Native Americans

- By Dora Mekouar

Why US Army Helicopters Are Named After Native Americans

All About America explores American culture, politics, trends, history, ideals and places of interest.

Apache. Lakota. Chinook. Iroquois.

These are not only Native American tribes that once fought for their land against the U.S. military. They are also the names of U.S. Army helicopters.

The convention of naming choppers after America’s Indigenous people is believed to date back to 1947. Army General Hamilton Howze reportedly wasn’t thrilled with Hoverfly and Dragonfly — the names of the first two Army helicopters — and ordered some changes.

“He wanted to name them after something that was fast-moving, militarily strong and had some kind of connection to American military history,” says David Silbey, a military historian at Cornell University. “And he thought of the Native American warriors of the 19th century — the Apache, the Lakota and all those folks. And so, he started that tradition of naming Army helicopters after Native American tribes.”

An Army regulation created in 1969 codified this naming protocol. Name suggestions were to be provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Silbey says required naming regulations no longer exist, but certain military naming traditions have continued.

For example, the Lakota helicopter was named as recently as 2012 in honor of the Lakota tribe of the Great Sioux Nation in North and South Dakota. That same year, Lakota elders blessed two Lakota choppers at the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota.

“I think the idea of naming weapons and ships and planes is a good one as a way of invoking the history, the tradition, the ethos of the military,” Silbey says. “It's a way of invoking the long history of the United States and the U.S. military. And sometimes even including the folks we were fighting against, who we've now come to peace with, as is the case with Army helicopters.”

Since World War II, Army tanks have been named after generals. There’s the Sherman tank, named after Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman, and the Abrams tank, named for Vietnam-era General Creighton W. Abrams.

Two Army missiles named after venomous snakes are the Titan and the Sidewinder.

“The [sidewinder snake] actually has the ability to sense infrared heat. There’s a thing in its snout that senses heat, and that's how it targets its prey,” Silbey says. “And that's how the missile guides itself — it hones in on the infrared heat of a jet engine. So, there's that nice little actual connection to nature in the name.”

But other Army missiles are named the Falcon, Sparrow and Harpoon, which highlights how military naming protocols can sometimes be all over the place.

However inconsistent, some naming traditions continue across the U.S. military, according to Silbey. The secretary for each service, whether it’s the Marines, Air Force, Army or Navy, has the final say on naming equipment and weapons.

A report by the Congressional Research Service outlines how naming Navy vessels has evolved over time.

“Attack submarines, for example, were once named for fish, then later for cities and most recently [in most cases] for states, while cruisers were once named for cities, then later for states, and most recently for battles,” writes report author Ronald O'Rourke, a naval affairs specialist. “State names, to cite another example, were once given to battleships, then later to nuclear-powered cruisers and ballistic missile submarines, and most recently to [in most cases] Virginia-class attack submarines.”

The United States doesn’t build battleships anymore, but when it did, the vessels were named after U.S. states. And for more than 200 years, there’s always been a Navy ship in the fleet called the USS Enterprise.

Of the Navy’s 15 most recently named aircraft carriers, two are named for members of Congress, and 10 have been named for past presidents, O'Rourke writes in the report. But none of those were named for presidents who were Democrats.

“The last Democratic president to have a carrier named after him is the John F. Kennedy. There’s no Barack Obama. There's no Bill Clinton. There's no Jimmy Carter. There's no Lyndon Johnson,” Silbey says. “There's a Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush. … It's getting a little obvious that they're not naming them after Democratic presidents.”

There are some names that can go horribly wrong. Silbey points to the World War II-era ships designed to carry ammunition and explosives. Many of the ships in this class were named after volcanoes, and one of the vessels exploded in 1944, killing about 400 people.

“I think a way that the military has gone wrong with naming conventions has been that tendency to name things after Confederate generals, political figures, Confederate victories,” Silbey says. “The Confederates were traitors to the United States, traitors to the United States military, and naming a military weapon, installation, ship, plane after someone like Robert E. Lee, who betrayed his country, is/was the wrong choice. And I'm glad it's being fixed.”

The Army has renamed several bases that were initially named after Confederates.

The newest branch of the military, the Space Force, which is tasked with conducting military operations in outer space, hasn’t named any equipment yet. However, members of that branch of the nation's armed forces are currently called guardians.

Oklahoma's Oldest Native American School Threatened by Debts, Disrepair

The hallways of Bacone College are cold and dark. In the main hall, there are no lectures to be heard, only the steady hum of the space heater keeping the administrative offices warm.

Students aren't attending classes here this semester but work still needs to be done. In the college’s historic buildings, there are leaks to plug, mold to purge and priceless works of Native American art to save from ruin. Not to mention devising a plan to keep the college from shuttering for good. It’s a daunting task for the nine remaining employees.

But on this rainy December morning, the college's president is running a DoorDash order. “If we have the money, we can pay,” Interim President Nicky Michael said regarding salaries.

Founded in 1880 as a Baptist missionary college focused on assimilation, Bacone College transformed into an Indigenous-led institution that provided an intertribal community, as well as a degree. With the permission of the Muscogee Nation Tribal Council, Bacone's founders used a treaty right to establish the college at the confluence of three rivers, where tribal nations had been meeting for generations.

Throughout the 20th century, the center of this was Bacone’s Native American art program, which produced some of the most important Indigenous artists of their time, including Woody Crumbo, Fred Beaver, Joan Hill and Ruthe Blalock Jones.

They and their contemporaries pushed the boundaries of what was considered “Native American art.” During a period of intense hostility against tribal sovereignty by the U.S., Bacone became defined by the exchange of ideas its Native faculty and students created and represented a new opportunity for Indigenous education and academic thought.

“Bacone was the only place in the world where that could happen for Native people,” said Robin Mayes, a Cherokee and Muscogee man who attended Bacone in the ’70s and taught silversmithing there in the ’90s. “It’s a tragedy to think that it’s going to be discontinued.”

For decades, the college has been plagued by poor financial choices and inconsistent leadership, triggering flashpoints between administration, students and staff over the mission and cultural direction of the college.

Some have accused recent administrations of embezzlement, fraud and intimidation, resulting in multiple lawsuits. Students expressed frustration with a lack of resources and cultural competency among some school leaders. The college also has had trouble maintaining its accreditation.

Last year, a lawsuit crippled Bacone's finances. Ultimately, Michael made the decision to suspend classes for the spring semester. She hopes the deferment is temporary, but if the college can't muster up millions of dollars, Oklahoma’s oldest continually operating college likely will close its doors.

“It has endured for over 140 years through terrible decisions,” said Gerald Cournoyer, an instructor who was hired in 2019 to restart the college’s art program.

“Providing oversight for Bacone has been a struggle because of the leadership or lack thereof,” said Cournoyer, who also is a renowned Lakota artist. Some presidents focused time and money on athletic programs, others on Bacone's Baptist missionary roots. “When you put absolutely no money, nothing, not $20, not $10, into your fundraising efforts, this is what you get.”

During the time Patti Jo King was the director of the Center for American Indians at Bacone from 2012 to 2018, leadership wanted to build a state-of-the-art museum to replace the 80-year-old building housing many priceless pieces of Native art.

“We didn’t even have the money to keep it open seven days a week,” said King, now a retired Cherokee professor, writer and academic.

Even when she first arrived on campus, King said Bacone's financial debts already had caught up to it. The student dorms didn’t have hot water, staff were severely underpaid and graduation rates among the college’s remaining students were low.

Still, she and other faculty endeavored to make it a place where Native students could find community, but Bacone’s old problems never went away. Like Cournoyer, after years of working toward rebuilding, she left in frustration.

Today, the old museum is empty. Its artifacts were moved to another location so they wouldn’t be exposed to extreme temperatures.

The remaining staff act as caretakers of the historic stone buildings that predate Oklahoma, themselves important pieces of the past. In the museum, Ataloa Lodge, the fireplace is made of stones sent to the college from Indigenous communities across the country: one from the birthplace of Sequoyah, one from the grave of Sitting Bull, another from the field where Custer died. Five hundred in all, each stone a memory.

Michael, the interim president, and others have been cleaning up buildings in hopes they might soon host graduation banquets and student gatherings. Other staff chase off looters. Rare paintings still hang across campus, including pieces by members of the Kiowa Six, who became internationally famous a century ago, and Johnnie Diacon, a Muscogee painter and alumnus whose work can be seen in the background of several episodes of the television show Reservation Dogs.

A few years ago, experts from a museum in Tulsa warned that many of the paintings are contaminated with mold, which will spread to other nearby works of art. Leslie Hannah, a Cherokee educator who sits on the college’s board of trustees, said he’s concerned, but the cost of restoring them falls far down the list, behind broken gas lines, flooded basements and a mountain of debt.

Bacone’s current financial crisis stems partially from a lawsuit brought by Midgley-Huber Energy Concepts, a Utah-based heating and air company that sued the college over more than $1 million in unpaid construction and service fees. Twice last year, the Muskogee County Sheriff’s Office put Bacone’s property up for sale to settle the debt. Both times the auction was called off, most recently in December.

MHEC owner Chris Oberle told KOSU last month that he intended to purchase the historic property. Attorneys for MHEC have not returned repeated requests for comment from The Associated Press.

Alumni have called the validity of any sale of the property into question, pointing to the

treaty right that established the campus and its listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Attorneys for the college declined to comment, citing the ongoing litigation.

Michael said she doesn’t know what stalled the auction, but she is grateful for more time to try to save Bacone.

Native American Tribe Sues to Get Remains of 2 Who Died at Boarding School

When two Native American boys from Nebraska died after being taken to a notorious boarding school hundreds of miles away in Pennsylvania, they were buried there without notice. Nearly 130 years later, the tribe wants the boys' remains back home.

So far, the Army has refused to return to the Winnebago Tribe the remains of Samuel Gilbert and Edward Hensley. A federal lawsuit filed on behalf of the tribe accuses the Army of ignoring a law passed more than three decades ago aimed at expediting the return of the deceased to Native American lands.

Samuel had been at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania for just 47 days when he died in 1895. Edward spent four years at the school before dying in 1899. Both died in their teens, but records do not disclose their exact ages. Tribal leaders weren't informed when the boys died, and relatives never learned what killed them.

The tribe made a formal request to the Office of Army Cemeteries for the remains in October but learned in December that the request was denied, according to the lawsuit filed January 17.

"The Army always sought to maintain a position of control, dominance over native peoples while they were alive — and while they were dead," said Greg Werkheiser of Cultural Heritage Partners, one of the lawyers for the tribe.

The bodies remain in a graveyard along with those of about 180 other children not far from where the school once stood in Carlisle, 1,850 kilometers from the tribe's eastern Nebraska home. The graveyard serves as a "tourist attraction," the lawsuit states.

A spokesperson for the Office of Army Cemeteries said she can't comment on pending litigation. But the spokesperson said in an email that Samuel and Edward, along with other children who died at the boarding school, are buried in individual graves with named headstones.

"The cemetery is a dignified resting place demonstrating respect and care of all the deceased buried there and is absolutely not treated as a tourist attraction," the spokesperson said.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School in south-central Pennsylvania, the first government-operated school for Native Americans, was founded by a former military officer, Richard Henry Pratt. He believed that Native Americans could be a productive part of society, but only through assimilation.

After it opened in 1879 in an old Army barracks, thousands of Native American children were sent by train and stagecoach to Carlisle. Drastic steps were taken to separate them from their culture, including cutting their braids, dressing them in military-style uniforms and punishing them for speaking their native languages. They were forced to adopt European names.

More than 10,000 children from more than 140 tribes passed through the school by the time it closed in 1918, including Olympian Jim Thorpe. The children — often taken against the will of their parents — endured harsh conditions that sometimes led to death from tuberculosis and other diseases. The remains of some of those who died were returned to their tribes. The rest are buried in Carlisle.

After the school closed, the property was transferred from the Department of Interior to the War Department. It was used by the Army for a rehabilitation hospital and the Medical Field Service School.

The OAC spokesperson said the original cemetery was "in an inappropriate location adjacent to the pre-existing refuse dump, and blacksmith shop," so the remains were moved in 1927 to another location on Carlisle Barracks. Servicemembers, veterans and their families also are buried there.

In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA. It allowed for remains to be returned to tribes at their request. But the lawsuit said the Army refused to follow that law and is instead requiring the tribe to adhere to an Army policy.

The difference: While NAGPRA requires the remains to be returned, Army policy gives the agency discretion to decide if, and when, to do so. It also requires a request from the boys' "closest living relative" — which the lawsuit called "nearly impossible to apply in these circumstances."

"Defendants' conduct perpetuates an evil that the United States Congress sought to correct when it enacted NAGPRA in 1990," the lawsuit states.

The Army has disinterred 32 remains of Native American children at the Army's expense since 2017, the OAC spokesperson said.

But Werkheiser said those remains weren't technically returned to the tribes, but rather to the children's relatives, and often after arduous waits. He said that using the Army process rather than NAGPRA "strips the tribes of all of their political rights."

Tribes whose members had remains returned include the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, Spirit Lake, Washoe, Umpqua, Ute, Rosebud Sioux, Northern Arapaho, Blackfeet, Oglala Sioux, Oneida, Omaha, Modoc, Iowa and Alaskan native.

"The Winnebago, after listening to what all those other tribes went through, said, 'We're not going to play this game. We're not going to be bullied.'"

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American Cabinet secretary, has pushed the government to reckon with its role in Native American boarding schools. In 2022, her agency released a report naming the 408 schools the federal government supported to strip Native Americans of their cultures and identities. At least 500 children died at some of the schools, including Carlisle.

The lawsuit states that the Winnebago Tribe "continues to experience the pain of knowing that Samuel's and Edward's spirits remain lost."

"The way Winnebago views it is that the boys have been waiting to come home for nearly 125 years," said another attorney involved in the lawsuit, Beth Wright of the Native American Rights Fund. "Their spirits can't rest, and they can't go on unless they are returned to the place that they were taken from."

South Dakota Tribe Bans Governor from Reservation Over US-Mexico Border Remarks

A South Dakota tribe has banned Republican Gov. Kristi Noem from the Pine Ridge Reservation after she spoke this week about wanting to send razor wire and security personnel to Texas to help deter immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border and also said cartels are infiltrating the state's reservations.

"Due to the safety of the Oyate, effective immediately, you are hereby banished from the homelands of the Oglala Sioux Tribe!" Tribe President Frank Star Comes Out said in a Friday statement addressed to Noem. "Oyate" is a word for people or nation.

Star Comes Out accused Noem of trying to use the border issue to help get former U.S. President Donald Trump re-elected and boost her chances of becoming his running mate.

Many of those arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border are Indigenous people from places like El Salvador, Guatemala and Mexico who come "in search of jobs and a better life," the tribal leader added.

"They don't need to be put in cages, separated from their children like during the Trump Administration, or be cut up by razor wire furnished by, of all places, South Dakota," he said.

Star Comes Out also addressed Noem's remarks in the speech to lawmakers Wednesday in which she said a gang calling itself the Ghost Dancers is murdering people on the Pine Ridge Reservation and is affiliated with border-crossing cartels that use South Dakota reservations to spread drugs throughout the Midwest.

Star Comes Out said he took deep offense at her reference, saying the Ghost Dance is one of the Oglala Sioux's "most sacred ceremonies," "was used with blatant disrespect and is insulting to our Oyate."

He added that the tribe is a sovereign nation and does not belong to the state of South Dakota.

Noem responded Saturday in a statement, saying, "It is unfortunate that President (Star) Comes Out chose to bring politics into a discussion regarding the effects of our federal government's failure to enforce federal laws at the southern border and on tribal lands. My focus continues to be on working together to solve those problems."

"As I told bipartisan Native American legislators earlier this week, 'I am not the one with a stiff arm, here. You can't build relationships if you don't spend time together,'" she added. "I stand ready to work with any of our state's Native American tribes to build such a relationship."

In November, Star Comes Out declared a state of emergency on the Pine Ridge Reservation due to increasing crime. A judge ruled last year that the federal government has a treaty duty to support law enforcement on the reservation, but he declined to rule on the funding level the tribe sought.

Noem has deployed National Guard troops to the Mexican border three times, as have some other Republican governors.

In 2021 she drew criticism for accepting a $1 million donation from a Republican donor to help cover the cost of a two-month deployment of 48 troops there.

Native American News Roundup January 28-February 3, 2024

Kiowa literary giant N. Scott Momaday walks on

Native Americans and the literary world are mourning the passing of celebrated Kiowa author and academician N. Scott Momaday. He was 89.

Born in 1934 in Lawton, Oklahoma, he was given the Kiowa name Tsoai-talee, or “rock-tree-boy,” a reference to Devil’s Tower, the tall rock formation in Wyoming that features in Kiowa cosmology. Hear him explain the name in the video below:

During his childhood, his family moved between various locations on the Navajo reservation and the Pueblo of Jemez in New Mexico.

Momaday graduated from the University of New Mexico in 1958 and briefly attended Virginia Law School. He taught for a year on the Jicarilla Apache reservation before being awarded a creative writing fellowship at Stanford University. He taught at the University of California-Santa Barbara and the University of California-Berkeley before becoming a professor of English and literature at the University of Arizona in 1982.

He authored many collections of fiction, poetry, and essays. His first novel, "House Made of Dawn," won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

Read more:

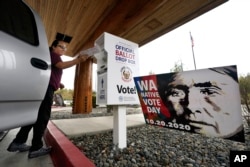

Native youth vote could be critical in the battleground state of Arizona

U.S. National Public Radio took a look this week at the voting power of young Native Americans in the state of Arizona.

In the 2020 election, they helped President Joe Biden win by more than 11,400 votes. In 2024, they could make a difference not just in the presidential election but in determining which party controls Congress.

"Native voters are powerful, and we can't be ignored anymore," said Jaynie Parris, a citizen of the Navajo Nation and executive director of Arizona Native Vote. “And we just need other people to meet us where we are and get on board."

NPR interviewed six Arizona voters who identify as Native American. They said neither political party has taken the time to get to know tribes and the problems that tribal communities must contend with, including water and environmental issues, the fentanyl crisis, and the lack of economic opportunities.

The report gave 25-year-old Alec Ferreira, a youth program coordinator for the San Carlos Apache Tribe, the final word: “Remember who is running the table right now. It's our time. Native people, we decided the last election. We can very well decide the next one.”

Read more:

California tribes call for changes to missing person alert system

California lawmakers last week held a hearing with California tribal leaders to discuss the successes and failures of the so-called “Feather Alert” system instituted in 2023.

Here’s how it works: when an Indigenous person goes missing, tribal law enforcement notifies local law enforcement, which in turn notifies California Highway Patrol (CHP), requesting that an alert go out on highway signs, cable networks and social media.

It is up to CHP, however, to decide whether an alert is warranted: local law enforcement must believe that the person is in danger and has gone missing under unexplainable or suspicious circumstances.

Native leaders complained that CHP turned down requests for Feather Alerts in at least three cases. They also called on lawmakers to amend the law to allow tribes to submit requests directly to CHP to speed up the process.

Read more:

Michigan Ojibwe galvanize to purchase sacred scrolls at auction

Members of the Keweenaw Bay Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe (KBIC) will shortly travel from Michigan to New York to retrieve a set of AnisshinaabeAnishinaabe (Ojibwe) birch bark scrolls known as wiigwaasabakoon that they purchased at an online auction.

Historically, Anishinaabe healers and spiritual leaders developed a form of pictographic writing that they inscribed onto birch bark to record histories, sacred teachings, songs and even medicinal formulas.

Because these scrolls came from a private collection, they were not subject to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which requires federally funded organizations to repatriate human remains and items of cultural or ceremonial importance.

With only days to go before the auction, KBIC tribe member Jerry Jondreau organized a fundraiser that enabled the tribe to purchase the scrolls.

“It was five days of anxiety and stress and lack of sleep and phone calls and emails and Zoom meetings and messages and trying to understand the whole process,” he told VOA. “There were more than 150 listings before the scrolls, so we had to stay glued to the auction site.”

The Anishinaabe are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes region of the U.S. and Canada.

Once the KBIC has authenticated the scrolls, they hope to loan them out to other Anishinaabe communities so those stories can be shared.

Native American News Roundup Jan. 21-27, 2024

Tribes sue administration over mega wind energy project

Two Native American tribes are suing the U.S. Interior Department and the Bureau of Land Management to halt construction of a $10 billion wind energy transmission line from New Mexico to California.

In their complaint, the Tohono O’odham Nation and the San Carlos Apache Tribe say the government failed to consult with them over the SunZia Southwest Transmission Project, which would run through properties of historic and cultural significance to several tribes.

“For more than a decade, the San Carlos Apache Tribe and others have been raising alarms about the need to protect the cultural resources in the San Pedro Valley from the impacts of the SunZia project,” Chairman Terry Rambler said in a news release on Wednesday.

With support from the nonprofit groups Archaeology Southwest and the Center for Biological Diversity, the tribes are calling for construction to stop until the Bureau of Land Management completes a “legally adequate inventory of historic properties and cultural resources that would be impacted by the project.”

Read more:

Nevada tribes call on feds to make massacre site a national monument

A coalition of three tribes in eastern Nevada wants the U.S. government to designate 100 square kilometers (40 square miles) as a national monument.

The Ely Shoshone, Duckwater Shoshone and the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation call the area Bahsahwahbee (Sacred Water Valley). Located in the bottom of Spring Valley near Great Basin National Park, it is the site of three massacres between 1850 and 1900 in which hundreds of their ancestors were killed by the U.S. Army and armed vigilantes.

“The people that were killed here were left here,” said Shoshone Delaine Spilsbury, who has lobbied for a Bahsahwahbee National Monument for decades. “Their spirits, their bodies, are in those trees. And so, we darn sure are going to protect those people.”

Nevada lawmakers and the state’s two U.S. senators, Catherine Cortez Masto and Jacky Rosen, support the proposal. Masto’s office says she will soon introduce a bill in Congress to designate the monument. If successful, the site would pass from the Bureau of Land Management to the National Park Service, which works with tribes to preserve their places and histories.

Read more:

Read more Shoshone history of the site here:

Harvard moves to ease burden on tribes seeking repatriation under NAGPRA

Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology says it will provide travel funds for tribal representatives to come to the museum for the physical repatriation of ancestors and associated funerary belongings. [[ https://peabody.harvard.edu/repatriation-visits ]]

“The funding will generally include transportation, hotel accommodations, and meals for direct round-trip travel and up to 3 nights in Cambridge [Massachusetts],” Peabody states on its website. It will also provide archival boxes and other containers but will not cover costs associated with ceremonies, special events or other services after items are repatriated.

“Some people have the mistaken impression that folks at Harvard are trying, by hook or by crook, to undermine this repatriation process. It’s not true,” said Joseph P. Gone, faculty director of the Harvard University Native American program. “No one at Harvard wants to hold on to these materials. Everyone wants to see these ancestors go back home where they belong.”

Read more:

Suicides up among Native youth in Montana

The CNN television news network this week focused on Native American suicide in the state of Montana, where youth suicide among the state’s 12 federally recognized tribes is more than five times the statewide rate for the same age group.

Native American youths are often exposed to more adverse childhood experiences, including poverty, substance abuse and family violence — part of a pattern of trauma rooted in historic policies of forced assimilation.

Suicide is preventable, but prevention programs available to Native American communities are chronically underfunded, and Indigenous experts say what few programs are available are not culturally relevant.

Read more:

Actress Lily Gladstone scores second ‘first’ in a month

January has been a very good month for Lily Gladstone, an actress who has Blackfeet and Nez Perce heritage. This week, she became the first Native American woman to be nominated for best actress at the Academy Awards for her role as Mollie Burkhart in Martin Scorsese’s epic “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

Earlier this month, she took home a Golden Globe award for the same performance.

“It’s time that Native characters based upon living, incredible women like Mollie Kyle be given the heart of these films,’ she told The New York Times. “‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ was an opportunity to restore a place onscreen for Native women that history has excluded us from.”

Read more:

Tribes, Environmental Groups Ask US Court to Block $10B Energy Project in Arizona

A federal judge is being asked to issue a stop-work order on a $10 billion transmission line being built through a remote southeastern Arizona valley to carry wind-generated electricity to customers as far away as California.

A 32-page lawsuit filed on January 17 in U.S. District Court in Tucson, Arizona, accuses the U.S. Interior Department and Bureau of Land Management of refusing for nearly 15 years to recognize "overwhelming evidence of the cultural significance" of the remote San Pedro Valley to Native American tribes, including the Tohono O'odham, Hopi, Zuni and San Carlos Apache Tribe.

The suit was filed shortly after Pattern Energy received approval to transmit electricity generated by its SunZia wind farm in central New Mexico through the San Pedro Valley east of Tucson and north of Interstate 10.

The lawsuit calls the valley "one of the most intact, prehistoric and historical ... landscapes in southern Arizona" and asks the court to issue restraining orders or permanent injunctions to halt construction.

"The San Pedro Valley will be irreparably harmed if construction proceeds," it says.

Government representatives declined to comment Tuesday on the pending litigation. They are expected to respond in court. The project has been touted as the biggest U.S. electricity infrastructure undertaking since the Hoover Dam.

Pattern Energy officials said Tuesday that the time has passed to reconsider the route, which was approved in 2015 following a review process.

"It is unfortunate and regrettable that after a lengthy consultation process, where certain parties did not participate repeatedly since 2009, this is the path chosen at this late stage," Pattern Energy spokesperson Matt Dallas said in an email.

Plaintiffs in the lawsuit are the Tohono O'odham Nation, the San Carlos Apache Tribe and the nonprofit organizations Center for Biological Diversity and Archaeology Southwest.

"The case for protecting this landscape is clear," Archaeology Southwest said in a statement that calls the San Pedro Arizona's last free-flowing river and the valley the embodiment of a "unique and timely story of social and ecological sustainability across more than 12,000 years of cultural and environmental change."

The valley represents an 80-kilometer (50-mile) stretch of the planned 885-kilometer (550-mile) conduit expected to carry electricity from new wind farms in central New Mexico to existing transmission lines in Arizona to serve populated areas as far away as California. The project has been called an important part of President Joe Biden's goal for a carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035.

Work started in September in New Mexico after negotiations that spanned years and resulted in approval from the Bureau of Land Management, the federal agency with authority over vast parts of the U.S. West.

The route in New Mexico was modified after the U.S. Defense Department raised concerns about the effects of high-voltage lines on radar systems and military training operations.

Work halted briefly in November amid pleas by tribes to review environmental approvals for the San Pedro Valley and resumed weeks later in what Tohono O'odham Chairman Verlon M. Jose characterized as "a punch to the gut."

SunZia expects the transmission line to begin commercial service in 2026, carrying more than 3,500 megawatts of wind power to 3 million people. Project officials say they conducted surveys and worked with tribes over the years to identify cultural resources in the area.

A photo included in the court filing shows an aerial view in November of ridgetop access roads and tower sites being built west of the San Pedro River near Redrock Canyon. Tribal officials and environmentalists say the region is otherwise relatively untouched.

The transmission line also is being challenged before the Arizona Court of Appeals. The court is being asked to consider whether state regulatory officials there properly considered the benefits and consequences of the project.

Native American News Roundup January 14-20, 2024

New NAGPRA rules aim to speed up compliance

Revisions to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) went into effect January 12.

NAGPRA directs federally funded museums and federal agencies to catalogue all Native American human remains, funerary items, and objects of cultural significance in their collections, to submit the information to a National Park Service database and to work with tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations to repatriate them.

They now have until January 2029 to update their inventories.

Previously, institutions have taken advantage of a loophole in the law allowing them to hold on to artifacts deemed “culturally unidentifiable.” That category has now been removed, and Native American traditional knowledge or geographical information will be sufficient for proving cultural affiliation going forward.

Institutions must now get permission from lineal descendants and/or Native American Tribes or Native Hawaiian Organizations (NHOs) before displaying, giving access to or allowing any research on remains or cultural artifacts.

"Pending consultation with the represented communities, we have covered all cases that we believe contain cultural items that could be subject to these regulations," Chicago’s Field Museum announced last week.

Harvard University’s Peabody Museum, which has the third-largest collection under NAGPRA, issued no statement but has closed several galleries for “maintenance” – including its Hall of the North American Indian -- until early February.

Tribe sues Army for failing to repatriate remains of boarding school students

The Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska this week filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Army asking that it repatriate the remains of two Winnebago children who died at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.

Carlisle records show that in September 1895, Samuel Gilbert and Edward Hensley were among a group of 11 youths taken from their families and sent to Carlisle. Both died of pneumonia – Samuel, just weeks after his arrival, and Edward in June 1899. They were both buried in the school cemetery, which is today an Army installation.

Last October, the Winnebago formally requested that the Army repatriate the remains in compliance with NAGPRA.

“Defendants denied Winnebago’s request on the erroneous basis that NAGPRA does not apply to the repatriation of ‘Native American human remains’ …in their possession and control at Carlisle Cemetery,” the complaint states.

A June 2014 memorandum from the Army’s Assistant Chief of Staff for Installation Management clearly states, “NAGPRA applies to all Army Commands, installations, and activities and places affirmative duties on the Army for the protection, inventory, and disposition of Native American cultural items.”

In this case, the Army, says its “disinterment and return” process requires the identification of a “closest living relative” for remains from Carlisle Cemetery to be disinterred, not tribal nations.

“Because the Carlisle students often died as children themselves or died without children, they have no direct descendants and the identification of a “closest living relative” is nearly impossible,” a statement from the Native American Rights Fund says.

Read more:

New York tribes called to review ‘offensive’ artwork in state capitol

New York Governor Kathy Hochul is inviting New York tribes to review artwork in the State Capitol Building in Albany, citing “offensive imagery and distasteful representations of populations.”

“All New Yorkers should feel welcome and respected when visiting the State Capitol,” she said in her 2024 State of the State report. “Indigenous peoples, in particular, are often depicted in artworks in a manner that reflects harmful racial stereotypes and glorifies violence against Indigenous peoples.”

The ceiling of the governor’s reception room features 25 paintings by 20th Century muralist William deLeftwich Dodge. Unveiled in 1931, they depict the military history of New York, including a scene showing French explorer Samuel Champlain “killing first Indian.”

Read more:

Treasure hunter wreaks havoc at historic Pueblo site

A Utah treasure hunter has been charged with a second-degree felony for tunneling more than four meters into a 1,000-year-old archaeological site.

Acting on a tip from a concerned citizen, authorities in Washington County, Utah, say they found Eduardo Humberto Seoane, 51, digging at the ancient Pueblo Indian site that includes 100 petroglyphs that archaeologists believe are at least 500 years old.

“We couldn’t believe what we were seeing,” said Washington County Sheriff’s Office Sgt. Darrell Cashin. “The suspect had power and hand tools out there, and he’d been excavating for quite some time.”

Authorities say Seoane told them he was prospecting for precious minerals, but they discovered that he belongs to several treasure-hunter groups.

"It's almost impossible to calculate the damage caused by this guy," said a press release from Trust Lands Administration lead archaeologist Joel Boomgarden. "It is important for people to remember that the archaeological record of Utah is a finite resource. Nobody is making 1,000-year-old ancestral Puebloan sites anymore. Once they are gone, there is no going back."

Read more:

Canada Signs Over Control of Arctic Lands to Inuit Territory

Canada's Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on Thursday signed over control of resource-rich Arctic lands to the government of the predominantly Inuit territory of Nunavut, in what was billed as the largest land transfer in Canada's history.

Nunavut, at more than 2 million square kilometers (800,000 square miles), is almost three times the size of the U.S. state of Texas and is believed to hold some of the richest resource deposits in the country, including gold, diamonds and rare earth minerals, as well as oil and gas.

With global warming, the Arctic territory is becoming more accessible for mining and shipping.

In its capital, Iqaluit, Trudeau signed a devolution agreement with Nunavut Premier P.J. Akeeagok.

It effectively gives the territorial government of Nunavut responsibility over its lands and resources and the right to collect royalties that would otherwise go to the federal government.

"Inuit have hunted and fished and lived on these lands for generations, some going back well before recorded history. Today begins a new chapter in the history of Nunavut, a transformative chapter," Trudeau said at the signing ceremony.

"This is a place that is rich with culture, traditional knowledge, critical minerals and other resources that are needed as we build the economy of the future together," he said.

"And with this increased control, [the government and people of Nunavut] will be able to have more say and more prosperity."

The agreement comes after decades of negotiations between Nunavut and the federal government. It is to be fully implemented over the next three years.

"It's our land, our resources, [now] in the hands of our people," cheered Akeeagok.

Ottawa started in the 1960s gradually transferring responsibilities for health, education, social services and other areas to its Arctic territories.

Nunavut, which was created in 1999, is the last of Canada's three Arctic territories — after the Northwest Territories and the Yukon — to take full control of its lands.

Native American News Roundup Jan. 7-13, 2024

Mission to deposit human remains on moon a 'desecration'

The United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket launched Monday from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida carrying Astrobotic Technology’s lunar lander Peregrine, which contains human remains and DNA to be deposited on the moon.

Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren called this a “profound desecration.”

“The moon is sacred,” Nygren posted to Facebook. “It’s in our songs, our stories, our creation. The moon is a place that we’ve looked to for hundreds of years to make sure that we continue to exist. It’s part of ceremonies that have been around for the Navajo people for a long, long time.”

On Friday, Astrobotic reported that Peregrine's fuel leak had slowed down; the craft was about 225,000 miles from Earth and had about 48 hours of propellant remaining.

Read more:

Two North Dakota tribes win voting rights lawsuit

A federal judge in North Dakota this week ordered state officials to create a new joint legislative district for two federally recognized tribes.

The Spirit Lake Nation and the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa sued North Dakota in 2022 arguing that a map created through redistricting in 2021 that placed them in separate districts eroded their voting power in violation of the Voting Rights Act.

U.S. District Judge Peter Welte's ruling comes after North Dakota lawmakers failed to meet a December deadline to come up with an alternative map. Tribal attorneys say the current map lowered tribes’ chances to elect candidates of their choice and receive a fair share of public resources.

Read more:

South Dakota to tribe: pay for records upfront or waive your sovereign immunity

In a related story, the city of Martin, South Dakota, is calling on the Oglala Lakota Nation to either waive its sovereign immunity or pay what could end up being a substantial amount of money in attorney and administrative fees to receive public records related to the city’s new redistricting map.

In August 2023, the tribe requested city records relating to potential violations of the Voting Rights Act over the past two decades, including election results, redistricting maps, agendas from meetings where redistricting was discussed and all analyses of the Voting Rights Act.

Attorneys for the city responded that the cost to pull 20 years of records could reach $500 an hour and asked either for payment up front or for the tribe to waive its sovereign immunity, allowing the city to file a lawsuit if the tribe fails to pay.

The city defends the action, saying it is small and lacks resources. The tribe now says it will ask for only 10 years of records and has appealed to the state for help.

Read more:

Hawaii’s ‘last princess’ Abigail Kawānanakoa left $100M to Native Hawaiians

Multimillionaire Abigail Kinoiki Kekaulike Kawānanakoa, considered by Native Hawaiians as the last Hawaiian princess and one of state’s largest landowners, died more than a year ago. This week, details of her estate were settled and made public.

She left $40 million to her wife and tens of millions to other individuals, including former housekeepers and longtime employees. The remainder of her estate, at least $100 million, will go to Native Hawaiian causes.

Kawānanakoa was the great-granddaughter of Irish industrialist James Campbell, who arrived in the then-Kingdom of Hawaii in 1850 and married Native Hawaiian aristocrat Abigail Kuaihelani Maipinepine Bright. Campbell made his fortune in Hawaii’s sugar cane industry, real estate and ranching.

Read more:

Lily Gladstone wins big at Golden Globes

Lily Gladstone made history at the Golden Globe Awards on Sunday when she was named best actress in a motion picture drama for her performance in Martin Scorsese’s epic film “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

Gladstone, 37, grew up on the Blackfeet Reservation in northwestern Montana and opened her acceptance speech in the traditional Blackfeet manner: "Hello my friends/relatives. My name is Piitaaki [Eagle Woman]. I am Blackfeet. I love you all,” she said in Siksika, the Blackfeet language.

"And this is for every little rez kid, every little urban kid, every little Native kid out there who has a dream, who is seeing themselves represented in our stories, told by ourselves, in our own words, with tremendous allies and tremendous trust," Gladstone added.

The Golden Globe Awards are held each January, honoring artists and professionals for their work in the television and film industry.

Read more:

Enduring Relationship With Horses Aids Popularity of Rodeo in Indian Country

Kicking up a cloud of dust, the men riding bareback were in a rowdy scramble to be the first to lean down from atop their horses and grab hold of the chicken that was buried up to its neck in the ground.

The competition is rarely on display these days and most definitely not with a live chicken. And yet, it was this Navajo tradition and other horse-based contests in tribal communities that evolved into a modern-day sport that now fills arenas far and wide: rodeo.

With each competition, Native Americans have made them decidedly theirs — a shift from the Wild West shows and Fourth of July celebrations of centuries past that reinforced stereotypes. Rodeo has provided a stage for Native Americans, many of whom had nomadic lifestyles before the U.S. established reservations, to hone their skills and deepen their relationship with horses.

“It was really a way to bring something good out of a really tough situation and become successful economically and, of course, have some joy and celebration in the rodeo world,” said Jessica White Plume, who is Oglala Lakota and oversees a horse culture program for the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation in North Dakota.

The sport was born in the mastering of skills that came as horses transformed hunting, travel and welfare. Grandstands often play host to mini family reunions while Native cowboys and cowgirls show off their skills roping, riding and wrestling livestock.

One of those rising stars is Najiah Knight, a 17-year-old who is Paiute from the Klamath Tribes and trying to become the first female bull rider to compete on the Professional Bull Riders tour. Her upbringing in a small town, riding livestock is a familiar tale across Indian Country.

Growing up, Ed Holyan’s grandma would drop off him and his brother in Coyote Canyon — an isolated and rugged spot on the Navajo Nation — to tend sheep. When they got bored, they'd rope rocks, the Shetland pony and calves with small horns, he said.

“We’d seen my dad rodeo and my older brother rodeoed, so we knew we had the foundation,” said Holyan, the rodeo coach at Diné College in Tsaile, Arizona. “It was in our blood.”

For Kennard Real Bird, who rode saddle broncs for 16 years, horses provided freedom on the Crow reservation in Montana. The river where the Battle of Little Bighorn took place coursed through the land, prairie extended into pine trees and high buttes beckoned with even wider-ranging views.

The ranching life developed into a career as a stock contractor and a reluctant rodeo announcer who deals in observational comedy, including at the Sheridan, Wyoming, rodeo.

No event there is as big of a crowd pleaser than the Indian Relay Races held in July — a contest rooted in buffalo hunts on the Great Plains or raids of camps, depending on who you ask.

A team consists of someone to catch the incoming horse, two people to hold horses and a rider who speeds around the track bareback, twice switching to another horse.

“It's the most fun you can have with your moccasins on,” Real Bird, 73, jokingly tells crowds.

Kidding aside, horsemanship is a celebrated part of tribes' history.

On the Crow and Fort Berthold reservations, tribal members compete for the title of ultimate warrior by running, canoeing and bareback horse racing. Back on the Navajo Nation in the Four Corners region, rodeo is still called “ahoohai,” derived from the Navajo word for “chicken.”

The Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College on the Fort Berthold reservation offers Great Plains horsemanship as a tract in its two-year equine studies program, the only such program at a tribal college or university.

Instructors highlight history like keeping prized horses in an earth lodge and the North Dakota Six Pack, a group of bronc and bull riders that included MHA Nation citizen Joe Chase, who shined on the rodeo circuit in the 1950s, said Lori Nelson, the college's director of Agriculture and Land Grants.

The tribe recently purchased kid-safe mini bulls and has bucking horses to revive rodeo among the youth, said Jim Baker, who manages the tribe's Healing Horse Ranch.

“That’s one of our goals to keep the horse culture alive among our people,” he said.

The largest stage for all-Native rodeo competitors is the Indian National Finals Rodeo held in Las Vegas. Tribal regalia, blessings bestowed by elders and flag songs that serve as tribes’ national anthems are as much staples as big buckles and cowboy hats.

Tydon Tsosie, of Crownpoint, New Mexico, restored the town’s moniker to “Navajo Nation Steer Wrestling Capital” when he won the open event there this year as a 17-year-old. In his family, rodeo runs through generations with songs, prayers and respect for horses.

Tsosie plans to continue the tradition, proudly proclaiming, “I see myself doing it for the rest of my life until I get old."

Nevada Tribe Says Coalitions, Not Lawsuits, Will Protect Sacred Sites as US Advances Energy Agenda

The room was packed with Native American leaders from across the United States, all invited to Washington to hear from federal officials about President Joe Biden's accomplishments and new policy directives aimed at improving relationships and protecting sacred sites.

Arlan Melendez was not among them.

The longtime chairman of the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony convened his own meeting 4,023 kilometers away. He wanted to show his community would find another way to fight the U.S. government's approval of a massive lithium mine at the site where more than two dozen of their Paiute and Shoshone ancestors were massacred in 1865.

Opposed by government lawyers at every legal turn, Melendez said another arduous appeal would not save sacred sites from being desecrated.

"We're not giving up the fight, but we are changing our strategy," Melendez said.

That shift for the Nevada tribe comes as Biden and other top federal officials double down on their vows to do a better job of working with Native American leaders on everything from making federal funding more accessible to incorporating tribal voices into land preservation efforts and resource management planning.

The administration also has touted more spending on infrastructure and health care across Indian Country.

Many tribes have benefited, including those who led campaigns to establish new national monuments in Utah and Arizona. In New Mexico, pueblos have succeeded in getting the Interior Department to ban new oil and natural gas development on hundreds of square miles of federal land for 20 years to protect culturally significant areas.

But the colony in Reno and others like the Tohono O'odham Nation in Arizona say promises of more cooperation ring hollow when it comes to high-stakes battles over multibillion-dollar "green energy" projects. Some tribal leaders have said consultation resulted in little more than listening sessions, with federal officials not incorporating tribal comments into the decision making.

Rather than pursue its claims in court that the federal government failed to engage in meaningful consultation regarding the lithium mine at Thacker Pass, the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony will focus on organizing a broad coalition to build public support for sacred places.

Tribal members are concerned other culturally significant areas will end up in the path of a modern-day Gold Rush that has companies scouting for lithium and other materials needed to meet Biden's clean energy agenda.

Melendez was among those thrilled when Biden appointed Deb Haaland to lead the Interior Department. A member of Laguna Pueblo, Haaland is the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary.

Melendez, a former member of the U.S. Human Rights Commission who has led his colony for 32 years, said he understands the difficulty of navigating the electoral landscape in a western swing state where the mining industry's political clout is second only to the power wielded by casinos.

Still, he was disappointed Haaland declined an invitation to visit the massacre site.

"The largest lithium project in the United States and they don't even have the time to come out here and meet with the tribal nations in the state of Nevada," he said.

The tribe's lawyer, Will Falk, urged other tribes to resist "tricking ourselves into believing that just because the first Native American secretary of Interior is in office that she actually cares about protecting sacred sites."

Interior Department spokeswoman Melissa Schwartz didn't respond directly to that criticism but said in an email to The Associated Press that there has been "significant communications and partnership with tribes in Nevada."

The federal government in early December published new guidance for dealing with sacred sites. While Falk and others are skeptical, they acknowledged the document speaks to concerns tribes have raised for decades.

Among other things, the guidance says federal agencies should involve tribes as early as possible when planning projects to identify potential impacts to sacred sites and to determine whether mitigation measures can allay concerns. Agencies also should consult with tribes that attach significance to the project area, regardless of where they are located.

It also suggests Indigenous knowledge should be on equal footing with other sciences and incorporated into the federal decision-making process. That knowledge can consist of practices, cultural beliefs and oral and written histories that tribes have developed over many generations.

Justin C. Ahasteen, executive director of the Navajo Nation Washington (D.C.) Office, said the new guidance appears to have incorporated some of the recommendations made by tribal leaders but that it could have gone further.

"If this guidebook increases transparency in the consultation process, we will take it as a win," Ahasteen said. "But ultimately the thing we all seek is for the federal government to acknowledge the necessity of tribal consent before changing rules that affect tribes."

The problem, Falk said, is none of it is legally binding.

"These kinds of documents function more as pacifying propaganda," he said.

Western Shoshone Defense Project Director Fermina Stevens said the changes were "more 'lip service' for the government to deal with the 'Indian problem' in this new day and age of mineral extraction."

Morgan Rodman, executive director of the White House Council on Native American Affairs, disagrees. He said the guidance is intended to serve as a springboard to improve engagement with tribes and that the administration will be aggressive with training to make sure employees have an understanding of what sacred sites are.

"While change certainly doesn't happen overnight, it's part of a continuum of important policy statements — part of the momentum we've been building the last three years," he said in an interview.

Rodman made clear he wasn't referencing Thacker Pass, but some directives he highlighted have been key points of contention in that case.

U.S. Judge Miranda Du in Reno twice ruled the tribe failed to prove the massacre occurred on the specific grounds of the mining project, or that far-flung tribes had a legal stake in the fight. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld her earlier ruling in July.

The tribe says the government has ignored evidence that the land they consider sacred isn't limited to a specific site where the U.S. Calvary first attacked men, women and children as they slept.

They cited newspaper accounts, diaries and a government surveyor's report documenting human skulls discovered along a miles-long escape route crossing the mine site where troops killed and scalped those who tried to flee.

Tribal historic preservation officer Michon Eben said the whole stretch is an unmarked burial ground.

Melendez said he's pleased Biden has promised to enhance consultation.

But if federal agencies don't follow through, he said, "Well, it's just words that really don't mean anything to us."

Native American News: 2023 in Review

These are some of the Native American-related news stories that made headlines in 2023:

Biden commits to reforms

The White House hosted a third Tribal Nations Summit in December, detailing initiatives and investments in Indian Country over the past three years.

President Joe Biden has nominated or appointed a record number of Native Americans to positions in the federal government. Most recently, the U.S. Senate confirmed his nomination of the first Native American to serve on a federal court, former Cherokee Nation Attorney General Sara Hill.

The Interior Department this year continued its investigation into the federal Indian boarding school system and launched an oral history project to document survivor experiences.

The administration announced 190 new agreements, including deals allowing tribes to comanage federal lands and waters, funding for fish and wildlife restoration and help in mitigating the impact of climate change on tribal land.

Biden issued a new executive order reiterating the administration’s commitment to strengthen the government-to-government relationship with tribes, to give tribes more say in their affairs, and to make it easier for tribes to access funding.

Like others issued in recent years, the order stipulates that it is “not intended to, and does not, create any right, benefit, or trust responsibility, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law or in equity by any party against the United States, its departments, agencies, or entities, its officers, employees, or agents, or any other person.”

Read the administration’s 81-page 2023 progress report to tribal nations here:

SCOTUS upholds ICWA, gives preference to Native adoptive, foster families

Native Americans this year celebrated a major victory in the U.S. Supreme Court after Justices in June affirmed the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) by a vote of 7 - 2. ICWA is a federal law that sets standards for the removal of Native American children from their homes and directs state welfare agencies to give preference to Native American families when placing Native children in foster or adoptive homes.

Challengers to ICWA say the law is racially discriminatory and deprives states of their rights to manage welfare cases.

Read what this means for tribes here:

Pope Francis officially rejects ‘doctrine of discovery’

The Vatican this year formally repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery, a legal and ideological concept rooted in a series of mid-15th century papal bulls (edicts) giving a blessing for the European conquest of “the New World.”

“Historical research clearly demonstrates that the papal documents in question, written in a specific historical period and linked to political questions, have never been considered expressions of the Catholic faith,” the March 30 statement read. “The church is also aware that… these documents were manipulated for political purposes by competing colonial powers in order to justify immoral acts against Indigenous peoples that were carried out, at times, without opposition from ecclesiastical authorities.”

Institutions pressured to return Native American remains and artifacts

The Interior Department in December issued new rules to spur institutions into complying with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

Passed in 1990, NAGPRA directs all federally funded institutions and federal agencies to catalogue all Native American human remains, funerary items, and objects of cultural significance in their collections; submit the information to a National Park Service database; and work with tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations to repatriate them.

The new rules eliminate a loophole that allowed institutions to hold onto remains they deem “culturally unidentifiable” and extends the deadline for federally funded institutions to complete catalogs of their holdings.

Killers of the Flower Moon: A boost for Native American representation in film

The long-anticipated Martin Scorsese film "Killers of the Flower Moon” opened in October. Based on the 2017 book by David Grann, it explores the “Reign of Terror,” a dark period in 1920’s Oklahoma when a white cattle rancher orchestrated the murders of an untold number of Osage tribe members to get their oil headrights.

Most Native viewers have praised Scorsese for shedding light on acts of genocide against the Osage Nation, for consulting with Osage tribe members and for casting dozens of Osage and other Indigenous Americans as actors and consultants—most notably, Nez Perce/Blackfeet actor Lily Gladstone in a leading role.

Others complained that the story was not told from the perspective of the Osage people but from the view of the white men conspiring to kill them.

Read more:

Record allegations of Indigenous identity theft

They are called “Pretendians,” “Indigenots” or “Wannabindians” — individuals who fabricate Indigenous identity to get ahead in academia, the arts and even government.

This year, Indigenous groups in the U.S. and Canada accused a record number of alleged fake Indians, including a Hollywood producer, university professors, politicians and a horror fiction writer.

But one accusation sent shockwaves around the world. In October, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reported that singer/songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie was not Cree from the Piapot First Nation in Saskatchewan but a New Englander of mixed English and Italian ancestry.

Sainte-Marie has strongly denied the report but has removed all references to Indigeneity on her website and declined calls to take a DNA test.

Climate Change Brings Collapsing Stilts and Hungry Bears to Little Diomede Island

Last month, Native Alaskans on Little Diomede Island awoke to see their city office collapsing into the community school next door.

For the Ingalikmiut people [Inupiat] in the Bering Strait, halfway between Siberia and the Alaska mainland, this was the latest crushing evidence of the impact of climate change in the Arctic.

“Looking at the timber and the wood timbers [stilts] that had supported the office building, we didn’t find them to be deteriorating,” explained Sean McKnight, who was part of an inspection team from the Nome-based tribal consortium Kawerak Inc. “Basically, the permafrost is degrading, so building foundations are sinking and sliding.”

Inspectors discovered that several other buildings have also begun to shift downhill.

“Our opinion is that this is going to affect every building in Diomede,” McKnight said.

So, how will Diomeders cope?

“These people have been living here for thousands of years,” McKnight told VOA. “They’re adaptive. They’re resourceful. When they have a problem, they just fix it. This is their home. They have no choice.”

Living on stilts

The city of Diomede, population about 86, consists of three dozen buildings on stilts on the lower slope of an almost vertical cliff. There is a washeteria, where residents shower and do laundry, a health clinic, a small store and a helipad.

In past winters, community members used bulldozers to carve a runway into the ice offshore. This allowed planes to deliver food and supplies. Today, the ice offshore is all new — that is, ice that has not been able to survive a summer melt season.

“The last time we had an ice runway for essential air service was 2014, and that was only for two weeks I believe,” says Diomede tribal coordinator Frances “Sistuq” Ozenna. “Today, we have chopper services year-round. They fly passengers on Mondays, and on Wednesdays, they do mail runs. But the weather always interferes."

And that can lead to critical shortages of food, medicine and supplies.

“You have to reserve as much as you can, just in case it takes a while for us to get any services to Diomede,” Ozenna told VOA.

That means the tribe must rely more on traditional methods of subsistence, harvesting wild greens, berries or potatoes in spring and seasonal hunting of migrating marine mammals, including walrus and seals.

If the ice is thick enough to cross, that is.

“Food security for Diomede, I think it's always going to be an issue, because we have limitations in transportation and hunting equipment,” Ozenna says. “You have to know how to survive Diomede. It can get pretty frustrating.”

Undercover predators

In recent years, climate change has introduced a new threat to Diomeders: polar bears, the largest land carnivores on Earth.

Unlike other bear species, polar bears do not hibernate in winter but travel far with the ice in search of seals. Normally at this time of year, they would be far out on the ice, away from human settlements.

But as their habitat melts, they can end up stranded on land.

“You never know when they’re going to come in,” Ozenna said. “They're most likely to come in at nighttime or during a blizzard, when things are obscured.”

School children are particularly vulnerable, which is why Diomede men will get up early, grab their rifles and patrol the streets, on the lookout for hungry bears.

Diomeder Brendon Ozenna captured this video of a polar bear and her cub attempting to access the community school on November 5, 2021.

After the buildings collapsed, Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy issued a disaster declaration for Diomede that makes state resources available to help rebuild the city office.

For now, the school’s 22 students have switched to distance learning until after the Christmas holidays.

This, it would seem, is a blessing in disguise — over the past two weeks alone, Ozenna says she has seen three polar bears lurking around town looking for their next meal.

More than 1,000 kilometers northeast of Diomede on Alaska's northern coast, VOA's Natasha Mozgovaya reports on permafrost and polar bears in the city of Kaktovik.

NM Extends Ban on Oil and Gas Leasing Around Area Sacred to Native Americans

New oil and natural gas leasing will be prohibited on state land surrounding Chaco Culture National Historical Park, an area sacred to Native Americans, for the next 20 years under an executive order by New Mexico Land Commissioner Stephanie Garcia Richard.

Wednesday's order extends a temporary moratorium that she put in place when she took office in 2019. It covers more than 293 square kilometers of state trust land in what is a sprawling checkerboard of private, state, federal and tribal holdings in northwestern New Mexico.

The U.S. government last year adopted its own 20-year moratorium on new oil, gas and mineral leasing around Chaco, following a push by pueblos and other Southwestern tribal nations that have cultural ties to the high desert region.

Garcia Richard said during a virtual meeting Thursday with Native American leaders and advocates that the goal is to stop the encroachment of development on Chaco and the tens of thousands of acres beyond the park's boundaries that have yet to be surveyed.

"The greater Chaco landscape is one of the most special places in the world, and it would be foolish not to do everything in our power to protect it," she said in a statement following the meeting.

Cordelia Hooee, the lieutenant governor of Zuni Pueblo, called it a historic day. She said tribal leaders throughout the region continue to pray for more permanent protections through congressional action.

"Chaco Canyon and the greater Chaco region play an important role in the history, religion and culture of the Zuni people and other pueblo people as well," she said. "Our shared cultural landscapes must be protected into perpetuity, for our survival as Indigenous people is tied to them."

The tribal significance of Chaco is evident in songs, prayers and oral histories, and pueblo leaders said some people still make pilgrimages to the area, which includes desert plains, rolling hills dotted with piñon and juniper and sandstone canyons carved by eons of wind and water erosion.

A World Heritage site, Chaco Culture National Historical Park is thought to be the center of what was once a hub of Indigenous civilization. Within park boundaries are the towering remains of stone structures built centuries ago by the region's first inhabitants, and ancient roads and related sites are scattered further out.

The executive order follows a tribal summit in Washington last week at which federal officials vowed to continue consultation efforts to ensure Native American leaders have more of a seat at the table when land management decisions affect culturally significant areas. New guidance for federal agencies also was recently published to help with the effort.

The New Mexico State Land Office is not required to have formal consultations with tribes, but agency officials said they have been working with tribal leaders over the last five years and hope to craft a formal policy that can be used by future administrations.

The pueblos recently completed an ethnographic study of the region for the U.S. Interior Department that they hope can be used for decision-making at the federal level.