Native Americans

Native American news roundup, March 31-April 6, 2024

Updated standards on race and ethnicity data will benefit Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders

The federal government’s Office of Management and Budget has revised standards for collecting and presenting race data to ensure the diversity of the U.S. population is adequately represented.

Among the most affected will be Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, who have previously been lumped into a single category. Now they will be allowed to identify as, for example, Fijian, Tahitian, Samoan or Chuukese.

Members of the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, or CAPAC, described the changes as a “historic milestone” for Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, or AANHPI, communities.

“As CAPAC has consistently emphasized, grouping our AANHPI communities together often masks the disparities that certain racial or ethnic groups face, including on economic prosperity, health outcomes, home ownership or educational attainment, and make government programs and services less responsive and effective,” said CAPAC chair, U.S. Representative Judy Chu, a Democrat from California.

Read the White House announcement here:

Governor, tribes, continue to clash in South Dakota

South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem released a statement Tuesday calling on tribes to “banish cartels from tribal lands.”

“The cartels instigate drug addiction, murder, rape, human trafficking and so much more in tribal communities across the nation, including in South Dakota,” Noem said.

She has repeatedly suggested that tribal leaders are misusing federal funds. She has also criticized President Joe Biden for failing to adequately fund tribal law enforcement.

During a special session in January, Noem told state lawmakers that South Dakota has been “directly affected” by an invasion of drug and human traffickers from the southern U.S. border and that cartels were working inside reservations in the state.

In a March town hall meeting, she alleged that tribal leaders were personally profiting from cartels.

Noem has also called for the government to conduct “public and comprehensive single audits” of all federal funds allocated to South Dakota’s nine Native American tribes.

The Single Audit Act requires an annual audit of all nonfederal entities, including tribes that spend over $750,000 in Federal Financial Assistance.

Indian Country Today reports that a search of the Federal Audit Clearinghouse shows that most South Dakota tribes regularly completed audits — at least up until 2020, when “an influx of funding for COVID-19 relief caused issues backlogging the process and overwhelming the treasurers.”

This week’s statement noted that following Noem’s call for an audit, “multiple members of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, including tribal councilmembers, unveiled serious allegations of corruption within tribal government.”

"Video of these comments will be made available upon request," it said.

At VOA’s request, Noem’s press secretary sent four video clips but failed to specify where they came from or how they were obtained.

VOA determined that they had been clipped from Oglala Lakota Sioux, or OST, tribal council meetings March 26-27 as seen on KOLC- TV's YouTube page, in which council members alleged the misuse of federal emergency funds by the tribe’s housing authority and questioned why the tribe was contracting to hire “Mexicans from Texas” when unemployment on the reservation stands at 80%, among other complaints.

Tribal leaders in South Dakota have expressed outrage over her remarks, accusing her of being racist and working to perpetuate stereotypes.

This week, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe banned her from their reservation, following in the footsteps of the OST, which banned her from Pine Ridge in February.

Handful of Native American tribes will experience total solar eclipse

On Monday, a total solar eclipse will cross the United States from Texas to New York. Anyone inside its 115-mile-wide path (185 kilometers) of totality will be able to see the moon fully block the face of the sun. Anyone outside of that path will see a partial eclipse.

A map of the eclipse’s path reveals that tribal nations in only four states will experience totality: the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe in Texas, the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma, some Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in New York and the Penobscot Nation in Maine.

The federal government recognizes 574 tribes, 347 of them in the lower 48 states.

No federally recognized tribes reside in the other states over which the eclipse will travel. Those states are Arkansas, Tennessee, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania — landscapes where prior contact and policies of forced removal eliminated hundreds of vibrant Indigenous communities.

Nor do any federally recognized tribes remain in Vermont, New Hampshire, Georgia, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, the District of Columbia or West Virginia.

"Rezbians" addresses same-sex love on reservations

VOA reporter Gustavo Martinez Contreras reported this week on an Indigenous graphic artist in New Mexico who is using a comic book to tell a story about same-sex love and identity on a Native American reservation.

Native American artist tells tale of love, identity

An Indigenous graphic artist in the Southwest U.S. state of New Mexico is using a comic book to tell a story about same-sex love and identity on a Native American reservation. Gustavo Martínez Contreras has our story from Albuquerque.

Uranium being mined near Grand Canyon as prices soar

The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that comes as global instability and growing demand drive uranium prices higher.

The Biden administration and dozens of other countries have pledged to triple the capacity of nuclear power worldwide in their battle against climate change, and policy changes are being adopted by some to lessen Russia's influence over the supply chain.

But as the U.S. pursues its nuclear power potential, environmentalists and Native American leaders remain fearful of the consequences for communities near mining and milling sites in the West and are demanding more regulatory oversight.

The new mining at Pinyon Plain Mine near the Grand Canyon is happening within the boundaries of the Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukv National Monument that was designated in August by President Joe Biden. The work was allowed to move forward since Energy Fuels Inc. had valid existing rights.

Low impact with zero risk to groundwater is how Energy Fuels spokesperson Curtis Moore describes the project.

The mine will cover 6.8 hectares (16.8 acres) and operate for just a few years, producing about 907,000 kilograms (about 2 million pounds) of uranium — enough to power the state of Arizona for at least a year with carbon-free electricity, he said.

"As the global outlook for clean, carbon-free nuclear energy strengthens and the U.S. moves away from Russian uranium supply, the demand for domestically sourced uranium is growing," Moore said.

Energy Fuels, which also is prepping two more mines in Colorado and Wyoming, was awarded a contract in 2022 to sell $18.5 million in uranium concentrates to the U.S. government to help establish the nation's strategic reserve for when supplies might be disrupted.

Amid the growing appetite for uranium, a coalition of Native Americans testified before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in late February, asking the panel to pressure the U.S. government to overhaul outdated mining laws and prevent further exploitation of marginalized communities.

Carletta Tilousi, who served for years on the Havasupai Tribal Council, said she and others have written countless letters to state and federal agencies and have sat through hours of meetings with regulators and lawmakers. Her tribe's reservation lies in a gorge off the Grand Canyon.

"We have been diligently participating in consultation processes," she said. "They hear our voices. There's no response."

Numerous legal challenges aimed at stopping the Pinyon Plain Mine repeatedly have been rejected by the courts, and top officials in the Biden administration are reticent to weigh in beyond speaking generally about efforts to improve consultation with Native American tribes.

It's just the latest battle over energy development and sacred lands, as tribes in Nevada and Arizona are fighting the federal government over the mining of lithium and the siting of renewable energy transmission lines.

The Havasupai are concerned mining could affect water supplies, wildlife, plants and geology throughout the Colorado Plateau, and the Colorado River flowing through the Grand Canyon and its tributaries are vital to millions of people across the West.

For the Havasupai, their water comes from aquifers deep below the mine.

The Pinyon Plain Mine, formerly known as the Canyon Mine, was permitted in 1984. With existing rights, it was grandfathered into legal operation despite a 20-year moratorium placed on uranium mining in the Grand Canyon region by the Obama administration in 2012.

The U.S. Forest Service in 2012 reaffirmed an environmental impact statement that had been prepared for the mine years earlier, and state regulators signed off on air and aquifer protection permitting within the last two years.

"We work extremely hard to do our work at the highest standards," Moore said. "And it's upsetting that we're vilified like we are. The things we're doing are backed by science and the regulators."

The regional aquifers feeding the springs at the bottom of the Grand Canyon are deep — around 304 meters (nearly 1,000 feet) below the mine — and separated by nearly impenetrable rock, Moore said.

State regulators also have said the area's geology is expected to provide an element of natural protection against water from the site migrating toward the Grand Canyon.

Still, environmentalists say the mine raises bigger questions about the Biden administration's willingness to adopt favorable nuclear power policies.

Using nuclear power to reach emissions goals is a hard sell in the western U.S. From the Navajo Nation to Ute Mountain Ute and Oglala Lakota homelands, tribal communities have deep-seated distrust of uranium companies and the federal government as abandoned mines and related contamination have yet to be cleaned up.

Taylor McKinnon, the Center for Biological Diversity's Southwest director, said allowing mining near the Grand Canyon "makes a mockery of the administration's environmental justice rhetoric."

"It's literally a black eye for the Biden administration," he said.

Teracita Keyanna with the Red Water Pond Road Community Association got choked up while testifying before the human rights commission in Washington, D.C., saying federal regulators proposed keeping onsite soil contaminated by past operations in New Mexico rather than removing it.

"It's really unfair that we have to deal with this and my children have to deal with this and later on, my grandchildren have to deal with this," she said. "Why is the government just feeling like we're disposable. We're not."

In Congress, some lawmakers who come from communities blighted by past contamination are digging in their heels.

Congresswoman Cori Bush of Missouri said during a congressional meeting in January that lawmakers can't talk about expanding nuclear energy in the U.S. without first dealing with the effects that nuclear waste has had on minority communities. In Bush's district in St. Louis, waste was left behind from the uranium refining required by the top-secret Manhattan Project.

"We have a responsibility to both fix — and learn from — our mistakes," she said, "before we risk subjecting any other communities to the same exposure."

Native American News Roundup, March 24-30, 2024

Supreme Court rejects "cancel culture" case

The U.S. Supreme Court this week declined to hear former Kentucky high school student Nick Sandmann's case against several major media outlets for their coverage of his encounter with an Omaha tribe member at an anti-abortion rally in Washington.

Sandmann was part of a Catholic high school group attending the 2019 March for Life rally at the Lincoln Memorial. After a video of his face-to-face encounter with activist Nathan Phillips went viral, his family filed lawsuits against The New York Times, The Washington Post and other major media groups, accusing them of defamatory media reports.

Sandmann argued that his reputation was harmed by media reports of his interaction with Phillips, who was taking part in the Indigenous People's March at the same location.

In Sandmann's appeal to the Supreme Court, his lawyer said the case has "come to epitomize the high-water mark of the 'cancel culture.'" He also said Sandmann went from a "quiet, anonymous teenager into a national social pariah, one whose embarrassed smile in response to Phillips' aggression became a target for anger and hatred."

Read more:

South Dakota governor calls on feds to audit tribes in state

South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem this week called on the Biden administration to conduct "public and comprehensive single audits" of all federal funds that have been given to the nine Native American tribes in that state.

In a statement released Tuesday, Noem said the audits would verify the need for the federal government to provide tribes with additional law enforcement resources.

"Law enforcement in Indian Country is failing to meet basic safety needs," Noem said. "For years, the level of actual funding drastically underestimates the true breadth of the challenges of Indian Country, made worse by the failed border policies of the Biden administration and exacerbated by the presence of drug cartel operations on South Dakota tribal reservations."

Single Audits, formerly known as OMB Circular A-133 audits, are required from all nonfederal entities — including tribes — that receive and spend $750,000 or more of federal financial assistance within a fiscal year, to make sure funds are being used effectively.

In two town hall meetings held on March 13, Noem alleged that Mexican drug cartels are operating on tribal lands in South Dakota and suggested tribal leaders may be benefiting from drug and sex trafficking.

In a statement released March 16, Oglala Sioux Tribe President Frank Star suggested that the governor should "clean up her own backyard" and stop insinuating that all drug trafficking comes from the Sioux reservations."

Read more:

Montana high court says laws restricting voting are unconstitutional

Montana's Supreme Court this week struck down four bills including two which would have made it harder for Native Americans to participate in elections.

These included a bill that would have cut off same-day voter registration and another that would stop the paid collection and submission of absentee ballots by third parties, a method of voting common in remote rural areas and on tribal reservations.

The decision affirms a September 2022 district court decision ruling both laws as unconstitutional.

Plaintiffs Western Native Voice, Montana Native Vote, the Blackfeet Nation, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation, the Fort Belknap Indian Community, and the Northern Cheyenne Tribe filed suit, Western Native Voice v. Jacobsen, against HB 176 and HB 530 in May 2021.

They were represented by the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), the American Civil Liberties Union, the ACLU of Montana and Harvard Law School's Election Law Clinic.

"Today's decision is a resounding win for tribes in Montana who have only ever asked for a fair opportunity to exercise their fundamental right to vote," said NARF staff attorney Jacqueline De León. "Despite repeated attacks on their voting rights, tribes and Native voters in Montana stood strong, and today the Montana Supreme Court affirmed that the state's legislative actions were unconstitutional. Native voices deserve to be heard, and this decision helps ensure that happens."

Read more:

Man pleads guilty to killing eagles in Montana

A Washington state man has pleaded guilty to killing federally protected eagles on an Indian reservation and elsewhere in Montana and conspiring to sell their feathers and other parts in the underground market.

Eagles are protected under two federal laws, the 1940 Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act and the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which bans the taking, buying, selling and transportation of eagles both living and dead, their feathers, eggs and nests.

Native Americans have for centuries used eagle parts and feathers for spiritual and cultural purposes or to mark important achievements. Knowing this, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the 1970s set up the National Eagle Repository, which collects and stores eagles and eagle parts.

Enrolled members of federally recognized tribes may apply for a lifetime religious use permit and order loose feathers, talons and other parts. Schools may also request eagle feathers to present to enrolled tribe members at graduation.

Read more:

Racism, 'Morbid Curiosity' Drove US Museums to Collect Indigenous Remains

In December 1900, John Wesley Powell received “the most unusual Christmas present of any person in the United States, if not in the world,” reported the Chicago Tribune.

The gift for this first director of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of Ethnology was a sealskin sack containing the mummified remains of an Alaska Native.

The sender was a government employee hired to hunt Indian “relics,” who said the remains had been difficult to acquire because “to come into the possession of a dead Indian is a great crime among the Indians.”

The report concluded that it was the only “Indian relic" of this kind at the Smithsonian and it was “beyond money value.”

As it turned out, it was not the museum’s only Alaskan mummy. In 1865, even before the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia, Smithsonian naturalist William H. Dall was hired to accompany an expedition to study the potential for a telegraph route through Siberia to Europe. In his spare time, he looted graves in the Yukon and caves on several Aleutian Islands.

After the U.S. sealed the deal with Russia, the San Francisco-based Alaska Commercial Company won exclusive trading rights and established more than 90 trading posts in Alaska to meet the U.S. demand for ivory and furs.

It also instructed agents “to collect and preserve objects of interest in ethnology and natural history” and forward them to the Smithsonian. Ernest Henig looted 12 preserved bodies and a skull from a cave in the Aleutians in 1874. He donated two to California’s Academy of Science and sent the remainder to the Smithsonian.

More than 30 years after the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act meant to return those remains, a ProPublica investigation last year estimated that more than 110,000 Native American, Native Hawaiian and Alaska Native ancestors remain in public collections across the U.S.

It is not known how many Indigenous remains are closeted in private or overseas collections.

“Museums collected massive numbers, perhaps even millions,” said anthropologist John Stephen “Chip” Colwell, who previously served as curator of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. “Out of the 100 remains we [at the Denver museum] returned, I think only about five or seven individuals were actually even studied.”

So, what sparked this 19th-century frenzy for collecting human remains?

Reconciling science, religion

From the moment they first encountered Indigenous Americans, European thinkers struggled to understand who they were, where they came from, and whether they could be “civilized.”

The Christian bible taught them that all humans descended from Adam and that God created Adam in his own image. So why, Europeans wondered, did Native Americans, Africans and Asians look different?

Some Europeans theorized that all humans were created white, but dietary or environmental differences caused some of them to turn “brown, yellow, red or black.”

Other Europeans refused to accept that they shared a common ancestor with people of color and theorized that God created the races separately before he created Adam.

The birth of scientific racism

Presumptions that compulsory education and Christianization would force Native Americans to abandon their traditional cultures and become “civilized” into mainstream European-American culture proved untrue. So 19th-century scientists turned to advancements in medicine to “prove” the inferiority of Indigenous peoples.

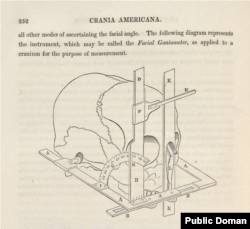

“That’s when you see scientists like Samuel Morton, who invented a pseudoscience trying to place peoples within these social hierarchies based on their biology, and they needed bones to solidify those racial hierarchies,” said Colwell, who is editor-in-chief of the online magazine SAPIENS and author of “Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America's Culture.”

Morton was a Philadelphia physician who collected hundreds of human skulls of all races, mostly Native American, that were forwarded to him by physicians on the frontier. In his 1839 book "Crania Americana," Morton classified human races based on skull measurements. Morton's conclusions were used to support racist ideologies about the inferiority of non-white humans.

“They are not only averse to the restraints of education, but for the most part incapable of a continued process of reasoning on abstract subjects,” he wrote of Native Americans. “The structure of [the Native] mind appears to be different from that of the white man, nor can the two harmonise in their social relations except on the most limited scale.”

Despite Morton’s legacy as an early figure in scientific racism — ideologies that generate pseudo-scientific racist beliefs — his work earned him a reputation at the time as “a jewel of American science” and influenced the field of anthropology and public policy for decades.

In 1868, for example, the U.S. Surgeon General turned his attention away from the Civil War to the so-called “Indian wars” and instructed field surgeons to collect Native American skulls and weapons and send them to the Army Medical Museum in Washington “to aid in the progress of anthropological science.”

“For museums, especially the early years of collecting, it was a form of trophy keeping, a competition between museums,” Colwell told VOA. “And some of it was a competition between national governments to accumulate big collections to demonstrate their global and imperial aspirations.”

All the rest, he said, were fragments of morbid curiosity.

Native American News Roundup, March 10-16, 2024

Here are some of the Native American-related stories in the news this past week:

South Dakota governor: Some tribal leaders "benefiting" from drug cartels

Addressing a town hall meeting in Winner, South Dakota, this week, Governor Kristi Noem described the U.S.-Mexico border as a “war zone” and suggested that drug cartels may be using Indian reservations as a base of operations.

“Mexican cartels are set up here in South Dakota … on our tribal reservations, trafficking drugs and kids and sex trafficking out of South Dakota throughout the Midwest,” she said. “And we've got some tribal leaders that I believe are personally benefiting from the cartels being there, and that's why they attack me every day.”

Her remarks echoed those she made in a January 31 speech before a joint session of state lawmakers, expressing her willingness to send razor wire and National Guard troops to Texas to help defend its border with Mexico.

The Oglala Sioux Tribe, or OST, later banned Noem from the Pine Ridge Reservation.

“Only entry plus enmity constitutes an invasion,” OST President Frank Star Comes Out said in a statement posted on Facebook, accusing Noem of attempting to curry favor with former President Donald Trump.

Noem has been named as a potential running mate for Trump. At Wednesday’s town hall, she acknowledged being on a short list of candidates.

Read more:

Lawsuit aims to hold Arizona health agencies accountable for deaths in fake sober homes

A Phoenix, Arizona, law firm has filed a pair of wrongful death lawsuits against Arizona health care agencies on behalf of two Navajo men who died while in the care of fraudulent sober living homes.

The lawsuits claim the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System and the Arizona Department of Health Services are legally at fault for the deaths of two Navajo citizens who fell victim to "bad actors" seeking to defraud Arizona's health care system by billing for addiction treatment services that were never provided. The lawsuits allege that state agencies knew about the massive fraud but continued to pay home operators “exorbitant rates and amounts of money.”

Read more:

Indigenous father to school board: Allow my son to wear his eagle feather

A Native American high school senior has won the right to wear an eagle feather to graduation ceremonies in June after his father, Stephen White Eagle, successfully argued his case before a Tennessee school board.

“My son and I have been told that his religious beliefs do not fit into the school’s policy. And that is unfair and unconstitutional,” said White Eagle. He and his son are Southern Cheyenne and enrolled citizens of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, many schools across the country ban the wearing of eagle feathers or other regalia at graduation, saying it violates their dress codes.

Eagle feathers, a symbol of strength and achievement, are often given to youth when they reach important milestones in life.

"You cannot pick and choose which religions you want to honor and respect in schools,” White Eagle told VOA via Facebook this week. “If you allow one religion, especially Christianity or Catholicism — both foreign religions to these lands — then you must allow the original religion, that being, of the Indigenous Native American peoples.”

White Eagle said he believes all Americans should work together to respect and honor all races, all colors and all creeds — and “set an example for future generations.”

Read more:

Osage songwriter, drum and dancers perform at 96th annual Academy Awards ceremony

Osage songwriter Scott George, singers, dancers and drum keepers performed "Wahzhazhe” (“Song for My Osage People”) Sunday at the Academy Awards ceremony.

George, a citizen of the Osage Nation in Oklahoma, co-wrote the song with Osage Language expert Vann Bighorse for Best Picture nominee “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

The lyrics are: “Wahzhazhe no-zhin te-tha-bey, Wa-kon-da they-tho gah-ka-bey (Osage people, stand and be recognized. God made it for us)."

The composer wanted to evoke the style of traditional I’n-Lon-Schka (“Playground of the First Son”) dances, held on weekends each June, said George E. "Tink" Tinker, an Osage citizen and professor emeritus of American Indian Cultures at Iliff School of Theology.

“He could not merely take a song from the ceremony and sing it, so he wrote this song to mimic the style of the songs sung in the ceremony without violating the ceremony itself,” he said.

The dance was brought to the Osage by the Kansa (Kaw) Nation after the Osage were forced from Kansas to Oklahoma in the late 19th century.

“These dances mark the coming together of community today and continue as one of the only full-community ceremonies to have survived colonial invasion,” Tinker explained.

Separately, “Killers” lead actress Lily Gladstone, who won a Golden Globe Award and a Screen Actors Guild Award earlier this year, was nominated for this year’s Oscar for Best Actress but did not win.

She reacted gracefully on X: “Feeling the love big time today, especially from Indian Country. Kitto”kuniikaakomimmo”po’waw — seriously, I love you all.”

US Interior Department to Give Tribal Nations $120 Million to Fight Climate-Related Threats

The Biden administration will be allocating more than $120 million to tribal governments to fight the impacts of climate change, the Department of the Interior announced Thursday. The funding is designed to help tribal nations adapt to climate threats, including relocating infrastructure.

Indigenous peoples in the U.S. are among the communities most affected by severe climate-related environmental threats, which have already negatively impacted water resources, ecosystems and traditional food sources in Native communities in every corner of the U.S.

"As these communities face the increasing threat of rising seas, coastal erosion, storm surges, raging wildfires and devastation from other extreme weather events, our focus must be on bolstering climate resilience, addressing this reality with the urgency it demands, and ensuring that tribal leaders have the resources to prepare and keep their people safe is a cornerstone of this administration," Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, said in a Wednesday press briefing.

Indigenous peoples represent 5% of the world's population, but they safeguard 80% of the world's biodiversity, according to Amnesty International. In the U.S., federal and state governments are relying more on the traditional ecological knowledge of Indigenous peoples to minimize the ravages of climate change, and Haaland said ensuring that trend continues is critical to protecting the environment.

"By providing these resources for tribes to plan and implement climate risk, implement climate resilience programs in their own communities, we can better meet the needs of each community and support them in incorporating Indigenous knowledge when addressing climate change," she said.

The department has adopted a policy on implementing Indigenous knowledge, said Assistant Secretary of the Interior Bryan Newland, a citizen of the Bay Mills Indian Community. "We are also investing in tribes' ability to use their knowledge to solve these problems and address these challenges close to home," he said.

The funding will come from President Joe Biden's Investing in America agenda, which draws from the Inflation Reduction Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and annual appropriations.

The funding is the largest annual amount awarded through the Tribal Climate Resilience Annual Awards Program, which was established in 2011 to help tribes and tribal organizations respond to climate change. It will go toward the planning and implementation projects for climate adaptation, community-led relocation, ocean management, and habitat restoration.

The injection of federal funding is part of Biden's commitment to working with tribal nations, said Tom Perez, a senior adviser to the president, and it underscores the administration's recognition that in the past the U.S. has left too many communities behind. "We will not allow that to happen in the future," he said.

In 2022, the administration committed $135 million to 11 tribal nations to relocate infrastructure facing climate threats like wildfires, coastal erosion and extreme weather. It could cost up to $5 billion over the next 50 years to address climate-related relocation needs in tribal communities, according to a 2020 Bureau of Indian Affairs study.

Native American News Roundup, March 3-9, 2024

Some U.S. states restrict Native American access to voting

Congress granted Indigenous Americans citizenship 100 years ago, but some states are passing laws making it hard for them to register to vote or access polling places. Human Rights Watch on Monday urged U.S. states to take active steps to ensure that Native Americans and other voters of color can cast their ballots this election year.

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, 23 states have enacted 53 voting laws making it easier to vote. That said, at least 14 states in 2023 passed restrictive voter laws, and at least six states enacted election interference laws.

Read more:

Chippewa attorney seeks to overturn ICWA

Imprint News this week profiles a Native American attorney who spent years supporting the Indian Child Welfare Act, or ICWA, and is now working to see the law overturned.

Congress passed the ICWA in 1978 to stop states from placing Native American children in the welfare system with non-Native American families — a long-term practice Native Americans decried as an extension of historic assimilation policies.

Attorney Mark Fiddler, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians in Minnesota, was an avid supporter of the law — until, that is, a case he argued back in 1994: After arguing a case against an Indigenous girl’s adoption into a white home, he was troubled to see she was later cycled through dozens of Indigenous foster homes.

“In my heart of hearts, I knew that was probably not the right thing for the child. And it always nagged me,” he said. “My personal opinion is that ICWA has outlived its usefulness and causes more problems than it solves.”

Now, he is arguing a case in the Minnesota appeals court involving a pair of toddler twins who were removed from a white foster family and placed with their mother’s cousin.

Read more:

Seminole Nation attorney named to missing and murdered cases team

The U.S. Justice Department has appointed Bree R. Black Horse, an enrolled member of the Seminole Nation in Oklahoma, as an assistant United States attorney in the department’s new Missing and Murdered Indigenous People, or MMIP, regional program, assigned to prosecute such cases throughout the Northwest region — Washington, Oregon, Montana, Idaho and California.

Black Horse, a 2013 graduate of the Seattle University School of law, most recently served as an associate on the Native American Affairs team of the multinational law firm Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton. Prior to that, she was a public defender for the Yakama Nation in Washington state.

“For far too long Indigenous men, women and children have suffered violence at rates higher than many other demographics,” Black Horse said in a statement. “As I step into this role, I look forward to working with our local, state and tribal partners to identify concrete ways of reducing violence and improving public safety in Indian country and elsewhere.”

In June 2023, the Justice Department announced it would dedicate five MMIP assistant U.S. attorneys and five MMIP coordinators to provide specialized support to U.S. attorneys’ offices addressing and fighting MMIP by investigating unsolved cases and related crimes, boosting communication, coordination and collaboration among federal, tribal, state and local law enforcement and nongovernmental partners.

Black Horse will be attached to the Yakima, Washington, field office.

Read more:

Arizona hoop dancer wins top prize

Josiah Enriquez, a 21-year-old hoop dancer from the Pueblo of Pojoaque in New Mexico, has won the Heard Museum’s 2024 Hoop Dance World Championship, held in Phoenix, Arizona, beating out more than 100 other contestants.

Although its exact origin is unclear, Indigenous peoples have practiced the dance for centuries.

Dancers incorporate circular hoops into their movements and are judged for their grace and style.

Enriquez began dancing at the age of 3, and as the video below shows, he has mastered the art.

Native American News Roundup, Feb. 25-March 2, 2024

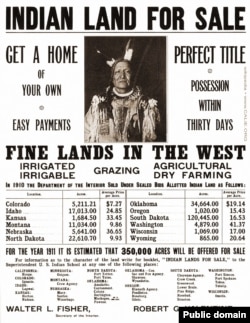

Ten US states control and profit from federal Indian reservation lands

It is commonly assumed that the U.S. government holds in trust all land inside Indian reservation borders for the exclusive use of tribes.

This week, High Country News and the nonprofit online news magazine Grist report that 10 state governments hold trust to 647,500 hectares (1.6 million acres) of surface and subsurface acres of lands inside 83 federal Indian reservations.

Tribes have little to no say over how the lands are used, and state-run mining, grazing, logging and leasing generate millions of dollars that are used to support non-Indigenous agencies such as public schools, prisons or universities.

In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act, or Dawes Act, carving up reservations into smaller parcels that were doled out to families and individuals. The remaining land — about 36,400,000 hectares (90 million acres) — was sold or opened up to U.S. states, settlers and federal projects such as state parks.

States are legally obliged to make money from state trust lands, so there is no incentive for them to turn land back over to tribes “without something in exchange.” Some tribes, such as the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana, have negotiated land back. Others have purchased land back a parcel at a time.

Read more:

ProPublica focuses on museums that got a head start on NAGPRA compliance

As part of its ongoing series examining institutions’ failure to comply with the 1990 Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, ProPublica reports this week on two museums that have met most or all their obligations under NAGPRA, which forbids federally funded institutions from retaining human remains and artifacts without permission from tribes.

They are the Museum of Us in San Diego, California, and the History Colorado Center in Denver, both of which got an earlier start than other institutions in cataloging their holdings and consulting with tribes on how remains and funerary artifacts should be managed and repatriated.

In 2018, three decades after NAGPRA was passed, the Museum of Us — then known as the San Diego Museum of Man — released new “Colonial Pathways” guidelines, acknowledging that it had “long prevented the return of cultural resources to Indigenous communities.”

At the time, the museum estimated that at least 80% of its 75,000 “ethnographic items” would require consultation with descendant tribal communities. The museum admitted that it had “long prevented the return of cultural resources to Indigenous communities.”

That process is ongoing, but in Denver, the History Colorado Center has already repatriated all items subject to NAGPRA. It also loans items back out to tribes on request and allows tribes to change their minds and reclaim items.

Read more:

Editorial: Repatriation does not erase Native Americans’ cultures

In an opinion piece this week, Native News Online editor Levi Rickert writes that while museums are making moves to comply with NAGPRA, he believes some “conservative columnists, politicians and benefactors” are pushing back against revised regulations that require them to obtain tribal or lineal descendants’ consent before exhibiting or conducting research on human remains and related cultural items.

“Since 1492, non-Natives have continually sought to research, examine and showcase our continent’s Indigenous peoples,” Rickert writes. “This fascination led to museums collecting hundreds of thousands of Native cultural artifacts and the remains of deceased Indigenous people — also known as our ancestors.”

He notes that while museums are making moves to comply with NAGPRA’s updated rules, some conservatives criticize the rules as part of the so-called “woke” or liberal political agenda and accuse the Interior Department of erasing Indigenous history.

“If conservative columnists, politicians and benefactors truly want to ensure that Native Americans are not erased, they should stop 'fixating on our ancestors’ bones” and instead focus on honoring treaties and funding health care and education to ensure Native Americans can live 'in modest prosperity.'”

Read the editorial here:

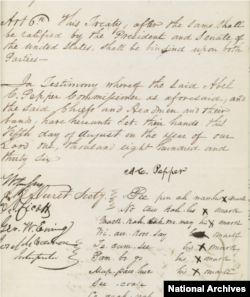

Portrait of 18th-century Mohawk diplomat scores big at auction

An engraved portrait of early Mohawk leader Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Riow fetched nearly $39,000 at auction on Sunday. Engraved by London printmaker John Faber the Elder, it depicts a sachem also known as John of Canajoharie (New York), who was one of a delegation of four Haudenosaunee political representatives who in 1709 set sail for London to negotiate an alliance against the French in the Great Lakes region.

In London, the so-called “Four Kings” — three Mohawk sachems and a Mahican — were wined, dined and celebrated in style.

The engraving was part of an extensive collection of prints by Old Masters collected by wealthy 19th-century Arlington, Massachusetts, citizen Winfield Robbins. Fearing that photography would eventually replace the Old World arts of printmaking, Robbins spent years abroad amassing a collection of tens of thousands of prints and other works of art.

US Court Ruling Could Allow Mine on Land Sacred to Apaches

An Apache group that has fought to protect land it considers sacred from a copper mining project in central Arizona suffered a significant blow Friday when a divided federal court panel voted 6-5 to uphold a lower court's denial of a preliminary injunction to halt the transfer of land for the project.

The Apache Stronghold organization has hoped to halt the mining project by preventing the U.S. government from transferring the land called Oak Flat to Resolution Copper.

Wendsler Nosie, who has led Apache Stronghold's fight, vowed to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court the decision by the rare 11-member "en banc" panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

"Oak Flat is like Mount Sinai to us — our most sacred site, where we connect with our Creator, our faith, our families and our land," Nosie said. "Today's ruling targets the spiritual lifeblood of my people, but it will not stop our struggle to save Oak Flat."

Apache Stronghold represents the interests of certain members of the San Carlos Apache Tribe. The Western Apaches consider Oak Flat, which is dotted with ancient oak groves and traditional plants, essential to their religion.

Oak Flat also sits atop the world's third-largest deposit of copper ore, and there is significant support in nearby Superior and other traditional mining towns in the area for a new copper mine and the income and jobs it could generate.

An environmental impact survey for the project was pulled back while the U.S. Department of Agriculture consulted for months with Native American tribes and others about their concerns.

Apache Stronghold had sued the government to stop the land transfer, saying it would violate its members' rights under the free exercise clause of the First Amendment, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and an 1852 treaty between the United States and the Apaches.

The majority opinion of the appeals panel said that "Apache Stronghold was unlikely to succeed on the merits on any of its three claims before the court, and consequently was not entitled" to a preliminary injunction.

The dissenting five judges said the majority had "tragically" erred and will allow the government to "obliterate Oak Flat."

Apache Stronghold, represented by the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, has 90 days to appeal to the Supreme Court.

"Blasting a Native American sacred site into oblivion is one of the most egregious violations of religious freedom imaginable," said Luke Goodrich, vice president and senior counsel at Becket. "The Supreme Court has a strong track record of protecting religious freedom for people of other faiths, and we fully expect the Court to uphold that same freedom for Native Americans who simply want to continue core religious practices at a sacred site that has belonged to them since before the United States existed."

Vicky Peacey, Resolution Copper president and general manager, welcomed the ruling, saying there was significant local support for the project, which has the potential to supply up to one quarter of U.S. copper demand.

Peacey said it could bring as much as $1 billion a year to Arizona's economy and create thousands of local jobs in a traditional mining region.

"As we deliver these benefits to Arizona and the nation, our dialogue with local communities and tribes will continue to shape the project as we seek to understand and address the concerns that have been raised, building on more than a decade of government consultation and review," Peacey said.

U.S. Representative Raul M. Grijalva, an Arizona Democrat, called the court's decision "wrong."

"Tribal communities deserve the same religious freedom protections for their sacred sites that are respected for every other American," Grijalva said. "The court acknowledges that foreign-owned Resolution Copper will completely and irreversibly desecrate Oak Flat, but they're giving them the green light anyways.

"It's a slap in the face to tribal sovereignty and the many tribes, including the San Carlos Apache, who have been fighting to protect a site they have visited and prayed at since time immemorial," he said.

US Plans Clean Energy Projects for Native American Tribes, Rural Areas

The federal government will fund 17 projects across the United States to expand access to renewable energy on Native American reservations and in other rural areas, the Biden administration announced Tuesday.

The $366 million plan will fund solar, battery storage and hydropower projects in sparsely populated regions where electricity can be costly and unreliable. The money comes from a $1 trillion infrastructure law President Joe Biden signed in 2021.

About a fifth of homes in the Navajo Nation — located in northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico and southeastern Utah — do not have access to electricity, the U.S. Department of Energy estimates. Nearly a third of homes that have electricity on Native American reservations in the U.S. report monthly outages, according to the Biden administration.

The announcement comes as Native tribes in Nevada and Arizona fight to protect their lands and sacred sites amid the Biden administration's expansion of renewable energy. It also comes days after federal regulators granted Native American tribes more authority to block hydropower projects on their land.

The Biden administration will secure funding for the 17 projects only after negotiating with project applicants, federal officials said. Officials from the Department of Energy prepared to meet with tribal leaders to discuss clean energy projects at a summit in Southern California.

"President Biden firmly believes that every community should benefit from the nation's historic transition to a clean energy future, especially those in rural and remote areas," U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said in a statement.

The projects span 20 states and involve 30 tribes. They include $30 million to provide energy derived from plants to wildfire-prone communities in the Sierra Nevada mountains in California and $32 million to build solar and hydropower to a Native American tribe in Washington state.

Another $27 million will go toward constructing a hydroelectric plant to serve a tribal village in Alaska, while $57 million will provide solar power and storage for health centers in rural parts of the Southeast, including in Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina.

Anthropologist Challenges Return of Native American Remains

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act requires federally funded institutions to catalogue, report and return Native American ancestral remains and funerary objects.

With exemptions for cases in which institutions can prove legal ownership, the 33-year-old law known as NAGPRA was updated in January with requirements that researchers obtain tribal or lineal descendants’ consent before exhibiting or conducting research on human remains and related cultural items.

While many Indigenous leaders are encouraged by stronger provisions in the law, anthropologist Elizabeth Weiss says the whole thing should be scrapped because repatriating human remains hinders scientific research.

“A research collection’s ability to inform us never, never dies, because you have new hypotheses that can be used to test, and you also have to retest old hypotheses when new methods develop,” the San Jose State University professor told VOA.

What the law says

Weiss argues that NAGPRA undermines the separation of church and state because it gives traditional Native American religious leaders a say over whether and to whom human remains will be returned.

“NAGPRA was passed with the requirement that two of its [seven] committee members must be traditional Indian religious leaders,” she said. “Further, it allows only one type of religious evidence to be used in repatriation — and that's Native American creationism.”

Weiss says the law has led to institutional guidelines for the handling of remains based on what she calls tribal “mythology,” including a provision at her university that blocked people who are menstruating from handling skeletal remains.

“And the more you allow the acceptance of this kind of superstitious pseudo-religion to creep in, the more widespread it becomes,” she says.

In November 2021, San Jose State’s Anthropology Department issued guidelines on the handling of Native American ancestral remains which read, “Menstruating personnel will not be permitted to handle ancestors.”

The university rescinded that in April 2022.

Long history of grave robbing

Niiyokamigaabaw Deondre Smiles, a citizen of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe in Minnesota, is an Indigenous geographer at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada. He says Weiss is misguided.

“On its face, she makes what looks to be [a] convincing and appealing argument that scientists are working for the betterment of humankind and that Indigenous opposition is based in which she terms ‘pseudo-science’ and stifling the process,” he said. “What she doesn't really engage with is a very long history of grave robbing of Indigenous burial sites in the name of science.”

Smiles gave the example of mid-19th Century “craniologist” Samuel Morton who amassed and measured hundreds of human skulls to support his belief in five races, each created separately, whose cranial size determined their place in the racial hierarchy.

“In their mental character, the Americans are averse to cultivation, and slow in acquiring knowledge,” he wrote in his 1839 book, "Crania Americana."

Smiles says, “There's been a really long history of people treating Indigenous remains as just simply objects of curiosity, as things that are made to be studied, rather than belonging to human beings once upon a time.”

NAGPRA previously allowed institutions to retain artifacts they deemed “culturally unidentifiable.” That provision has now been removed, and tribal historians and religious leaders will now have a voice in determining where those items should go.

Attorney Shannon O’Loughlin, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, heads the Association on American Indian Affairs, a nonprofit that helps tribes navigate NAGPRA processes.

“The law is very clear that institutions do not own Native bodies or cultural items unless they can prove a right of possession,” she said. “If some tribes ask for certain accommodations and protocols, that's because they're the true owners.”

O’Loughlin stresses that NAGPRA does not prohibit research or display of Native remains.

“It simply requires consent. The whole point of the law is to bring tribes to the table where they've never been allowed before and to educate museums about items in their collections and why they are significant.”

Anthropologist Challenges Return of Native American Remains

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act requires federally funded institutions to catalog, report and return Native American ancestral remains and funerary objects.

With exemptions for cases in which institutions can prove legal ownership, the 33-year-old law known as NAGPRA was updated in January with requirements that researchers obtain tribal or lineal descendants' consent before exhibiting or conducting research on human remains and related cultural items.

While many Indigenous leaders are encouraged by stronger provisions in the law, anthropologist Elizabeth Weiss says the whole thing should be scrapped because repatriating human remains hinders scientific research.

"A research collection's ability to inform us never, never dies, because you have new hypotheses that can be used to test, and you also have to retest old hypotheses when new methods develop," the San Jose State University professor told VOA.

What the law says

Weiss argues that NAGPRA undermines the separation of church and state because it gives traditional Native American religious leaders a say over whether and to whom human remains will be returned.

"NAGPRA was passed with the requirement that two of its [seven] committee members must be traditional Indian religious leaders," she said. "Further, it allows only one type of religious evidence to be used in repatriation — and that's Native American creationism."

Weiss says the law has led to institutional guidelines for the handling of remains based on what she calls tribal "mythology," including a provision at her university that blocked people who are menstruating from handling skeletal remains.

"And the more you allow the acceptance of this kind of superstitious pseudoreligion to creep in, the more widespread it becomes," she said

In November 2021, San Jose State's Anthropology Department issued guidelines on the handling of Native American ancestral remains that read, "Menstruating personnel will not be permitted to handle ancestors."

The university rescinded that in April 2022.

History of grave robbing

Niiyokamigaabaw Deondre Smiles, a citizen of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe in Minnesota, is an Indigenous geographer at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada. He said Weiss is misguided.

"On its face, she makes what looks to be [a] convincing and appealing argument that scientists are working for the betterment of humankind and that Indigenous opposition is based in which she terms 'pseudoscience' and stifling the process," he said. "What she doesn't really engage with is a very long history of grave robbing of Indigenous burial sites in the name of science."

Smiles gave the example of mid-19th-century "craniologist" Samuel Morton who amassed and measured hundreds of human skulls to support his belief in five races, each created separately, whose cranial size determined their place in the racial hierarchy.

"In their mental character, the Americans are averse to cultivation, and slow in acquiring knowledge," he wrote in his 1839 book, Crania Americana.

Smiles said, "There's been a really long history of people treating Indigenous remains as just simply objects of curiosity, as things that are made to be studied, rather than belonging to human beings once upon a time."

NAGPRA previously allowed institutions to retain artifacts they deemed "culturally unidentifiable." That provision has now been removed, and tribal historians and religious leaders will now have a voice in determining where those items should go.

Attorney Shannon O'Loughlin, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, heads the Association on American Indian Affairs, a nonprofit that helps tribes navigate NAGPRA processes.

"The law is very clear that institutions do not own Native bodies or cultural items unless they can prove a right of possession," she said. "If some tribes ask for certain accommodations and protocols, that's because they're the true owners."

O'Loughlin stressed that NAGPRA does not prohibit research or display of Native remains.

"It simply requires consent. The whole point of the law is to bring tribes to the table where they've never been allowed before and to educate museums about items in their collections and why they are significant."

Native American News Roundup Feb. 4-10, 2024

U.S. Senator Brian Schatz took to the Senate floor on February 1 to demand that museums and federal agencies comply with the law and return to Native American tribes all ancestral remains and funerary objects in their collections.

Passed in 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, directs all federally funded institutions to catalog all Native American human remains, funerary items and objects of cultural significance in their collections, submit the information to a National Park Service database, and work with tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations, or NHOs, to repatriate them.

A January update to NAGPRA now requires institutions to “obtain free, prior and informed consent from lineal descendants, tribes or NHOs before allowing any exhibition of, access to, or research on human remains or cultural items.”

“Give the items back. Comply with federal law. Hurry,” the Hawaii senator said.

Schatz credited institutions that have stepped up repatriation efforts, including Harvard University, the American Museum of Natural History in New York and Chicago’s Field Museum. But tens of thousands of ancestral remains are still in collections covered by the law.

“The U.S. government literally stole people’s bones. Soldiers and agents overturned graves and took whatever they could find. And these weren’t isolated incidents — they happened all across the country,” Schatz said.

"The theft of hundreds of thousands of remains and items over generations was unconscionable in and of itself, but the legacy of that cruelty continues to this day, because these museums and universities continue to hold onto these sacred items in violation of everything that is right and moral — and importantly, in violation of federal law.”

Read more:

Governor, tribal president clash over politics of immigration

Oglala Lakota tribal President Frank Star Comes Out has banned South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation after a speech in which she accused the Biden administration of failing to protect states from an “invasion” of immigrants across the southern border.

“South Dakota is directly affected by this invasion,” she said in a joint address to state lawmakers on January 31. “We are affected by cartel presence on our tribal reservations; by the spread of drugs and human trafficking throughout our communities; and by the drain on our resources at the local, state and federal level.”

Noem invoked the U.S. Constitution and an 18th-century essay by founder Alexander Hamilton to defend states’ rights to send militias to repel invasions. She also said she is willing to send razor wire and South Dakota National Guard troops to Texas to help the state defend its border with Mexico.

“Only entry plus enmity constitutes an invasion,” Star Comes Out countered in a statement posted to Facebook. “The unlawful entry of people into the United States cannot be construed as an invasion.”

He said, "Many of the people coming to the southern border of the United States in search of jobs and a better life are Indian people," including from El Salvador, Guatemala and Mexico, "and don't deserve to be dehumanized and mistreated."

Star Comes Out said Noem wants to campaign on border issues to get former President Donald Trump reelected “and, in turn, increase her chances of being selected by Trump to be his running mate as Vice President."

Noem responded to Star Comes Out’s Facebook post with a statement saying she has worked for years to build relationships with South Dakota tribes and to deliver services to tribal communities, including health care, economic development, social services, housing, food programs, suicide prevention and drug addiction treatment.

“It is unfortunate that President Star Comes Out chose to bring politics into a discussion regarding the effects of our federal government’s failure to enforce federal laws at the southern border and on tribal lands,” Noem said. “My focus continues to be on working together to solve those problems.”

Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders split over US support for Israelis and Palestinians

Polling shows divided opinion on the war in Gaza among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Around half of those surveyed believe the United States is “too supportive” of Israel (48%) and “not supportive enough” (49%) of Palestinians in the current war in Gaza.

AAPI Data and Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs polled 1,091 Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders in early December. Adults ages 60 and older are more likely to view Israel as an ally than younger people in the survey.

About half of AAPI adults view India as primarily a U.S. partner that does not share U.S. interests and values. A majority say Japan is an ally that does share U.S. interests and values, while about one-third of AAPI adults see China as either a rival or an adversary.

The poll is part of an ongoing project exploring the views of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, whose views may not show up in other surveys because of language barriers. Participants were offered the choice to answer questions in English, Mandarin Cantonese, Vietnamese and Korean.

Read more:

Ecologist: Not all Native Americans are ‘exemplary conservationists’

In a lengthy opinion piece published this week on the Wildlife News website, ecologist and writer George Wuerthner disputes what he calls a “false narrative” that Native American tribal groups universally oppose behaviors and practices that are harmful to the environment.

“People are afraid … to suggest that tribal people are like other humans and are capable of good and bad conservation positions,” he wrote. “At the same time, any information that might temper that conclusion is ignored or suppressed.”

He listed dozens of tribal policies and activities that conservationists say harm the environment, including tribal logging projects in several states, wolf and bison kills, and a National Park Service-sanctioned eagle kill in New Mexico.

At least 12 tribes own oil and gas fields on their reservations. The Navajo Nation owns three coal mines in Montana, Wyoming and New Mexico — making it the third-largest U.S. coal company. It also owns a share of a coal-fired power plant and has partnered on a lithium extraction project in Arizona.

While Wuerthner said he recognizes “numerous examples where Indigenous people have promoted environmental protection,” he opposes the Biden administration’s agreements with tribes to co-manage public lands.

Read more:

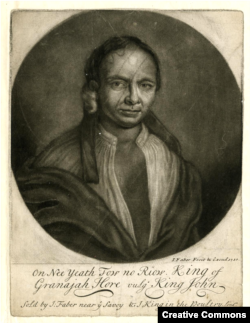

For Native American Activists, the Kansas City Chiefs Have It All Wrong

Rhonda LeValdo is exhausted, but she's refusing to slow down. For the fourth time in five years, her hometown team and the focus of her decadeslong activism against the use of Native American imagery and references in sports is in the Super Bowl.

As the Kansas City Chiefs prepare for Sunday's big game, so does LeValdo. She and dozens of other Indigenous activists are in Las Vegas to protest and demand the team change its name and ditch its logo and rituals they say are offensive.

"I've spent so much of my personal time and money on this issue. I really hoped that our kids wouldn't have to deal with this," said LeValdo, who founded and leads a group called Not In Our Honor. "But here we go again."

Her concern for children is founded. Research has shown the use of Native American imagery and stereotypes in sports have negative psychological effects on Native youth and encourage non-Native children to discriminate against them.

"There's no other group in this country subjected to this kind of cultural degradation," said Phil Gover, who founded a school dedicated to Native youth in Oklahoma City.

"It's demeaning. It tells Native kids that the rest of society, the only thing they ever care to know about you and your culture are these mocking minstrel shows," he said, adding that what non-Native children learn are stereotypes.

LeValdo, an Acoma Pueblo journalist and faculty member at Haskell Indian Nations University, has been in the Kansas City area for more than two decades.

She arrived from Nevada as a college student. In 2005, when Kansas City was playing Washington's football team, she and other Indigenous students organized around their anger at the offensive names and iconography used by both teams.

Some sports franchises made changes in the wake of the 2020 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The Washington team dropped its name, which is considered a racial slur, after calls dating back to the 1960s by Native advocates such as Suzan Harjo. In 2021, the Cleveland baseball team changed its name from the Indians to the Guardians.

Ahead of the 2020 season, the Chiefs barred fans from wearing headdresses or face paint referencing or appropriating Native American culture in Arrowhead Stadium, although some still have.

"End Racism" was written in the end zone. Players put decals on their helmets with similar slogans or names of Black people killed by police.

"We were like, 'Wow, you guys put this on the helmets and on the field, but look at your name and what you guys are doing,'" LeValdo said.

The next year, the Chiefs retired their mascot, a horse named Warpaint that a cheerleader would ride onto the field every time the team scored a touchdown. In the 1960s, a man wearing a headdress rode the horse.

The team's name and arrowhead logo remain, as does the "tomahawk chop," in which fans chant and swing a forearm up and down in a ritual that is not unique to the Chiefs.

The added attention on the team this season thanks to singer Taylor Swift's relationship with tight end Travis Kelce isn't lost on Indigenous activists. LeValdo said her fellow activists made a sign for this weekend reading, "Taylor Swift doesn't do the chop. Be like Taylor."

"We were watching. We were looking to see if she was going to do it. But she never did," LeValdo said.

The Chiefs say the team was named after Kansas City Mayor H. Roe Bartle, who was nicknamed "The Chief" and helped lure the franchise from Dallas in 1963.

They also say they have worked in recent years to eliminate offensive imagery.

"We've done more over the last seven years, I think, than any other team to raise awareness and educate ourselves," Chiefs President Mark Donovan said ahead of last year's Super Bowl.

The team has made a point to highlight two Indigenous players: long snapper James Winchester, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and center Creed Humphrey, who is from the Citizen Potawatomi Nation of Oklahoma.

In 2014, the Chiefs launched the American Indian Community Working Group, which has Native Americans serving as advisers, to educate the team on issues facing the Indigenous population. As a result, Native American representatives have been featured at games, sometimes offering ceremonial blessings.

"The members of that working group weren't people that were involved in any of the organizations that actually serve Natives in Kansas City," said Gaylene Crouser, executive director of the Kansas City Indian Center, which provides health, welfare and cultural services to the Indigenous community. Crouser is among those who plan to protest in Las Vegas this weekend.

U.S. Representative Emanuel Cleaver, a Democrat, sees the label "Chief" as a term of endearment. He has been a Chiefs fan since he moved to Kansas City more than half a century ago, although he said it "wouldn't bother me that much" if the name were changed.

"A chief was somebody with enormous influence," said Cleaver, who is Black, making a reference to tribal chiefs in Africa. "As long as the name is not an insult or an invective, then I'm OK with it."

The story presented by the Chiefs features the message that the team is honoring Native culture. But Crouser calls that a "PR stunt."

"There's no honor in you painting your face and putting on a costume and cosplaying our culture," Crouser said. "The sheer entitlement of people outside our community telling us they're honoring us is so incredibly frustrating."

LeValdo is very conscious of who gets to own a narrative. As a University of Kansas journalism student in the early 2000s, she said a professor told her she would be too biased as a Native woman to report on stories about Native people. When she entered the world of video journalism, she was told she "didn't have the look" to be on camera.

During Chiefs home games, she and other Indigenous activists stand outside Arrowhead with signs saying, "Stop the Chop" and "This Does Not Honor Us." The sounds of a large drum and thousands of fans imitating a "war chant" as they swing their arms thunder from the stadium.

For LeValdo, the pain fueling her anger and activism is rooted in the oppression, killing and displacement of her ancestors and the lingering effects those injustices have on her community.

"We weren't even allowed to be Native American. We weren't allowed to practice our culture. We weren't allowed to wear our clothes," she said. "But it's OK for Kansas City fans to bang a drum, to wear a headdress and then to act like they're honoring us? That doesn't make sense."