blood; but that did not make him any less family. His son, my step-grandfather, had been an important influence growing up. I felt embarrassed, almost betrayed, having researched and written about some of the horrors perpetrated at schools like this one.

And then I remembered hearing he had a bad temper. That bothered me more than anything else. I wondered how many children had felt its sting.

I had to know more.

Digging through archives

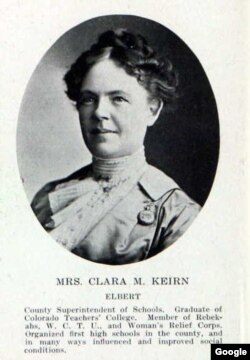

Census records show Keirn, the son of a farmer, moved from Illinois to Omaha, Nebraska, in the early 1890s to teach school. There, he met his future wife, fellow teacher Clara Rood. They married in 1896 and eight years later moved to rural Elbert County, Colorado, where Clara got a job teaching.

At the time, schools in rural counties were makeshift and scattered: Clara rode on horseback from one school to another. In 1907, she was elected president of her school district and in 1908, promoted to county superintendent of schools.

But her husband was not so lucky. He drifted from one job to another — working at the local mercantile store or on a railroad bridge gang.

In November 1912, Clara was up for reelection and nearly lost over public charges of nepotism: She had opened the county’s first high school and appointed her husband as its sole teacher. He was earning $100 a month — a generous salary — to teach only two students.

Voters also questioned why the couple’s oldest daughter had been sent away to school in Omaha instead of attending one of the schools that Clara supervised.

Ten days after the allegations surfaced, the Elbert County Tribune reported that John Keirn had left Colorado for Arizona.

Vocation, escape or last resort?

It is hard to imagine what motivated my great-grandfather to leave a wife and three children — the youngest, my step-grandfather, only a boy of 7 — to join the Indian service.

Denver was only 80 kilometers (50 miles) away and by 1912 had a well-established school system.

It is possible that Keirn could not meet Denver’s hiring requirements: A 1928 report of conditions on Indian reservations — a so-called Meriam Report — noted that the government regularly hired teachers whose credentials would not be accepted by any good public school system.

“… there is even some evidence that the Indian Service is receiving teachers who have been forced out of the schools of their own states because they could not meet the raised standards of those state,” investigators said.

Historian David Wallace Adams, author of “Education for Extinction,” writes that some teachers were driven by “a sense of Christian responsibility to save a vanishing race from extinction.”

In her 1954 memoir “Red Moon Called Me,” Gertrude Golden, a former teacher in the Indian Service, noted that when Native American children were fortunate enough to have good teachers, “inestimable good was accomplished.”

“But it happened all too frequently that the teacher was in the work only for money and adventure and acted upon the principle that ‘anything is good enough for a lousy Indian,’” she wrote.

Another possibility is that Keirn was looking to leave his marriage.

Whatever his motive, he would have seen one of the job notices that the U.S. Civil Service Commission periodically published in regional newspapers.

He would have had to pass a civil service examination requiring him to write neatly, spell correctly, draw a simple picture and write brief essays on questions in basic algebra, geography, history, physiology and hygiene, nature study and American literature. The U.S. Civil Service Commission (CSC) published sample questions such as:

“Compare Ohio and Cuba as to climate, physical features, vegetation, leading industries, character of inhabitants, form of government, etc.”

“Discuss the peculiarities, characteristics, habits, etc., of the bobolink [a songbird], including food, mode of nesting and rearing young, etc.”

“A field is in the form of an isosceles triangle. The two sides are 26 rods each and the base is 20 rods. What is the altitude?”

The CSC cautioned applicants: “The object of the schools is to prepare the Indian youth for the duties, privileges and responsibilities of American citizenship by training them in the industrial arts and developing their moral and intellectual faculties ...“The conditions of life at these schools differ from ordinary school or home life … There is little opportunity for recreation or social pleasure."

NOTE: Part Two of this series will explore student life at the Tuba City Boarding School.

Native American News Roundup September 10-16, 2023

Leonard Peltier supporters arrested, fined during Washington protests

U.S. Park Police issued citations to more than two dozen supporters of imprisoned Native American activist Leonard Peltier during a rally outside the White House Tuesday.

The event was co-hosted by the South Dakota-based activist group NDN Collective and the human rights group Amnesty International.

As VOA reported in 2016, Peltier, an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa tribe of Lakota and Dakota descent, was convicted in the murders of two FBI agents during a 1975 standoff at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota and given two consecutive life sentences.

His supporters say he was framed for murders he didn’t commit. Federal agents say evidence shows he was guilty of shooting agents at close range and that he has shown no remorse.

Peltier, 79 and in ill health, has spent 46 years in prison, losing multiple appeals for parole and White House clemency.

The U.S. Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 allows “compassionate release” for prisoners over 70 who have completed at least 30 years of their sentences. But because Peltier was sentenced before the law went into effect, he is ineligible.

“We come together here to remind the United States that Leonard Peltier is the longest-incarcerated political prisoner in the history of the United States,” NDN Collective CEO Nick Tilsen (Oglala Lakota) said Tuesday. “… We cannot let his fight for freedom go quietly. It's time — 48 years is long enough.”

Park Police spokesman Sergeant Thomas Twiname said that officers issued citations to 27 demonstrators for the misdemeanor violation of “incommoding,” that is, crowding or obstructing a sidewalk.

“Nobody was put in handcuffs,” he said. “They were given citations, and then the individuals left.”

Indigenous researchers stress Indigenous sovereignty over biomedical data

The Daily Yonder this week highlights the work of the Native BioData Consortium (NativeBio), a nonprofit research collective led by Indigenous scientists and scholars seeking to use health data to improve and protect the health, welfare and cultures of Indigenous peoples.

Government agencies and scientific researchers have a history of unethical research among Native Americans. In the 1950s, for example, the U.S. Air Force gave capsules filled with radioactive Iodine-131 to Alaska Natives as part of a thyroid function study, putting them at risk of developing thyroid cancer.

In the early 1990s, an Arizona State University professor took blood samples from the Havasupai Tribe to understand the prevalence of diabetes in that community. Those samples ended up in the hands of researchers in other institutions, who used them for research on schizophrenia, inbreeding and theories about ancient migrations from Asia to North America.

NativeBio, located on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, works to break down mistrust of science.

“Our main mission is to be a safe harbor for all indigenous people, and even marginalized people around the world whose data has been collected since the ‘70s and is being collected now, and not giving them enough consideration or control of how their data is used or commercialized,” said Joseph Yracheta, executive director of NativeBio.

Read more:

Native tribes, mining groups, at odds over massive lithium find in Nevada

Scientists say that lithium discovered three years ago in a collapsed supervolcano in Nevada could meet global demand for decades.

A new analysis of the southern portion of the McDermitt caldera in Nevada called Thacker Pass shows that claystone made up of the mineral illite contains 1.3% to 2.4% of lithium in the crater, nearly double the levels in more common lithium-bearing magnesian smectite clay.

Since 2021, local tribes and environmental groups have tried without success to halt mining construction at Thacker Pass, which lies in the traditional homelands of the Paiute, Shoshone and Washoe people.

Read more:

US court sentences man for looting Native American archaeological site

A California man has been sentenced to three years of probation and ordered to pay more than $10,000 in restitution for illegally digging up and removing Native American human remains and cultural artifacts from public land in violation of federal law.

The case dates to July 2015, when wildfire fighters stumbled upon an excavated site in the Sierra National Forest.

“Human remains and artifacts were located among large piles of sifted dirt, hand tools and a large screen sifting box,” the Justice Department stated in 2018.

A video camera at the site captured Vance Franklin Myers excavating the site multiple times, sometimes in the company of a woman, a small child and a dog.

The items he looted were valued at nearly $60,000.

Archaeologists stabilized the site, human remains were reburied, and artifacts were returned to the North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians.

Read more:

Native American News Roundup September 3 – 9, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Interior Department cancels Arctic oil and gas leases

The Biden-Harris administration announced this week that it will cancel oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) purchased by state developers on the last day of the Trump administration.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said Wednesday that the “lease sale itself was seriously flawed and based on a number of fundamental legal deficiencies.”

“With today’s action, no one will have rights to drill for oil in one of the most sensitive landscapes on Earth,” Haaland told reporters. “Climate change is the crisis of our lifetime, and we cannot ignore the disproportionate impacts being felt in the Arctic.”

The administration will also ban new leasing on more than 10 million acres in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, the largest undisturbed public land in the United States.

Forty-year fight

In 1980, Congress opened 1.5 million acres inside the refuge to oil and gas development. In 2017, Congress passed a tax reform bill authorizing the Interior Department to hold two lease sales by the end of 2024.

The state’s own economic development arm -- the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA) – bought 10-year leases covering more than 174,000 hectares (430,000 acres) of land.

The land in question is estimated to hold more than 7 million barrels of oil and 198 billion cubic meters (7 billion cubic feet) of natural gas.

In June 2021, the Biden administration put a hold on all drilling, pending an environmental review. AIDEA sued Biden and several other administration officials.

“The lawsuit is in direct response to unlawful actions to obstruct and delay the development of valid oil and gas leases in the non-wilderness Coastal Plain (Section 1002 Area) of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR),” AIDEA said in a press release at the time.

Last month, a federal judge dismissed the suit.

Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy was quick to react to Haaland’s announcement this week.

“The leases AIDEA hold in ANWR were legally issued in a sale mandated by Congress. It’s clear that President [Joe] Biden needs a refresher on the Constitution’s separation of powers doctrine. Federal agencies don’t get to rewrite laws, and that is exactly what the Department of the Interior is trying to do here,” he said.

AIDAI said it will continue to “aggressively defend” its lease rights.

Read more:

Cherokee Chief condemns Oklahoma governor's pick for tribal liaison

Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt, a member of the Cherokee Nation, has added a Native American tribal liaison to his leadership team. His choice is John Wesley “Wes” Nofire, a retired boxer, former member of the Cherokee Nation tribal council and harsh critic of principal chief Chuck Hoskin Jr.

In a statement released Tuesday, Stitt’s office described Nofire as “outspoken about the challenges the Supreme Court’s McGirt decision has created when it comes to administering justice fairly for every Oklahoman, native and non-native alike.”

In McGirt v. Oklahoma, U.S. Supreme Court justices reviewed the case of a Native American accused of the rape of a 4-year-old Native child on the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. An Oklahoma court sentenced him to two 500-year sentences and life without parole.

More than 20 years later, his lawyers appealed, arguing that because Congress had never formally disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the crime took place on tribal land. They cited the Major Crimes Act, an 1885 law that says when serious crimes are committed by or against a tribal member on tribal or reservation land, only the federal government, not the state, has the right to prosecute.

The Supreme Court agreed.

Though the ruling applies only to criminal jurisdiction, many in Oklahoma worry it could expand to other areas of law enforcement and beyond into environmental and energy arenas.

Hoskin took to Facebook to condemn Nofire, whose political views are said to align with Stitt’s.

“It’s difficult to overstate the active threat that Governor Stitt’s new Native American Liaison, Wes Nofire, poses to tribal sovereignty,” he wrote. “He is on the record opposing tribal sovereignty and peddles dangerous and unhinged conspiracy theories.”

In an interview with Oklahoma’s KOKO-TV, Nofire sent a message to Hoskin and other critics:

"Give me a little bit more time and allow me to be that olive branch. It grows. That’s one thing that they do is when we reach out the hand of opportunity to reach back and let’s work on these things, and I think we have a lot of opportunity there," Nofire said.

Native American News Roundup Aug. 27-Sept. 2, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

New count of Indian Boarding Schools: 523 and likely growing

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) this week released an interactive digital map identifying 523 Indian boarding schools across the United States. That’s 115 more than were identified in the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report of May 2022 that counted Indian boarding schools operated, funded, or supported by the U.S. government.

The new map includes both federally operated boarding schools and institutions run by various religious entities. It also identifies known residential schools in Canada.

The project has been three years in the works, and the group’s Deputy CEO Samuel Torres (Mexica/Nahua) expects more schools will come to light.

“I believe this tool is going to greatly help our relatives who are seeking answers and who are on their own healing journeys,” he said in a statement. “Every Indigenous person in this country has been impacted by the deliberate attempt to destroy Native families and cultures through boarding schools. For us to visually see the scope of what was done to our communities and Nations at this scale is overwhelming, but this work is necessary to uncover the truth about this dark chapter in American history.”

Native News Online reports that NABS is hoping to launch a database in November containing nearly 50,000 records collected from boarding and residential schools.

Read more:

University professor and accused ‘pretendian’ resigns

Andrea Smith, once a well-regarded scholar of Native American studies, has agreed to resign from the University of California at Riverside after more than a decade of accusations that she falsely claimed Cherokee identity.

VOA obtained a copy of the separation agreement signed by Smith in January 2023 and by university chancellor Kim Wilcox in December 2022. It states that Smith will teach through the summer of 2024 and will then retire as a professor emeritus with the following stipulation:

“Professor Smith agrees that her status as a professor emeritus will not be listed on the university directory information websites.”

In addition, the university will pay her related legal fees up to $5,000.

As VOA has reported previously, Native American scholars say ‘race shifting’ is prevalent in universities across North America. In a 2022 interview with VOA, Kim TallBear, (Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate) a professor at the University of Alberta, explained why the practice is harmful:

"Non-Indigenous people with non-Indigenous community standpoints who pose as Indigenous and who rise through the professional ranks falsely represent our voices," TallBear said. "They theorize Indigenous peoplehood, sovereignty and anti-colonialism. They become thought leaders, institutional decision-makers and policy advisers to governmental leaders with regulatory and economic power over our peoples and lands."

Read more:

Native American Church to Washington: Protect our Peyote

The Native American Church of North America (NACNA) will next month hold a second “boots on the ground” effort in Washington, calling on federal agencies and lawmakers to help protect peyote from the effects of climate change, corporate agriculture and so-called “drug tourism.”

“We will remind federal government agencies that laws established by them in 1978 and 1994” allow Native American Church member to “exercise our rights,” church president Jon Brady posted to members on Facebook.

Peyote is a small, button-shaped cactus that contains psychoactive alkaloids and grows only in southern Texas and parts of northern Mexico. Indigenous people have used it ceremonially and medicinally for centuries.

It was banned in the United States in 1970, but the law was later amended to allow its use in “bona fide religious ceremonies of the Native American Church.”

Cherokee Nation boosts TV and film production

The Cherokee Nation has launched a new media company to consolidate its existing Cherokee Film Productions, Cherokee Film Studios, Cherokee Film Commission, and Cherokee Film Institute.

The new Cherokee Film company will continue sharing the tribe's stories through OsiyoTV and is planning new projects to tell Cherokee stories and boost the revitalization of the Cherokee language.

“Cherokee Nation has quickly become a leading hub for Indigenous storytellers in television and film,” Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. said in a statement. “As we increase infrastructure, explore incentives, connect resources and remove barriers, Cherokee Nation and its businesses are helping grow and amplify television and film production in Oklahoma while making it possible for our citizens to be a part of it.”

Read more:

You can watch Cherokee Film’s documentary series Osiyo: Voices of the People, here:

Pacific Northwest tribes welcome Polynesian navigators

Hōkūle'a, a traditional Polynesian deep-sea canoe, is on a four-year voyage around the Pacific Ocean to raise awareness about climate change.

The canoe sailed into Elliott Bay in Seattle, Washington, early Wednesday morning, escorted by traditional Suquamish canoes with Muckleshoot and Hawaiian canoes there to greet them.

VOA correspondent Natasha Mozgovaya was there and filed this report: