Native Americans

Native American News Roundup September 17 to 23, 2023

Here are some of the Native American-related stories making headlines this week:

Lawmakers seek to combat child abuse, neglect and family violence

The U.S. House of Representatives this week passed the Native American Child Protection Act to help Native American communities respond to and head off family violence and child abuse.

Introduced by Representative Ruben Gallego, the Native American Child Protection Act revises programs that were originally established in 1990 and passed as part of then-Senator John McCain's Indian Child Protection and Family Violence Prevention Act.

Its provisions are aimed at helping tribes develop programs to identify, investigate and prosecute cases of child abuse, child neglect and family violence.

“For too long, Congress has failed to uphold its promise to address the disproportionate levels of child abuse in tribal communities,” said Gallego, former chairman of the House Subcommittee on Indigenous Peoples of the U.S. “My bipartisan Native American Child Protection Act corrects that by providing tribes the resources they need to prevent, prosecute, and treat instances of family violence and child abuse.”

The bill now passes to the Senate for consideration.

BIA’s Missing and Murdered Unit steps in where law enforcement has failed

Agents from the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Missing and Murdered Unit are reexamining the case of Kaysera Stops Pretty Places, who went missing on August 24, 2019, in a suburban neighborhood of Hardin, Montana, less than 0.8 kilometers from the Crow Reservation boundary.

Law enforcement found her body five days after she disappeared but did not notify her family until September 11. Since then, the family says it has not heard from the Big Horn County Sheriff’s office, the FBI or the Montana Justice Department about investigations into her death.

The BIA unit was formed in 2021 by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and has received 845 case referrals, primarily from victims’ families. Nearly 375 cases are still under review or being investigated.

Read more:

White House to boost restoration of Columbia River Basin salmon

The Biden-Harris administration this week announced a historic agreement with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, and the Spokane Tribe of Indians to reintroduce salmon into blocked habitats of the Upper Columbia River Basin.

Salmon were once abundant in the upper Columbia, Sanpoil, and Spokane rivers but disappeared after their habitats were blocked by the construction of hydroelectric dams in the 20th century.

As a result, tribal communities have had to change their traditional diets and traditional ways of life, and this in turn has changed the way they once taught and raised children in the cultural and spiritual beliefs centered around these fish.

“Since time immemorial, tribes along the Columbia River System have relied on Pacific salmon, steelhead, and other native fish species for sustenance and their cultural and spiritual ways of life. Today’s historic agreement is integral to helping restore healthy and abundant fish populations to these communities,” said Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said.

The agreement includes funding to support implementing these plans, including $200 million over 20 years from the U.S. Energy Department and $8 million over two years through the Bureau of Reclamation.

Read more:

Southern Baptists expel church after pastor defended racist role play

The Southern Baptist Convention, America’s largest Protestant organization, this week voted to oust an Oklahoma pastor in Ochelata who failed to respond to allegations that his church “affirms, approves, or endorses discriminatory behavior on the basis of ethnicity.”

While the convention didn’t offer further details, it is believed to be related to two Matoaka Baptist Church events in which pastor Sherman Jaquess dressed in blackface and as a “Native American.”

The Convention’s Executive Committee voted Tuesday that the Matoaka Baptist Church was “deemed not in friendly cooperation with the convention” — the official terminology for an expulsion.

In a video released on Facebook earlier this year, Jaquess can be seen at a 2017 Valentine’s Day event dressed in blackface at a piano, posing as singer Ray Charles.

A separate Facebook photo shows Jaquess at a 2012 youth camp event dressed in red face, wearing "Native American" braids and a feathered headband.

Jaquess defended his actions, saying that it is "repugnant to have people think you're a racist" and claimed that he was paying tribute to the iconic soul singer.

"It wasn't derogatory, wasn't racial in any way, and we're not racist at all,” he said. “I don't have a racist bone in my body. I have a lot of racial friends."

He also stated he is of part-Cherokee heritage.

Read more:

Native American earthworks listed as World Heritage Site

The UNESCO World Heritage Committee this week added 27 new sites to the World Heritage List, among them the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks in southern Ohio. Those are eight enormous earthen enclosure complexes that American Indians — known as the Hopewell Culture — built between 1,600 and 2,000 years ago.

These served as centers for Hopewell feasts, funerals, and other social and spiritual gatherings. Archaeologists excavating the site have found pottery, copper and shell ornaments, and carved pipes made from raw materials obtained through trade with tribes in the Great Lakes, Carolinas, the Rocky Mountains and elsewhere.

Read more:

Danish trolls come to Seattle

John “Coyote” Halliday, an artist enrolled in the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe in Washington State, helped design one of six gigantic trolls that have appeared in the Puget Sound area.

Standing as tall as 6 meters, they are all made from recycled materials.

It is part of a larger body of work conceived by Danish artist/activist Thomas Dambo, to bring attention to sustainability and the environment.

VOA reporter Natasha Mozgovaya spoke with Halliday and Dambo in Seattle and filed this report.

UPDATE: Seattle's KOMO News reports that vandals defaced the troll sculpture featured in Natasha Mozgovaya's video report. Read more:

Reporter's Notebook: Ancestor Appointed to Teach at Western Navajo Agency in Arizona

Editor’s Note: This story is the second in a three-part series that explores the history of the federal Indian school on the Western side of the Navajo Nation in Arizona -- and a man who taught there and in a nearby day school for more than two decades.

John A. Keirn was appointed a teacher at the Western Navajo Agency in Arizona, effective November 1912, earning $84 a month on a probationary basis, according to the Haskell Indian boarding school newspaper, The Indian Leader, which tracked appointments, transfers and retirements in the Indian Service.

When Keirn arrived in Arizona, it had been 50 years since the U.S. Army began rounding up and force-marching groups of Navajo along the “Long Walk” to an internment camp at Bosque Redondo, along the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico.

The plan had been to turn the Navajo into farmers, but the experiment failed: crops failed repeatedly, conditions were bleak and the government, which was spending $1.5 million a year to feed the prisoners, finally relented and freed them.

In 1868, U.S. officials negotiated a treaty that established the Navajo reservation, which completely encircled the homelands of the Hopi. In 1882, Washington established the Hopi (then known as Moqui) reservation, which included a summer farming community at Moenkopi, 3 kilometers outside of Tuba City, which was part of the Navajo Nation.

Army campaigns against Native tribes in the Southwest ended with the capture of the Apache leader Geronimo in 1886; now, the U.S. turned its attention from warfare to forced assimilation.

U.S. Army General Richard H. Pratt in 1878 had established the first of many federal off-reservation Indian boarding schools in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. By 1908, the government was operating 88 reservation boarding schools, 26 non-reservation schools and 165 day schools.

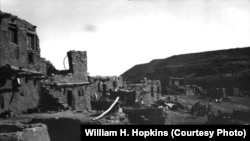

These included the Keams Canyon Boarding School for the Hopi (then called Moqui), which, like many boarding schools would come to be known by several names, and the Western Navajo Agency Boarding School, established at an abandoned trading post at Algert, in Arizona’s Blue Canyon.

When the government failed to make needed improvements to the Blue Canyon site, school staff, students and local Navajo stonemasons hauled stone and constructed their own school buildings.

“Oil-can cases were used for window frames and goods boxes were utilized for lumber to make doors, etc.,” the agency superintendent wrote in his 1901 report to the Commissioner for Indian Affairs in Washington.

In 1903, the government moved its Western Navajo Agency headquarters to Tuba City, an oasis fed by a tributary of the Little Colorado River. The city’s name belied its size; at the time, it consisted only of a trading post and a handful of buildings left by earlier Mormon settlers.

In 1904, the government began constructing a new boarding school to replace the Blue Canyon school: The new Tuba City Boarding School was comprised of three imposing buildings, arranged symmetrically in an architectural style typical of federal buildings at the time.

“Such an arrangement suggests both system and the authoritative, almost military-like, approach to education that dominated BIA thinking through the first two decades of this century,” reads a National Park Service survey of the buildings.

The children slept in “large impersonal sleeping rooms” that doubled as classrooms. As the student population grew, the agency added 40-bed sleeping porches to the boys’ and girls’ dormitories.

Gradually, the school expanded to include a classroom building, mess hall, steam laundry and employee living quarters. By the late 1920s, the campus included a 50-bed hospital, barn, garages and machine shop.

Bugles and drills

In her 1954 memoir “The Red Moon Called Me,” Gertrude Golden, a teacher in the Indian Service from 1901 to 1918, described student life in non-reservation boarding schools as highly regimented.

“The pupils were divided into companies according to age and size, and each company had its captain, lieutenants and corporals,” she wrote. “These officers drilled their companies in marching, setting-up exercises and simple military maneuvers.”

In his 1914 annual report to the Interior Secretary for 1913, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Cato Sells said that as a means to ensure uniform systems of drilling in these schools, “a pamphlet has been published for the use of employees reproducing a portion of the Manual for Infantry Drills now used by the United States Army.”

A former student at the Tuba City school would later recall: “In the morning, the bugle would blow, and all the children would go out and line up to salute the flag while the bugler played, and then they marched to the dining hall.”

Tuba City students earned their keep working on the school’s 200-acre farm, which included garden plots, a large apple and pear orchard, and about 40 hectares each of alfalfa and corn.

Students raised and butchered their own livestock, canned fruits and vegetables for the winter, and in cold months, harvested ice for summer.

Sometime before 1920, my great-grandfather took a series of photographs (see photo gallery, below). These ended up in Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, which digitized them for VOA. Because the children are young, I assume that they were Hopi children attending the Moenkopi Day School.

Never made public before, the photos (above) are gut-wrenching: children, some of them not much older than 4 or 5, stand in the hot sun behind mounds of picked apples; boys lean on hoes amid rows of what appears to be lettuce.

One photograph shows the children holding Navajo rugs and popular monthly magazines like McClure’s, which would have been completely foreign to them, both in language and cultural content.

Not one child is smiling.

NOTE: Part Three of the series examines student health and nutrition.

Reporter's Notebook: Finding That My Ancestor Taught in an Indian Boarding School

Editor’s Note: This story is the first in a three-part series that explores the history of the federal Indian school on the Western side of the Navajo Nation in Arizona — and a man who taught there and in a nearby day school for more than two decades.

One Sunday last May, I logged into a popular genealogical site to research my family tree. Specifically, I wanted to know more about my mother’s grandfather, John A. Keirn, who had left his wife and three children and moved out West.

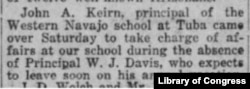

Searching his name in newspaper archives, I was shocked to find a small notice in the August 5, 1927, issue of Arizona’s Coconino Times newspaper: Keirn had been the principal of the Western Navajo Indian boarding school in Tuba City, Arizona.

Keirn was my ancestor by marriage, not by blood; but that did not make him any less family. His son, my step-grandfather, had been an important influence growing up. I felt embarrassed, almost betrayed, having researched and written about some of the horrors perpetrated at schools like this one.

And then I remembered hearing he had a bad temper. That bothered me more than anything else. I wondered how many children had felt its sting.

I had to know more.

Digging through archives

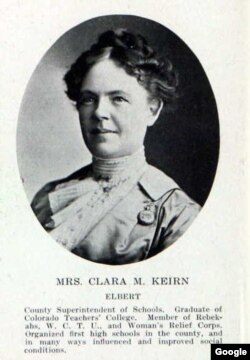

Census records show Keirn, the son of a farmer, moved from Illinois to Omaha, Nebraska, in the early 1890s to teach school. There, he met his future wife, fellow teacher Clara Rood. They married in 1896 and eight years later moved to rural Elbert County, Colorado, where Clara got a job teaching.

At the time, schools in rural counties were makeshift and scattered: Clara rode on horseback from one school to another. In 1907, she was elected president of her school district and in 1908, promoted to county superintendent of schools.

But her husband was not so lucky. He drifted from one job to another — working at the local mercantile store or on a railroad bridge gang.

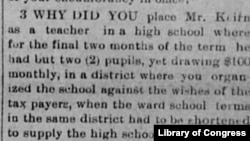

In November 1912, Clara was up for reelection and nearly lost over public charges of nepotism: She had opened the county’s first high school and appointed her husband as its sole teacher. He was earning $100 a month — a generous salary — to teach only two students.

Voters also questioned why the couple’s oldest daughter had been sent away to school in Omaha instead of attending one of the schools that Clara supervised.

Ten days after the allegations surfaced, the Elbert County Tribune reported that John Keirn had left Colorado for Arizona.

Vocation, escape or last resort?

It is hard to imagine what motivated my great-grandfather to leave a wife and three children — the youngest, my step-grandfather, only a boy of 7 — to join the Indian service.

Denver was only 80 kilometers (50 miles) away and by 1912 had a well-established school system.

It is possible that Keirn could not meet Denver’s hiring requirements: A 1928 report of conditions on Indian reservations — a so-called Meriam Report — noted that the government regularly hired teachers whose credentials would not be accepted by any good public school system.

“… there is even some evidence that the Indian Service is receiving teachers who have been forced out of the schools of their own states because they could not meet the raised standards of those state,” investigators said.

Historian David Wallace Adams, author of “Education for Extinction,” writes that some teachers were driven by “a sense of Christian responsibility to save a vanishing race from extinction.”

In her 1954 memoir “Red Moon Called Me,” Gertrude Golden, a former teacher in the Indian Service, noted that when Native American children were fortunate enough to have good teachers, “inestimable good was accomplished.”

“But it happened all too frequently that the teacher was in the work only for money and adventure and acted upon the principle that ‘anything is good enough for a lousy Indian,’” she wrote.

Another possibility is that Keirn was looking to leave his marriage.

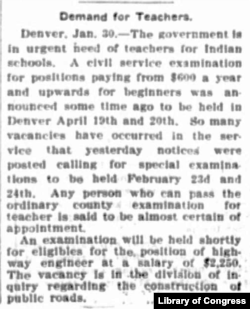

Whatever his motive, he would have seen one of the job notices that the U.S. Civil Service Commission periodically published in regional newspapers.

He would have had to pass a civil service examination requiring him to write neatly, spell correctly, draw a simple picture and write brief essays on questions in basic algebra, geography, history, physiology and hygiene, nature study and American literature. The U.S. Civil Service Commission (CSC) published sample questions such as:

“Compare Ohio and Cuba as to climate, physical features, vegetation, leading industries, character of inhabitants, form of government, etc.”

“Discuss the peculiarities, characteristics, habits, etc., of the bobolink [a songbird], including food, mode of nesting and rearing young, etc.”

“A field is in the form of an isosceles triangle. The two sides are 26 rods each and the base is 20 rods. What is the altitude?”

The CSC cautioned applicants: “The object of the schools is to prepare the Indian youth for the duties, privileges and responsibilities of American citizenship by training them in the industrial arts and developing their moral and intellectual faculties ...“The conditions of life at these schools differ from ordinary school or home life … There is little opportunity for recreation or social pleasure."

NOTE: Part Two of this series will explore student life at the Tuba City Boarding School.

Native American News Roundup September 10-16, 2023

Leonard Peltier supporters arrested, fined during Washington protests

U.S. Park Police issued citations to more than two dozen supporters of imprisoned Native American activist Leonard Peltier during a rally outside the White House Tuesday.

The event was co-hosted by the South Dakota-based activist group NDN Collective and the human rights group Amnesty International.

As VOA reported in 2016, Peltier, an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa tribe of Lakota and Dakota descent, was convicted in the murders of two FBI agents during a 1975 standoff at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota and given two consecutive life sentences.

His supporters say he was framed for murders he didn’t commit. Federal agents say evidence shows he was guilty of shooting agents at close range and that he has shown no remorse.

Peltier, 79 and in ill health, has spent 46 years in prison, losing multiple appeals for parole and White House clemency.

The U.S. Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 allows “compassionate release” for prisoners over 70 who have completed at least 30 years of their sentences. But because Peltier was sentenced before the law went into effect, he is ineligible.

“We come together here to remind the United States that Leonard Peltier is the longest-incarcerated political prisoner in the history of the United States,” NDN Collective CEO Nick Tilsen (Oglala Lakota) said Tuesday. “… We cannot let his fight for freedom go quietly. It's time — 48 years is long enough.”

Park Police spokesman Sergeant Thomas Twiname said that officers issued citations to 27 demonstrators for the misdemeanor violation of “incommoding,” that is, crowding or obstructing a sidewalk.

“Nobody was put in handcuffs,” he said. “They were given citations, and then the individuals left.”

Indigenous researchers stress Indigenous sovereignty over biomedical data

The Daily Yonder this week highlights the work of the Native BioData Consortium (NativeBio), a nonprofit research collective led by Indigenous scientists and scholars seeking to use health data to improve and protect the health, welfare and cultures of Indigenous peoples.

Government agencies and scientific researchers have a history of unethical research among Native Americans. In the 1950s, for example, the U.S. Air Force gave capsules filled with radioactive Iodine-131 to Alaska Natives as part of a thyroid function study, putting them at risk of developing thyroid cancer.

In the early 1990s, an Arizona State University professor took blood samples from the Havasupai Tribe to understand the prevalence of diabetes in that community. Those samples ended up in the hands of researchers in other institutions, who used them for research on schizophrenia, inbreeding and theories about ancient migrations from Asia to North America.

NativeBio, located on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, works to break down mistrust of science.

“Our main mission is to be a safe harbor for all indigenous people, and even marginalized people around the world whose data has been collected since the ‘70s and is being collected now, and not giving them enough consideration or control of how their data is used or commercialized,” said Joseph Yracheta, executive director of NativeBio.

Read more:

Native tribes, mining groups, at odds over massive lithium find in Nevada

Scientists say that lithium discovered three years ago in a collapsed supervolcano in Nevada could meet global demand for decades.

A new analysis of the southern portion of the McDermitt caldera in Nevada called Thacker Pass shows that claystone made up of the mineral illite contains 1.3% to 2.4% of lithium in the crater, nearly double the levels in more common lithium-bearing magnesian smectite clay.

Since 2021, local tribes and environmental groups have tried without success to halt mining construction at Thacker Pass, which lies in the traditional homelands of the Paiute, Shoshone and Washoe people.

Read more:

US court sentences man for looting Native American archaeological site

A California man has been sentenced to three years of probation and ordered to pay more than $10,000 in restitution for illegally digging up and removing Native American human remains and cultural artifacts from public land in violation of federal law.

The case dates to July 2015, when wildfire fighters stumbled upon an excavated site in the Sierra National Forest.

“Human remains and artifacts were located among large piles of sifted dirt, hand tools and a large screen sifting box,” the Justice Department stated in 2018.

A video camera at the site captured Vance Franklin Myers excavating the site multiple times, sometimes in the company of a woman, a small child and a dog.

The items he looted were valued at nearly $60,000.

Archaeologists stabilized the site, human remains were reburied, and artifacts were returned to the North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians.

Read more:

Native American News Roundup September 3 – 9, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Interior Department cancels Arctic oil and gas leases

The Biden-Harris administration announced this week that it will cancel oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) purchased by state developers on the last day of the Trump administration.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said Wednesday that the “lease sale itself was seriously flawed and based on a number of fundamental legal deficiencies.”

“With today’s action, no one will have rights to drill for oil in one of the most sensitive landscapes on Earth,” Haaland told reporters. “Climate change is the crisis of our lifetime, and we cannot ignore the disproportionate impacts being felt in the Arctic.”

The administration will also ban new leasing on more than 10 million acres in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, the largest undisturbed public land in the United States.

Forty-year fight

In 1980, Congress opened 1.5 million acres inside the refuge to oil and gas development. In 2017, Congress passed a tax reform bill authorizing the Interior Department to hold two lease sales by the end of 2024.

The state’s own economic development arm -- the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA) – bought 10-year leases covering more than 174,000 hectares (430,000 acres) of land.

The land in question is estimated to hold more than 7 million barrels of oil and 198 billion cubic meters (7 billion cubic feet) of natural gas.

In June 2021, the Biden administration put a hold on all drilling, pending an environmental review. AIDEA sued Biden and several other administration officials.

“The lawsuit is in direct response to unlawful actions to obstruct and delay the development of valid oil and gas leases in the non-wilderness Coastal Plain (Section 1002 Area) of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR),” AIDEA said in a press release at the time.

Last month, a federal judge dismissed the suit.

Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy was quick to react to Haaland’s announcement this week.

“The leases AIDEA hold in ANWR were legally issued in a sale mandated by Congress. It’s clear that President [Joe] Biden needs a refresher on the Constitution’s separation of powers doctrine. Federal agencies don’t get to rewrite laws, and that is exactly what the Department of the Interior is trying to do here,” he said.

AIDAI said it will continue to “aggressively defend” its lease rights.

Read more:

Cherokee Chief condemns Oklahoma governor's pick for tribal liaison

Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt, a member of the Cherokee Nation, has added a Native American tribal liaison to his leadership team. His choice is John Wesley “Wes” Nofire, a retired boxer, former member of the Cherokee Nation tribal council and harsh critic of principal chief Chuck Hoskin Jr.

In a statement released Tuesday, Stitt’s office described Nofire as “outspoken about the challenges the Supreme Court’s McGirt decision has created when it comes to administering justice fairly for every Oklahoman, native and non-native alike.”

In McGirt v. Oklahoma, U.S. Supreme Court justices reviewed the case of a Native American accused of the rape of a 4-year-old Native child on the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. An Oklahoma court sentenced him to two 500-year sentences and life without parole.

More than 20 years later, his lawyers appealed, arguing that because Congress had never formally disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the crime took place on tribal land. They cited the Major Crimes Act, an 1885 law that says when serious crimes are committed by or against a tribal member on tribal or reservation land, only the federal government, not the state, has the right to prosecute.

The Supreme Court agreed.

Though the ruling applies only to criminal jurisdiction, many in Oklahoma worry it could expand to other areas of law enforcement and beyond into environmental and energy arenas.

Hoskin took to Facebook to condemn Nofire, whose political views are said to align with Stitt’s.

“It’s difficult to overstate the active threat that Governor Stitt’s new Native American Liaison, Wes Nofire, poses to tribal sovereignty,” he wrote. “He is on the record opposing tribal sovereignty and peddles dangerous and unhinged conspiracy theories.”

In an interview with Oklahoma’s KOKO-TV, Nofire sent a message to Hoskin and other critics:

"Give me a little bit more time and allow me to be that olive branch. It grows. That’s one thing that they do is when we reach out the hand of opportunity to reach back and let’s work on these things, and I think we have a lot of opportunity there," Nofire said.