Native Americans

Native American News Roundup Dec. 3-9, 2023

Tribal leaders and top administration officials convene in nation’s capital

The White House hosted its third annual Tribal Nations Summit this week as part of its goals of strengthening nation-to-nation relationships and boosting tribal sovereignty.

It was a chance for the Biden administration to showcase investments in Indian Country in 2023 and to look forward — President Joe Biden’s 2024 budget request includes $32.6 billion to support the Indian Health Service, tribal public safety, housing, education and more.

During his address to tribal leaders on Wednesday, Biden noted some challenges tribes face in getting federal funds.

“Today, there are still too many hoops to jump through … too many strings attached, and too many inefficiencies in the process,” he said, announcing an executive order to reform the tribal funding process.

“It requires federal agencies to streamline grant applications, to co-manage federal programs, to eliminate heavy-handed reporting requirements,” Biden said. “It gives tribes more autonomy to make your own decisions.”

The administration has set up an Access to Capital Clearinghouse online, a “one-stop-shop” of all federal funding opportunities.

The order requires federal agencies to assess all funding gaps and shortages, come up with strategies to make up for unmet needs and report annually on their progress.

The order also secures the first-ever advance appropriations for the Indian Health Service so that it can continue providing health care services to tribes during government shutdowns or other funding lapses.

The administration also announced more than 190 co-stewardship agreements with tribes, which are meant to give them greater say in the management of federal lands, waters and resources.

These include the first-ever agreement with the Commerce Department, more than 70 agreements with the Interior Department and more than 120 co-management and co-management agreements with the Agriculture Department.

Park Service, Interior to study Impact of the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland told the summit that the National Park Service will collaborate with tribes across the U.S. to conduct a new study focused on the Indian Reorganization Period.

“Native American history is American history, and it should be told by Indigenous peoples. The stories we share inform not just our present but the future world we will pass on to the next generation of leaders. They help define us,” Haaland said. “I am grateful that the National Park Service will work closely on this study with Native communities to ensure that their stories, perspectives and Indigenous knowledge are a key part of this work.”

Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) in 1934, ostensibly to improve conditions among Native Americans. It put an end to the land allotment and forced assimilation policies of the past. It offered tribes incentives to replace traditional governments with U.S. styles of governance, supervised by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Of the 263 tribes that voted on the IRA, 71 rejected it and 192 accepted it. Rifts between “Old Dealers” and “New Dealers” continue to play out on some reservations today.

Read more:

Biden backs Haudenosaunee bid for the Olympics

During his speech to tribal leaders, President Biden backed allowing the Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s lacrosse team to compete in the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles.

The Haudenosaunee are a confederacy of six Indigenous nations — the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca and Tuscarora — who are credited with inventing the game which the Mohawk call Tewaarathon, or “little brother of war.”

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) in October voted to bring lacrosse back to the Games, and the Haudenosaunee want to compete under the flag of the confederacy.

“Their ancestors invented the game,” said Biden. “They perfected it for a millennia. Their circumstances are unique, and they should be granted an exception to field their own team at the Olympics.”

They face a hurdle, however.

“Only national Olympic committees recognized by the IOC can enter teams for the Olympic Games,” the IOC said in an emailed statement to The New York Times.

Cambridge to honor city’s original occupants

In 2024, Cambridge, Massachusetts, plans to erect 70 new street signs with Massachusett-language translations of numbered streets.

The plan was proposed by Sage Carbone, a Cambridge resident with Italian and Native ancestry.

“There are no streets named after Native people in Cambridge,” Carbone told Boston Public Radio. “To my knowledge, there are no squares commemorating Indigenous people. There are no distinctive markers of the historical nature.”

The plan was approved in December 2021 as part of the city’s $180,000 African American & Indigenous Peoples Historical Reckoning Project, which also looks to restore and expand the existing African American Heritage Trail in Cambridge.

Read more:

- By Anita Powell

Cherokee Nation Chief Speaks to VOA on US Promises, Progress

President Joe Biden convened a two-day summit Wednesday with the heads of more than 300 tribal groups, saying his administration is committed to writing “a new and better chapter of history” for the more than 570 Native American communities in the United States by making it easier for them to access federal funding.

Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. of the Cherokee Nation, one of the largest Indigenous tribes in the United States, spoke to VOA about those efforts and also some of the themes of Native history that are in the forefront today.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

VOA: What are your goals for your half-million citizens at this summit?

Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr.: It’s to press the administration on meeting America's commitment but also learn more about what their plans are. ... The most important thing for the Cherokee Nation, I think — and all tribes — is the efficient deployment of resources, and then allowing tribes to decide how to use those resources. So, a more efficient, streamlined process in terms of getting funding out.

VOA: The Biden administration says it will release at this summit a report card of sorts. What’s your assessment of how the administration has succeeded and where it could do better?

Hoskin: I think overall, it's been very, very positive. ... The bipartisan infrastructure deal has been important for the Cherokee Nation. The American Rescue Plan has enabled us to do things that may seem small to the rest of the world, like putting a cell tower in a community that didn't have cellphone access, by improving water systems.

VOA: Any criticism?

Hoskin: To the extent that it's criticism: The federal government's a big ship, it's tough to steer. What I have seen over the years is, you get a new administration in, it takes a while for the relationships to be built up, for executive orders on consultation to translate down to agencies.

VOA: President Biden has not made — publicly, at least — any sort of land acknowledgment statement. Is that something you seek?

Hoskin: Reminding the country that there were aboriginal people here before anyone ever heard of the United States, I think that's important. But I think in terms of what tribal citizens want to see, and what tribal leaders want to see is access to land, control of resources, more land placed into trust for the benefit of Native Americans.

VOA: The current war between Israel and Hamas is also about land. Do you have any advice for President Biden, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas during this very tense moment?

Hoskin: I do think there are some parallels. You're talking about people who say that they've been on the land from time immemorial. That's what we Cherokees say, and we have a history of being dispossessed from our land. I would just remind people that there's a way to balance rights. I think we're trying to do that in the United States in terms of Indian Country versus the rest of the country. We haven't perfected it, but I think we're making some progress. So, all I would say is the respect and dignity that every human being deserves ought to be on display anytime you're having these sorts of situations. That’s a difficult sentiment to express in the midst of some real difficulties.

VOA: Adversaries of the U.S. have weaponized the well-documented suffering of Native Americans, saying the U.S. doesn't have the moral high ground on the world stage.

Hoskin: Certainly it would be accurate to say the United States has an appalling record towards Indigenous peoples. Is it perfect now? No, it's not. But we're making progress. I mean, think about what's happened on the world stage. In Australia, that country just rejected the recognition of aboriginal people. In the United States, we have federal recognition. ... We do have a foundation upon which we built a great deal. And so, to those critics of the United States, I would say, come to the Cherokee Nation and look at what we're doing, leading in things like health care and lifting up people economically. It's not perhaps the picture that has been painted by some of these regimes.

VOA: I believe you knew [former Cherokee chief] Wilma Mankiller very well. Talk a bit about her.

Hoskin: Anybody in the world who cares about human rights, the dignity of everybody, civil rights, they should get to know her. ... She reminded us of who we are and what we always had in us, which was the ability to govern ourselves, to protect ourselves, to understand we have this common history and destiny. She reminded us that we were Cherokee after generations of being suppressed and a bit beaten down. So, she lifted us up. The fact that there's a Barbie doll that depicts her, that there's a quarter from the United States Mint — that shows what a powerful person she was.

VOA: How do you feel about not being consulted on the Barbie doll?

Hoskin: Well, I think it's disrespect on the part of Mattel, but I will also tell you that they very quickly understood that, and we're engaging. So, I think that overall, I appreciate Mattel depicting Wilma Mankiller, the great Cherokee chief. On balance, this is a good thing.

VOA: What does it mean to you to be an American?

Hoskin: I think a lot about this. I can go back a few generations to my ancestors who signed up to fight for this country in World War I and World War II — while within their living memory, there was a great deal of oppression and atrocities by this country to their own people. But in terms of the principles of what we want for this country, like freedom and opportunity for everyone, if we aspire to that, that's something we all share. And so for me, that's what it means to be an American.

VOA: How do you feel about public holidays like Columbus Day and Thanksgiving?

Hoskin: Columbus Day is abhorrent. [Christopher Columbus is] demonstrably somebody who engaged in great atrocities towards Native peoples. ... There's plenty to celebrate in American history without celebrating and misstating what he did. In terms of Thanksgiving, I think it's become for the Cherokee people something that we just celebrate in terms of what unites humanity, which is giving thanks for what we have and trying to do better.

VOA: Anything else you'd like to tell our audience? We broadcast in 48 languages. Would you like to say something in your language?

Hoskin: Sure. I'd say “osiyo,” which is “hello” in Cherokee. And “donadagohvi,” which is ”we will see each other again.” We don't say goodbye. We just look forward to seeing people again. I look forward to seeing you again.

VOA: And I look forward to seeing you again.

What Mattel Got Right — and Wrong — in Designing the Wilma Mankiller Barbie

Members of the Cherokee Nation were delighted last month when the Mattel toy company released a special edition Barbie honoring the tribe’s first female principal chief, women’s advocate Wilma Mankiller.

“She truly exemplifies leadership, culture and equality and we applaud Mattel for commemorating her in the ‘Barbie Inspiring Women Series,’” Cherokee principal chief Chuck Hoskin said in a statement.

Not long after the doll was shipped, Cherokee buyers began complaining that Mattel had not done its homework.

Some said the doll’s skin tone was too dark, implying an effort to make the doll look more “Indian.”

The Cherokee have always been well-known for their traditional basketry styles, but the doll's basket is patterned after traditional English baskets.

She wears a tear dress (pronounced tare), the official dress of Cherokee Nation women, but she is not wearing any jewelry.

“Chief Mankiller was well known for her tribal necklaces,” Cherokee researcher David Cornsilk told VOA via Facebook. “And in addition to being the first female chief of a major U.S. tribe and first woman chief of the Cherokee Nation, she was the first woman to wear our traditional gorget necklace, a powerful symbol of leadership.”

The gorget is a crescent-shaped metal plate that the British military gifted to 18th Century tribal chiefs as a reward for loyalty and a symbol of authority. They are still worn by Cherokee chiefs today.

Missing, too, Cornsilk and others say, are the traditional pucker-toe moccasins, always worn with official dress.

Perhaps the most glaring error is on the doll’s package, which features the Great Seal of the Cherokee Nation.

“The word ‘Cherokee’ should be ᏣᎳᎩ but is written as ᏣᏔᎩ,” Cornsilk said.

Which, translated, reads: “The Chicken Nation.”

A Google search shows the mistake may have come from an image posted on Wikipedia that was created in 2013 by a now-retired contributor. It, too, reads, “Chicken.”

A note beneath the faulty seal challenges its “factual accuracy.”

Mattel spokesperson Devin Tucker told the Associated Press that the company is aware of the problem and is “discussing options.”

Mankiller’s daughter corrects the record

Mankiller’s only surviving child, Felicia Olaya, was disappointed that she was left out of the Barbie design process, just as she says she was with a 25-cent coin the U.S. Mint released in 2022.

“Just like when the quarter came out, neither my sister, who was living at that time, nor I knew anything about it,” she told VOA. “We found out about it secondhand or on social media.”

“And then this happens. And there've been a few other small events that have happened over the years that we didn't know about until they were done,” she added.

Mattel says it worked with Mankiller's husband, Charlie Soap, and his production partner Kristina Kiehl. Neither Soap nor Kiehl responded to messages left by the AP.

Olaya is less critical of the doll itself than some others in the Cherokee Nation.

“It's a doll. It’s not supposed to be an exact portrait of my mom,” she said.

She would change the doll's eye color, something not easily detectable in photos.

“Her eyes weren’t brown. They were hazel,” she said. “And yes, my mom was a jewelry person. She wore clay or cornseed bead necklaces a lot, so, I would have added those.”

She does credit Mattel with getting it right on the shoes.

“Some people say she should have been wearing pucker moccasins. Well, my mom never wore them,” Olaya said, explaining that Mankiller suffered from chronic foot pain after a near-fatal car accident in 1979.

“She either wore flip flops or the kind of shoes the doll is wearing, like diabetics’ shoes.”

Barbie Doll Honoring Cherokee Nation Leader Met With Mixed Emotions

An iconic chief of the Cherokee Nation, Wilma Mankiller, inspired countless Native American children as a powerful but humble leader who expanded early education and rural health care.

Her reach is now broadening with a quintessential American honor: a Barbie doll in the late Mankiller's likeness as part of toymaker Mattel's "Inspiring Women" series.

A public ceremony honoring Mankiller's legacy is set for Tuesday in Tahlequah in northeast Oklahoma, where the Cherokee Nation is headquartered.

Mankiller was the nation's first female principal chief, leading the tribe for a decade until 1995. She focused on improving social conditions through consensus and on restoring pride in Native heritage. She met with three U.S. presidents and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian award.

She also met snide remarks about her surname — a military title — with humor, often delivering a straight-faced response: "Mankiller is actually a well-earned nickname." She died in 2010.

The tribe's current leader, Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr., applauded Mattel for commemorating Mankiller.

"When Native girls see it, they can achieve it, and Wilma Mankiller has shown countless young women to be fearless and speak up for Indigenous and human rights," Hoskin said in a statement. "Wilma Mankiller is a champion for the Cherokee Nation, for Indian Country, and even my own daughter."

Mankiller, whose likeness is on a U.S. quarter issued in 2021, is the second Native American woman honored with a Barbie doll. Famed aviator Bessie Coleman, who was of Black and Cherokee ancestry, was depicted earlier this year.

Other dolls in the series include Maya Angelou, Ida B. Wells, Jane Goodall and Madam C.J. Walker.

The rollout of the Mankiller Barbie doll, wearing a ribbon skirt, black shoes and carrying a woven basket, has been met with conflicting reactions.

Many say the doll is a fitting tribute for a remarkable leader who faced conflict head-on and helped the tribe triple its enrollment, double its employment and build new health centers and children's programs.

Still, some Cherokee women are critical, saying Mattel overlooked problematic details on the doll and the packaging.

"Mixed emotions shared by me and many other Cherokee women who have now purchased the product revolve around whether a Wilma Barbie captures her legacy, her physical features and the importance of centering Cherokee women in decision making," Stacy Leeds, the law school dean at Arizona State University and a former Cherokee Nation Supreme Court justice, told The Associated Press in an email.

Regina Thompson, a Cherokee basket weaver who grew up near Tahlequah, doesn't think the doll looks like Mankiller. Mattel should have considered traditional pucker toe moccasins, instead of black shoes, and included symbols on the basket that Cherokees use to tell a story, she said.

"Wilma's name is the only thing Cherokee on that box," Thompson said. "Nothing about that doll is Wilma, nothing."

The Cherokee language symbols on the packaging also are wrong, she noted. Two symbols look similar, and the one used translates to "chicken," rather than "Cherokee."

Mattel spokesperson Devin Tucker said the company is aware of the problem with the syllabary and is "discussing options." The company worked with Mankiller's estate, which is led by her husband, Charlie Soap, and her friend Kristina Kiehl, on the creation of the doll. Soap and Kiehl did not respond to messages left by the AP.

Mattel did not consult with the Cherokee Nation on the doll.

"Regrettably, the Mattel company did not work directly with the tribal government's design and communications team to secure the official seal or verify it," the tribe said in a statement. "The printing mistake itself does not diminish what it means for the Cherokee people to see this tribute to Wilma and who she was and what she stood for."

Several Cherokees also criticized Mattel for not consulting with Mankiller's only surviving child, Felicia Olaya, who said she was unaware of the doll until about a week before its public launch.

"I have no issues with the doll. I have no issues with honoring my mom in different ways," said Olaya, who acknowledged she and Soap, her stepfather, are estranged. "The issue is that no one informed me, no one told me. I didn't know it was coming."

Olaya also wonders how her mother would feel about being honored with a Barbie doll.

"I heard her once on the phone saying, 'I'm not Princess Diana, nor am I Barbie,'" Olaya recalled. "I think she probably would have been a little conflicted on that, because my mom was very humble. She wasn't the type of person who had her honorary degrees or awards plastered all over the wall. They were in tubs in her pole barn."

"I'm not sure how she would feel about this," Olaya said.

Still, Olaya said she hopes to buy some of the dolls for her grandchildren and is always grateful for people to learn about her mother's legacy.

"I have a warm feeling about the thought of my granddaughters playing with a Wilma Mankiller Barbie," she said.

Native American News Roundup Nov. 26 - Dec. 2, 2023

Calculating the wage gap for Native American and Native Hawaiian women

The last day of Native American Heritage Month in the United States was also Native Women’s Equal Pay Day, set aside to highlight that Native American and Alaska Native (NA/AN) women working full time, year-round, earn only about 55 cents for every dollar paid to non-Hispanic white men. Those who work part-time or part-year earn an average of 59 cents on the dollar.

These numbers vary by region. The National Partnership for Women and Families (NPWF) reports that on average, a Yup’ik woman in Alaska earns only 42 cents on the dollar. Considering that nearly two-thirds of Indigenous women are the sole breadwinners in their households and that more than four out of five Indigenous women experience violence, stalking or sexual assault in their lifetimes, these numbers are particularly alarming.

NPWF calculates that if these wage gaps were to close for a single year, the average Native woman could save enough money to buy another 32 months of food for her family, pay 19 more months in rent, and pay nearly three years of public university tuition and fees.

Read more:

Controversial hockey helmet fetches high bid at auction

On the National Hockey League’s Native American Heritage Day last Friday, Minnesota Wild hockey goalie Marc-Andre Fleury took to the ice in warmups wearing a mask he commissioned to honor his wife, who is said to be of Indigenous Canadian heritage.

He wore the mask despite threats of an NHL fine. Last summer, the NHL banned so-called “pride jerseys” that visibly recognize LGBTQ+ communities.

Fleury’s mask was designed by Mdewakanton Dakota artist Cole Redhorse Taylor, a member of the Prairie Island Indian Community or PIIC in Minnesota and a descendant of Chief Little Crow.

The helmet includes images of plants and flowers indigenous to Minnesota, the names of Fleury’s children, a quote from his father and the Dakota phrase Mni Sota Makoce, “land where the waters reflect the clouds,” from which the state took its name.

The team put the mask up for auction in support of the Minnesota Wild Foundation and the American Indian Family Center in the city of St. Paul. It sold for a whopping $75,100.

Read more:

Call-in show highlights traditional Indigenous winter homebuilding

This week’s Native America Calling featured a discussion about traditional Indigenous winter housing, built from local resources including wood, snow, mud and straw.

The daily live call-in program available on U.S. and Canadian public radio stations and online included Jesse Jackson, an educator from the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians in Oregon, explaining to host Shawn Spruce (Laguna Pueblo) that because of its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, Oregon winters were wet, and people needed homes which would not only keep them warm but also dry. The answer was to use rot-resistant cedar planks on sites with good drainage.

Solomon Awa (Inupiat) is the Mayor of Iqaluit, the only city in the Canadian territory of Nunavut. He described the challenges of building igloos, domed houses built from blocks of packed snow.

While few Arctic peoples live in igloos anymore, some still construct them while out on hunting trips or when snowmobiles break down and leave them stranded.

“You don't have a blueprint, but make it for the size of your people,” Awa said. “There was the big one that we did not long ago…[it] was about 50 feet diameter probably, almost two-story high.”

To hear more guests talk about their winter building traditions, listen to the full broadcast here: https://www.nativeamericacalling.com/tuesday-november-28-2023-igloos-and-traditional-winter-homes/

The video (below), produced in 2012 by the Pitquhirnikkut Ilihautiniq/Kitikmeot Heritage Society in Nunavut, Canada, shows a group of Inuinnait from the Central Canadian Arctic building an igloo.

- By Dora Mekouar

Busting Myths About the First Thanksgiving

All About America explores American culture, politics, trends, history, ideals and places of interest.

Every year, on the fourth Thursday in November, Americans celebrate Thanksgiving. It's a commemoration of the 1621 harvest feast when the colonists, who came from England, shared a friendly meal with the land's Indigenous people.

In Plymouth, Massachusetts, site of the first Thanksgiving, historians and others try to separate fact from fiction surrounding the legend that grew out of that initial celebratory feast that took place more than 400 years ago.

"The problem with it is that there are so many stereotypes and so much misinformation that's bundled into that story," says Paula Peters, a citizen of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe whose ancestors are believed to have been at the first Thanksgiving. "It's a story that really marginalizes the Wampanoag history."

The pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower in 1620. By their second winter, they were struggling, until the Indigenous people taught them how to plant crops and live off the land.

"When we think about the pilgrims coming over, we forget about the aspect of the Wampanoag people helping them survive that winter, or even navigate this land, or navigate the waters, which is very important," says Wampanoag Tribe member Malissa Costa, who oversees the Native American-themed exhibit at the Plimoth Patuxet Museums.

The living history museum, located a few kilometers from the site of the first Thanksgiving, also features a 17th-century English village. Actors dress up as pilgrims to depict the colonists' way of life, while Thanksgiving traditions are recreated for visitors.

"What the pilgrims are celebrating is literally that they are going to have food. They are not going to starve in the coming year," says Malka Benjamin, director for colonial interpretation and training at the Plimoth Patuxet Museums. "And so, guests are going to be able to help with cooking preparations for the celebration. They might get pulled into a game, a sport ... there's going to be musket firing demonstrations."

It was the sounds of guns going off that prompted Native Americans to investigate, which is how her Wampanoag ancestors came to be at the first Thanksgiving, according to Peters.

"At some point, they decided, 'Oh, this isn't a threat. They're just celebrating their harvest.' And guess what? We're all here now, so, we're all going to eat," says Peters, who used to work at the Plimouth Patuxet Museums.

That part of the story is disputed by Peters' former colleague, Richard Pickering, chief historian at the living history museum, who says that theory was discussed, but then discarded, by the museum.

The conflicting viewpoints underscore the reality that no one really knows exactly what happened at the first Thanksgiving. There are almost no firsthand accounts of the event, but there are references to a "special celebration" of the successful harvest, which included Wampanoag leader Massasoit and about 90 of his people, which included women, according to Pickering.

"For three days, we entertained and feasted," pilgrim Edward Winslow wrote in a letter to a friend in 1621. Winslow attended the harvest celebration.

"Ultimately, what happens in Plymouth in the fall of 1621 is the highest level of diplomacy," says Pickering, adding that the shared meal was a product of the alliance between the newcomers and the Native people.

"It is their willingness to show them their ways that saves the English that second year. So, we should not be projecting any kind of distrust, animus, on that event. But we should recognize that their children and their grandchildren could not sustain it," he said.

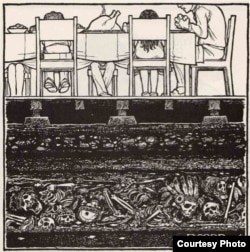

About 90% of the Native population was eventually wiped out by diseases that came with the Europeans. And the respect the pilgrims initially showed the Native people eventually gave way to disdain and dehumanization.

"As the English population grows from those 52 English men, women and children that survived the first winter to the 25,000 or more that are here 20 years later, Native people are seen as being in the way of the commodities that the English want," Pickering says. "They want their land. They want them off that land. And so, you see a changing attitude from one of admiration to one of stereotyping and derision. And it's that kind of thought that enables them to want to push them off the land with no sense of guilt."

The pilgrims originally came to America in search of religious freedom but apparently not for all, says Peters.

"They sacrificed so much for religious freedom, but they didn't offer that same grace to the Indigenous people who lived here to begin with," she says.

Harvest meal

Today, Americans often eat traditional Thanksgiving foods that include turkey, stuffing, sweet and mashed potatoes and pumpkin pie. As to what was at the original three-day feast, the museum has a display of the foods that were probably eaten at the 1621 meal.

"You have roast turkey, roast goose, and you'll see all of the classic corn, beans and squash. There's maize, beans and squash," says Pickering, pointing out the foods in a display case. "And also, the standing dish of New England, stewed pumpkin, mussels, to represent all the shellfish that was eaten."

It's believed the Wampanoag brought deer they'd hunted.

"And there probably would be some cranberries, because that was the fruit of the season," Peters says.

Into the future

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe has begun initial proceedings to establish their own living history museum.

The town of Mashpee, located about 43 kilometers from Plymouth, is negotiating the potential transfer of three parcels of land to the tribe for a traditional Wampanoag village and living history museum.

Costa, who oversees the similar effort at the Plimoth Patuxet Museums, is keen for visitors to know that Native Americans shouldn't be relegated to the past.

"The main thing I want them to learn is that Wampanoag people are still here," Costa says. "I want them to think of Wampanoag people as not just in the past — or even Indigenous people as in the past — but as in the present still making their way, still teaching the public."

Native Americans Regard Thanksgiving With Mixed Emotions

Each year on the last Thursday of November, families in the United States gather to celebrate Thanksgiving. It was originally intended as a day of prayer and gratitude — not just for good harvests but for a leader's good health or success in battle.

Today, the holiday revolves around a sentimentalized retelling of the 1620 landing of Puritan refugees at Plymouth, Massachusetts, and the harvest feast they shared with local Wampanoags.

That version omits the fact that 17 years later, Puritans would set fire to a fortified Pequot village, burning men, women and children alive.

Today, Native Americans regard Thanksgiving with mixed emotions.

"Native Americans eat and watch football just like other Americans," said Shawna Shale, a Quinault woman living in Fergus Falls, Minnesota. "But for some, it is a reminder of a dark past that is hard to celebrate."

She admits that she often wonders how differently life would have turned out if the Wampanoag tribe decided not to ally itself with the Plymouth pilgrims.

Thanksgiving memories

Many Native Americans never heard of Thanksgiving until they were sent to boarding school.

"[I am] a second-generation turkey eater, after my parents," said artist Roberta Begay, a Diné (Navajo) citizen living in Albuquerque, New Mexico. "It's a boarding school tradition. I never understood it as anything other than a time for a family gathering, eating and helping my grandparents by hauling water or going out for firewood."

Phoenix, Arizona, resident Reva Stewart, also Diné, experienced her first Thanksgiving in a Christian boarding school. She was 4 years old.

"We were given Thanksgiving dinner with the idea that we should be grateful that we were saved," she said. "Today, my family celebrates being together as a family, and we teach our children the traditional ways and not the colonizers' [version] of what happened in the past."

A sad anniversary

Amanda Takes War Bonnet is an Oglala Lakota journalist working as a public education specialist with a South Dakota nonprofit group devoted to ending violence against Indigenous women.

"My mother would always have a nice meal on Thanksgiving, with pies and everything homemade," she recalls. "It also meant hunting season had started, so the meal was held after the guys [came back from] hunting."

Thanksgiving now holds little meaning for her.

"Some years back, my son brought this huge turkey from his work to share with family. I didn't estimate the cooking time right, so we had to start the meal without it," she said.

"My son died in front of us from a heart attack," she said. "That big bird dried up in the oven, forgotten."

She never roasted another turkey after that.

"Maybe someday, we will heal, but for now, 'Turkey Day' is just a great holiday to not work and relax with a prime rib roast."

'A golden opportunity'

Oglala Lakota journalist James Giago Davies grew up in Rapid City, South Dakota, where churches and charity groups gave out free turkeys and all the "fixings."

"We were a poor Native family, struggling to survive," he said. "Thanksgiving was a golden opportunity to get extra food and have a good meal. We never thought of it beyond that immediate pressing reality, and I don't know of any families from my 'rez' who did. Maybe it is different now."

David Cornsilk, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation from Tahlequah, Oklahoma, grew up in a traditional household where Thanksgiving was never celebrated.

"My dad opposed it, saying there was nothing Indian people had to celebrate in America," Cornsilk said. "But he never talked about history. It was not until high school that I learned the truth about Indigenous history and then only because I had become a voracious reader of history."

Years later, Cornsilk married into a Cherokee family he describes as the "polar opposite."

"Where we were traditional, they were Christian. Where we rejected Thanksgiving, they embraced it and had a huge feast with a large family gathering," he said.

It is a tradition he has passed on to his children and grandchildren.

"The difference will be that my children and grandchildren know their history," he said. "We give thanks for our blessings and share our bounty in a land we love with the people we love."

'Takesgiving'

Lynn Eagle Feather, a Sicangu Lakota living in Denver, Colorado, says she lost her son to police violence in July 2015 and has been seeking justice ever since.

"Thanksgiving?" she asks. "You mean 'Takesgiving.'"

She plans to spend the holiday demonstrating outside of a Denver hospital where staff cut off the waist-length hair of 65-year-old Oglala Lakota elder Arthur Janis, without his or his family's permission, while he was undergoing medical treatment.

"This is Native American Heritage Month," Eagle Feather said, "and our people are still suffering."

Solar Panels Over Canals in Gila River Indian Community Will Help Save Water

In a move that may soon be replicated elsewhere, the Gila River Indian Community recently signed an agreement with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to put solar panels over a stretch of irrigation canal on its land south of Phoenix.

It will be the first project of its kind in the United States to break ground, according to the tribe’s press release.

“This was a historic moment here for the community but also for the region and across Indian Country,” said Gila River Indian Community Governor Stephen Roe Lewis in a video published on X, formerly known as Twitter.

The first phase, set to be completed in 2025, will cover 1,000 feet of canal and generate one megawatt of electricity that the tribe will use to irrigate crops, including feed for livestock, cotton and grains.

The idea is simple: install solar panels over canals in sunny, water-scarce regions where they reduce evaporation and make renewable electricity.

“We’re proud to be leaders in water conservation, and this project is going to do just that,” Lewis said, noting the significance of a Native, sovereign, tribal nation leading on the technology.

A study by the University of California, Merced estimated that 63 billion gallons of water could be saved annually by covering California’s 4,000 miles of canals. More than 100 climate advocacy groups are advocating for just that.

Researchers believe that much of the installed solar canopies would additionally generate a significant amount of electricity.

UC Merced wants to hone its initial estimate and should soon have the chance. Not far away in California's Central Valley, the Turlock Irrigation District and partner Solar AquaGrid plan to construct 1.6 miles (2.6 kilometers) of solar canopies over its canals beginning this spring and researchers will study the benefits.

Neither the Gila River Indian Community nor the Turlock Irrigation District are the first to implement this technology globally. Indian engineering firm Sun Edison inaugurated the first solar-covered canal in 2012 on one of the largest irrigation projects in the world in Gujarat state. Despite ambitious plans to cover 11,800 miles (19,000 kilometers) of canals, only a handful of small projects ever went up, and the engineering firm filed for bankruptcy.

High capital costs, clunky design and maintenance challenges were obstacles for widespread adoption, experts say.

But severe, prolonged drought in the western U.S. has centered water as a key political issue, heightening interest in technologies like cloud seeding and solar-covered canals as water managers grasp at any solution that might buoy reserves, even ones that haven't been widely tested, or tested at all.

Still, the project is an important indicator of the tribe's commitment to water conservation, said Heather Tanana, a visiting law professor at the University of California, Irvine and citizen of the Navajo Nation. Tribes hold the most senior water rights on the Colorado River, though many are still settling those rights in court.

“There's so much fear about the tribes asserting their rights and if they do so, it'll pull from someone else's rights,” she said. The tribe leaving water in Lake Mead and putting federal dollars toward projects like solar canopies is “a great example to show that fear is unwarranted.”

The federal government has made record funding available for water-saving projects, including a $233 million pact with the Gila River Indian Community to conserve about two feet of water in Lake Mead, the massive and severely depleted reservoir on the Colorado River. Phase one of the solar canal project will cost $6.7 million and the Bureau of Reclamation provided $517,000 for the design.

Native American News Roundup November 12-18, 2023

These are some of the Native American-related stories that made headlines this week:

Oklahoma lawmaker, union boss, come close to blows in Senate hearing room

Oklahoma Republican Senator Markwayne Mullin, a former mixed martial arts fighter and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, says he isn’t sorry for challenging Teamster president Sean O’Brien to a fist fight during a Senate committee hearing on Tuesday.

Independent Senator Bernie Sanders, chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, was forced to intervene.

This wasn’t the pair’s first clash. During a committee hearing in March, O’Brien and Mullin shouted at each other. That led to a series of angry exchanges on social media platform X. In June, O’Brien challenged Mullin to a fight.

“You know where to find me. Anyplace, anytime, cowboy,” O’Brien said.

Mullin responded on X:

That fight never took place.

“People ask me today is this becoming of a U.S. senator,” Mullin told FOX News. “In Oklahoma, you don’t run your mouth like that, and if you do run your mouth like that, you’re expected to be called out on it.”

Read more:

Feds to fund Native Hawaiian-led climate resilience program

Democratic Senator Brian Schatz, chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, this week announced $20 million in funding for the Kapapahuliau Climate Resilience Program to help the Native Hawaiian community mitigate the challenges of climate change.

“Through the Kapapahuliau Climate Resilience Program, the federal government is directly funding Native Hawaiian-led climate solutions for the first time ever,” Schatz said. “This $20 million down payment — part of the Inflation Reduction Act’s historic investment in climate action — recognizes the critical role of the Native Hawaiian Community in charting a path towards a sustainable, climate resilient future in Hawaii and beyond.”

The Fifth U.S. National Climate Assessment, released earlier this week, says Indigenous peoples and their knowledge will be central to the resilience of Hawaiian and Pacific Island communities addressing changing climate.

Read more:

USDA to fund traditional Native American forestry in Oregon

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service has awarded $9.23 million to the Oregon Agricultural Trust (OAT) and its partners for projects using traditional Native American land management practices to restore Oregon’s oak habitat.

Long before Europeans set foot in North America, Indigenous communities used fire to clear land for agriculture or roadways, rejuvenate plants, eradicate pests and avoid devastating wildfires.

Since 2000, wildfires have become larger and more frequent across the United States, and a growing number of localities have begun to embrace so-called “cultural burns” as part of the solution.

“Use of cultural fire, traditional fire, on the landscape usually entails people who are trained or have the wildfire qualifications,” said Ka-Voka Jackson, program manager for the EcoStudies Institute, an OAT partner. “That usually entails fire trucks or water resources, the use of drip torches, other hand tools.”

The project will work with tribes to protect Oregon’s iconic oak trees. It will also give Native Americans access to oak forests for cultural use and environmental stewardship.

Read more:

Confusion in Oklahoma over state, tribal vehicle law

Tribal leaders in Oklahoma are outraged after a state police officer stopped an Otoe-Missouria tribal citizen for speeding and gave her two tickets: one for speeding and a another for failing to pay state motor vehicle taxes because she did not live on tribal land.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1993 that Indigenous Oklahomans could register a vehicle through their tribe if they reside inside reservation boundaries. The ruling also says the state doesn't have the authority to tax tribal citizens living on reservations.

Three of the 39 tribes in Oklahoma — the Cherokee, Chickasaw and Choctaw — have compacts with the state that allow tribe members to drive with tribal car tags wherever they live.

Members of the other 36 tribes that do not have compacts — including the Otoe-Missouria — are supposed to register their vehicles with the state.

Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt, says his main concern is that some tribal governments don't share vehicle registration information with the Department of Public Safety, making it a “public safety issue that puts law enforcement and others at risk.”

Otoe-Missouria Chairman John Shotton suggests the state has not enforced the law until now.

“After over 20 years of cooperation between the State and Tribes regarding vehicle tag registration, it appears the State has altered its position of understanding concerning tribal tags,” Shotton said in a statement. “This change was made without notice or consultation with all Tribes that operate vehicle tag registration.”

Read more:

Judge Rules Against Tribes in Fight Over Nevada Lithium Mine

A federal judge in Nevada has dealt another legal setback to Native American tribes trying to halt construction of one of the biggest lithium mines in the world.

U.S. District Judge Miranda Du granted the government's motion to dismiss their claims the mine is being built illegally near the sacred site of an 1865 massacre along the Nevada-Oregon line.

But she said in last week's order the three tribes suing the Bureau of Land Management deserve another chance to amend their complaint to try to prove the agency failed to adequately consult with them as required by the National Historic Preservation Act.

"Given that the court has now twice agreed with federal defendants (and) plaintiffs did not vary their argument ... the court is skeptical that plaintiffs could successfully amend it. But skeptical does not mean futile," Du wrote Nov. 9.

She also noted part of their case is still pending on appeal at the 9th U.S Circuit Court of Appeals, which indicated last month it likely will hear oral arguments in February as construction continues at Lithium Nevada's mine at Thacker Pass about 370 kilometers northeast of Reno.

Du said in an earlier ruling the tribes had failed to prove the project site is where more than two dozen of their ancestors were killed by the U.S. Cavalry Sept. 12, 1865.

Her new ruling is the latest in a series that have turned back legal challenges to the mine on a variety of fronts, including environmentalists' claims it would violate the 1872 Mining Law and destroy key habitat for sage grouse, cutthroat trout and pronghorn antelope.

All have argued the bureau violated numerous laws in a rush to approve the mine to help meet sky-rocketing demand for lithium used in the manufacture of batteries for electric vehicles.

Lithium Nevada officials said the $2.3 billion project remains on schedule to begin production in late 2026. They say it's essential to carrying out President Joe Biden's clean energy agenda aimed at combating climate change by reducing dependence on fossil fuels.

"We've dedicated more than a decade to community engagement and hard work in order to get this project right, and the courts have again validated the efforts by Lithium Americas and the administrative agencies," company spokesperson Tim Crowley said in an email to The Associated Press.

Du agreed with the government's argument that the consultation is ongoing and therefore not ripe for legal challenge.

The tribes argued it had to be completed before construction began.

"If agencies are left to define when consultation is ongoing and when consultation is finished ... then agencies will hold consultation open forever — even as construction destroys the very objects of consultation — so that agencies can never be sued," the tribal lawyers wrote in recent briefs filed with the 9th Circuit.

Will Falk, representing the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony and Summit Lake Paiute Tribe, said they're still considering whether to amend the complaint by the Dec. 9 deadline Du set, or focus on the appeal.

"Despite this project being billed as `green,' it perpetrates the same harm to Native peoples that mines always have," Falk told AP. "While climate change is a very real, existential threat, if government agencies are allowed to rush through permitting processes to fast-track destructing mining projects like the one at Thacker Pass, more of the natural world and more Native American culture will be destroyed."

The Paiutes call Thacker Pass "Pee hee mu'huh," which means "rotten moon." They describe in oral histories how Paiute hunters returned home in 1865 to find the "elders, women, and children" slain and "unburied and rotting."

The Oregon-based Burns Paiute Tribe joined the Nevada tribes in the appeal. They say BLM's consultation efforts with the tribes "were rife with withheld information, misrepresentations, and downright lies."

Native American Advocates Seek Plan to Handle Missing and Murdered Cases

Advocates are calling out New Mexico's Democratic governor for disbanding a task force that was charged with crafting recommendations to address the high rate of killings and missing person cases in Native American communities.

The Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women said in a statement Thursday that dissolving the panel of experts only helps to perpetuate the cycles of violence and intergenerational trauma that have created what many have deemed as a national crisis.

Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham's office argues that the task force fulfilled its directives to study the scope of the problem and make recommendations and that the state remains committed to implementing those recommendations.

The push by the advocates comes just weeks after a national commission delivered its own recommendations to Congress and the U.S. Justice and Interior departments following hearings across the country and promises by the federal government to funnel more resources to tackling violence in Native American communities.

U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who is from Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, said earlier this month that lives will be saved because of the commission's work.

"Everyone deserves to feel safe in their community," Haaland said when the recommendations were announced. "Crimes against Indigenous peoples have long been underfunded and ignored, rooted in the deep history of intergenerational trauma that has affected our communities since colonization."

Her agency and the Justice Department are mandated to respond to the recommendations by early next year.

Almost 600 people attended the national commission's seven field hearings, with many giving emotional testimony.

Members of the Not Invisible Commission have said they hope the recommendations are met with urgency.

"With each passing day, more and more American Indian and Alaska Native persons are victimized due to inadequate prevention and response to this crisis," the commission said in its report.

Still, advocates in New Mexico say more work needs to be done to address jurisdictional challenges among law enforcement agencies and to build support for families.

"It's essential to recognize that MMIWR is not a distant issue or statistic; these are real-life stories and struggles faced by Indigenous families today. The impact has forced these families to adjust their way of life, advocate for themselves, deplete their savings, and endure stress-induced physical and mental illnesses," the Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women said.

The organization wants state officials to outline a clear plan for advancing New Mexico's response to the problem.

The New Mexico Indian Affairs Department said Thursday it is developing a dedicated web page and is planning regular meetings and other events aimed at bringing together families with tribal partners and local, state and federal officials.

Aaron Lopez, a spokesperson for the agency, said the task force's work remains foundational for the state in determining the best strategies for curbing violence against Native Americans.

The New Mexico Attorney General's Office also has a special agent who has been working with authorities to help recover people on the FBI's list of those verified as missing from the state and the Navajo Nation, which covers parts of New Mexico, Arizona and Utah. As of October, there were about 190 names on the list.

While budget recommendations are still being hashed out for the next fiscal year, the Indian Affairs Department already is asking for four new full-time staffers who would be dedicated to helping advance the state's response plan.

James Mountain, head of the department, told lawmakers during a recent hearing that the positions are "absolutely needed" to carry forward the state's work given that the agency serves numerous tribal nations and pueblos.

Native American News Roundup Nov. 5-11, 2023

Mattel honors Cherokee rights icon Wilma Mankiller

Citizens of the Cherokee Nation are delighted with the Mattel toy company’s release this week of new doll in its Barbie Inspiring Women series: Wilma Mankiller, the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation and a powerful social activist.

“When Native girls see it, they can achieve it, and Wilma Mankiller has shown countless young women to be fearless and speak up for Indigenous and human rights,” Cherokee Nation principal chief Chuck Hoskins Jr. said in a written statement. “She not only served in a role dominated by men during a time that tribal nations were suppressed, but she led. … She truly exemplifies leadership, culture and equality, and we applaud Mattel for commemorating her in the Barbie Inspiring Women Series.”

“We worked with Charlie Soap, Wilma’s husband, and Kristina Kiehl, Wilma’s longtime friend [who] gave us insight to not just Wilma’s brilliant career and achievements, but also sentimental insight like Wilma almost never wore heels and liked to get her nails done. So, the Wilma Barbie is wearing flats and has pink painted nails,” the doll’s designer Carlyle Nuera posted on Facebook.

By Thursday, the doll had sold out.

2020 Census: Native American/Alaskan Population Nearly Doubles

The U.S. Census Bureau has released new statistics for the American Indian and Alaska Native populations showing that they are one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States.

In 2010, 5.2 million people in the United States identified as American Indian and Alaska Native population. A decade later, 9.7 million claimed Native American or Alaska Native identities.

Among the people who specified a tribal affiliation, Cherokees represent the largest American Indian population alone or in any combination population group in the United States, with 1,513,326 people. The Navajo Nation was the most common American Indian alone, with 315,086 people.

Among the 171,000 respondents who identified with a specific Alaska Native tribe, Yup’ik (Yup’ik Eskimo) came in as the largest Alaska Native alone group in the U.S., with 9,026 people. Tlingit was the largest Alaska Native alone or in any combination group with 22,601 people.

It should be noted, however, that with more and more Americans claiming Indigenous ancestors based on family lore or “Pretendianism,” these numbers may be hard to verify.

See more:

City of Sacramento honors Northern California tribes

Hundreds gathered in Sacramento on Tuesday for the unveiling of a new, 8-foot-tall bronze statue of Miwok leader and cultural preservationist William J. Franklin Sr.

The statue replaces a statue of Franciscan missionary Junipero Serra, the man who 300 years ago founded nearly two dozen missions, aiming to convert and “civilize” California Indians and give Spain a foothold in the region. Protesters tore down that statue in July 2020.

To learn more about Franklin Sr., read or listen to his interview with Elizabeth McKee, conducted as part of the Sacramento Ethnic Communities Survey Collection.

Indigenous drag queens combine drag queens and glitter

More than a dozen U.S. states have enacted or introduced legislation to restrict drag shows. It is the product of socially conservative momentum against events where performers who are mostly men dress mostly as women. Gustavo Martínez Contreras reports for VOA from a show in New Mexico that involves a unique all-Indigenous cast called “LaLa Land Back” and blends the camp of drag with Native American culture.

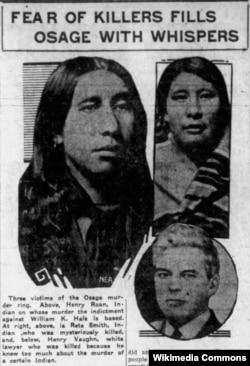

Osage Tribe Members Speak Their Minds About ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’

Martin Scorsese's "Killers of the Flower Moon” explores the “Reign of Terror,” a dark period in 1920’s Oklahoma when white cattle rancher William Hale orchestrated the murders of Osage tribe members to take land rich with oil.

Hollywood has a long history of misrepresenting Native Americans in film, and Osages were skeptical that Scorsese could do any differently. In July 2019, the famed director met with Osage Nation Principal Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear to discuss the tribe’s involvement in the film. The following October, he addressed more than 150 Osage tribe members who worried about how their ancestors and culture would be portrayed.

“My heart is in the right place,” Scorsese told them. “We won’t be finished with it until it’s right, I can promise you that.”

But did he deliver on his pledge? Among the “Reign of Terror” victims was Henry Roan, shot dead in early 1923. His great grandson, former Osage Chief Jim Gray, attended the meeting with Scorsese.

“When I had the chance to speak, I told him that the culture and language, traditions of the tribe, all these things that make us who we are today are not in the FBI files, and you're not going to find them in the book [of the same name by David Grann]. You'll find them in this room,” Gray told VOA. “We got the benefit of his willingness to listen and incorporate much of what he heard.”

‘Evil white characters’

Grann’s 2017 book reads like a detective novel, but after hearing from the Osage, Scorsese rewrote the script around Ernest Burkhart — nephew of the rancher Hale, ruthless mastermind behind the Osage murders — who married into an Osage family and eventually attempted to poison his wife, Mollie.

"The heart of the entire situation is love, the trust that goes with love, and then this extraordinary betrayal,” Scorsese told CBS News.

Christopher Cote, who served as the film’s language consultant, was unconvinced, telling reporters, “when somebody conspires to murder your entire family, that’s not love.”

George “Tink” Tinker, professor emeritus at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, and a citizen of the Osage Nation, laughed before giving his opinion of the film.

“He did the best job any white man in this day and age could have done,” Tinker said. “Is it a movie about the Osages? No. It’s about two evil white characters who were busy murdering Osages.”

Hale is played by Robert DeNiro, while Burkhart is played by Leonardo DiCaprio.

“When you have big stars like that, you can't make the movie about these minor characters surrounding and supporting the narrative, namely the Osages,” Tinker added. “Even the character of Mollie Burkhart, who has more of a role than the other Osages, is silent throughout much of the film.”

Otoe-Missouria/Osage attorney Wilson Pipestem turned to Facebook, urging critics to be “gentle” with their words:

Shot on location in Oklahoma, the film’s supporting cast includes dozens of Osage actors in key parts.

Native American News Roundup Oct. 29 - Nov. 4, 2023

This week’s roundup focuses on a story that continues to dominate headlines:

The Buffy Sainte-Marie Scandal: Is she Indigenous?

Since bursting onto the folk music scene in the early 1960s, singer/ songwriter/Indigenous activist Buffy Sainte-Marie has claimed to have been born Beverley Sainte-Marie to an unknown Cree mother on the Piapot First Nation Reserve in the western Canadian province of Saskatchewan and adopted out to a Mi’kmaq (Micmac) family in New England.

There have been questions about inconsistencies in her account over the years.

Ontario’s Sault Times in July 1963, for example, identified her as Mi’kmaq from Canada’s Maritime provinces.

Detroit’s Free Press in October 1963 stated, “Buffy was born a Micmaq Indian in Maine and grew up with a part white, part Micmac family.”

Saskatoon’s Star-Phoenix in March 1966 identified her as a “full blooded Cree” brought up by a “Micmac Indian couple.”

Given the singer’s iconic status, no one publicly challenged her genealogy.

Until now.

Last week, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s investigative series Fifth Estate revealed results of a year-long investigation claiming that her she was born Beverley Jean Santamaria in Stoneham, Massachusetts in 1941 to a white couple, Albert and Winifred Santamaria, and as an adult was adopted into a Piapot Cree family.

The report claims that when her brother Alan Santamaria moved to reveal her deception, she threatened him with allegations of sexual abuse.

Last week’s broadcast stunned Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities on both sides of the U.S.- Canada border.

The Indigenous Women’s Collective in Canada issued a statement calling for Sainte-Marie’s 2018 Juno music award to be rescinded.

Canadian music historian John Einarson, who wrote a 2006 documentary called Buffy Sainte-Marie: A Multimedia Life, expressed his disappointment on Facebook.

“I feel a sense of betrayal that Buffy engaged in a deceit for decades and after so much praise for her as an Indigenous Canadian,” he posted. “There have been ample opportunities in her 60-year career to ‘come clean’ on her falsehoods but instead she continually modified her ‘story’, doubling down, obfuscating and waffling. That, to me, is unforgiveable and all her great works are stained now by that.”

Others have condemned the CBC investigation.

“For some inexplicable reasons...some Native people seem to be questioning her truth," Native American land rights activist Winona LaDuke wrote on Facebook.. Why that would occur baffles me. Time to stop hating our own...time to quit witch hunting. Time to respect and love our people...time to move towards a real healing and survival.

One day before the report aired, Buffy Sainte-Marie posted a video statement on Facebook denying the allegations.

“I’m lucky to have had two families to love: a growing up family who were wonderful and my Piapot family, who are also wonderful,” she said. “There are also many things I don't know which I've always been honest about. I don't know where I'm from, who my birth parents are or how I ended up a misfit in a typical white Christian New England town.”

Facts of her adoption

No one disputes her custom adoption into a Piapot Cree family.

According to accounts in Saskatchewan’s Leader Post newspaper and elsewhere, in early August 1962, Sainte-Marie, then 21, attended the Wikwemikong Pow Wow on Ontario’s Manitoulin Island, where she met and was subsequently adopted by Emile and Clara Piapot, something the singer called the “highlight of her life.”

The elder Piapots are no longer living, but younger family members have come out to defend Sainte-Marie.

“Our grandparents filled the holes in their hearts by adopting Buffy after losing several children to illness and disease …” Debra and Ntawnis Piapot said in a written statement. “Buffy is our family …To us, that holds far more weight than any paper documentation or colonial record keeping ever could.”

Anishinaabekwe musician and activist ShoShona Kish told CBC that she isn’t interested in debating Sainte-Marie’s indigeneity.

“We are sovereign nations, and we can decide our own citizenship,” she said.

Others disagree, citing differences between traditional or "customary" adoptions and legal adoptions.

VOA reached out to Kim TallBear, a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton tribe in South Dakota and a professor of Native Studies at the University of Alberta.

“There are some First Nations bands in Canada that do allow legally adopted children to enroll in the band, and in the United States, enrolling spouses and legally adopted children in tribes was very common pre-World War Two,” she said.

But Sainte-Maries’ adoption was purely ceremonial.

“These don’t make people tribe members or First Nation citizens,” TallBear explained. “Tribal rules around citizenship and membership are very legalistic, like the rules around U.S. and Canadian citizenship, and they rely on documentation.”

For his part, Piapot First Nation acting chief Ira Lavallee told CBC he understands people’s sense of betrayal.

"When it comes to Buffy specifically, we can't pick and choose which part of our culture we decide to adhere to … We do have one of our families in our community that did adopt her. Regardless of her ancestry, that adoption in our culture to us is legitimate."

Ohio's Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks Mark UNESCO World Heritage Designation

For 400 years, Indigenous North Americans flocked to a group of ceremonial sites in what is present-day Ohio to celebrate their culture and honor their dead. On Saturday, the sheer magnitude of the ancient Hopewell culture's reach was lifted up as enticement to a new set of visitors from around the world.

"We stand upon the shoulders of geniuses, uncommon geniuses who have gone before us. That's what we are here about today," Chief Glenna Wallace, of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, told a crowd gathered at the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park to dedicate eight sites there and elsewhere in southern Ohio that became UNESCO World Heritage sites last month.

She said the honor means that the world now knows of the genius of the Native Americans, whom the 84-year-old grew up seeing histories, textbooks and popular media call "savages."

Wallace commended the innumerable tribal figures, government officials and local advocates who made the designation possible, including late author, teacher and local park ranger Bruce Lombardo, who once said, "If Julius Caesar had brought a delegation to North America, they would have gone to Chillicothe."

"That means that this place was the center of North America, the center of culture, the center of happenings, the center for Native Americans, the center for religion, the center for spirituality, the center for love, the center for peace," Wallace said. "Here, in Chillicothe. And that is what Chillicothe represents today."

The massive Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks — described as "part cathedral, part cemetery and part astronomical observatory" — comprise ancient sites spread across 150 kilometers south and east of Columbus, including one located on the grounds of a private golf course and country club. The designation puts the network of mounds and earthen structures in the same category as wonders of the world including Greece's Acropolis, Peru's Machu Picchu and the Great Wall of China.

The presence of materials such as obsidian, mica, seashells and shark teeth made clear to archaeologists that ceremonies held at the sites some 2,000 to 1,600 years ago attracted Indigenous peoples from across the continent.

The inscription ceremony took place against the backdrop of Mound City, a sacred gathering place and burial ground that sits just steps from the Scioto River. Four other sites within the historical park — Hopewell Mound Group, Seip Earthworks, Highbank Park Earthworks and Hopeton Earthworks — join Fort Ancient Earthworks & Nature Preserve in Oregonia and Great Circle Earthworks in Heath to comprise the network.

"My wish on this day is that the people who come here from all over the world, and from Ross County, all over Ohio, all the United States — wherever they come from — my wish is that they will be inspired, inspired by the genius that created these, and the perseverance and the long, long work that it took to create them," Republican Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine said. "They're awe-inspiring."

Nita Battise, tribal council vice chair of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, said she worked at the Hopewell historical park 36 years ago — when they had to beg people to come visit. She said many battles have been won since then.

"Now is the time, and to have our traditional, our ancestral sites acknowledged on a world scale is phenomenal," she said. "We always have to remember where we came from, because if you don't remember, it reminds you."

Kathy Hoagland, whose family has lived in nearby Frankfort, Ohio, since the 1950s, said the local community "needs this," too.

"We need it culturally, we need it economically, we need it socially," she said. "We need it in every way."

Hoagland said having the eyes of the world on them will help local residents "make friends with our past," boost their businesses and smooth over political divisions.

"It's here. You can't take this away, and so, therefore, it draws us all together in a very unique way," she said. "So, that's the beauty of it. Everyone lays all of that aside, and we come together."

National Park Service Director Chuck Sams, the first Native American to hold that job, said holding up the accomplishments of the ancient Hopewells for a world audience will "help us tell the world the whole story of America and the remarkable diversity of our cultural heritage."