Native Americans

- By Steve Herman

Native American Languages Fight for Survival

Monday in the United States is celebrated as both Columbus Day and as Indigenous Peoples' Day.

When the Spanish-financed Italian explorer Christopher Columbus made contact with native inhabitants of the Caribbean in 1492, there were more than 500 languages spoken across the Americas. In the land that became the United States, the remaining number of such languages has dwindled to about 100. Most now have only a handful of speakers.

Alex Fire Thunder’s two young boys are a thriving exception as their ethnic Lakota language again has thousands of aspiring speakers.

“I want them to have a strong sense of their Lakota identity. Language is everything. It’s something that nobody can take away from them,” says Fire Thunder, Oglala Lakota from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota and deputy director of the Lakȟól'iyapi kiŋ nawéčižiŋ (Lakota Language Consortium).

Fire Thunder is optimistic his sons, Odowan, 3, and Iyoyanpa, 2, will have others besides themselves to converse in Lakota when they grow up.

“There are immersion schools. There are other second-language learners learning the language and teaching their children,” Fire Thunder, who has been among those formally teaching Lakota in schools, tells VOA.

That was not the case for decades.

“My mom is a speaker, but she did not transmit the language to my siblings and I,” he says.

For generations, Native American children in North America were sent to boarding schools where they were immersed in American culture and punished for speaking their own languages.

Teaching and learning these Indigenous languages in the 21st century are a challenge because there are scant resources and opportunities remaining.

“If you want to learn Spanish, there are a number of countries you can go to where all you’re going to hear is Spanish and you’re going to be expected to speak Spanish, as well,” Fire Thunder says.

For Lakota learners there are limited options. Some elders converse in Lakota at the post office or senior centers.

“The elders that do speak are, at this point and time, all bilingual so there is no situation where you absolutely have to use Lakota,” Fire Thunder explains. “That’s something you’re not going to find if you go to Spain or Mexico.”

Lakota is part of the Sioux language group and primarily heard in the Dakotas. A unique aspect of the language is the use of kinship terms, considered an essential to Lakota cultural expression, and many of the terms do not have precise English equivalents.

“There are only about 10 to 15 languages left in the U.S. that have any viable chances in terms of moving forward beyond the next 50 years,” according to Wilhelm Meya, chairman of The Language Conservancy.

When languages lose their last fluent speakers, it can also mean the demise of their Indigenous songs and prayers.

“The average speaker is about 75. Children for the most part are not learning the language,” Meya tells VOA. “So, there’s a lot to do in order to try to get these languages back on their feet.”

Meya’s organization is a nonprofit dedicated to preserving, protecting and promoting endangered languages. It currently partners with 52 Indigenous communities. One successful project has been the creation of the New Lakota Dictionary, considered the most expansive Native American dictionary.

Hundreds of Indigenous linguists, educators and scholars are to gather this week in Bloomington, Indiana, to share knowledge and inspire language revitalization efforts.

“For the elders and the speakers, they want to pass on the language, and they want to do so with hope they’re going to leave a legacy for generations going forward,” Meya says.

Native American News Roundup Oct. 1-7, 2023

Fentanyl is hitting tribes hard; lawmaker urges Senate investigation

U.S. Senator Maria Cantwell, a Democrat from Washington, this week called on the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs to investigate the disproportionate impact of the synthetic opioid fentanyl on Native American tribes.

“American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians are on the front lines of a deadly fentanyl epidemic and are suffering,” Cantwell said in an October 2 letter to Committee chairman Brian Schatz and vice chair Lisa Murkowski. “I believe we have a duty to Indian Country to examine this crisis and work with Tribes to save lives in their communities.”

Last month, Lummi Nation tribal chairman Anthony Hillaire declared a state of emergency after five tribe members died of fentanyl overdoses in one week. Among the steps the tribe is taking is evicting the residents of a house connected with the drug.

Elsewhere, tribal drug enforcement officers on the Tulalip reservation last week seized more than 50 so-called “rainbow” fentanyl pills.

“We have not seen them before,” Tulalip police chief Chris Sutter told VOA.

He counts close to 50 fentanyl-related deaths since joining the Tulalip police force in 2018.

Read more:

OAS reviewing Native American land case against US Government

The InterAmerican Commission on Human Rights, an arm of the Organization of American States, is for the first time reviewing a land rights case submitted by a Native American nation against the United States.

In 1788, the Onondaga Nation, one of the five original nations of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy, signed a treaty with New York state, believing that the agreement provided for the shared use -- not surrender -- of nearly 2,800 hectares of land.

Since then, the Onondaga have fought for the state and federal government to acknowledge that their land was illegally taken, and they say they’re not looking for a return of the land or any reparations.

The InterAmerican Commission on Human Rights in May agreed to review their case. According to the commission website, reviews typically take less than a year.

Read more:

Virginia, Oregon tribes seek a congressional path to federal recognition

Lawmakers from Virginia and Oregon have introduced legislation seeking federal recognition for tribes in their states:

U.S. Representative Abigail Spanberger, a Democrat from Virginia, and bipartisan co-sponsors introduced a bill in support of federal recognition for the Patawomeck Indian Tribe.

Elsewhere, U.S. Representatives Hillary Scholten, a Democrat from Michigan, and John Moolenaar, a Republican from Michigan, introduced a bill calling for recognition of the Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians.

The U.S. government recognizes 574 tribes, mostly through historic treaties, making them eligible for benefits and protections.

As VOA has previously reported, non-treaty tribes who want recognition must petition the U.S. Interior Department (DOI) and meet seven strict criteria. They also have the option to bypass DOI and directly petition Congress.

Virginia tribes like the Patawomeck have a hard time meeting some of these criteria owing to records destroyed in the Civil War and a 1924 state law that classified individuals as either Black or white.

The Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians petitioned DOI for recognition in 2013 but were rejected on the grounds that they have not existed as a continuously existing community since historical times.

Read more:

Pretendian art dealer sentenced

A federal judge in Washington state has sentenced a Seattle artist to 24 months’ probation and 200 hours of community service for violating the Indian Arts and Crafts Act.

The case stems from an anonymous complaint in 2018 that Lewis Anthony Rath was selling carvings and jewelry, falsely claiming to be a member of the San Carlos Apache Tribe in Arizona.

“Counterfeit Indian art, like Lewis Anthony Rath’s carvings and jewelry that he misrepresented and sold as San Carlos Apache-made, tears at the very fabric of Indian culture, livelihoods and communities,” said Meridith Stanton, director of the DOI Indian Arts and Crafts Board, “…Mr. Rath’s actions demean and rob authentic Indian artists who rely on the creation and sale of their artwork to put food on the table, make ends meet, and pass along these important cultural traditions and skills from one generation to the next.”

Read more:

Scholar: Indigenous Peoples Day an occasion to reflect

In the United States, October 9 is still the federal holiday Columbus Day, honoring the Italian explorer Christopher Colombus. But growing numbers of states and localities have chosen to observe the day as Indigenous Peoples Day or Native American Day, acknowledging the peoples who inhabited the continent many millennia before Columbus’ “discovery.”

University of Massachusetts Lowell history chair Chrisoph Strobel, an expert in colonial-Indigenous relations, this week notes that the day should serve as a reminder not only of Indigenous resilience but of the violence Indigenous peoples endured historically.

He examines the practice of scalping, which popular culture suggests was only practiced by Indigenous Americans.

“White settlers’ wide use of scalping against Indigenous peoples is far less acknowledged and understood,” he writes, noting that they were often encouraged by scalp bounties offering money for Indian scalps.

Read more:

Federal Appeals Court Considering Native Americans Challenge to Copper Mine

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals is considering an appeal from a Native American group seeking to block the development of a copper mine on Arizona land sacred to Western Apache. VOA reporter Levi Stallings filed this story from Oak Flat.

US Agrees to Help Restore Sacred Site Destroyed for Road Project

The U.S. government has agreed to help restore a sacred Native American site on the slopes of Oregon's Mount Hood that was destroyed by highway construction, court documents show, capping more than 15 years of legal battles that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In a settlement filed with the high court Thursday, the U.S. Department of Transportation and other federal agencies agreed to replant trees and aid in efforts to rebuild an altar at a site along U.S. Highway 26 that tribes said had been used for religious purposes since time immemorial.

Members of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation and the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde said a 2008 project to add a turn lane on the highway destroyed an area known as the Place of Big Big Trees, which was home to a burial ground, a historic campground, medicinal plants, old-growth Douglas firs and a stone altar.

Carol Logan, an elder and member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde who was a plaintiff in the case, said she hopes the settlement would prevent the destruction of similar sites in the future.

"Our sacred places may not look like the buildings where most Americans worship, but they deserve the same protection, dignity, and respect," Logan said in a statement shared by the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, which represented the plaintiffs in their lawsuit.

The defendants included the Department of Transportation and its Federal Highway Administration division; the Department of the Interior and its Bureau of Land Management; and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

The Federal Highway Administration and the Department of the Interior declined to comment on the settlement.

In court documents dating back to 2008 when the suit was filed, Logan and Wilbur Slockish, who is a hereditary chief of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, said they visited the site for decades to pray, gather sacred plants and pay respects to their ancestors until it was demolished.

They accused the agencies involved of violating, among other things, their religious freedom and the National Historic Preservation Act, which requires tribal consultation when a federal project may affect places that are on tribal lands or of cultural or historic significance to a tribe.

Under the settlement, the government agreed to plant nearly 30 trees on the parcel and maintain them through watering and other means for at least three years.

They also agreed to help restore the stone altar, install a sign explaining its importance to Native Americans and grant Logan and Slockish access to the surrounding area for cultural purposes.

Native American News Roundup September 24–30, 2023

Opinion: Federal shutdown would be 'bad for Indian Country and the whole country'

Native News Online this week outlined the ways a federal shutdown would affect the 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S.:

Federally funded tribal programs would not see any new funds until funding bills pass.

If tribes have funds left over from previous years, they could use those funds to continue program operations and pay employees until those funds run dry.

If tribes do not have any leftover funds, they will be forced to find other funding sources or shutter programs entirely.

"Past government shutdowns have taken the lives of Native citizens, harmed their well-being, and forced tribal governments, tribal organizations, and individual citizens to go into debt to cover the United States' broken promises," editor Levi Rickert writes.

Parts of the federal government would cease operations if there is a lapse in appropriations caused by the absence of funding before the start of the new fiscal year October 1.

Read more:

White House orders agencies: Restore fish to Columbia River Basin

This week, President Joe Biden ordered federal departments and agencies to do what it takes to restore healthy fish populations in the Columbia River Basin.

"It is a priority of my Administration to honor Federal trust and treaty responsibilities to Tribal Nations — including to those Tribal Nations harmed by the construction and operation of Federal dams," Biden said in a presidential memorandum released Wednesday.

To that end, Biden gave departments and agencies 120 days to review any programs affecting salmon, steelhead and other native fish populations in the basin and an additional 100 days to report to the Office of Management and Budget what changes they will make and what they will need to get the job done.

Salmon once occupied nearly 13,000 miles of Columbia River Basin streams and rivers and were a mainstay of regional tribal economies and cultures.

Read more:

Interior Department to document, make public, Native American boarding school stories

The Interior Department this week announced a new project to document and make available to the public stories of Native American children forced into the federal Indian boarding school system.

"Creating a permanent oral history collection about the federal Indian boarding school system is part of the Department's mission to honor its political, trust and legal responsibilities and commitments to Tribes," said Secretary Deb Haaland in a statement Tuesday.

"The U.S. government has never before collected the experiences of boarding school survivors, which Tribes have long advocated for to memorialize the experiences of their citizens who attended federal boarding schools. This is a significant step in our efforts to help communities heal and to tell the full story of America."

The Department has granted $3.7 million to the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) to interview former students and their descendants and will shortly announce dates, times and locations for those interviews. Interested parties can sign up on the NABS website:

Read more:

Homeless crisis prompts tribe to enact state of emergency

Inflation and the rising cost of housing in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic have exacted a heavy toll on the Mashpee Wampanoag in Massachusetts. The resulting rise in homelessness prompted tribal leadership last week to enact a state of emergency.

"We are hoping the state of emergency can help us to get more federal funds and grants to eventually structure our own tribal housing authority through the tribe's Housing Department," tribal chairman Brian Weeden said.

Last year, the tribe used nearly $2 million in American Rescue Plan Act and U.S. Housing and Urban Development funding to purchase a 19-room motel which it hopes can eventually serve as transitioning shelter for tribe members in need.

"But it's not enough," Weeden said.

The council also pledged to work with local, regional, state and federal agencies and organizations to look for other solutions to the housing crisis.

Read more:

Commanders vs. 'Redskins': Nonprofit to take football team and Native advocacy group to court

A North Dakota-based nonprofit organization has filed a defamation lawsuit against the Washington Commanders football team, its leaders and the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI).

The Native American Guardians Association (NAGA) lawsuit, filed in a U.S. district court in North Dakota, accuses the Commanders and its leaders, working in tandem with NCAI, of defaming NAGA as a "fake" group comprised of "fake Native Americans."

NAGA's website states: "Each member of our leadership team has some verified Native ancestry with the majority being enrolled tribal members."

NAGA in August sent a three-page letter to the owners and leaders of the Washington Commanders, calling on them to restore the team's former name, the "Washington Redskins" and "stop the further cancel culture" against Native Americans.

The group cites a 2016 Washington Post poll of 504 Native Americans, the majority of whom said they were not offended by the "Redskins" name.

In 2020 however, University of Michigan and University of California, Berkeley researchers polled 1,000 Native Americans on their perceptions of the "Redskins" name; 49% said they found it offensive.

The National Football League team dropped the "Redskins" name in 2020 and was known simply as the Washington Football Team before adopting the Commanders name in 2022.

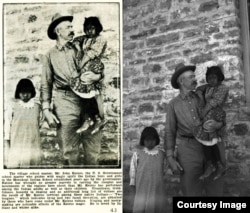

Reporter's Notebook: For More Than 20 Years, Ancestor Led or Taught at Various Indian Boarding and Day Schools

Editor’s Note: This is the last story in a three-part series that explores the history of the federal Indian school on the Western side of the Navajo Nation in Arizona -- and a man who taught there and in other Indian schools for more than two decades.

The 1901 Course of Study for the Indian Schools reflects the federal mission to turn Native Americans into farmers and housekeepers: Children were to spend half the day in classrooms, learning basic reading, writing and arithmetic, and spend the remainder of the day working in kitchens, fields, blacksmith shops or print shops.

There was little time for leisure: “One evening in the week should be a social hour, when the pupils may spend the evening in conversation, grand marches, etc., under the direction of the teachers,” the guide states.

On remaining evenings, teachers from various departments lectured students on farming, shoemaking and cooking so that “each child shall grasp a practical thought that may be applied in the work to be done.”

In the summer, schools were encouraged to send children on “outings” in non-Native homes and farms in the summer, where they would gain “practical experience” for their future occupations.

Some Tuba City boys were sent to work as seasonal labor in Colorado beet fields. Others remained behind to tend to the school farm.

Overworked and overtired, it is little wonder they were vulnerable to infection and disease.

‘Frothing at the mouth’

Students and staff were hit hard during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. Brigham Young University anthropologist Albert B. Reagan visited Tuba City and pitched in to care for stricken students. The Kansas Academy of Science later published his harrowing account:

“Twenty-three of my boys were frothing at the mouth, and some were delirious … sanitary conditions had gotten very bad, as many of the children were wholly helpless…” he wrote. “Two of the girls died, both at night, and on account of the Navajos’ fear of death and the dead, we had to carry them out of the dormitory … with lights darkened so the other pupils would not see what we were doing.”

My great-grandfather was detailed to the Hopi day school at Moenkopi and was “overwhelmed” with caring for sick students and their families. Reagan noted that he was “heroically aided by Mr. Curn [sic] in every way possible.” They purchased sheep from a local herder and made a 75-liter (20-gallon) pot of soup which they distributed by car to the families.

“Of the 300 who were sick, only 16 died,” Reagan wrote.

In 1922, the American Red Cross (ARC) sent nurse Florence Patterson to visit several Southwestern reservations to determine whether there was a need for public health nurses.

In November 1928, Patterson told a Senate subcommittee on Indian Affairs that children at the Tuba City school were served bread, coffee and syrup for breakfast and bread and boiled potatoes at midday dinner and supper. Though the school had a dairy, only a small amount of milk was made available and was given only to “the big boys.” Children as young as 5 were given only coffee or tea.

The children were not given any of the fruit or vegetables they grew, Patterson said. These were sold to help keep the school funded.

During the same hearings, Stella Atwood, a California advocate for Native rights, testified that 11 out of 44 little boys sent to work in Colorado’s beet fields came back with typhoid; two died on the road back to school; the fate of the others isn’t known.

Over the next 20 years, Keirn bounced from the Tuba City boarding school, teaching Navajo, Hopi and Paiute children, to the nearby Hopi day school at Moenkopi. Records alternately describe him as teacher, principal or “headman.”

A family photo dated July 20, 1915, shows my great-grandfather, his wife and two older children descending the Grand Canyon by mule.

John divorced Clara in 1918, but they would be together at the newly established Theodore Roosevelt Indian School on the White Mountain Apache Reservation, where Clara contracted and died of diphtheria.

John left the Indian service in the mid-1930s and moved to California, hoping to stay with his son and daughter-in-law, who was my grandmother. Years later, she told me that the aging Keirn was demanding and ill-tempered, and they asked him to leave.

In 1941, at the age of 81, he died from complications of surgery.

Reconciling the past

I am still processing everything I have learned and hope that the ongoing Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, which launched in June 2021, will tell me more.

It is stunning to me that newspapers and genealogical and government archives were able to tell me the life story of my ancestor — a white man — but nothing about the hundreds of children he taught or the emotional, physical and spiritual hardships they may have endured.

I scan his face in the photograph above but I can’t find any clues to his personality and cannot trust the glowing description of him in the clipping above as "loved by Indians and whites alike."

The little girls' expressions speak for themselves.

Most teachers didn’t last long in service, but John Keirn stayed in Arizona for more than two decades. I would like to believe that he was one of those idealistic reformers that historian Williams writes about, but instinct tells me otherwise.

Today, Americans are locked in debate over what — if any — responsibility they hold for the racist policies of the past and whether that history should be taught to future generations.

As a reporter covering Native American issues, I have had several conversations with boarding school survivors and heard heartbreaking stories about the physical, sexual and psychological abuses they endured. Discovering that a family member was complicit in a scheme to undermine Native cultures has further strengthened my resolve to learn more about how historic policies impact tribe members and their communities today.

Today, the Tuba City Boarding School is a modern facility operating under the U.S. Bureau of Indian Education. Its stated mission is to educate Navajo and Hopi children from kindergarten through eighth grade “in a safe and culturally competent environment.”

“We are running a lot of good programs here, and parents are excited about what's going on,” principal Don Coffland told me by phone. “So, we're really proud of what we do here.”

To learn more about the school, watch this student-produced video.