Native Americans

Pacific Northwest tribes battered by climate change but fight to get money meant to help them

Coastal tribes in the Pacific Northwest experience some of the most severe effects of climate change — from rising seas to severe heat — but face an array of bureaucratic barriers to access government funds meant to help them adapt, a report released Monday found.

The tribes are leaders in combating climate change in their region. But a report by the Northwest Climate Resilience Collaborative says as tribes seek money for specific projects to address climate change repercussions, such as relocating a village threatened by rising waters, they often can't provide the matching funds that many grants require or the necessary staff or struggle with stringent application requirements. If they do get funding, it's often a small amount that can only be used for very specific projects when this work is typically much more holistic, the report found.

"Trying to do projects by piecing together grants that all have different requirements and different strings attached, without staff capacity is a challenge," Robert Knapp, environmental planning manager at the Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe in northwest Washington, said in the report.

The collaborative, funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, spent two years holding listening sessions with 13 tribes along the Pacific Coast of Oregon and Washington, the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Puget Sound. The communities face significant challenges from coastal flooding and erosion, rising stream temperatures, declining snowpack, severe heat events and increasing wildfire risk.

In addition to funding challenges, those interviewed also described not having enough staff to adequately respond to climate change as well as sometimes not being able to partner with state and local governments and universities in this work because of their remote locations. They also said it can be hard to explain to people who don’t live in their communities about the impact climate change has on the tribes.

But as they work to restore salmon habitats affected by warming waters or move their homes, funding gaps and complications were key concerns.

A representative from one anonymous tribe in the report said it was not able to hire a grant writer and had to rely on its biology department to navigate the maze of funding applications. Another talked about depending on 15 separate funders just to build a marina.

"This is a time of historic state and federal investment in climate action, and tribal priorities really need to be considered when making decisions around how we're going to be directing this investment," said Meade Krosby, senior author of the report.

"Hopefully this will help to inform how this work is being done, how these funds are being directed, so that they are actually responsive to the barriers that tribes are facing and helping to remove some of those barriers so the tribes can get the good work done."

The Bureau of Indian Affairs did not immediately respond to an email requesting comment.

Most of the tribes included in the report had completed publicly available reports on the impacts of climate change, and some had developed detailed plans for relocation as rising waters threaten buildings, or even entire villages.

The Quinault Indian Nation, in Washington's Olympic Peninsula, has a plan for relocating its largest village. The multimillion-dollar effort has relied on a piecemeal of federal and state grants and the constraints that come with them, Gary Morishima, Quinault's natural resources technical adviser, explained in the report.

Other tribes brought up concerns about competing against other tribal nations for funding when collaboration is such a vital part of responding to climate change. Tribal lands share borders and coastlines, and the impacts of climate change on those lands do not stop at any border, the report pointed out.

Amelia Marchand, citizen of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation and another author of the report, explained that it comes down to the federal government fulfilling its trust responsibility to tribes.

"The treaty is supposed to support and uplift and ensure that what the tribes need for continued existence is maintained," she said. "And that's one of the issues with not having this coordinated federal response because different federal agencies are doing different things."

Millions of dollars have gone to coastal tribes, and the report said much more is needed. It referenced a 2020 Bureau of Indian Affairs report that estimated that tribes in the lower 48 states would need $1.9 billion over the next half-century for infrastructure needs related to climate change.

Amid all the challenges, Pacific Northwest tribes are still leaders in climate adaptation and have plenty to teach other communities, Marchand said.

"Finding ways to make their progress happen for their nations and their communities despite those odds is one of the most inspiring and hopeful resilient stories," she said.

Native American news roundup August 4-10, 2024

Harris win, US could see its first female Native American governor

Kamala Harris’ candidacy for president, alongside Minnesota Governor Tim Walz as her running mate, brings the potential for another historic milestone: If the Harris-Walz ticket succeeds, Minnesota Lieutenant Governor Peggy Flanagan, a member of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe, would become the first Native American woman to serve as a state governor.

Flanagan's career in public service spans decades. She served on the Minneapolis Board of Education from 2005 to 2009. She was also the executive director of the Children’s Defense Fund Minnesota before running unopposed for a seat on the Minnesota House of Representatives in 2015.

She was elected lieutenant governor in 2018 and reelected in 2022. She has been a prominent advocate for Indigenous and abortion rights and helped oversee the creation of the state’s first Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives Office.

Read more:

Tribes outraged over uranium ore hauls

Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs has temporarily stopped the transport of uranium ore across the Navajo Nation, saying tribes were not notified as required.

Energy Fuels had earlier agreed to notify tribal governments two weeks in advance before transporting trucks carrying uranium ore from the Pinyon Plain Mine, near the Grand Canyon, to a uranium mill in Utah.

The Navajo Nation, however, says it never received notice and didn’t find out about the convoy until it had already passed through Navajo lands.

Navajo President Buu Nygren directed his police to stop the transport vehicles on the return trip and escort them off the reservation.

A spokesperson for Energy Fuels said the company had complied with notice requirements, and the company's president said the risks of transporting the unprocessed ore were minimal.

The plan was for an estimated six trucks per day to carry over 22,000 kilograms of ore over three to five years until the mine is exhausted.

The Havasupai Tribe has fears that mining in the area could contaminate the deep groundwater aquifer that supplies its drinking water and is calling on the government to stand by tribes.

Read more:

Colville tribes back out of wolf repatriation deal with Colorado

The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation have backed out of an agreement to provide 15 gray wolves for Colorado’s reintroduction efforts. They say Colorado’s Parks and Wildlife agency failed to conduct “necessary and meaningful consultation with potentially impacted tribes,” in particular, the Southern Ute Tribe.

In January, the Colville tribes agreed to capture and send up to 15 wolves to Colorado.

But the Southern Ute Tribe has long opposed wolf reintroduction due to potential negative impacts on tribal livelihoods, livestock and wildlife, including elk and moose.

The Southern Ute Tribal Council passed a resolution in 2020 stressing the significance of the Brunot Agreement Area, more than 14 million hectares (3.5 million acres) of reservation they ceded to the government in 1873, while retaining hunting rights. That resolution also noted that gray wolves carry hydatid disease, a parasite that could infect domestic animals and humans.

Read more:

California tribe rides to Washington, DC, to seek congressional recognition

Members of a tribe calling itself the Muwekma Ohlone set out Sunday from San Francisco, California, on a three-month cross-country horseback ride to Washington, D.C. There, they hope to persuade lawmakers to grant them federal recognition long denied by the Interior Department.

They say they are descendants of the Verona Band of Alameda County, who have been present in the Bay Area for more than 10,000 years. Chairwoman Charlene Nijmeh says “special interests, money and corrupted politics” have stopped them from being recognized.

The group, then calling itself the “Ohlone/Costanoan Muwekma Tribe,” first petitioned for federal recognition in 1989, claiming direct lineal descendency from the historical Verona Band. This tribe was last acknowledged by the government in 1927.

Bureau of Indian Affairs records show that the agency rejected their petition, saying the tribe had failed to provide evidence that it had operated as a cohesive political group on a "substantially continuous basis" as the Verona Band or as a tribe that evolved from that band.

Federally recognized tribes are acknowledged as sovereign entities and are entitled to receive some federal benefits, services and protections because of their special relationships with the U.S. government.

Tribes may bypass BIA and directly petition Congress for recognition. Between 1975 and 2013, members of Congress introduced 178 bills seeking to extend recognition to 72 Indian nations and recognized 32.

Read more:

Tribes wait to get items back, 6 months after museums shut Native exhibits

Tucked within the expansive Native American halls of the American Museum of Natural History is a diminutive wooden doll that holds a sacred place among the tribes whose territories once included Manhattan.

For more than six months now, the ceremonial Ohtas, or Doll Being, has been hidden from view after the museum and others nationally took dramatic steps to board up or paper over exhibits in response to new federal rules requiring institutions to return sacred or culturally significant items to tribes — or at least to obtain consent to display or study them.

Museum officials are reviewing more than 1,800 items as they work to comply with the requirements while also eyeing a broader overhaul of the more than half-century-old exhibits.

But some tribal leaders remain skeptical, saying museums have not acted swiftly enough. The new rules, after all, were prompted by years of complaints from tribes that hundreds of thousands of items that should have been returned under the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 still remain in museum custody.

"If things move slowly, then address that," said Joe Baker, a Manhattan resident and member of the Delaware Tribe of Indians, descendants of the Lenape peoples European traders encountered more than 400 years ago. "The collections, they're part of our story, part of our family. We need them home. We need them close."

Sean Decatur, the New York museum's president, promised tribes will hear from officials soon. He said staff these past few months have been reexamining the displayed objects in order to begin contacting tribal communities.

Museum officials envision a total overhaul of the closed Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains halls — akin to the five-year, $19 million renovation of its Northwest Coast Hall, completed in 2022 in close collaboration with tribes, Decatur added.

"The ultimate aim is to make sure we're getting the stories right," he said.

Discussions with tribal representatives over the Ohtas began in 2021 and will continue, museum officials said, even though the doll does actually not fall under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act because it is associated with a tribe outside the U.S., the Munsee-Delaware Nation in Ontario, Canada.

The museum also plans to open a small exhibit in the fall incorporating Native American voices and explaining the history of the closed halls, why changes are being made and what the future holds, he said.

Lance Gumbs, vice chairman of the Shinnecock Indian Nation, a federally recognized tribe in New York's Hamptons, said he worries about the loss of representation of local tribes in public institutions, with exhibit closures likely stretching into years.

The American Museum of Natural History, he noted, is one of New York's major tourism draws and also a mainstay for generations of area students learning about the region's tribes.

He suggests museums use replicas made by Native peoples so that sensitive cultural items aren't physically on display.

"I don't think tribes want to have our history written out of museums," Gumbs said. "There's got to be a better way than using artifacts that literally were stolen out of gravesites."

Gordon Yellowman, who heads the department of language and culture for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, said museums should look to create more digital and virtual exhibits.

He said the tribes, in Oklahoma, will be seeking from the New York museum a sketchbook by the Cheyenne warrior Little Finger Nail that contains his drawings and illustrations from battle.

The book, which is in storage and not on display, was plucked from his body after he and other tribe members were killed by U.S. soldiers in Nebraska in 1879.

"These drawings weren't just made because they were beautiful," Yellowman said. "They were made to show the actual history of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people."

Institutions elsewhere are taking other approaches.

In Chicago, the Field Museum has established a Center for Repatriation after covering up several cases in its halls dedicated to ancient America and the peoples of the coastal Northwest and Arctic.

The museum has completed four repatriations to tribes involving around 40 items over the past six months, with at least three more repatriations pending involving additional items. Those repatriations were through efforts that were underway before the new regulations, according to Field Museum spokesperson Bridgette Russell.

At the Cleveland Museum in Ohio, a case displaying artifacts from the Tlingit people in Alaska has been reopened after their leadership gave consent, according to Todd Mesek, the museum's spokesperson. But two other displays remain covered up, with one containing funerary objects from the ancient Southwest to be redone with a different topic and materials.

And at Harvard, the Peabody Museum's North American Indian hall reopened in February after about 15% of its roughly 350 items were removed from displays, university spokesperson Nicole Rura said.

Chuck Hoskin, chief of the Cherokee Nation, said he believes many institutions now understand they can no longer treat Indigenous items as "museum curiosities" from "peoples that no longer exist."

The leader of the tribe in Oklahoma said he visited the Peabody this year after the university reached out about returning hair clippings collected in the early 1930s from hundreds of Indigenous children, including Cherokees, forced to assimilate in the notorious Indian boarding schools.

"The fact that we're in a position to sit down with Harvard and have a really meaningful conversation, that's progress for the country," he said.

As for Baker, he wants the Ohtas returned to its tribe. He said the ceremonial doll should never have been on display, especially arranged as it was among wooden bowls, spoons and other everyday items.

"It has a spirit. It's a living being," Baker said. "So if you think about it being hung on a wall all these years in a static case, suffocating for lack of air, it's just horrific, really."

Nearly 1,000 Native American children died in abusive US schools

At least 973 Native American children died in the U.S. government's abusive boarding school system, according to the results of an investigation released Tuesday by officials who called on the government to apologize for the schools.

The investigation commissioned by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland found marked and unmarked graves at 65 of the more than 400 U.S. boarding schools that were established to forcibly assimilate Native American children into white society. The findings don't specify how each child died, but the causes of death included sickness, accidents and abuse during a 150-year period that ended in 1969, officials said.

The findings follow a series of listening sessions across the United States over the past two years in which dozens of former students recounted the harsh and often degrading treatment they endured while separated from their families.

"The federal government — facilitated by the Department I lead — took deliberate and strategic actions through federal Indian boarding school policies to isolate children from their families, deny them their identities, and steal from them the languages, cultures and connections that are foundational to Native people," Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe in New Mexico and the country's first Native American Cabinet secretary, said in a news release Tuesday.

In an initial report released in 2022, officials estimated that more than 500 children died at the schools. The federal government passed laws and policies in 1819 to support the schools, the last of which were still operating in the 1960s.

The schools gave Native American children English names, put them through military drills and forced them to perform manual labor, such as farming, brickmaking and working on the railroad, officials said.

Former students shared tearful recollections of their experience during listening sessions in Oklahoma, South Dakota, Michigan, Arizona, Alaska and other states. They talked about being punished for speaking their native language, being locked in basements and having their hair cut to stamp out their identities. They were sometimes subjected to solitary confinement, beatings and the withholding of food. Many left the schools with only basic vocational skills that gave them few job prospects.

Donovan Archambault, 85, of the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana, said he was sent away to boarding schools beginning at age 11 and was mistreated, forced to cut his hair and prevented from speaking his native language. He said he drank heavily before turning his life around more than two decades later, and never discussed his school days with his children until he wrote a book about the experience several years ago.

"An apology is needed. They should apologize," Archambault told The Associated Press by phone Tuesday. "But there also needs to be a broader education about what happened to us. To me, it's part of a forgotten history."

The new report doesn't specify who should issue the apology on behalf of the federal government, saying only that it should be issued through "appropriate means and officials to demonstrate that it is made on behalf of the people of the United States and be accompanied by bold and actionable policies."

Interior Department officials also recommended that the government invest in programs that could help Native American communities heal from the traumas caused by boarding schools. That includes money for education, violence prevention and the revitalization of indigenous languages. Spending on those efforts should be on a scale proportional to the money spent on the schools, agency officials said.

The schools, similar institutions and related assimilation programs were funded by more than $23 billion in inflation-adjusted federal spending, officials determined. Religious and private institutions that ran many of the institutions received federal money as partners in the campaign to "civilize" Indigenous students, according to the new report.

By 1926, more than 80% of Indigenous school-age children — some 60,000 children — were attending boarding schools that were run either by the federal government or religious organizations, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

Legislation pending before Congress would establish a Truth and Healing Commission to document and acknowledge past injustices related to boarding schools. The measure is sponsored in the Senate by Democrat Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and backed by Republican Lisa Murkowski of Alaska.

Apache Christ icon controversy sparks debate over Indigenous Catholic faith practices

Anne Marie Brillante never imagined she would have to choose between being Apache and being Catholic.

To her, and many others in the Mescalero Apache tribe in New Mexico who are members of St. Joseph Apache Mission, their Indigenous culture had always been intertwined with faith. Both are sacred.

"Hearing we had to choose, that was a shock," said a tearful Brillante, a member of the mission's parish council.

The focus of this tense, unresolved episode is the 8-foot Apache Christ painting. For this close-knit community, it is a revered icon created by Franciscan friar Robert Lentz in 1989. It depicts Christ as a Mescalero medicine man and has hung behind the church's altar for 35 years under a crucifix as a reminder of the holy union of their culture and faith.

On June 26, the church's then-priest, Peter Chudy Sixtus Simeon-Aguinam, removed the icon and a smaller painting depicting a sacred Indigenous dancer. Also taken were ceramic chalices and baskets given by the Pueblo community for use during the Eucharist.

Brillante said the priest took them away while the region was reeling from wildfires that claimed two lives and burned more than 1,000 homes.

The Diocese of Las Cruces, which oversees the mission, did not respond to several emails, phone calls and an in-person visit by The Associated Press.

Parishioners, shocked to see the blank wall behind the altar when they arrived for Catechism class, initially believed the art objects had been stolen. But Brillante was informed by a diocesan official that the icon's removal occurred under the authority of Bishop Peter Baldacchino and in the presence of a diocesan risk manager.

The diocese has returned the icons and other objects after the community's outrage was covered by various media outlets, and the bishop replaced Simeon-Aguinam with another priest. But Brillante and others say it's insufficient to heal the spiritual abuse they have endured.

Brillante said their former priest opened old wounds with his recent actions, suggesting he sought to cleanse them of their "pagan" ways, and it has derailed the reconciliation process initiated by Pope Francis in 2022. That year, Francis gave a historic apology for the Catholic Church's role in Indigenous residential schools, forcing Native people to assimilate into Christian society, destroying their cultures and separating families.

A spokesperson for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops declined comment on the Mescalero case. But last month, the conference overwhelmingly approved a pastoral framework for Indigenous ministry, which pointed to a "false choice" many Indigenous Catholics are faced with — to be Indigenous or Catholic:

"We assure you, as the Catholic bishops of the United States, that you do not have to be one or the other. You are both."

Several of the mission's former priests understood this, but Brillante believes Simeon-Aguinam's recent demand to make that "false choice" violated the bishops' new guidelines.

Larry Gosselin, a Franciscan who served St. Joseph from 1984 to 1996 and again from 2001 to 2003, said he sought the approval of 15 Mescalero leaders before Lentz began the painting that took three months to complete.

"He poured all of himself into that painting," said Gosselin, explaining that Lentz sprinkled gold dust on himself and skipped showering, using his body oils to adhere the gold to the canvas. Then he gave the painting to the humble church.

Albert Braun, the priest who helped construct the church building in the 1920s, respected Mescalero Apache traditions in his ministry and was so beloved that he is buried inside the church, near the altar.

Church elders Glenda and Larry Brusuelas said to right this wrong and to repair this damage, the bishop must issue a public apology.

"You don't call or send a letter," Larry Brusuelas said. "You face the people you have offended and offer some guarantee that this is not going to happen again. That's the Apache way."

While Bishop Baldacchino held a two-hour meeting with the parish council in Mescalero after the items were returned, Brillante said he seemed more concerned about the icon being "hastily" reinstalled rather than acknowledging the harm or offering an apology.

Still, some are hopeful. Parish council member Pamela Cordova said she views the bishop appointing a new priest who was more familiar with the Apache community as a positive step.

"We need to give the bishop a chance to prove himself and let us know he is sincere and wants to make things right," she said.

The concept of "inculturation," the notion of people expressing their faith through their culture, has been encouraged by the Catholic Church since the Second Vatican Council in the early 1960s, said Chris Vecsey, professor of religion and Native American studies at Colgate University in Hamilton, New York.

"It's rather shocking to see a priest who has been assigned a parish with Native people acting in such a disrespectful way in 2024," he said. "But it does reflect a long history of concern that blending these symbols might weaken, threaten or pollute the purity of the faith."

Deacon Steven Morello, the Archdiocese of Detroit's missionary to the American Indians, said the goal of the U.S. bishops' new framework is to correct the ills of the past. He said Indigenous spirituality and Catholic faith have much in common, such as the burning of sage in Native American ceremonies and incense in a Catholic church.

"Both are meant to cleanse the heart and mind of all distractions," he said. "The smoke goes up to God."

Morello said Pope Francis' encyclical on caring for the Earth and the environment titled "Laudato Si" addresses the sacredness of all creation — a core principle Indigenous people have lived by for millennia.

"There is no conflict, only commonality, between Indigenous and Catholic spirituality," he said.

There are over 340 Native American parishes in the United States and many use Indigenous symbols and sacred objects in church. In every corner of the Mescalero church, Apache motifs seamlessly blend in with Catholic imagery.

The Apache Christ painting hangs as the focal point of the century-old Romanesque church whose rock walls soar as high as 90 feet. Artwork of teepees adorns the lectern. A mural at the altar shows the Last Supper with Christ and his apostles depicted as Apache men. Tall crowns worn by mountain dancers known as "gahe" in Apache, hang over small paintings showing Christ's crucifixion and resurrection.

For parishioner Sarah Kazhe, the Apache Christ painting conveys how Jesus appears to the people of Mescalero.

"Jesus meets you where you are and he appears to us in a way we understand," she said. "Living my Apache way of life is no different than attending church. ... The mindless, thoughtless act of removing a sacred icon sent a message that we didn't matter."

Parishioners believe the Creator in Apache lore is the same as their Christian God. On a recent Saturday night, community members gathered to bless two girls who had come of age. Kazhe and Donalyn Torres, one of the church elders who authorized Lentz to paint the Apache Christ, sat in lawn chairs with more than 100 others, watching crown dancers bring blessings on them.

Under a half-moon, the men wore body paint and tall crowns, dancing to drumbeats and song around a large fire. The women, including the two girls donning buckskin and jewelry, formed the outer circle, moving their feet in a quick, shuffling motion.

In the morning, many from the group attended Mass at their church, the Apache Christ restored to its place of honor.

The painting shows Christ as a Mescalero holy man, standing on the sacred Sierra Blanca, greeting the sun. A sun symbol is painted on his left palm; he holds a deer hoof rattle in his right hand. The inscription at the bottom is Apache for "giver of life," one of their names for the Creator. Greek letters in the upper corners are abbreviations for "Jesus Christ."

Gosselin, the mission's former priest, said he was struck by the level of detail Lentz captured in that painting, particularly the eyes — which focus on a distance just as Apache people would when talking about spirituality. He believes the painting was "divinely inspired" because the people who received it feel a holy connection.

"This has resonated in the spirit and their hearts," he said. "Now, 35 years later, the Apache people are fighting for it."

Native American news roundup, July 21-27, 2024

Pentagon to review whether soldiers deserved honors for actions in Wounded Knee Massacre

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has ordered a panel to review Medals of Honor (MOH) awarded to 20 soldiers for the actions during what the directive calls the “engagement at Wounded Knee Creek” in December 1890 in which U.S. soldiers killed approximately 350 to 375 Lakota men, women, and children.

As the country's highest military honor, the MOH is awarded for gallantry beyond the call of duty.

Experts will assess each awardee's actions to determine whether their actions violated MOH standards, such as “intentionally directing an attack against a non-combatant or an individual who has surrendered in good faith, murder or rape of a prisoner, or engaging in any other act demonstrating immorality.”

The review's findings and recommendations are expected by mid-October.

Read more:

Native Americans speak out against Trump pick for VP

Some Native Americans are voicing concerns about Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump’s pick for a running mate, J.D. Vance, believing him to be anti-Indigenous.

When President Joe Biden designated October 11, 2021, as Indigenous People’s Day, Vance took to the social media platform X (formerly Twitter) to denounce it as a "fake holiday created to sow division.”

Vance also spoke out against the U.S. Forest Service’s plan to rename Ohio’s Wayne National Forest, which was named after 18th Century general Anthony Wayne, who spent much of his military career fighting and divesting Native Americans of their lands.

“He fought wars and won peace for our government, the government you now serve, and hewed Ohio out of rugged wilderness and occupied enemy territory,” Vance wrote in an August 23 letter to the National Forest Service. [[ https://www.vance.senate.gov/press-releases/senator-vance-opposes-plan-to-rename-wayne-national-forest/ ]]

Native Americans also cite pieces of legislation Vance has introduced that they say would undermine tribal sovereignty.

Read more:

Native Americans: Deb Haaland would be a good pick for Harris running mate

As for the Democratic Party vice presidential nomination, now that Vice President Kamala Harris is the likely presidential candidate, some Native Americans think she should choose Interior Secretary Deb Haaland as her running mate.

They point to her achievements running the Department of the Interior (DOI), which manages public lands and minerals, national parks and wildlife refuges and works to uphold Federal trust obligations to Native Americans.

She set up a Missing and Murdered Unit inside DOI’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, which collaborates with law enforcement agencies to help solve missing or unsolved homicide cases.

She launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to investigate Indian boarding schools and account for students who died in the system.

She has also negotiated scores of public land co-stewardship agreements with tribes across the United States.

Read more:

Southwestern tribal leaders to Congress: Act now on water rights bills

Leaders and representatives from Colorado Plateau tribes were in Washington this week, urging Congress to act quickly on water rights settlement acts.

Lawmakers from both parties have introduced legislation in Congress after the Navajo, Hopi Tribe and Southern San Juan Paiute tribes signed off on a historic water rights settlement for waters in the upper and lower basins of the Colorado River, the Little Colorado River basin, the Gila River Basin and claims to groundwater in several aquifers.

Testifying before the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Water, Wildlife, and Fisheries, they highlighted the need for access to water and better water infrastructure.

“Roughly a third of all Navajo households lack running water, including the home I grew up in,” Navajo Nation president Buu Nygren told lawmakers. “Thousands of our people continue to haul water, thirty miles round trip to meet their daily water demands.”

The bill would fund essential water development and delivery projects' acquisition, construction, and maintenance. One of the key components of this initiative is a distribution pipeline projected to cost approximately $1.75 billion. That project would improve water delivery and ensure that tribes gain reliable access to this vital resource, which has long been a concern in areas dependent on the Colorado River.

Specifically, the bill would allow the three tribes to secure over 56,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water each year. To put this into perspective, an acre-foot of water can sustain an average American household for an entire year.

Read more:

Oklahoma tribes outraged by Atlanta Braves ‘tribe night’ celebrations

A group of prominent Oklahoma-based tribal officials is demanding an apology from the Atlanta Braves baseball team for celebrating "Georgia Tribe Night" at its stadium.

During that June 29 event, the Braves hosted representatives from three state- but not federally recognized tribes and members of a state council on American Indian concerns.

Attending a quarterly meeting in Tulsa earlier this month, leaders of the Inter-Tribal Council of the Five Tribes passed a resolution calling for the Braves to apologize and engage in meaningful consultations with federally recognized tribes.

The Inter-Tribal Council comprises leaders from the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole nations, who were driven out of Georgia in the 19th Century and marched along the so-called “Trail of Tears” to what is today Oklahoma.

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr., called event organizers offensive and tone-deaf, noting the Braves’ history of problematic depictions of Native American culture, including the controversial "tomahawk chop" gesture, in which spectators hack at the air and sing a “war chant” rooted in a 1950s children’s cartoon show that stereotyped Indians.

“The Atlanta Braves corporation may consider meaningful consultations with actual Indian tribes instead of trotting representatives of fraudulent organizations posting as tribes as a PR stunt, Hoskin said in a June 30 statement. “This piles insult on top of insult.”

Read more:

US promises $240 million to improve fish hatcheries, protect tribal rights

The U.S. government will invest $240 million in salmon and steelhead hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest to boost declining fish populations and support the treaty-protected fishing rights of Native American tribes, officials announced Thursday.

The departments of Commerce and the Interior said there will be an initial $54 million for hatchery maintenance and modernization made available to 27 tribes in the region, which includes Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Alaska.

The hatcheries "produce the salmon that tribes need to live," said Jennifer Quan, the regional administrator for NOAA Fisheries West Coast Region. "We are talking about food for the tribes and supporting their culture and their spirituality."

Some of the facilities are on the brink of failure, Quan said, with a backlog of deferred maintenance that has a cost estimated at more than $1 billion.

"For instance, the roof of the Makah Tribe's Stony Creek facility is literally a tarp. The Lummi Nation Skookum Hatchery is the only hatchery that raises spring Chinook salmon native to the recovery of our Puget Sound Chinook Salmon," and it is falling down, Quan said.

Lisa Wilson, secretary of the Lummi Indian Business Council, said salmon are as important as the air they breathe, their health and their way of life. She thanked everyone involved in securing "this historic funding."

"Hatchery fish are Treaty fish and play a vital role in the survival of our natural-origin populations while also providing salmon for our subsistence and ceremonies," she said in a statement. "If it weren't for the hatcheries and the Tribes, nobody would be fishing."

The Columbia River Basin was once the world's greatest salmon-producing river system, with at least 16 stocks of salmon and steelhead. Today, four are extinct and seven are listed under the Endangered Species Act. Salmon are a key part of the ecosystem, and another endangered Northwest species, a population of killer whales, depend on Chinook salmon for food.

Salmon are born in rivers and migrate long distances downstream to the ocean, where they spend most of their adult lives. They then make the difficult trip back upstream to their birthplace to spawn and die.

Columbia Basin dams have played a major part in devastating the wild fish runs, cutting off access to upstream habitat, slowing the water and sometimes allowing it to warm to temperatures that are fatal for fish.

For decades, state, federal and tribal governments have tried to supplement declining fish populations by building hatcheries to breed and hatch salmon that are later released into the wild. But multiple studies have shown that hatchery programs frequently have negative impacts on wild fish, in part by reducing genetic diversity and by increasing competition for food.

Quan acknowledged the hatcheries "come with risks" but said they can be managed to produce additional fish for harvest and even to help restore populations while minimizing risks to wild fish.

"Hatcheries have been around for a long time, and we've seen the damage that they can do," Quan said.

Still the programs have gone through a course correction in recent years, following genetic management plans and the principles established by scientific review groups, she said. "We are in a different place now."

It will take habitat restoration, improved water quality, adjustments to harvest and other steps if salmon are going to recover, but so far society has not been willing to make the needed changes for that to happen, she said. Add in the impacts of climate change, and the calculus of bad and good hatchery impacts changes further.

"We need to start having a conversation about hatcheries and how they are going to be an important adaptation tool for us moving forward," Quan said.

Greg Ruggerone, a salmon research scientist with Natural Resources Consultants Inc. in Seattle, said the key is to determine how to better harvest hatchery salmon from rivers without harming the wild salmon that are making the same trek to spawning grounds. Robust harvests of hatchery fish will help ensure that the federal government is meeting its treaty obligations to the tribes, while reducing competition for wild fish, Ruggerone said.

"A big purpose of the hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest is to provide for harvest — especially harvest for the tribes — so there is a big opportunity if we can figure out how to harvest without harming wild salmon," Ruggerone said.

Every hatchery in the Columbia River basin was built to mitigate the effects of the hydropower dams built in the region, said Becky Johnson, the production division director for the Nez Perce Tribe's Department of Fisheries Resource Management.

Most were built in the 1960s, 1970s or earlier, she said.

"I'm super excited about this opportunity. Tribal and non-tribal people benefit from them — more salmon coming back to the basin means more salmon for everyone," Johnson said. "It's critical that we have fish and that the tribal people have food. Tribal members will tell you they're fighting hard to continue to hang on to fish, and they're never going to stop that fight."

Native Americans in Upper Midwest protect their drumming tradition

At summertime social powwows and spiritual ceremonies throughout the Upper Midwest, Native Americans are gathering around singers seated at big, resonant drums to dance, celebrate and connect with their ancestral culture.

"I grew up singing my entire life, and I was always taught that dewe'igan is the heartbeat of our people," said Jakob Wilson, 19, using the Ojibwe term for drum that's rooted in the words for heart and sound. "The absolute power and feeling that comes off of the drum and the singers around it is incredible."

Wilson has led the drum group at Hinckley-Finlayson High School. In 2023, Wilson's senior year, they were invited to drum and sing at graduation. But this year, when his younger sister Kaiya graduated, the school board barred them from performing at the ceremony, creating dismay across Native communities far beyond this tiny town where cornfields give way to northern Minnesota's birch and fir forests.

"It kind of shuts us down, makes us step back instead of going forward. It was hurtful," said Lesley Shabaiash. She was participating in the weekly drum and dance session at the Minneapolis American Indian Center a few weeks after attending protests in Hinckley.

"Hopefully this incident doesn't stop us from doing our spiritual things," added the mother of four, who grew up in the Twin Cities but identifies with the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, whose tribal lands abut Hinckley.

In written statements, the school district's superintendent said the decision to ban "all extracurricular groups" from the ceremony, while making other times and places for performance available, was intended to prevent disruptions and avoid "legal risk if members of the community feel the District is endorsing a religious group as part of the graduation ceremony."

But many Native families felt the ban showed how little their culture and spirituality is understood. It also brought back traumatic memories of their being forcibly suppressed, not only at boarding schools like the one the Wilsons' grandmother attended, but more generally from public spaces.

It was not until the late 1970s that the American Indian Religious Freedom Act directed government agencies to make policy changes "to protect and preserve Native American religious cultural rights and practices."

"We had our language, culture and way of life taken away," said Memegwesi Sutherland, who went to high school in Hinckley and teaches the Ojibwe language at the Minneapolis American Indian Center.

The Center's weekly drum and dance sessions help those who "may feel lost inside" without connections to ancestral ways of life find their way back, said Tony Frank, a drum instructor.

"Singing is a door opener to everything else we do," said Frank, who has been a singer for nearly three decades. "The reason we sing is from our heart. Our connection to the drum and songs is all spiritual. You give 100 percent, so the community can feel a piece of us."

In drum circles like those in Minneapolis, where many Natives are Ojibwe and Lakota, there is a lead singer, who starts each song before passing on the beat and verse to others seated at the drum, which is made of wood and animal hide (usually deer or steer).

A drum keeper or carrier cares for the drum, often revered as having its own spirit and considered like a relative and not like personal property. Keepers and singers are usually male; according to one tradition, that's because women can already connect to a second heartbeat when pregnant.

These lifelong positions are often passed down in families. Similarly, traditional lyrics or melodies are learned from older generations, while others are gifted in dreams to medicine men, several singers said. Some songs have no words, only vocables meant to convey feelings or emulate nature.

Songs and drums at the center of social events like powwows are different from those that are crucial instruments in spiritual ceremonies, for example for healing, and that often contain invocations to the Creator, said Anton Treuer, an Ojibwe language and culture professor at Bemidji State University.

Meant to mark the beginning of a new journey in life, the "traveling song" that the drum group wanted to sing at the Hinckley graduation includes the verse "when you no longer can walk, that is when I will carry you," said Jakob Wilson.

That's why it was meant for the entire graduating class of about 70 students, not only the 21 Native seniors, added Kaiya Wilson, who trained as a back-up singer – and why relegating it to just another extracurricular activity hurt so deeply.

"This isn't just for fun, this is our culture," said Tim Taggart, who works at the Meshakwad Community Center – named after a local drum carrier born in the early 20th century – and helped organize the packed powwow held in the school's parking lot after graduation. "To just be culturally accepted, right? That's all everybody wants, just to be accepted."

The school had taken good steps in recent years, like founding the Native American Student Association, and many in the broader Hinckley community turned out to support Native students. So Taggart is optimistic that after this painful setback, bridges will be rebuilt.

And the drum, with all that it signifies about community and a connected way of life, will be brought back.

"Nothing can function without that heartbeat," said Taggart, whose earliest memory of the drum is being held as a toddler at a ceremony. "It's not just hearing the drums, but you're feeling it throughout your entire body, and that just connects you more with the spirit connection, more with God."

As dancers – from toddlers to adults in traditional shawls – circled the floor to the drum's beat in the Minneapolis center's gym, Cheryl Secola, program director for its Culture Language Arts Network, said it was heartwarming to see families bring children week after week, building connections even if they might not have enough resources to travel to the reservations.

On reservations too, many youths aren't being raised in cultural ways like singing, said Isabella Stensrud-Eubanks, 16, a junior and back-up singer on the Hinckley high school drum group.

"It's sad to say, but our culture is slowly dying out," she said, adding that several elders reached out to her and the Wilsons after the graduation controversy to teach them more, so the youth can themselves one day teach their traditions.

Mark Erickson was already about 20 when he went back to Red Lake, his father's band in northern Minnesota, to learn his people's songs.

"It's taken me a lifetime to learn and speak the language, and a lifetime to learn the songs," said Erickson, who only in his late 60s was awarded the distinction of culture carrier for Anishinaabe songs, a term for Ojibwe and other Indigenous groups in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States.

Believing that songs and drums are gifts from the Creator, he has been going to drum and dance sessions at the Minneapolis Center for more than a decade to share them, and the notions of honor and respect they carry.

"When you're out there dancing, you tend to forget your day-to-day struggles and get some relief, some joy and happiness," Erickson said.

Native American news roundup July 14-20, 2024

Native Americans discuss impact of a second Trump term on tribal communities

Native Americans were noticeably absent from the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, this week. The exception was James Crawford, chairman of the Forest County Potawatomi Community in that state, who opened Day Two of the convention with a speech in which he reminded the audience that events were taking place in lands that were part of the original Potawatomi homelands.

“Our ancestors occupied these lands for hundreds of years, fishing area, rivers and lakes, hunting the land, tapping maple tree groves for sugar and harvesting crops and fields each fall,” Crawford said.

In keeping with Tuesday evening’s theme, “Make America Safe Again,” Crawford addressed threats to Native American safety.

“The growing use and abuse of illegal drugs are claiming countless lives on reservations across this country,” he said, “and Native American women and girls continue to be exploited, trafficked and subjected to violence at reprehensible levels.”

While he did not expressly endorse the Republican ticket, Crawford said he looked forward to working with Republicans to achieve a safe America.

Watch Crawford’s speech below:

Native media’s take on the convention

“Native American Calling,” a radio talk show heard across dozens of public, community and tribal radio stations in the United States and Canada, broadcast live from the event all week, bringing together prominent Native American journalists and business leaders to discuss what a second Donald Trump term might mean for tribal communities.

“Quite clearly, the Republican platform has no mention of Native Americans,” Native News Online editor Levi Rickert noted.

The official platform calls for changes in some federal policies that could impact Native Americans, such as cutting federal funding for any schools pushing “critical race theory (CRT),” an academic concept that racism is built into U.S. legal and government systems, and other “inappropriate racial, sexual or political content.”

The anti-CRT movement has put pressure on many school districts to leave Native American history out of the classroom.

Native American Calling guest panelist Shaun Griswold (Laguna/Zuni/Jemez), editor of Source New Mexico, drew Representative Lauren Boebert into an impromptu interview at the convention in which she stated her desire to head the Interior Department, which manages more than 70% of all federal public lands.

“Public lands are something that are very dear to me,” she said. “ ... and I absolutely care for their [tribal] sovereignty and their prosperity, and that the state and local governments and the federal government is not infringing on your sovereign right."

That said, Boebert said she opposes land grabs by the federal government, such as Joe Biden’s expansion of the Bears Ear National Monument, land sacred to several tribes. See interview, below:

Back to square one

VOA reached out to Shannon O’Loughlin (Choctaw), CEO of the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA). She said the last time she saw a Republican platform address Indian Country was in 2016 during Donald Trump's first campaign.

That platform noted that the federal government has not honored its government-to-government relationship with and trust responsibility for tribes.

“It was something that I don't think the Trump administration really ever adopted,” she said.

She expressed concern over Trump’s plans to overhaul civil service by firing thousands of federal employees and replacing them with those loyal to him and the Republican Party.

“This [election cycle] isn't just about presidents,” O’Loughlin said. “It's also about the people who have been working on Native issues within the agencies, sometimes for decades.”

As mandated by the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the Interior Department gives preference to Native Americans when hiring for Bureau of Indian Affairs or Indian Health Service jobs.

If these people were to be fired, O’Loughlin worries they would be replaced with people who “have no clue about the basis of federal Indian law, policy and the government-to-government relationship.”

And that would bring groups like the AAIA back to square one.

“It's difficult enough for Native peoples. With every single turnover in the administration and Congress, we have the burden of educating all newly appointed or elected officials,” she said. “We are worried that could change how new Interior Department employees would interpret and oversee many of the statutes under U.S. code.”

Killer of 2 Alaska Native women sentenced to 226 years

A judge in Anchorage, Alaska, this week sentenced a convicted murderer to 226 years in prison for the torture and murder of two Alaska Native women.

Brian Smith was convicted in February of 14 counts, including two counts of first-degree murder, second-degree sexual assault, tampering with physical evidence and misconduct involving a corpse.

As VOA reported in 2019, the victims were Kathleen Jo Henry from the Yupik village of Eek in southwestern Alaska, and Veronica Abouchuk, also Yupik, from the western Alaska village of Stebbins.

The case came to light after Anchorage Police Department homicide detectives were alerted by a woman who found a memory card on the ground labeled “Homicide at midtown Marriott.” The videos revealed that Smith had tortured an unknown woman before killing her, disposing of her body and attempting to hide the evidence.

Read more:

Native American news roundup, July 7-13, 2024

Arizona congressional delegation introduces $5 billion tribal water rights legislation

Arizona's congressional delegation Monday introduced a new bill, The Northeastern Arizona Indian Water Rights Settlement Act of 2024, which would ratify a $5 billion water rights settlement with three Native American nations in the southwestern U.S.

This settlement, the largest of its kind proposed by Congress, seeks to resolve a decadeslong dispute involving the Navajo Nation, the Hopi and the San Juan Southern Paiute tribes.

The agreement, approved by the tribes in May, guarantees them over 56,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water and specific groundwater rights. It also establishes a homeland for the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe.

Funds from the legislation will be used to develop and maintain water infrastructure, including a $1.75 billion pipeline.

“Ratifying this settlement honors our commitment to the tribes and helps secure our state’s water future, and we’ll work together as Republicans and Democrats to get it done,” Democratic Senator Mark Kelly said in a statement on his website.

San Juan Southern Paiute tribal President Robbin Preston Jr. said the bill, if passed, would change tribe members’ lives.

“With reliable electricity, water and housing, our people will have opportunities that have never been available to us before,” he said in a statement. “This legislation is more than a settlement of water rights; it is the establishment of an exclusive reservation for a tribe that will no longer be forced to live like strangers in our own land.”

Read more:

Tribes, feds plan future of Bears Ears National Monument

Five Native American tribes and the federal government are collaboratively reviewing over 20,000 public comments on the future management of the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah. The public comment period, which ended on June 11, showed wide support for incorporating Traditional Indigenous Knowledge in managing the monument.

The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, comprising the Zuni Pueblo, Navajo Nation, Hopi Tribe, Ute Mountain Tribe and Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray, is working with the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management to finalize a co-management plan. This plan, the first of its kind, integrates tribal ancestral history, land conservation and traditional education.

Bears Ears is the most significant archaeological area in the U.S., containing more than 100,000 cultural and archaeological sites.

President Joe Biden restored the Bears Ears monument in October 2021 after the Trump administration significantly reduced its size. In 2023, a federal judge dismissed an attempt by Arizona lawmakers to reverse Biden’s decision. The monument’s designation aims to protect it from future uranium mining and follows the National Park Service's commitment to greater tribal involvement in federal land decisions.

Read more:

Feds expand support for tribal home-visiting programs

The U.S. Administration for Children and Families (ACF), an arm of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, has awarded six tribal communities $3 million to expand home-visiting programs for families with young children, part of a larger $30 million investment in the Tribal Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting program.

This funding aims to develop and strengthen tribes’ ability to support and promote the health and well-being of expectant families and families with young children, and prevent children’s placement in foster care.

“We are very excited about this new round of grant recipients, who will develop their programs in collaboration with their communities reflecting their cultures and representing the vision, priorities and hopes they have for future generations,” ACF Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary Jeff Hild said in a statement. “As Tribal home visiting continues to expand, we look forward to engaging with grant recipients and honoring tribal sovereignty as they continue in their journey to provide essential services for young American Indian and Alaska Native children and their families.”

Read more:

Abenaki leaders dispute the legitimacy of unrecognized New Hampshire tribe

The Abenaki community in Quebec has long denounced self-styled Abenaki tribes in Vermont and New Hampshire who operate on claims of Abenaki heritage.

Most recently, a nonprofit called the Ko’asek Traditional Band of the Sovereign Abenaki Nation (KTBSAN) announced plans to build a cultural center in the small New Hampshire city of Claremont on land gifted to them in 2020. In 2023, the city granted their zoning request.

But the KTBSAN is not state or federally recognized, and the Odanak (Abenaki) First Nation in Canada says the New Hampshire group is fake and has no right to speak to Abenaki history and culture.

Historically, Western Abenaki homelands stretched from southeastern Quebec into present-day Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine and north-central Massachusetts. Missionized by French Jesuits in the 17th century, the Abenaki allied themselves with the French in a series of struggles with England over trade. Later, Many Abenaki withdrew to Canada, eventually settling in Saint-François-du-Lac, Quebec.

KTBSAN chief Paul J. Bunnell, a genealogist originally from Massachusetts, told New Hampshire Public Radio that it wasn’t until late in life that he discovered his Abenaki ancestry, information “which we were never told we even had, because it was a taboo subject in most families because we were driven underground because of persecutions.”

Read more:

North Dakota tribe goes back to its roots with a massive greenhouse operation

A Native American tribe in North Dakota will soon grow lettuce in a giant greenhouse complex that when fully completed will be among the country's largest, enabling the tribe to grow much of its own food decades after a federal dam flooded the land where they had cultivated corn, beans and other crops for millennia.

Work is ongoing on the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation's 1.3-hectare greenhouse that will make up most of the Native Green Grow operation's initial phase. However, enough of the structure will be completed this summer to start growing leafy greens and other crops such as tomatoes and strawberries.

"We're the first farmers of this land," Tribal Chairman Mark Fox said. "We once were part of an Aboriginal trade center for thousands and thousands of years because we grew crops — corn, beans, squash, watermelons — all these things at massive levels, so all the tribes depended on us greatly as part of the Aboriginal trade system."

The tribe will spend roughly $76 million on the initial phase, which also will include a warehouse and other facilities near the tiny town of Parshall. It plans to add to the growing space in the coming years, eventually totaling about 5.9 hectares, which officials say would make it one of the world's largest facilities of its type.

The tribe's fertile land along the Missouri River was inundated in the mid-1950s when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the Garrison Dam, which created Lake Sakakawea.

Getting fresh produce has long been a challenge in the area of western North Dakota where the tribe is based, on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. The rolling, rugged landscape — split by Lake Sakakawea — is a long drive from the state's biggest cities, Bismarck and Fargo.

That isolation makes the greenhouses all the more important, as they will enable the tribe to provide food to the roughly 8,300 people on the Fort Berthold reservation and to reservations elsewhere. The tribe also hopes to stock food banks that serve isolated and impoverished areas in the region, and plans to export its produce.

Initially, the MHA Nation expects to grow nearly 907,000 kilograms of food a year and for that to eventually increase to 5.4 million to 6.4 million kilograms annually. Fox said the operation's first phase will create 30 to 35 jobs.

The effort coincides with a national move to increase food sovereignty among tribes.

Supply chain disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic led tribes nationwide to use federal coronavirus aid to invest in food systems, including underground greenhouses in South Dakota to feed the local community, said Heather Dawn Thompson, director of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Office of Tribal Relations. In Oklahoma, multiple tribes are running or building their own meat processing plant, she said.

The USDA promotes its Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiative, which "really challenges us to think about food and the way we do business at USDA from an Indigenous, tribal lens," Thompson said. Examples include Indigenous seed hubs, foraging videos and guides, cooking videos and a meat processing program for Indigenous animals.

"We have always been a very independent, sovereign people that have been able to hunt, gather, grow and feed ourselves, and forces have intervened over the last century that have disrupted those independent food resources, and it made it very challenging. But the desire and goal has always been there," said Thompson, whose tribal affiliation is Cheyenne River Sioux.

The MHA Nation's greenhouse plans are possible in large part because of access to potable water and natural gas resources.

The natural gas released in North Dakota's Bakken oil field has long been seen by critics as a waste and environmental concern, but Fox said the tribal nation intends to capture and compress that gas to heat and power the greenhouse and process into fertilizer.

Flaring, in which natural gas is burned off from pipes that emerge from the ground, has been a longtime issue in the No. 3 oil-producing state.

North Dakota Pipeline Authority Director Justin Kringstad said that key to capturing the gas is building needed infrastructure, as the MHA Nation intends to do.

"With those operators that are trying to get to that level of zero, it's certainly going to take more infrastructure, more buildout of pipes, processing plants, all of the above to stay on top of this issue," he said.

The Fort Berthold Reservation had nearly 3,000 active wells in April, when oil production totaled 203,000 barrels a day on the reservation. Oil production has helped the MHA Nation build schools, roads, housing and medical facilities, Fox said.

Native American news roundup, June 30-July 6, 2024

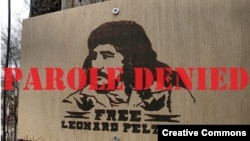

Leonard Peltier to remain in Florida prison

The U.S. Parole Commission this week denied parole for American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier, who has been incarcerated almost 50 years for the killing of two FBI agents.

Peltier was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder in the deaths of federal agents Jack Coler and Ronald Williams in a June 26, 1975, shooting on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences and has been in prison since 1976.

House Natural Resources Committee ranking member Raul Grijalva, a Democrat from Arizona, expressed his disappointment in the commission's ruling, saying, "The commission had the opportunity to take a small step toward rectifying a decadeslong injustice against Mr. Peltier, but incomprehensibly, they have opted against it."

Federal agents, past and present, hold that Peltier is guilty and shows no remorse for his crime. FBI Director Christopher Wray said in a statement that "justice continues to prevail."

Peltier has an interim hearing about his parole status scheduled for 2026 and a full hearing in 2039.

Read more:

Tribes want a say in Colorado River system water distribution

After a century of being excluded from the discussion, the 30 tribal nations that depend on the Colorado River system are fighting for a greater voice in determining its future when current operating agreements expire in 2026.

The 1922 Colorado River Compact regulated water distribution among seven southwestern states; tribes were not included in those negotiations. Despite holding senior water rights to about a quarter of the river's water, tribes lack access due to funding and legal issues, and this means their water flows downstream to other users.

In April, the Upper Colorado River Commission and six tribes with land in the Upper Basin signed a memorandum of understanding, agreeing to meet about every two months to discuss issues. Still, it does not give tribes a permanent seat on the commission, nor does it give them any authority to make decisions.

Read more:

California Franciscans: Extend deadline for clergy abuse claims for tribes we failed to notify

The Franciscan Province of St. Barbara is asking a bankruptcy court to extend the July 19 deadline for clergy sex abuse claims after a National Catholic Reporter, or NCR, investigation revealed that claim notices had not been sent to seven Native American tribes and communities in Arizona and New Mexico where abusive friars were known to serve.

The St. Barbara Franciscans filed for bankruptcy in late December 2023 in the face of dozens of new allegations of clergy sexual abuse.

A judge on May 22 ordered the St. Barbara Province to mail out "Sexual Abuse Claim Notice Packages" to eight state attorneys general, sheriffs’ offices and other agencies, and 27 newspapers, most of them in California.

The NCR compared the order with a list of "credibly accused" friars the St. Barbara Franciscans maintain on their website, noting that they had failed to send notices to the Colorado River Indian Tribes, Gila River Indian Community, Pascua Yaqui Tribe, San Carlos Apache Tribe, Tohono O'odham Nation and White Mountain Apache Tribe in Arizona, and the Mescalero Apache Tribe in New Mexico.

The Franciscans subsequently asked for the deadline to be extended to August 30 and notified the tribes.

BishopAccountability.org, which tracks clergy abuse cases, reports that 32 U.S. Catholic dioceses and three religious orders have filed for bankruptcy protection in the face of sex abuse accusations.

Read more:

North Carolina housing development is site of significant Native American village

A political fight is underway in North Carolina over what the state archaeologist has called one of the most significant finds ever uncovered — thousands of artifacts and evidence suggesting the presence of a Native American village occupied for centuries before European contact.

The discovery was made on a building site in Carteret County, where developers have already begun building housing.

The North Carolina Office of State Archaeology recommended exploration due to previous discoveries in the area from the 1970s. Construction halted as they dug 16 trenches across more than an acre, uncovering over 2,000 artifacts, including 11 potential human burial sites, 1,700 building post molds, 206 small pits, 45 large pits, 34 pits containing shells and more.

The developers' design engineer, however, dismissed the findings as a "Native American landfill" containing "nothing significant."

State Senator Michael Lazzara agrees and is pushing a bill that allows development to move forward.

Read more:

New theory emerges on Cahokia abandonment

Hundreds of years before Europeans arrived in the Western Hemisphere, Cahokia was the largest North American city north of Mexico and one of the biggest communities in the world.

Founded around 1050 by the Mississippian culture, Cahokia sat on the banks of the Mississippi River near present-day St. Louis, Missouri. At its height, Cahokia had a population of 50,000 but was deserted by 1400 CE. While scientists traditionally blamed drought and crop failure for its abandonment, a new study suggests otherwise.

Washington University researchers Natalie Mueller and Caitlin Rankin found no radical change in plant types.

"We saw no evidence that prairie grasses were taking over, which we would expect in a scenario where widespread crop failure was occurring," Mueller said.

Mueller believes the abandonment was gradual.

"I don't envision a scene where thousands of people were suddenly streaming out of town," she said. "People probably just spread out to be near kin or to find different opportunities."

Read more:

Ship traffic in Bering Strait a threat to Native Alaskan subsistence hunting

EDITOR'S NOTE: A previous version of this article misidentified Andrew Mew. A correction has been made.

Each spring, as the Alaska ice pack begins to loosen, Pacific walruses migrate north through the Bering Strait toward the colder waters of the Arctic Ocean. On their way, they pass Little Diomede Island, home of the federally recognized Native Village of Diomede (Inalik), nestled in the middle of the strait.

This is the time of year Inalik hunters set out in small boats, hoping to hunt and harvest enough walrus and oogruk (seal) to see them through the months ahead.

On June 14, Diomede's environmental coordinator Opik Ahkinga received a distressing Facebook message from an "outsider" asking whether she was aware that a large American cruise ship, Holland America's Westerdam, would be stopping for a "scenic tour" of Diomede in just five days.

"The Inalik Native Corporation and Native Village of Diomede have never given permission to the Holland America line to use Diomede Alaska as a scenic stop," Ahkinga told VOA. "If we're going to have ships come unannounced, there are going to be hunters out there still hunting."

The Westerdam, more than 285 meters (936 feet) long and 32 meters (106 feet) wide, was carrying some 1,700 passengers on a 28-day Arctic Circle cruise timed to coincide with the summer solstice.

It is a ship that would scare off any walruses in the area. Furthermore, where Diomede's hunters once used arrows and harpoons to hunt for food, today they use rifles, posing a danger to passing vessels.

Directing traffic

A U.N.-designated international strait, Bering is a key passageway for domestic and foreign-flagged vessels sailing from the Pacific Ocean to the Arctic. Increased mining and petroleum activities to the north have led to a dramatic increase in ship traffic through the strait.

In summer 2016, the Crystal Serenity made history with a 32-day cruise from Anchorage through the Northwest Passage to New York, via Greenland.

"That was big news, and there's been an uptick in cruise ships and sightseeing ever since," said Steve White, executive director of the Marine Exchange of Alaska, a Juneau-based nonprofit that works to prevent maritime disasters.

In 2018, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a U.N. Agency, adopted a set of routing measures for large vessels moving "in the region of the Alaska Aleutian Islands." Those included recommended routes, areas of concern and areas to be avoided.

But these measures are voluntary, and while numerous groups including the Coast Guard and Marine Exchange monitor vessel traffic, "overall, it's not heavily regulated," White said.

VOA reached out to the Anchorage-based Cruise Line Agencies of Alaska's vice president Andrew Mew, who responded by email about the potential conflicts between ships and Native Alaskans hunting, fishing and conducting other subsistence activities.

"We make a practice of alerting vessels to the presence of subsistence activities when we are advised of them by the Coast Guard or other agency or organization," wrote Mew.

"There are some existent agreements in place regarding subsistence and commercial vessel activity, but … I am not aware of any agreement between a local Arctic organization and the cruise industry relative to subsistence activity."

He added, "When approached by members of the subsistence community, we are happy to pass along courtesy notifications to the vessels."

Recognizing that there is no centralized mechanism for communicating with Indigenous communities, the Marine Exchange has launched the Arctic Watch Operations Center, which White says is still in its "infancy stages."

Once fully up and running, Arctic Watch will monitor marine traffic and weather conditions, identify areas to avoid because of marine presence and share that information with vessel operators, Arctic communities, Alaska Native tribal governments and state and federal agencies.

Effort pays off

Cell phone service on Little Diomede is spotty in the best of times. On June 14, it was down altogether.

But Ahkinga is among the few Diomeders who has access to satellite internet. With time running short, she began sending emails in an attempt to divert the Holland America cruise ship.

VOA has seen copies of that email chain, which shows that her appeals were successful. Within two days, the ship changed course.

"While we are not aware of any notifications required to sail in this area of the Bering Strait, when we received a request from the Inalik Native Corporation to avoid that part of the sea, we agreed to alter the route and informed our guests of the change," a spokesman for Holland America told VOA in an emailed statement.

"As a cruise line that sails across the globe, we are committed to honoring and respecting the marine environment and communities who welcome us in our travel."

Washington folklife festival honors Indigenous culture, communities

Washington's National Mall was buzzing with activity Wednesday, despite temperatures surpassing 36 degrees Celsius (96.8 Fahrenheit). Groups of children played lacrosse while the dynamic notes of music and the savory aromas of food wafted along the grassy blocks.

Visitors found themselves immersed in the first day of the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, running through July 1. This year, the festival celebrates Indigenous communities.

The festival, which calls itself "an exercise in cultural democracy," began in 1967. Its programming generally focuses on a nation, region, state, or theme, seeing hundreds of thousands of visitors per year. Since its founding, the festival has hosted more than 25,000 guest performers, cooks, artists, and speakers.

The 2024 festival has pivoted its focus, honoring Indigenous communities in alignment with the 20th anniversary of the National Museum of the American Indian, which is adjacent to the Mall. Around 60 countries are being represented throughout the festival.

"Change is very much part of the festival … It's not cookie-cutter. It allows us to be flexible and to lean into moments that really are important," Sabrina Motley, director of the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, told VOA.

This year's festival is also on the shorter side, spanning just six days instead of the typical 10.

"We wanted to use the time before the 4th of July. The building itself, the thing we're celebrating, has a different life on the 4th of July," said Motley.

"It is becoming increasingly more difficult to ask people to come to Washington for two weeks … I'd rather have the most wonderful artists and cooks and dancers and musicians that we can find here for six days than to try to squeeze the festival into a longer period, which would be harder on the people that we're really meant to honor," she added.

Celebration strengthens bonds, says official

The 2024 festival began with a welcome ceremony in the museum's Rasmuson Theater, followed by an outdoor presentation of colors with Native American Women Warriors. Simultaneously, events were already happening on the National Mall.

"Every day that we celebrate, every day that we dance and sing and pray, we strengthen the bonds that assimilation policies sought to break among Native people. Thank you for telling our stories and keeping them alive," said U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland at the welcome ceremony. Haaland is the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary.

Crowds attending the opening ceremonies spilled into the rest of the museum and the National Mall, where tents with music, food, and activities were scattered across the grass.

Each day of the festival has dozens of indoor and outdoor events from late morning to early evening. There are musical performances, cooking demonstrations, and speaker discussions. Several events occur at the same time, and most span less than an hour, allowing visitors to pop between tents and performances.

While scheduled events are occurring, the "Festival Kitchen," a tent pitched outside the museum, sells a variety of food, such as Peruvian chicken, chicken empanadas, and Mexican chocolate gelato.

Music, fritters, lacrosse lessons

Despite the ongoing heat, the first day had a range of events.