Native Americans

Native American news roundup, June 16-22, 2024

Feds acknowledge dams had ‘devasting impact’ on Pacific Northwest tribes

The Biden-Harris administration has released a report detailing the negative impacts that federal Columbia River dams have had, past and present, on tribal communities in the Pacific Northwest.

The report, part of the Interior Department’s efforts to support tribally led salmon restoration in the Columbia River Basin, is the first comprehensive federal documentation of the harms these dams have inflicted on eight tribal nations in the Pacific Northwest.

The dams have blocked fish migration, flooded sacred lands and transformed ecosystems, resulting in profound losses for tribal communities who have historically relied on salmon and other fish for both sustenance and cultural practices.

“Since time immemorial, Tribes along the Columbia River and its tributaries have relied on Pacific salmon, steelhead and other native fish species for sustenance and their cultural and spiritual ways of life,” Secretary Deb Haaland said in a statement.

“Acknowledging the devastating impact of federal hydropower dams on Tribal communities is essential to our efforts to heal and ensure that salmon are restored to their ancestral waters.”

The report includes recommendations to help the federal government fulfill its trust responsibilities and ensure a healthy Columbia River Basin for future generations: first to recognize and address the unique hardships tribes have faced because of federal dam construction in conducting future environmental reviews; to pursue joint stewardship and management agreements with tribes; to continue work to restore and unite fractured homelands, and to incorporate Indigenous knowledge in environmental decision-making.

Read more:

Truth and Healing bill advances in House

The Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act of 2024 has passed markup in the House Education and Workforce Committee, a key step along the path to full passage.

HR 7227, a companion bill to S. 1723 which is sponsored by U.S. Reps. Sharice Davids, Ho-Chunk and a Democrat from Kansas, and Tom Cole, Chickasaw and a Republican from Oklahoma, would create a six-year commission to investigate the federal Indian boarding school system beyond what the Interior Department’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

The commission would be tasked with gathering records from local, state and religious institutions and taking testimony from survivors, tribes and descendants. It would also locate and identify Native children’s graves and document the ongoing impact of the boarding school system on tribes and survivors.

"I would not be here if not for the resilience of my ancestors and those who came before me, including my grandparents, who are survivors of federal Indian Boarding Schools,” said Davids, who co-chairs the Congressional Native American Caucus, said in a statement. “I am glad my colleagues came together today to advance the establishment of a Truth and Healing Commission, bringing survivors, federal partners, and Tribal leaders to the table to fully investigate what happened to our relatives and work towards a brighter path for the next seven generations.”

In a separate statement Cole said he is committed to investigating the abuses of the boarding school era.

“This Commission will hopefully bring these communities one step closer to healing and peace for themselves, their families, and future generations,” he said.

Read more:

Tribe opens its doors to community displaced by wildfires

The Mescalero Apache Tribe in south-central New Mexico this week declared a state of emergency after two wildfires broke out Monday on the northeast corner of their reservation.

Flames quickly spread to the village of Ruidoso and the city of Ruidoso Downs, prompting thousands of mandatory evacuations.

The tribe designated two sites for both tribal and non-tribal evacuees in the area and received a strong response to appeals for donations.

“We are extremely grateful for the willingness of our tribal members, neighboring towns and villages, community groups/organizations and complete strangers for the donations being dropped off at these sites,” the tribe noted on its Facebook page.

So far, the fire has claimed two known lives, burned 9,300 hectares of combined tribal and non-tribal land, and destroyed 1,400 buildings, 500 of them residential.

Railway fined whopping $400 million for trespassing on Native land

A U.S. District Court judge on Monday ordered the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway, or BNSF, to pay the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community in Washington State just under $400 million for intentionally trespassing on their reservation.

A 1991 easement agreement allowed BNSF to run 25 train cars each direction per day and required BNSF to disclose the “nature and identity of all cargo.”

The tribe says in 2012, “unit trains” of 100 railcars or more were crossing the reservation, and by 2015, BNSF was running six 100-car “unit trains” per week across the reservation to a nearby refinery.

This resulted in significant profits, with revenues from the trespassing cars totaling about $900 million. During a recent four-day bench trial, both parties provided expert testimony on how to calculate the proportion of these profits that should be paid to the tribe.

“We know that this is a large amount of money. But that just reflects the enormous wrongful profits that BNSF gained by using the Tribe’s land day after day, week after week, year after year over our objections,” said Swinomish tribal chairman Steve Edwards. “When there are these kinds of profits to be gained, the only way to deter future wrongdoing is to do exactly what the court did today – make the trespasser give up the money it gained by trespassing.”

Read more:

US acknowledges Northwest dams have devastated the region's Native tribes

The U.S. government on Tuesday acknowledged, for the first time, the harmful role it has played over the past century in building and operating dams in the Pacific Northwest — dams that devastated Native American tribes by inundating their villages and decimating salmon runs while bringing electricity, irrigation and jobs to nearby communities.

In a new report, the Biden administration said those cultural, spiritual and economic detriments continue to pain the tribes, which consider salmon part of their cultural and spiritual identity, as well as a crucial food source.

The government downplayed or accepted the well-known risk to the fish in its drive for industrial development, converting the wealth of the tribes into the wealth of non-Native people, according to the report.

"The government afforded little, if any, consideration to the devastation the dams would bring to Tribal communities, including to their cultures, sacred sites, economies, and homes,” the report said.

It added: “Despite decades of efforts and an enormous amount of funding attempting to mitigate these impacts, salmon stocks remain threatened or endangered and continued operation of the dams perpetuates the myriad adverse effects.”

The Interior Department's report comes amid a $1 billion effort announced earlier this year to restore the region’s salmon runs before more become extinct — and to better partner with the tribes on the actions necessary to make that happen.

That includes increasing the production and storage of renewable energy to replace hydropower generation that would be lost if four dams on the lower Snake River are ever breached. Tribes, conservationists and even federal scientists say that would be the best hope for recovering the salmon, providing the fish with access to hundreds of miles of pristine habitat and spawning grounds in Idaho.

“President Biden recognizes that to confront injustice, we must be honest about history – even when doing so is difficult,” said a statement from White House Council on Environmental Quality Chair Brenda Mallory and Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American cabinet secretary. “In the Pacific Northwest, an open and candid conversation about the history and legacy of the federal government’s management of the Columbia River is long overdue.”

Northwest Republicans in Congress and some business and utility groups oppose breaching the dams, saying it would jeopardize an important shipping route for farmers and throw off clean-energy goals. GOP Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, who represents eastern Washington, called Tuesday's report a “sham."

“This bad faith report is just the latest in a long list of examples that prove the Biden administration’s goal has always been dam breaching," she said in a written statement.

The document was a requirement of an agreement last year to halt decades of legal fights over the operation of the dams. It lays out how government and private interests in the early 20th century began walling off the tributaries of the Columbia River, the largest in the Northwest, to provide water for irrigation or flood control, compounding the damage that was already being caused to water quality and salmon runs by mining, logging and rapacious non-tribal salmon cannery operations.

The report was accompanied by the announcement of a new task force to coordinate salmon recovery efforts across federal agencies.

Tribal representatives said they were gratified with the administration’s formal, if long-belated, acknowledgment of how the U.S. government ignored their treaty-based fishing rights and their concerns about how the dams would affect their people.

“The salmon themselves have been suffering the consequences since the dams first were put in,” said Shannon Wheeler, chairman of the Nez Perce Tribe. “The lack of salmon eventually starts affecting us, but they're the ones who have been suffering the longest. ... It feels like there's an opportunity to end the suffering.”

Salmon are born in rivers and migrate far downstream to the ocean, where they spend their adult lives before returning to their natal rivers to spawn and die. Dams can disrupt that by cutting off access to upstream habitat and by slowing and warming water to the point that fish die.

The Columbia River Basin, an area roughly the size of Texas, was once the world’s greatest salmon-producing river system, with as many as 16 million salmon and steelhead returning every year to spawn.

Now, scientists say, about 2 million salmon and steelhead return to the Columbia and its tributaries each year, about two-thirds of them hatchery raised. The Shoshone-Bannock Tribe in southeastern Idaho said it once harvested enough salmon for each tribal member to have 700 pounds of fish in a year. Today, the average harvest yields barely 1 pound per tribal member.

Of the 16 stocks of salmon and steelhead that once populated the river system, four are extinct and seven are listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Another iconic but endangered Northwest species, a population of killer whales, also depend on the salmon.

There has been growing recognition across the U.S. that the harms some dams cause to fish outweigh their usefulness. Dams on the Elwha River in Washington state and the Klamath River along the Oregon-California border have been or are being removed.

The construction of the first dams on the main Columbia River, including the Grand Coulee and Bonneville dams in the 1930s, provided jobs to a country grappling with the Great Depression, as well as hydropower and navigation.

As early as the late 1930s, tribes were warning that the salmon runs could disappear, with the fish no longer able to access spawning grounds upstream. The tribes — the Yakama Nation, Spokane Tribe, confederated tribes of the Colville and Umatilla reservations, Nez Perce, and others — continued to fight the construction and operation of the dams for generations.

Tom Iverson, regional coordinator for Yakama Nation Fisheries, said that while the report was gratifying, it remains “hopes and promises” until funding for salmon restoration and renewable power projects comes through Congress.

“With these agreements, there is hope," Iverson said. "We feel like this is a moment in time. If it doesn’t happen now, it will be too late.”

Despite gains, Native Americans still face voting barriers

Native Americans today say they still face barriers to casting their votes, six decades after U.S. President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act.

Many live miles away from voter registration and polling sites and lack access to reliable transportation.

Others may not have traditional mailing addresses and cannot satisfy voter registration requirements. Voting by mail can be “iffy,” according to O.J. Semans, a Sicangu Lakota citizen living on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota and co-executive director of Four Directions, a voting rights advocacy group that has worked on behalf of tribes in several states.

“You must remember, the old Pony Express [mail delivery on horseback] wasn’t meant for reservations. It was for outposts and settler towns,” Semans said. “The U.S. Postal Service has neglected every Indian reservation in the United States when it comes to ensuring we have equality.”

A 2023 study of mail service on the Navajo Nation — the largest reservation in the U.S. — notes that when deciding where to open post offices during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. Postal Service picked locations that would “advance military objectives and serve the interests of Anglo-American settlers.”

“Post Offices are fewer and farther from each other on reservation communities; there are fewer service hours; and we show in a mail experiment that letters posted on reservations are slower and less likely to arrive," the study said.

Post offices exist on Seman’s Rosebud Reservation, but they no longer accept general delivery.

“So, if you want to vote by mail, you can request an absentee ballot and fill it out. But you’d never get the ballot back,” he said.

States pass restrictive laws

The 1965 Voting Rights Act banned traditional forms of voter discrimination such as literacy tests, character assessments and other practices widely used to disenfranchise minority voters.

It authorized the federal government to oversee voter registration and election procedures in certain states and localities with histories of discriminatory practices, and it also required those jurisdictions to obtain “preclearance” from the Justice Department or a federal court before changing voting laws or procedures.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the formula for deciding which localities needed preclearance as unconstitutional, opening the way for states to pass new voting laws.

During a Senate Indian Affairs Committee hearing in 2021, Jacqueline De Leon, an enrolled member of the Isleta Pueblo and a staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund, or NARF, described some conditions for Indigenous voters.

“In South Dakota, Native American voters were forced to vote in a repurposed chicken coop with no bathroom facilities and feathers on the floor,” she testified.

In Wisconsin, Native Americans were required to cast their ballots inside a sheriff’s office.

NARF, tribes fight back

In 2021, President Joe Biden created the Interagency Steering Group on Native American Voting Rights to report on barriers facing Native voters.

“Native American communities have not been immune, but indeed have been packed or divided by district lines that dilute their vote or otherwise discriminate,” the group reported.

In November 2021, North Dakota’s Republican-led legislature approved a new legislative map that separated state House districts on the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation and the Fort Berthold reservation, home to the Three Affiliated Tribes.

The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and Spirit Lake tribes filed a federal lawsuit arguing that the new map violated the Voting Rights Act by packing the Turtle Mountain band — that is, concentrating them into a single electoral district to reduce their influence in other districts, and cracking — or dividing — the Spirit Lake tribe across districts to dilute their voting power.

“A conservative judge found this was a clear violation of the Voting Rights Act,” De Leon told VOA. “And rather than protect its Native constituents where there was a violation, the state has appealed, trying to just block the cost of action as opposed to remediating the discrimination.”

Arizona passed a law in 2022 requiring voters to provide proof of their physical address.

“And that was really an attack on the Native vote because about 40,000 homes in Indian Country in Arizona don't have traditional addresses on them or any way to prove residential location,” De Leon said.

With NARF’s support, the Tohono O’odham Nation and the Gila River Indian Community in 2022 filed suit in U.S. District Court for Arizona. In 2023, the court ruled in their favor, finding that the address requirements violated tribe members’ constitutional right to vote.

With five months to go before November’s general election, Semans said, Indigenous voting rights activists must stay vigilant.

“With this new Supreme Court, even rulings that we got years ago that were positive for Indian country could change before then,” he said. “Things can change on a dime.”

Native American news roundup, June 9-15, 2024

Catholic bishops apologize to Native Americans

The Catholic Church on Friday issued a carefully worded apology to Native Americans for a “history of trauma” caused in part by its “abandonment” of the community.

During their spring assembly in Louisville, Kentucky, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) approved a document titled, “Keeping Christ’s Sacred Promise: A Pastoral Framework for Indigenous Ministry,” which cites “epidemics, national policies, and Native boarding schools” as sources of that trauma.

The 56-page document also notes that “European and Eurocentric world powers” used language from 14th and 15th century public decrees known as Papal bulls to justify the enslavement and mistreatment of Native Americans and dispossession from their lands. “Let us be very clear here: The Catholic Church does not espouse these ideologies,” the document reads.

The document stops short of formally rescinding the bulls, as Indigenous groups have long requested. Nor does the document reference widespread abuse of Indigenous children by Catholic clergy.

“Many Christians have committed evil acts against indigenous peoples for which recent Popes have asked forgiveness on numerous occasions,” it states.

Bishops originally commissioned the document in 2020 but put it on hold in November 2023 concerned that certain language could create liability issues for the Church. The language in question referenced “past sins” and “wounds inflicted on Native peoples” by “some members of the Church,” the Catholic news site The Pillar reported.

Read more:

Florida parole board to decide on clemency for Leonard Peltier

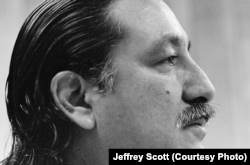

American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier appealed his case before a Florida parole board Monday after having served most of his life in prison.

Peltier, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota, was convicted in 1977 of killing two FBI agents during a 1975 standoff on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences.

Nick Tilsen, president and CEO of the Indigenous-led advocacy group NDN Collective, was allowed to testify at the parole hearing.

“Face to face with the federal government, I got to tell them that Leonard is revered globally as a political prisoner fighting against the unjust systems that oppress our people,” said Tilsen as quoted on the collective’s Facebook page.

Peltier, 79, claims he is innocent of the charges. The parole board is expected to announce their decision in mid-July.

Makah hunters in Washington state to resume whale hunts

The U.S. government announced this week it will allow the Makah Tribe in Washington to resume hunting grey whales, a right guaranteed them by the 1855 Treaty of Neah Bay.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service will allow the Makah Tribe to resume hunting up to 25 Eastern North Pacific gray whales over a 10-year period in U.S. waters.

“This final rule represents a major milestone in the process to return ceremonial and subsistence hunting of Eastern North Pacific gray whales to the Makah Tribe,” said Janet Coit, assistant administrator for NOAA Fisheries. “The measures adopted today honor the Makah Tribe's treaty rights and their cultural whaling tradition that dates back well over 1,000 years and is fundamental to their identity and heritage.”

The Marine Mammal Act of 1972 banned hunting, harassing, capturing or killing any marine mammal and prohibits the import and export of marine mammals and their parts or products.

The Makah Tribe in 2005 asked NOAA for a waiver that would allow them to hunt gray whales for ceremonial and subsistence purposes and to make and sell items created from harvested whales.

Read more:

Rare white buffalo calf of special significance to Lakota

While camping recently in Yellowstone Park’s Lamar Valley, Montana photographer Erin Braaten captured one-of-a-kind photographs of a white buffalo calf moments after it was born.

White buffalo calves are a rarity; though no formal studies have been conducted, cited statistics say only one in 10 billion buffalo is born white.

They have special spiritual significance to Plains tribes and are featured in many traditional stories.

Before his death in 1950, Lakota spiritual leader and visionary Nicholas Black Elk related to author Joseph Epes Brown why: nineteen generations ago, he said, a mysterious holy woman dressed in white buckskin came to Lakota chief Standing (or High) Hollow Horn and presented him a sacred stone pipe. She also taught him the seven spiritual rituals in which it should be used.

“’Always remember how sacred it is, and treat it as such, for it will take you to the end,’” Black Elk quoted her as saying. “’I am leaving now, but I shall look back upon your people in every age and at the end I shall return.” As she left, tradition holds that she transformed into a white buffalo calf.

The pipe has been passed down from one generation to the next. Today, Miniconjou Lakota spiritual leader Arvol Looking Horse is the 19th pipe holder. It was given to him when he was 12.

Read more:

Reported birth of rare white buffalo calf fulfills Lakota prophecy

The reported birth of a rare white buffalo in Yellowstone National Park fulfills a Lakota prophecy that portends better times, according to members of the American Indian tribe who cautioned that it's also a signal that more must be done to protect the earth and its animals.

"The birth of this calf is both a blessing and warning. We must do more," said Chief Arvol Looking Horse, the spiritual leader of the Lakota, Dakota and the Nakota Oyate in South Dakota, and the 19th keeper of the sacred White Buffalo Calf Woman Pipe and Bundle.

The birth of the sacred calf comes as after a severe winter in 2023 drove thousands of Yellowstone buffalo, also known as bison, to lower elevations. More than 1,500 were killed, sent to slaughter or transferred to tribes seeking to reclaim stewardship over an animal their ancestors lived alongside for millennia.

Erin Braaten of Kalispell took several photos of the calf shortly after it was born on June 4 in the Lamar Valley in the northeastern corner of the park.

Her family was visiting the park when she spotted "something really white" among a herd of bison across the Lamar River.

Traffic ended up stopping while bison crossed the road, so Braaten stuck her camera out the window to take a closer look with her telephoto lens.

"I look and it's this white bison calf. And I was just totally, totally floored," she said.

After the bison cleared the roadway, the Braatens turned their vehicle around and found a spot to park. They watched the calf and its mother for 30-45 minutes.

"And then she kind of led it through the willows there," Braaten said. Although Braaten came back each of the next two days, she didn't see the white calf again.

For the Lakota, the birth of a white buffalo calf with a black nose, eyes and hooves is akin to the second coming of Jesus Christ, Looking Horse said.

Lakota legend says about 2,000 years ago — when nothing was good, food was running out and bison were disappearing — White Buffalo Calf Woman appeared, presented a bowl pipe and a bundle to a tribal member, taught them how to pray and said that the pipe could be used to bring buffalo to the area for food. As she left, she turned into a white buffalo calf.

"And some day when the times are hard again," Looking Horse said in relating the legend, "I shall return and stand upon the earth as a white buffalo calf, black nose, black eyes, black hooves."

A similar white buffalo calf was born in Wisconsin in 1994 and was named Miracle, he said.

Troy Heinert, the executive director of the South Dakota-based InterTribal Buffalo Council, said the calf in Braaten's photos looks like a true white buffalo because it has a black nose, black hooves and dark eyes.

"From the pictures I've seen, that calf seems to have those traits," said Heinert, who is Lakota. An albino buffalo would have pink eyes.

A naming ceremony has been held for the Yellowstone calf, Looking Horse said, though he declined to reveal the name. A ceremony celebrating the calf's birth is set for June 26 at the Buffalo Field Campaign headquarters in West Yellowstone.

Other tribes also revere white buffalo.

"Many tribes have their own story of why the white buffalo is so important," Heinert said. "All stories go back to them being very sacred."

Heinert and several members of the Buffalo Field Campaign say they've never heard of a white buffalo being born in Yellowstone, which has wild herds. Park officials had not seen the buffalo yet and could not confirm its birth in the park, and they have no record of a white buffalo being born in the park previously.

Jim Matheson, executive director of the National Bison Association, could not quantify how rare the calf is.

"To my knowledge, no one's ever tracked the occurrence of white buffalo being born throughout history. So I'm not sure how we can make a determination how often it occurs."

Besides herds of the animals on public lands or overseen by conservation groups, about 80 tribes across the U.S. have more than 20,000 bison, a figure that's been growing in recent years.

In Yellowstone and the surrounding area, the killing or removal of large numbers of bison happens almost every winter, under an agreement between federal and Montana agencies that has limited the size of the park's herds to about 5,000 animals. Yellowstone officials last week proposed a slightly larger population of up to 6,000 bison, with a final decision expected next month.

But ranchers in Montana have long opposed increasing the Yellowstone herds or transferring the animals to tribes. Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte has said he would not support any management plan with a population target greater than 3,000 Yellowstone bison.

Heinert sees the calf's birth as a reminder "that we need to live in a good way and treat others with respect."

"I hope that calf is safe and going to live its best life in Yellowstone National Park, exactly where it was designed to be," Heinert said.

Washington state's Makah tribe clears hurdle toward resuming whale hunts

The United States granted the Makah Indian Tribe in Washington state a long-sought waiver Thursday that helps clear the way for its first sanctioned whale hunts since 1999.

The Makah, a tribe of 1,500 people on the northwestern tip of the Olympic Peninsula, is the only Native American tribe with a treaty that specifically mentions a right to hunt whales. But it has faced more than two decades of court challenges, bureaucratic hearings and scientific review as it seeks to resume hunting gray whales.

The decision by NOAA Fisheries grants a waiver under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which otherwise forbids harming marine mammals. It allows the tribe to hunt up to 25 Eastern North Pacific gray whales over 10 years, with a limit of two to three per year. There are roughly 20,000 whales in that population, and the hunts will be timed to avoid harming endangered Western North Pacific gray whales that sometimes visit the area.

Nevertheless, hurdles remain. The tribe must enter into a cooperative agreement with the agency under the Whaling Convention Act, and it must obtain a permit to hunt, a process that involves a monthlong public comment period.

Animal rights advocates, who have long opposed whaling, could also challenge NOAA's decision in court.

Archeological evidence shows that Makah hunters in cedar canoes killed whales for sustenance from time immemorial, a practice that ceased only in the early 20th century after commercial whaling vessels depleted the population.

By 1994, the Eastern Pacific gray whale population had rebounded, and they were removed from the endangered species list. Seeing an opportunity to reclaim its heritage, the tribe announced plans to hunt again.

The Makah trained for months in the ancient ways of whaling and received the blessing of federal officials and the International Whaling Commission. They took to the water in 1998 but didn't succeed until the next year, when they harpooned a gray whale from a hand-carved cedar canoe. A tribal member in a motorized support boat killed it with a high-powered rifle to minimize its suffering.

It was the tribe's first successful hunt in 70 years.

The hunts drew protests from animal rights activists, who sometimes threw smoke bombs at the whalers and sprayed fire extinguishers into their faces. Others veered motorboats between the whales and the tribal canoes to interfere with the hunt. Authorities seized several vessels and made arrests.

After animal rights groups sued, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned federal approval of the tribe's whaling plans. The court found that the tribe needed to obtain a waiver under the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Eleven Alaska Native communities in the Arctic have such a waiver for subsistence hunts, allowing them to kill bowhead whales — even though bowheads are listed as endangered.

The Makah tribe applied for a waiver in 2005. The process repeatedly stalled as new scientific information about the whales and the health of their population was uncovered.

Some of the Makah whalers became so frustrated with the delays that they went on a rogue hunt in 2007, killing a gray whale that got away from them and sank. They were convicted in federal court.

Native American news roundup, June 2-8, 2024

Native American veterans honored at D-Day commemorations in Normandy

World leaders and veterans, including service members from several Native American tribes, gathered in France to commemorate the 80th anniversary of D-Day, the allied landing on the beaches of Normandy that changed the course of World War II.

Charles Norman Shay, a citizen of the federally recognized Penobscot Nation in Maine, was in the first wave that landed on Omaha Beach. A combat medic assigned to the First Infantry Division, Shay was awarded the Silver Star and the French Legion of Honor for his efforts to save wounded soldiers from the rising waters of the English Channel.

Delegations from several Native American tribes were also in Normandy to pay tribute to Shay and to the tens of thousands of Native Americans who served in World War II, including an unknown number of Native Americans who landed at Normandy in 1944.

Shay, who turns 100 later this week, is the last surviving Native American soldier to have fought on D-Day.

Read more:

Ho-Chunk congresswoman: States ‘deprive’ Native Americans of right to vote

June 2 marked 100 years since President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, also known as the Snyder Act, granting full U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States.

Native American lawmakers marked the occasion with a series of editorials.

In a guest essay for Native News Online, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a citizen of the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, argues that Native Americans have always been citizens.

“My people were here long before the Mayflower and the Pilgrims, and before the cow was introduced to North America. We have always been citizens of this continent. Our citizenship runs deep, and in spite of every Indian war, assimilation policy, and outright assault on our land, animals, and ways of life by newcomers, we have persevered,” she wrote.

Representative Sharice Davids, a citizen of the Ho-Chunk Nation in Wisconsin, reminded readers of Indian Country Today that while the 1924 law may have given Native Americans official citizenship, some states still “deprive” them of rights guaranteed to citizens.

“Before this, my ancestors were treated as foreigners in their own land without a voice in the country's most important systems,” Davids wrote. “While the act was a monumental leap in tribal sovereignty, it didn't prevent states from enacting laws that deprived Native communities of their right to vote.”

Davids, Senator Ben Ray Lujan and Representative Tom Cole (Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma) introduced the Native American Voting Rights Act of 2021 (NAVRA), to improve Native Americans’ access to voter registration, polling places and drop boxes.

Leonard Peltier to appeal again for his release

American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier and his supporters will plead his case next week before a parole board for what may be the last time.

Peltier, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota, was convicted in 1977 of killing two FBI agents during a 1975 standoff on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences.

As VOA reported in 2016, the FBI Agents Association insists Peltier is an “unremorseful, cold-blooded killer” who deserves to remain in prison. His defenders say he was framed for a crime he did not commit.

Peltier is nearly 80 and has spent more than half his life in prison. He has always proclaimed his innocence and has twice been denied parole.

Amnesty International USA followed the case for years and recently wrote the U.S. Parole Commission to plead for Peltier’s release on humanitarian grounds.

Parole was abolished for federal convicts in 1987, but Peltier remains eligible because he was convicted before that time.

Read more:

Tribes distinguish between co-managing and co-stewarding federal land

As part of his commitment to allow Native American tribes a say in the use of federal lands and waters, President Joe Biden expanded the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument in Northern California to include a 17.7-kilometer-long (11-mile-long) north-south ridgeline that is sacred to the Patwin people in the region.

Biden’s May 2 proclamation renamed the ridgeline, previously known as Walker Ridge, to Molok Luyuk, or Condor Ridge, in the language of the three federally recognized Patwin tribes: the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation, the Cachil DeHe Band of Wintun Indians of the Colusa Indian Community and the Kletsel Dehe Wintun Nation.

The proclamation also called on Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to explore “co-stewardship” with those tribes. But co-stewardship doesn’t mean co-management. Those are powers only Congress can grant.

“Co-management means decision-making authority,” monument manager Melissa Hovey recently told Grist online magazine. “Co-stewardship means one entity still has the decision-making authority.”

Read more:

Native American news roundup, May 26-June 1, 2024

Senator blocks confirmation of first Native American federal judge

U.S. Senator Steve Daines, a Republican from Montana and member of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, has blocked President Joe Biden’s pick, a Native American woman, to serve as a federal judge in Montana.

Biden in late April tapped Danna Jackson, a tribal attorney for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana, as his choice to serve on the U.S. District Court for the District of Montana.

U.S. Senator Jon Tester, a Democrat from Montana, lauded her nomination.

“Danna Jackson has a proven track record of applying the law with fairness and integrity throughout her legal career, and I have no doubt that she’ll bring these high standards to the federal judiciary and District of Montana,” he said in an April 24 statement.

But Daines complained that Biden had not consulted with him before naming her.

“Federal judges in Montana are crushing our way of life because they legislate from the bench. Montanans want judges who will bring balance to our courts and uphold the Constitution,” he said in a statement.

If confirmed, Danna Jackson would be the first Native American to serve as a federal judge in that state, a lifetime position.

Read more:

Feds to work with South Dakota school district to ensure rights of Native students

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, or OCR, says that the Rapid City Area Schools district in South Dakota has resolved to take action to ensure compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in how it teaches and disciplines students.

In December 2010, the OCR launched several investigations into whether schools in the Rapid City area treated Native American and white students differently in matters of discipline and access to special and advanced learning programs.

The investigation found evidence that Native American students were being disciplined more frequently and more harshly than white students and were discriminated against when it came to accessing advanced learning courses.

The school district has resolved to produce corrective plans, including hiring a “discipline equity supervisor” and advanced learning coordinator and allowing Native American community members a role in revising policies.

Read more:

New report details sexual abuse of Indigenous students in Catholic boarding schools

The Washington Post this week published the results of an investigation into the sexual abuse of Native American children in Catholic-run boarding schools in the Midwest, Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

The investigation revealed that at least 122 priests, nuns and brothers assigned to 22 boarding schools were later accused of sexually abusing more than 1,000 children in their care; most of these cases occurred in the 1950s and 1960s.

In May 2022, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland released the first volume of an investigation into the federal Indian boarding school system designed to assimilate Native children and ultimately take their land.

The initial report found that between 1819 and 1969, the federal Indian boarding school operated 408 federal schools across 37 states and territories.

A highly anticipated second volume was expected to be published in January but has not yet been released. Heidi Todacheene, a senior adviser to Haaland, told New Mexico lawmakers in December that the upcoming report would update the first volume to include names and tribal affiliations of individual students.

In July 2022, Pope Francis traveled to Alberta, Canada, where he apologized for the Catholic Church's role in Canada’s Indigenous residential schools and acknowledged the damaging impact on First Nations’ families and communities.

In a statement following that visit, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition suggested he turn his attention next to the church’s role in the U.S. Indian boarding school system.

‘Mankato hanging hope’ to be repatriated to Minnesota tribe

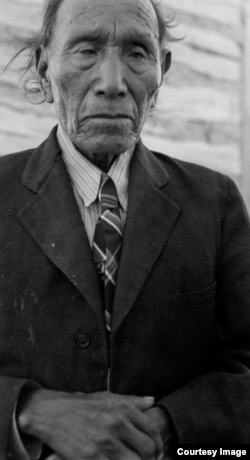

The Minnesota Historical Society has agreed to repatriate the "Mankato Hanging Rope" to the Prairie Island Indian Community, who filed a claim under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

A Minnesota infantry soldier donated the rope to the society in 1869, saying that it had been used to execute Dakota ancestor Wicanhpi Wastedanpi (also known as Chaska).

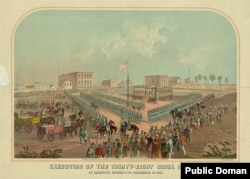

He was one of 303 Dakota men convicted and sentenced to death by a military commission for their roles in the 1862 Dakota War. By law, President Abraham Lincoln was required to review the convictions, and he commuted the sentences of all but 39 men.

One man received a last-minute reprieve, and on December 26, 1862, the remaining 38 men were led to a scaffold in the town of Mankato and hanged in what was the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

It was later learned Wicanhpi Wastedanpi was one of two men hanged by mistake.

Read more:

Native American news roundup, May 12-18, 2024

Navajo president to council: Hurry and approve water rights settlements

Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren has urged the tribal council to quickly approve a pair of proposed water rights settlements.

“The current round of negotiations to settle our claims to the Colorado River in Arizona began in the early 1990s but reach back to the 1960s,” Nygren said in a statement Tuesday. “This is a long time coming, so I look for a unanimous vote from council.”

Navajo Nation council speaker Crystalyne Curley introduced legislation May 11 to address water rights claims in the Rio San Jose Stream System and the Rio Puerco Basin in New Mexico, calling it a “monumental step forward in securing water sovereignty” for Navajo communities and sustaining water resources for “generations to come.”

Under the larger Northeastern Arizona Indian Water Rights Settlement Agreement, which Curley introduced May 12, the Navajo Nation would receive a significant amount of Arizona’s allocation of Colorado River Upper Basin water, a portion of Lower Basin water, all groundwater underneath the Navajo Nation and all surface water reaching the Navajo Nation from the Little Colorado River.

The Navajo Nation covers 70,000 square kilometers (27,000 square miles). About 30% of Navajo families live without running water and must haul it from remote wells in order meet their basic household and livestock needs.

If Congress authorizes the agreement, it will provide up to $5 billion worth of water infrastructure and development for Navajo, Hopi and San Juan Southern Paiute tribes in Arizona.

Read more:

Eight out of nine tribes banish South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem

Two more tribes in South Dakota this week banished Republican Governor Kristi Noem from their reservations over her suggestions that tribal leaders benefit from drug cartel activity.

The Lower Brule Sioux Tribe endorsed a ban on Wednesday, a day after the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe passed a similar resolution. Now, the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe is the only one of nine tribes in South Dakota that has not followed suit.

“We want our children and fellow tribal members & tribal relatives across the State to be seen as equals and treated with respect and dignity like any other ethnicity in our State,” Lower Brule tribal chairman Clyde J. R. Estes posted on Facebook.

The bans follow remarks Noem made during separate town hall meetings in March.

“Their [tribes’] kids don’t have any hope. They don’t have parents who show up and help them,” Noem said, and she suggested that Mexican drug cartels operate on reservations to the benefit of some tribal leaders.

Crow Creek chairman Peter Lengkeek told South Dakota Public Broadcasting Wednesday that no Mexican drug cartels operate on his reservation.

“We have cartel products, like guns and drugs, but they pass over state highways getting to the reservation,” he said.

Tuesday, Noem appointed a former Oglala Sioux Tribe Department of Public Safety chief to serve on the state’s Department of Tribal Relations, alleging he “found himself without a job” after he told the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs about the cartel presence on tribal lands.

Noem’s office did not respond to VOA’s request for comment.

Read more:

Graduating student forced to remove beaded cap, feather

Native Americans protested on social media after officials at a New Mexico high school graduation ceremony confiscated a Lakota student’s beaded cap and feather.

In a video widely shared on social media, two Farmington High School officials are seen taking a cap and feather from Genesis White Bull and replacing it with one that was unadorned.

Navajo Nation first lady Jasmine Blackwater-Nygren expressed support for White Bull and for all students wishing to wear items of cultural significance on graduation day.

“For some graduates, this is the last graduation ceremony they will ever have,” she posted. “Deciding what to wear goes far beyond a simple decision of what color dress or shoes to wear. For Native students, this is a day to proudly wear our traditional regalia [that] reminds us of how far we’ve come as a people.”

Read more:

Colorado town cancels artist’s residency over controversial painting

Hunkpapa Lakota artist Danielle SeeWalker was slated to become the first Native American to serve as Vail, Colorado’s, summer 2024 artist-in-residence.

But that was before SeeWalker posted a painting titled “G is for Genocide” on social media. It shows a near-faceless woman wearing a feather and a keffiyeh, the traditional Bedouin headscarf that has become the symbol for solidarity with Palestinians.

“It is about me expressing the parallels between what is happening to the innocent people in Gaza ... to that of the genocide of Native American populations here in our lands,” SeeWalker wrote in an Instagram post.

A community member saw the post and complained to the city, which abruptly canceled this year’s residency program just weeks before it was slated to begin.

“They called me last week, and the phone call lasted about a minute and a half,” SeeWalker told VOA. “I didn’t get a word in edgewise. If I could have had the opportunity to have a fruitful, engaging conversation about what I stand for as an artist, as an Indigenous woman, I would have appreciated that.”

In a statement on its website, the town of Vail said that while it “embraces her messaging and artwork surrounding Native Americans,” the town does not want to use public funds to support “any position on a polarizing geopolitical issue.”

Read more:

Native American news roundup, May 5-11, 2024

Senators look to improve services for Indigenous elders

U.S. Senators Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) and Tina Smith (D-Minnesota) have introduced legislation to improve federal programs and services for Alaska Native, American Indian, and Native Hawaiian elders and allow them to age in their home communities.

The Enhancing Native Elders’ Longevity, Dignity, Empowerment, and Respect (Native ELDER) Act would set up an advisory committee to improve OAA services to Native American elders, who already face worse health outcomes compared to other senior citizens.

“When meeting with Alaska stakeholders, they identified home modifications to improve accessibility and caregiver support as some of the greatest unmet needs for Alaska Native Elders,” Murkowski said.

Smith said that giving elders the tools to age comfortably and with dignity in their own homes will help keep tribal communities strong.

“I’m proud this bill will help to deliver on that promise,” she added.

Read more:

Feds fail to respond to syphilis crisis among Great Plains tribes

The U.S. Health and Human Services Department had failed to respond to urgent calls from Great Plains tribes about alarming rates of syphilis cases among Native Americans in the region, according to the nonprofit digital newsroom ProPublica.

The statistics are alarming: In 2023, three percent of all Native American babies born in South Dakota were infected, and the syphilis rate among Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains is higher than any recorded rate in the U.S. since 1941, the year doctors discovered the infection could be treated with penicillin.

In February, the Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board called on HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra to declare a state of emergency, to send in Public Health Services officers to help diagnose and treat cases, and to fund tribal efforts to better respond to the crisis.

So far, Becerra has not responded, but an HHS spokesperson told ProPublica that the department has received the request and will “respond directly.”

Read more:

South Dakota governor now banned from five Indian reservations

This week, the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate, or SWO, became the fifth Native American tribe in South Dakota to ban Governor Kristi Noem from Trust Lands of the Lake Traverse Reservation until such time that she issues a formal and public apology.

The resolution, passed Tuesday, says Noem has “made statements and undertaken actions that have been injurious toward the parents of tribal children, thus detracting from the value of their education.”

It also accuses Noem of “undermining the Tribal Council’s efforts to combat the drug epidemic.”

During a town hall meeting on March 13, Noem said she believes tribal leaders are 'personally benefiting' from drug cartels and that tribal children 'don’t have parents who show up and help them.'

To date, five tribes have banned Noem from about 17 percent of land in the state.

Dakota News Now reports that other tribes are considering similar bans.

Read more:

NARF: Indigenous students deserve both recognition and religion

Growing numbers of Native American students are stepping up to assert their rights to wear feathers, leis and other cultural regalia during graduation ceremonies. While many schools across the country allow the practice, some school districts hold out, saying it violates dress codes.

The Native American Rights Fund, or NARF, has developed a pair of flyers to help students and schools navigate the issue. One flyer is designed to help students responsibly advocate for changes in school policy.

A second flyer aims to help school districts understand the cultural and religious significance of wearing eagle feathers.

“The U.S. Constitution’s Free Exercise Clause protects religious practices and recognize[s] the exercise of religion as an unalienable right,” NARF states on its website. “Wearing an eagle feather or regalia to show academic success and religious beliefs should be considered protected practices.”

Read more:

Tribes, advocacy group, fight Montana TikTok ban

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, or CSKT, and the National Congress of American Indians, or NCAI, have joined in the fight against Montana’s 2023 TikTok ban on grounds that it violates tribal sovereignty.

In April 2023, Montana became the first U.S. state to ban TikTok on all personal devices operating inside the state. It cited concerns that TikTok, owned by the Chinese tech firm Bytedance, could use the platform to harvest user data and share it with the Chinese Communist Party.

In November 2023, a federal judge temporarily blocked the ban as a violation of free speech rights. NCAI and the CSKT, along with other free speech and internet freedom advocacy groups, are now urging a federal appeals court to uphold the lower court’s decision.

In an amicus brief filed Tuesday, they argued that the ban infringes on tribal sovereignty including tribes' digital sovereignty.

Read more:

D-Day veteran spreads message of peace ahead of 80th anniversary

On D-Day, Charles Shay was a 19-year-old U.S. Army medic who was ready to give his life — and save as many as he could.

Now 99, he's spreading a message of peace with tireless dedication as he's about to take part in the 80th anniversary commemorations of the landings in Normandy that led to the liberation of France and Europe from Nazi Germany occupation.

"I guess I was prepared to give my life if I had to. Fortunately, I did not have to," Shay said in an interview with The Associated Press.

A Penobscot tribe citizen from Indian Island in the U.S. state of Maine, Shay has been living in France since 2018, not far from the shores of Normandy where many world leaders are expected to come next month. Solemn ceremonies will be honoring the nearly 160,000 troops from Britain, the U.S., Canada and other nations who landed on June 6, 1944.

Nothing could have prepared Shay for what happened that morning on Omaha Beach: bleeding soldiers, body parts and corpses strewn around him, machine-gun fire and shells filling the air.

"I had been given a job, and the way I looked at it, it was up to me to complete my job," he recalled. "I did not have time to worry about my situation of being there and perhaps losing my life. There was no time for this."

Shay was awarded the Silver Star for repeatedly plunging into the sea and carrying critically wounded soldiers to relative safety, saving them from drowning. He also received France's highest award, the Legion of Honor, in 2007.

Still, Shay could not save his good friend, Pvt. Edward Morozewicz. The sad memory remains vivid in his mind as he describes seeing his 22-year-old comrade lying on the beach with a serious stomach wound.

"He had a wound that I could not help him with because I did not have the proper instruments ... He was bleeding to death. And I knew that he was dying. I tried to comfort him. And I tried to do what I could for him, but there was no help," he said. "And while I was treating him, he died in my arms."

"I lost many close friends," he added.

A total of 4,414 Allied troops were killed on D-Day itself, including 2,501 Americans. More than 5,000 were wounded.

Shay survived. At night, exhausted, he eventually fell asleep in a grove above the beach.

"When I woke up in the morning. It was like I was sleeping in a graveyard because there were dead Americans and Germans surrounding me," he recalled. "I stayed there for not very long and I continued on my way."

Shay then pursued his mission in Normandy for several weeks, rescuing those wounded, before heading with American troops to eastern France and Germany, where he was taken prisoner in March 1945 and liberated a few weeks later.

After World War II, Shay reenlisted in the military because the situation of Native Americans in his home state of Maine was too precarious due to poverty and discrimination.

"I tried to cope with the situation of not having enough work or not being able to help support my mother and father. Well, there was just no chance for young American Indian boys to gain proper labor and earn a good job," he said.

Maine would not allow individuals living on Native American reservations to vote until 1954.

Shay continued to witness history — returning to combat as a medic during the Korean War, participating in U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands and later working at the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna, Austria.

For over 60 years, he did not talk about his WWII experience.

But he began attending D-Day commemorations in 2007 and in recent years, he has seized many occasions to give his powerful testimony. A book about his life, "Spirits are guiding" by author Marie-Pascale Legrand, is about to be released this month.

In 2018, he moved from Maine to Bretteville-l'Orgueilleuse, a French small town in the Normandy region to stay at a friend's home.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-21, coming from his nearby home, he was among the few veterans able to attend commemorations. He stood up for all others who could not make the trip amid restrictions.

Shay also used to lead a Native American ritual each year on D-Day, burning sage in homage to those who died. In 2022, he handed over the remembrance task to another Native American, Julia Kelly, a Gulf War veteran from the Crow tribe, who since has performed the ritual in his presence.

The Charles Shay Memorial on Omaha Beach pays tribute to the 175 Native Americans who landed there on D-Day.

Often, Shay expressed his sadness at seeing wars still waging in the world and what he considers the senseless loss of lives.

Shay said he had hoped D-Day would bring global peace. "But it has not, because you see that we go from one war to the next. There will always be wars. People and nations cannot get along with each other."

As US spotlights those missing or dead in Native communities, prosecutors work to solve their cases

It was a frigid winter morning when authorities found a Native American man dead on a remote gravel road in western New Mexico. He was lying on his side, with only one sock on, his clothes gone and his shoes tossed in the snow.

There were trails of blood on both sides of his body and it appeared he had been struck in the head.

Investigators retraced the man's steps, gathering security camera footage that showed him walking near a convenience store miles away in Gallup, an economic hub in an otherwise rural area bordered on one side by the Navajo Nation and Zuni Pueblo on the other.

Court records said the footage and cell phone records showed the victim — a Navajo man identified only as John Doe — was "on a collision course" with the man who would ultimately be accused of killing him.

A grand jury has indicted a man from Zuni Pueblo on a charge of second-degree murder in the Jan. 18 death, and prosecutors say more charges are likely as he is the prime suspect in a series of crimes targeting Native American men in Gallup, Zuni and Albuquerque. Investigators found several wallets, cell phones and clothing belonging to other men when searching his vehicle and two residences.

As people gathered around the nation on Sunday to spotlight the troubling number of disappearances and killings in Indian Country, authorities say the New Mexico case represents the kind of work the U.S. Department of Justice had aspired to when establishing its Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons outreach program last summer.

Special teams of assistant U.S. attorneys and coordinators have been tasked with focusing on MMIP cases. Their goal: Improve communication and coordination across federal, tribal, state and local jurisdictions in hopes of bridging the gaps that have made solving violent crimes in Indian Country a generational challenge.

Some of the new federal prosecutors were participating in MMIP Awareness Day events. From the Arizona state capitol to a cultural center in Albuquerque and the Qualla Boundary in North Carolina, marches, symposiums, art exhibitions and candlelight vigils were planned for May 5, which is the birthday of Hanna Harris, who was only 21 when she was killed on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana in 2013.

It was an emotional day in Albuquerque, where family members and advocates participated in a prayer walk. They chanted: "What do we want? Answers! What do we want? Justice!" There were tears and long embraces as they shared their stories and frustrations. They talked about feeling forgotten and the lack of resources in Native communities.

Geraldine Toya of Jemez Pueblo marched with other family members to bring awareness to the death of her daughter Shawna Toya in 2021. She said she and her husband are artists who make pottery and never dreamed they would end up being investigators in an effort to determine what happened to their daughter.

"Our journey has been rough, but you know what, we're going to make this journey successful for all of our people that are here in this same thing that we're struggling through right now," she said, vowing to support other families through their heartbreak as they seek justice.

Alex Uballez, the U.S. attorney for the District of New Mexico, told The Associated Press on Friday that the outreach program is starting to pay dividends.

"Providing those bridges between those agencies is critical to seeing the patterns that affect all of our communities," Uballez said. "None of our borders that we have drawn prevents the spillover of impacts on communities — across tribal communities, across states, across the nation, across international borders."

Assistant U.S. Attorney Eliot Neal oversees MMIP cases for a region spanning New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Utah and Nevada.

Having law enforcement agencies and attorneys talking to each other can help head off other crimes that are often precursors to deadly violence. The other pieces of the puzzle are building relationships with Native American communities and making the justice system more accessible to the public, Neal said.

Part of Neal's work includes reviewing old cases: time-consuming work that can involve tracking down witnesses and resubmitting evidence for testing.

"We're trying to flip that script a little bit and give those cases the time and attention they deserve," he said, adding that communicating with family members about the process is a critical component for the MMIP attorneys and coordinators.

The DOJ over the past year also has awarded $268 million in grants to tribal justice systems for handling child abuse cases, combating domestic and sexual violence and bolstering victim services.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Bree Black Horse was dressed in red as she was sworn in Thursday during a ceremony in Yakima, Washington. The color is synonymous with raising awareness about the disproportionate number of Indigenous people who have been victims of violence.

She prosecutes MMIP cases in a five-state region across California and the Pacific Northwest to Montana. Her caseload is in the double digits, and she's working with advocacy groups to identify more unresolved cases and open lines of communication with law enforcement.

An enrolled member of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and a lawyer for more than a decade, Black Horse said having 10 assistant U.S. attorneys and coordinators focusing solely on MMIP cases is unprecedented.

"This is an issue that has touched not only my community but my friends and my family," she said. "I see this as a way to help make sure that our future generations, our young people don't experience these same kinds of disparities and this same kind of trauma."

In New Mexico, Uballez acknowledged the federal government moves slowly and credited tribal communities with raising their voices, consistently showing up to protest and putting pressure on politicians to improve public safety in tribal communities.

Still, he and Neal said it will take a paradigm shift to undo the public perception that nothing is being done.

The man charged in the New Mexico case, Labar Tsethlikai, appeared in court Wednesday and pleaded not guilty while standing shackled next to his public defender. A victim advocate from Uballez's office was there, too, sitting with victims' family members.

Tsethlikai's attorney argued that evidence had yet to be presented tying her client to the alleged crimes spelled out in court documents. Assistant U.S. Attorney Matthew McGinley argued that no conditions of release would keep the community safe, pointing to cell phone data and DNA evidence allegedly showing Tsethlikai had preyed on people who were homeless or in need of alcohol so he could satisfy his sexual desires.

Tsethlikai will remain in custody pending trial as authorities continue to investigate. Court documents list at least 10 other victims along with five newly identified potential victims. McGinley said prosecutors wanted to focus on a few of the cases "to get him off the street" and prevent more violence.

Native American News Roundup April 28 - May 4, 2024

Communities to commemorate Indigenous missing and murdered

Sunday, May 5, is Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day in the U.S., a date set aside to raise awareness about an epidemic of violence and violent crimes in Native and Indigenous communities.

Communities across the U.S. are marking the day with gatherings, marches and workshops.

Native and First Nations communities in the U.S. and Canada say authorities often fail to investigate these cases, and the lack of closure inflicts despair on tribal communities.

Under the Biden administration, federal agencies have been ordered to enhance public safety and criminal justice for Native Americans. This includes the establishment of a Missing & Murdered Unit within the Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Justice Services.

Read more:

Thousands of Native American families may lose Internet access

This month, the U.S. Internet affordability program will run out of funds, and unless Congress provides additional plans, more than 23 million low-income families will be forced to pay for more expensive service plans or do without the internet altogether.

Native Americans on rural reservations may be hardest hit, CNN reported this week. About 329,500 tribal households are currently enrolled in the program, with the majority of those concentrated in Oklahoma, Arizona, New Mexico, Alaska and South Dakota.

The White House, the Federal Communications Commissions and digital equity advocacy groups are urging Congress to pass the bipartisan ACP Extension Act, which would allocate an additional $7 billion to keep the program running until the end of the year.

In 2021, Congress passed the $1.2 trillion Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal, which allocated more than $14 billion to help low-income families afford high speed Internet. It has offered eligible households a discount of up to $30 per month toward Internet service and up to $75 per month for households on tribal lands. Households also received one-time discounts on the purchasing of laptops, desktop computers or tablets.

Read more:

Navajo resolve to ban uranium hauling on reservation

Navajo President Buu Nygren on April 29 signed a resolution urging President Joe Biden to halt uranium hauling on Navajo lands.

The legislation, supported by the Navajo Nation Council, underscores the lasting devastation caused by past uranium mining and calls for executive action to prevent further harm to land, water and public health.

"The transportation of uranium ore across Navajo Nation lands represents a disregard for Navajo Nation law, threatens its territorial integrity and is a threat to the sovereignty of the Navajo Nation," the resolution reads. "The need to halt plans to transport uranium across Navajo Nation lands is a pressing public need which requires final action by the Navajo Nation Council."

According to the Navajo Nation's Radioactive and Related Substances Equipment, Vehicles, Persons and Materials Transportation Act of 2012, the transportation of uranium within the Navajo Nation is prohibited. However, a provision in the law exempts the transportation of uranium along state and federal highways that cross the reservation.

"We are unwavering in our stance against uranium," Nygren said Monday. "This legislation is a product of the dedication of our legislative and executive bodies of government. Today, united, we are sending a powerful message to Washington, D.C."

Indigenous students mocked at ND high school prom

A North Dakota high school has apologized after a group of white high school students were caught on video mocking traditional powwow dancing during their annual prom dance on April 20.

A number of Native American students from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe captured videos of the incident at the Flasher High School dance. The mother of one of the Indigenous students posted some of them on Facebook.

"At no time was there any intentional intent to disrespect the Native American culture," Flasher Public School superintendent Jerry Erdahl posted on Facebook. "To the Native American people, we are sincerely apologetic. Now, for us here at Flasher Public School, is the time to educate both students and staff on cultural sensitivity issues that can affect values, morals and beliefs of others."

Read more:

Lakota reaction to SD governor's upcoming memoir

South Dakota Republican Governor Kristi Noem continued to face backlash this week in the wake of revelations that she shot and killed a rambunctious 14-month-old puppy because he was "less than worthless … as a hunting dog." The same day, she also killed a male goat because he smelled "disgusting."

Oliver Semans, a Sicangu Lakota citizen from the Rosebud Reservation, told VOA that people are upset.

"You know, dogs are sacred to the Lakota people. Súŋka wakan, sacred dog. Before the horse, it was the dogs that used to take and carry our teepee poles and other things. And when we got the horses, the horses were called wakan, sacred."

The Guardian newspaper broke the story April 26 after getting an advance copy of a forthcoming book in which Noem described the incident as an example of her willingness to do anything "difficult, messy and ugly."

Noem has defended her actions, characterizing the dog as a "working dog, not a puppy" and saying she chose to protect her family.

Native American News Roundup, April 21-27, 2024

US House committee chair stresses tribal sovereignty

Oklahoma congressman Tom Cole is the first Native American to chair the powerful U.S. House Appropriations Committee, which passes bills to fund the federal government.

In a message to constituents Monday, Cole, a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma said, "It is important to remember that Native Americans are the First Americans. They are sovereign nations who governed themselves long before settlers arrived, and they continue to do so today.

"Through legally binding agreements, such as the federal trust responsibility, the United States is obligated to provide services and federal resources to tribes — a responsibility I have been and will continue to work to ensure is met," Cole wrote.

He also stressed the importance of raising congressional awareness about Native American issues, sovereign rights and the unique challenges facing tribal communities.

Read more:

Native Americans most likely victims of deadly police force

A Lee Enterprises' Public Service Journalism team has published the first of a series of stories from more than a year's research into why Native Americans are more likely than any other racial group to die in the hands of law enforcement.

The opening article focuses on South Dakota, home to nine federally recognized tribes, and cites poor funding for police in tribal communities and a lack of accountability for fatal law enforcement incidents. Their investigation also found that loved ones of Native Americans who die in jail or police shootings "struggle to access even the most basic information about how these deaths occur."

According to figures compiled by the Indigenous-led activist and advocacy group NDN Collective, Native Americans represent 8.2% of the South Dakota population but were victims in 75% of fatal police shootings from 2001 to 2023.

In its 2021 report to Congress, the Interior Department's Bureau of Indian Affairs said that its Public Safety and Justice Programs across Indian Country are funded at just under 13% of total need and that it would take an additional 25,655 new officers to adequately serve Indian Country.

As VOA has previously reported, South Dakota governor Kristi Noem has repeatedly criticized the Biden administration for failing to adequately fund tribal law enforcement.

Inadequate funding of tribal safety and justice programs is not a new problem. In July 2003, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission reported that per capita spending on law enforcement in Native American communities was about 60% of the national average.

Read more:

Navajo Nation to investigate abuse allegations

Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren says he welcomes an independent, fair and transparent investigation into allegations of sexual harassment and sexual assault within the office of the tribal president and vice president.

In a Facebook stream April 16, Vice President Richelle Montoya revealed that she was sexually harassed within the office of the president and vice president during an August 2023 staff meeting.

"I was made to feel that I had no power to leave the room, I was made to feel that what I was trying to accomplish didn't mean anything, that I was less than," she said.

She did not name the individual who harassed her, "for fear of retaliation."

In November 2023, Navajo Times reported that former employees had experienced sexual assault and sexual harassment in the same office.

Indigenous journalists call for greater representation in media

The president of the Indigenous Journalists Association, or IJA, this week called on the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues to better support Indigenous journalism

"Globally, Indigenous communities are ignored, misrepresented, maligned and in many cases dehumanized by media portrayals of our cultures, distinct issues and the challenges we face due to the impacts of colonization," said IJA head Christine Trudeau, a citizen of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation.

Fewer than half of 1% of newsroom employees identify as Indigenous, she said, adding that some of the most prestigious news outlets routinely stereotype — or disregard altogether — tribal nations.

"To fully realize self-determination, we must ensure that our cultures are accurately represented in the coverage of our communities," she said.

See Trudeau's full statement in the video above.

Feds return land to tribe in Illinois

One hundred seventy-five years ago, Shab-eh-nay ("Built Like a Bear"), chief of the Prairie Band Potawatomi in Illinois, returned home from an extended visit to Kansas to find that the U.S. government had illegally auctioned off more than 1,200 acres (485 hectares) of land promised under the Prairie du Chien treaty of 1829.

Late last week, the Interior Department announced it would place 130 acres (52 hectares) of the original Shab-ey-nay Reservation land into trust for the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, which is now the only federally recognized tribal nation in Illinois.

Read more:

North Carolina tribe opens medical cannabis dispensary

The Eastern Band of Cherokee, or EBCI, has opened the first cannabis dispensary in the state of North Carolina. The Great Smoky Cannabis Company opened on April 20, known for decades as the national cannabis holiday "4-20."

Marijuana is still illegal in North Carolina, but because the EBCI is a federally recognized sovereign nation, it can make its own laws. The tribe legalized medical marijuana in 2021 and voted to legalize recreational cannabis in September 2023.

North Carolina residents at least 21 years old can apply for a medical card from the EBCI cannabis control board. They will need to demonstrate they have one of 18 medical conditions that include anxiety, PTSD and cancer.

Read more:

What happened to Native American skull looted by Chicago reporter?

NOTE: This story contains culturally sensitive information that may be distressing for some readers. Caution is advised.

WASHINGTON — In the summer of 1889, a group of cynical Chicago crime reporters organized itself as the Whitechapel Club, taking the name of the London district where serial killer Jack the Ripper found his victims.

They rented rooms in a back-alley saloon, and in keeping with the club’s macabre theme, they decorated the walls with relics of war and crimes: revolvers, knives, hangman’s ropes.

“I suppose the gruesome [sic] connotations of the name led to our practice of collecting relics of the tragedies we were constantly reporting,” member Brand Whitlock recalled in his 1914 memoir, “Forty Years of It.”

John C. Spray, the former superintendent of the county’s mental asylum, donated skulls which Whitechapel member Chrysostom “Tomb” Thompson converted into tobacco jars, drinking cups and shades for gas lamps.

Whitechapel member and Chicago Herald writer Charles Goodyear Seymour was among the correspondents who covered the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre of as many as 300 Miniconjou and Hunkpapa Lakota men, women and children in South Dakota. He returned home with a collection of war relics, including a woman’s ghost shirt — white cotton, embroidered with yellow — and Native American skulls, according to Brand.

Seymour also traveled to the Blackfeet and Piegan reservation in Montana, recounted in a May 12, 1891, article for the Herald titled, “How to Steal a Skull.” Seymour described how he and an Army infantry lieutenant sneaked into a graveyard at night and managed to retrieve two skulls.

“There is not much fun in robbing a graveyard,” he wrote, “even if it is an Indian graveyard.”

'A large collection'

The Whitechapel Club’s reputation helped grow its ghastly collection.

“It became the practice of sheriffs and newspapermen everywhere to send anything of that kind to the Whitechapel Club. The result was that within a few years, it had a large collection of skulls of criminals,” Whitlock would later write.

Among Seymour’s contributions was the skull of an “Unc’papa [Hunkpapa Lakota]” woman, described by Whitechapel member George Frank Lydston as “the wife of one of the leading malcontents in the recent outbreak” at Wounded Knee.

Lydston was a Chicago urologist and professor of criminal anthropology at the Chicago-Kent College of Law. He was also a staunch eugenicist who believed that the shape of people’s skulls indicated intelligence or “undesirable” traits such as criminality and other forms of “degeneracy.” Lydston, who was a member of the Whitechapel Club, used some of the skulls to support his research.

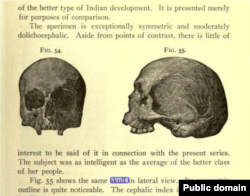

The Wounded Knee skull was among several that Lydston presented in a 1904 book, “The Diseases of Society: The Vice and Crime Problem.”

He concluded little about the Hunkpapa skull, other than that she had an elongated and symmetrical head and was likely “as intelligent as the average of the better class of her people.”