Native Americans

Native Americans Revitalize Ancient Tattoo Traditions

For thousands of years, tattooing was an important form of cultural expression for Indigenous people across the Americas, but missionaries abolished the practice at different points in time as part of efforts to assimilate tribes and convert them to Christianity.

Today, a growing number of Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiians are reviving tattooing, using methods their ancestors developed millennia ago.

Jody Potts-Joseph was born and raised in the Yukon River village of Eagle, home of the Athabascan-speaking Han Gwich’in people.

“I was raised pretty old school on the land and learned our traditional way of life, hunting and fishing for subsistence,” she said. “I was 18 when I learned that historically, Gwich’in men and women got tattooed — men on their joints and wrists, and women on their faces — as a rite of passage.”

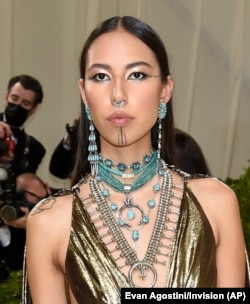

For years, Potts-Joseph wanted to have her chin marked, but the last Gwich’in tattoo artists had passed away. Her daughter, Quannah Chasinghorse, also wanted a tattoo.

“She was only 12 at the time, and I told her to wait,” Potts-Joseph said. “I wanted to make sure that she was in an emotional space where she could handle any possible criticism or backlash.”

After two years of praying on it, Potts-Joseph relented. Using a large ink-dipped sewing needle, she gave her daughter what are called Yidiiltoo — lines at her eyes and on her chin. Soon afterward, Potts-Joseph enlisted her then-16-year-old son Izzy to ink her chin.

“For me, it was a reclaiming of my identity and part of my resistance to the shaming of our people after colonization,” she said. “And I saw my daughter change — she came into her power. She found her voice. Tattooing is powerful medicine.”

Markers of identity, spirituality, rank

Cultural anthropologist Lars Krutak, author of “Tattoo Traditions of Native North America,” has studied the traditions in 30 countries.

As a University of Alaska Fairbanks graduate student, he spent time among Yupik elders living on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea. Yupik skin-stitch their tattoos, threading fine strands of reindeer or whale sinew through a bone or steel needle, then passing the thread through pigment and stitching designs into the top layer of skin.

“Typically, they used soot or lampblack from a seal oil lamp or the bottom of a cooking pot, mix it with water or human urine,” he said, explaining that urine’s high ammonia content helped in the healing process. “Sometimes, graphite was mixed into the pigment because it was believed to have spirit-repelling properties.”

Traditional tattooing served many functions.

“For one, marks could identify an individual’s family, clan, tribe or society,” Krutak said.

The Tlingit, Haida and other Northwest coastal peoples, for example, wore hand-poked family crests as a sign of social status, lineage and relationships to natural and supernatural events.

“There were therapeutic tattoos that were applied to primary joints to relieve arthritis,” he said. “I’ve documented tribes from Borneo to Alaska to Papua New Guinea who tattoo joint marks.”

Tattoos often marked milestones and achievements, such as a young hunter’s first kill.

“In some tribes in the Plains, you could read a man’s achievements on the battlefield by the marks he wore,” Krutak said.

Smithsonian anthropologists in the late 1880s reported that men of rank in the Omaha Tribe were given “honor marks,” charcoal tattoos applied with flint points bound to rattlesnake rattles.

A blind eye

Artist, writer and educator L. Frank Manriquez is descended from the Tongva and Acjachemen tribes of Southern California, which have seen a rebirth of traditional Indigenous tattooing.

“I’d thought about it for a long time,” Manriquez said. “For me, it was about the connection, a way to hold hands across time with my women ancestors.”

She was 40 years old when she got her first tattoo, from “a racist Chumash biker guy,” she said, laughing. He used a modern tattoo gun to ink parallel lines on her cheekbones.

Later, she had her chin tattooed with a traditional “triple 1” design. Later, Manriquez met Keone Nunes, who had studied traditional Polynesian tattooing in Samoa.

Nunes hand tapped Manriquez’s makapō, a black rectangle around her left eye — a design with roots in the Marquesas Islands of French Polynesia.

“Makapō literally means ‘blind,’” Manriquez said. “And what it means spiritually is that I can see what others cannot.”

Like Potts-Joseph in Alaska, Manriquez said tattoos have changed her life.

“Non-Native Californians started treating me as if I were wearing priest robes,” she said. “All of a sudden, I was something they could not understand. But Native Americans listen to me differently, treat me differently.”

‘Not a trend’

Tattooing, once considered the domain of sailors, inmates and carnival barkers, has gone mainstream in America. In January 2022, Rasmussen Reports found that half of all Americans under age 40 wore at least one tattoo, up from 38% in 2016.

Many non-Natives draw inspiration from — if not outright copy — traditional Indigenous tattoos, a fact that angers Potts-Joseph. Her daughter, Chasinghorse’s, modeling career exploded in 2020 after being featured in a Calvin Klein advertising campaign.

Since then, Chasinghorse has appeared on fashion runways, at galas on and magazine covers internationally. This has given her a platform to advocate for climate justice and Indigenous inclusion. But the exposure has come at a cost.

“I look on social media and I’m seeing non-Native men and women wearing Quannah’s exact markings,” Potts-Joseph said. “We are very much opposed to anyone outside of our culture wearing traditional tattoos.”

“This is our culture, our family, our ceremony,” she added. “This is not a trend.”

Native American News Roundup October 23-29, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

Tribal Leaders, Washington Officials to Meet in Late November Summit

The Biden administration announced its second Tribal Nations Summit November 30-December 1, designed to give tribal leaders and federal officials an opportunity to discuss issues and challenges Native American communities face today.

The White House announcement gave few additional details but promised further information later.

“The Summit will feature new Administration announcements and efforts to implement key policy initiatives supporting Tribal communities,” the statement said.

The first Tribal Nations Summit in November 2021 addressed the challenges of combatting the COVID-19 pandemic, Native American education and language revitalization, climate change, and treaty and land rights.

Read about the White House Tribal Nations Summit.

Feds File Discrimination Lawsuit Against South Dakota Hotel Owners

The U.S. Justice Department has sued the owners of a Rapid City, South Dakota, hotel, alleging that they violated the civil rights of Native Americans by trying to bar them from the property.

The complaint states that in March, Connie Uhre and her son Nicholas Uhre turned away Native Americans who sought to book a room at the Grand Gateway Hotel.

As VOA reported in March, Connie Uhre had also told other Rapid City hotel owners and managers that she did not want Native American customers there or in the hotel’s bar, Cheers. A post on her Facebook account said she cannot “allow a Native American to enter our business including Cheers.”

Uhre’s comments and actions, which followed a fatal shooting involving two teenagers at the hotel, sparked large protests in Rapid City and condemnation from the city’s mayor, Steve Allender.

Read more here.

The controversial and complex issue of Native American/Indigenous identity came up in two stories this week:

Native American Icon’s Identity Challenged

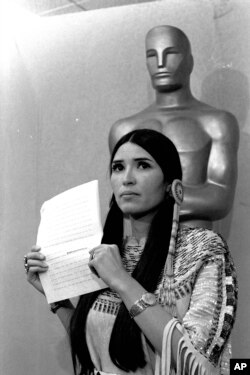

Sacheen Littlefeather, who spoke at the 1973 Oscars to reject actor Marlon Brando’s Best Actor Award, always identified herself as being of White Mountain Apache and Yaqui heritage and for decades before her death earlier this month, was a fierce activist for Native American rights.

Her biological sisters, Rosalind Cruz and Trudy Orlandi, however, say she was not Native American at all, according to an article in the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper. It also said that their sister’s long-standing claims of a childhood of poverty, abuse and neglect were untrue.

“Sacheen did not like herself. She didn’t like being Mexican,” one sister stated.

The article has sparked heated debate in social media circles about the complexities of Indigenous identity, an issue VOA has previously explored.

Read more here.

California Scholar Takes Back Native Identity Claims

A scholar who for decades claimed Native American identity has resigned her position with a leading Indigenous food sovereignty organization after backing down on long-standing claims of indigeneity.

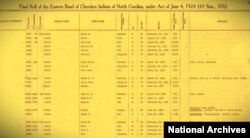

In a statement on her website, Elizabeth Hoover, a professor at the University of California, Berkley, and an expert in Native American environmental health and food sovereignty movements, said that after questions about her heritage were raised, she researched her genealogy and found no records of tribal citizenship “in the databases that were accessed.”

“Now, without any official documentation verifying the identity I was raised with, I do not think it is right for me to continue to claim to be a scholar of Mohawk/Mi’kmaq descent, even though my mother is insistent that she inherited this history for a reason,” she wrote.

The Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance is a nonprofit that promotes food security and food sovereignty in local, tribal, regional, national and international arenas.” The group Wednesday issued a statement accepting Hoover’s resignation as secretary of its leadership council.

Read more here.

State Recognized Tribes Hoping Outgoing Senators Can Win Them Federal Recognition

Two state-recognized Indian tribes are counting on a pair of retiring U.S. senators to help give them the federal recognition denied by the Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina has been a state-recognized Indian tribe since 1885, but the BIA has repeatedly denied them acknowledgement. In 1956, Congress passed legislation acknowledging them as “Indians” but denied them the services and benefits given to federally recognized tribes.

In 1997, the Bureau of Indian Affairs denied federal acknowledgment to the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians, saying they had failed to prove descent from a historical tribe. Alabama recognized them in 1979.

If tribes cannot gain recognition through the BIA, they have the option of turning to Congress to legislate on their behalf. Outgoing GOP Sen. Richard Shelby of Alabama is sponsoring legislation that, if passed, would recognize the MOWA Band; GOP Sen. Richard Burr of North Carolina is sponsoring similar legislation for the Lumbee Tribe.

Read more here.

Native American News Roundup Oct. 16-22, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

First Native American Woman in Space Addresses Native Media, Youth

Fighting the effects of low gravity, her feet tucked under a bar, NASA astronaut Nicole Mann answered questions from Indigenous media Wednesday during a live video interview moderated by The Associated Press.

Mann said she was overwhelmed at the view of planet Earth, “beautiful … delicate …and fragile” against the “blackest of black” backdrop of space.

Mann, who is a Wailacki member of the Round Valley Indian Tribes in Northern California, noted the diversity among crew members on the International Space Station.

“It just highlights … how incredible it is when we come together as a human species, the wonderful things we can … accomplish,” she said.

She also advised Indigenous youths that their dreams were possible.

“Stay committed and stay disciplined to your passions in life,” she advised. “Getting a good education is going to help open doors for you in the future.”

See her interview in full, below.

Government Takes Steps to Strengthen Relationship with Native Hawaiian Community

In an effort to further honor the federal government’s political and trust relationship with the Native Hawaiian community, the Interior Department on Tuesday announced it has drafted a set of policies and procedures designed to give the community a greater voice in federal decision-making.

Native Hawaiians will have a chance to comment on the proposed consultation policy during virtual meetings in November and December.

“The Interior Department is committed to working with the Native Hawaiian community on a government-to-sovereign basis to address concerns related to self-governance, Native Hawaiian trust resources and other Native Hawaiian rights,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said. “A new and unprecedented consultation policy will help support Native Hawaiian sovereignty and self-determination as we continue to uphold the right of the Native Hawaiian community to self-government.”

The U.S. government acknowledges Native Hawaiians as “a distinct and unique Indigenous people with a historical continuity to the original inhabitants” of Hawaii. But Congress has never formally recognized them as it has 574 Native American tribes and nations, and Native Hawaiians have never established a formal government.

For more background on the issue, click here: https://www.voanews.com/a/native-hawaiians-divided-on-federal-recognition/4775275.html

Native Leaders Address Upcoming Supreme Court Review of ICWA

Tribal leaders from the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, the Morongo Band of Mission Indians in California, and the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin, along with a group of legal experts, held a joint press briefing on Monday to discuss the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), a 43-year-old federal law designed to prevent, wherever possible, Native American children from being removed from families and communities and placed in non-Native families and institutions.

On November 9, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear the case of Brackeen v. Haaland, a lawsuit that argues that ICWA imposes restrictions based on race, not in the best interests of Indian children, and is an attempt by the government to intrude on matters states should decide.

“It is stunning that there are those who seek to overturn a wildly successful law like ICWA, including by states with serious issues in their own child welfare systems, against the warnings of these experts who dedicate their careers and lives to helping children,” Oneida Nation chairman Tehassi Hill said.

In a written statement, Cherokee Nation chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. called the case a “serious effort to twist the basic truth” around ICWA and principles of Indian law that recognize tribes as sovereign nations.

The participants in the briefing suggested that overturning ICWA could lead to challenges to tribal sovereignty on a host of other matters, including natural resource management and casino gaming.

See full briefing, click here.

KU Students Demand Accounting for Storage of Native American Remains

Student groups at the University of Kansas are calling on university officials to apologize and explain why Indigenous human remains and funerary artifacts have been stored in the same academic building in which the school’s Indigenous studies program is housed.

They also called for the school to hold a public press conference to apologize for not disclosing details.

On September 20, KU became the latest U.S. institution to acknowledge that it has Native American remains, funerary and other sacred objects in its possession. The announcement comes 32 years after passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which sets out criteria for tribal nations to reclaim ancestral remains and other sacred objects.

“In keeping with NAGPRA and the values of our institution, KU will continue to facilitate prompt, respectful and culturally appropriate repatriation efforts that include NAGPRA protocols,” the university said in an update this week.

First Native American Woman in Space Awed by Mother Earth

The first Native American woman in space said Wednesday she is overwhelmed by the beauty and delicacy of Mother Earth and is channeling "positive energy" as her five-month mission gets underway.

NASA astronaut Nicole Mann said from the International Space Station that she's received lots of prayers and blessings from her family and tribal community. She is a member of the Wailacki of the Round Valley Indian Tribes in Northern California.

Mann showed off the dream catcher she took up with her, a childhood gift from her mother that she's always held dear. The small traditional webbed hoop with feathers is used to offer protection, and she said it's given her strength during challenging times. Years before joining NASA in 2013, she flew combat in Iraq for the Marines.

"It's the strength to know that I have the support of my family and community back home and that when things are difficult or things are getting hard or I'm getting burned out or frustrated, that strength is something that I will draw on to continue toward a successful mission," Mann told The Associated Press, which gathered questions from members and tribal news outlets across the country.

Mann said she's always heeded her mother's advice on the importance of positive energy, especially on launch day.

"It's difficult for some people maybe to understand because it's not really tangible," she said. "But that positive energy is so important, and you can control that energy, and it helps to control your attitude."

Mann, 45, a Marine colonel and test pilot who was born in Petaluma, California, said it's important to recognize there are all types of people aboard the space station. It's currently home to three Americans, three Russians and one Japanese astronaut.

"What that does is it just highlights our diversity and how incredible it is when we come together as a human species, the wonderful things that we can do and that we can accomplish," she said.

While fascinated with stars and space as a child, Mann said she did not understand who became astronauts or even what they did.

"Unfortunately, in my mind at that time, it was not in the realm of possibilities," she said.

Now, she's taking in the sweeping vistas of Earth from 260 miles (420 kilometers) up and hoping to see the constellations as she encourages youngsters to follow their dreams.

As for describing Earth from space, "the emotions are absolutely overwhelming," she said. "It is an incredible scene of color, of clouds and land, and it's difficult not to stay in the cupola (lookout) all day and just see our planet Earth and how beautiful she is, and how delicate and fragile she is against the blackest of black that I've ever seen — space — in the background."

Mann rocketed into orbit with SpaceX on October 5. She'll be up there until March. She and her husband, a retired Navy fighter pilot, have a 10-year-old son back home in Houston.

The first Native American in space, in 2002, was now-retired astronaut John Herrington of the Chickasaw Nation.

Native Americans Recall Torture, Hatred at Boarding Schools

After her mother died when Rosalie Whirlwind Soldier was just 4 years old, she was put into a Native American boarding school in South Dakota and told her native Lakota language was "devil's speak."

She recalls being locked in a basement at St. Francis Indian Mission School for weeks as punishment for breaking the school's strict rules. Her long braids were shorn in a deliberate effort to stamp out her cultural identity. And when she broke her leg in an accident, Whirlwind Soldier said she received shoddy care leaving her with pain and a limp that still hobbles her decades later.

"I thought there was no God, just torture and hatred," Whirlwind Soldier testified during a Saturday event on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation led by U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, as the agency confronts the bitter legacy of a boarding school system that operated in the United States for more than a century.

Now 78 and still living on the reservation, Whirlwind Soldier said she was airing her horrific experiences in hopes of finally getting past them.

"The only thing they didn't do was put us in (an oven) and gas us," she said, comparing the treatment of Native Americans in the U.S. in the 19th and 20th centuries to the Jewish Holocaust during World War II.

"But I let it go," she later added. "I'm going to make it."

Saturday's event was the third in Haaland's yearlong "Road to Healing" initiative for victims of abuse at government-backed boarding schools, after previous stops in Oklahoma and Michigan.

Starting with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the U.S. enacted laws and policies to establish and support the schools. The stated goal was to "civilize" Native Americans, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians, but that was often carried out through abusive practices. Religious and private institutions that ran many of the schools received federal funding and were willing partners.

Most closed their doors long ago and none still exists to strip students of their identities. But some, including St. Francis, still function as schools — albeit with drastically different missions that celebrate the cultural backgrounds of their Native students.

Former St. Francis student Ruby Left Hand Bull Sanchez traveled hundreds of kilometers from Denver to attend Saturday's meeting. She cried as she recalled almost being killed as a child when a nun stuffed lye soap down her throat in response to Sanchez praying in her native language.

"I want the world to know," she said.

Accompanying Haaland was Wizipan Garriott, a Rosebud Sioux member and principal deputy assistant secretary for Indian affairs. Garriott described how boarding schools were part of a long history of injustices against his people that began with the widespread extermination of their main food source — bison, also known as buffalo.

"First they took our buffalo. Then our land was taken, then our children, and then our traditional form of religion, [and] spiritual practices," he said. "It's important to remember that we Lakota and other Indigenous people are still here. We can go through anything."

The first volume of an investigative report released by the Department of the Interior in May identified more than 400 boarding schools that the federal government supported beginning in the late 19th century and continuing well into the 1960s. It also found at least 500 children died at some of the schools, although that number is expected to increase dramatically as research continues.

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition says it's tallied about 100 more schools not on the government list that were run by groups such as churches.

"They all had the same missions, the same goals: 'Kill the Indian, save the man,'" said Lacey Kinnart, who works for the Minnesota-based coalition. For Native American children, Kinnart said the intention was "to assimilate them and steal everything Indian out of them except their blood, make them despise who they are, their culture, and forget their language."

South Dakota had 31 of the schools including two on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation — St. Francis and the Rosebud Agency Boarding and Day School.

The Rosebud Agency school, in Mission, operated through at least 1951 on a site now home to Sinte Gleska University, where Saturday's meeting happened.

All that remains of the boarding school is a gutted building that used to house the dining hall, according to tribal members. When the building caught fire about five years ago, former student Patti Romero, 73, said she and others were on hand to cheer its destruction.

"No more worms in the chili," said Romero, who attended the school from ages 6 to 15 and said the food was sometimes infested.

A second report is pending in the investigation into the schools launched by Haaland, herself a Laguna Pueblo from New Mexico and the first Native American Cabinet secretary. It will cover burial sites, the schools' impact on Indigenous communities and try to account for federal funds spent on the troubled program.

Congress is considering a bill to create a boarding school "truth and healing commission," like one established in Canada in 2008. It would have a broader scope than the Interior Department's investigation into federally run boarding schools and subpoena power, if passed.

Native American News Roundup Oct. 9-15, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

Americans Remain Divided Over Columbus-Indigenous Peoples Holiday

For nearly 90 years, the U.S. has observed the second Monday in October as Columbus Day in honor of explorer Christopher Columbus who in 1492 stumbled across the Caribbean Islands.

Growing numbers of U.S. states, localities and institutions have renamed the holiday Indigenous Peoples or Native American Day.

For the second year in a row, President Joe Biden proclaimed the Monday holiday as Indigenous Peoples Day to “honor the sovereignty, resilience, and immense contributions that Native Americans have made to the world” and recommitting the federal government to upholding "its solemn trust and treaty responsibilities to Tribal Nations.”

To read more, click here: A Proclamation on Indigenous Peoples’ Day, 2022

VOA reporter Genia Dulot was in Los Angeles, California, Monday, and had this report on how tribes in Southern California marked the day.

Governors of two U.S. states were criticized by conservative commentators for actions related to the holiday.

New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, the first Democratic Hispanic woman to become a U.S. governor, rescinded four proclamations issued in the 1800s as federal troops fought against resistance by Southwestern tribes. [[ / ]] Conservative media accused her of erasing history.

“No context whatsoever was given about the full content of the proclamations other than her characterization of them,” a writer complained in an editorial in the Piñon Post, a conservative New Mexican newspaper.

South Dakota, where there are nine federally-recognized Tribes, has been celebrating Native American Day since 1989. But when Republican Governor Kristi Noem acknowledged the holiday on Twitter, she was scolded by a Washington Examiner commentator who suggested she had sold out to “Dangerously radical, left-wing cultural Marxists.”

“South Dakota's Native American history is a noble history of a proud people,” the editorial read. “No rational human being should have any objection to celebrating their heritage. But there are 364 other days in the year for that. Encroaching on Columbus Day under the guise of appreciating Indigenous culture is done only because of the Left's hatred for our culture and history.”

To read more, click here: Kristi Noem chose to acknowledge Native American Day instead of Columbus Day

Biden Announces Protections for Iconic Sites in Colorado

President Biden on Wednesday designated a new national monument in Colorado as part of his administration's pledge to “protect, conserve and restore” iconic and historical sites across the U.S.

“This action will honor our nation’s veterans, Indigenous people, and their legacy by protecting this Colorado landscape, while supporting jobs and America’s outdoor recreation economy," the White House said in announcing the proclamation.

The Camp Hale-Continental Divide National Monument sits at 2,800 meters in the Rocky Mountains in what was once part of the Ute and other tribes’ ancestral homelands. The camp was built in 1942 to train Army ski troopers during World War II and housed German prisoners of war and their suspected sympathizers.

The White House also announced a proposed 20-year withdrawal of federal oil, gas and mineral leases on approximately 91,000 hectares in the Thompson Divide in Colorado’s White River National Forest. Preexisting leases in the area would not be included in the withdrawal.

To read more, click here: President Biden designates Camp Hale – Continental Divide National Monument

Massachusetts Museum to Return Wounded Knee Artifacts to Lakota Descendants

A small museum in one of Massachusetts’ oldest villages announced this week that it will return more than 150 Lakota artifacts to the Oglala Lakota tribe of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, including items that were looted from the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre.

Barre Museum Association President Ann Meilus announced the items’ return during a virtual press event at the town’s library.

Lakota from Pine Ridge and the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota have lobbied for 30 years to have the items returned, most recently with the assistance of Vermont artist/journalist Mia Feroleto, who is a friend of Chief Henry Red Cloud, a fifth generation descendant of Lakota warrior and diplomat Red Cloud.

Why did it take so long?

“I’ll be honest,” Meilus said. “We had interference from third parties that created an atmosphere of distrust. We are a volunteer organization. … It was hard for a lot of the older members to see that they needed to do the right thing.”

Oglala Sioux President Kevin Killer called the announcement a good step.

“But I'm sure there's more steps that need to be followed,” he added.

To read more, click here: After 130 years, Massachusetts Museum will return sacred Lakota artifacts

Proposed Changes to NAGPRA up For Public Comment

After consulting with dozens of Native American, Alaskan and Hawaiian tribes and organizations, the U.S. Interior Department has proposed changes to the 1990 law requiring museums and federal agencies to identify and inventory Native American human remains, burial items, and artifacts of spiritual and cultural significance and work to return them to tribes and lineal descendants.

In a press release Thursday, the federal agency said proposed changes to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act would streamline and make more transparent the inventory process and give Tribes and Native Hawaiian groups a greater role in the process of repatriating items to lineal descendants and tribal communities.

To read more, click here: Interior Department takes next steps to update Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

Native American News Roundup Oct. 2-8, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

Haaland Announces Expansion of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland announced an expansion of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site during a solemn ceremony there Wednesday.

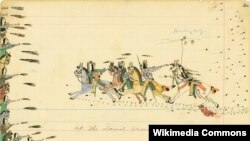

Haaland, a citizen of the Laguna Pueblo, was joined by National Park Service Director Chuck Sams, a member of the Cayuse and Walla Walla tribes, at the site where Colorado cavalry charged a Cheyenne and Arapaho encampment in November of 1864, killing an estimated 200 people, more than half women, children and the elderly.

“It is our solemn responsibility at the Department of the Interior, as caretakers of America’s national treasures, to tell the story of our nation,” Haaland said. “We can't rely on history books that were written by those who colonized these lands to remember these stories. We must invest in opportunities like this that offer the chance for true and honest dialogue straight from survivors and their descendants.”

Her announcement to expand the site by an additional 1,400 hectares did not satisfy everyone at the event. Northern Cheyenne Sacred Hat keeper Michael Bearcomesout suggested the additional land could be used to build a university or a retirement center.

“We’re here all day listening to people talk about saving this site so that we remember,” Bearcomesout said. “But not once did we hear anything about paying back the Cheyenne and Arapaho people for what happened here.”

To watch a NPS video about the massacre, click here.

Secretary Haaland commits to telling America’s story at Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

Native American Astronaut Nicole Mann Arrives at Space Station

A beaming – and weightless – Nicole Aunapu Mann arrived at the International Space Station Thursday as it flew 420 kilometers above the west coast of Africa. A Wailacki citizen of the Round Valley Indian Tribes in Northern California, she made history as the first Native American woman to leave the earth’s atmosphere.

Mann launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida Wednesday, commanding a crew of three others – Josh Cassada from the United States, Koichi Wakata from Japan and Anna Kikina from Russia.

"Awesome!" said Mann as they reached orbit aboard the SpaceX Dragon Endurance spacecraft. "That was a smooth ride uphill. You've got three rookies who are pretty happy to be floating in space right now."

Mann and her crew will replace three Americans and one Italian who will return in their own SpaceX capsule next week after almost half a year aboard the space station. Until then, 11 people will share the orbiting lab.

NASA has announced that The Associated Press, on behalf of Native American media affiliates, will conduct an in-flight interview with Mann on October 19.

SpaceX delivers Russian, Native American women to station

Lakota Culture Bearer Kevin Locke Remembered

Family and friends gathered in the Black Hills of South Dakota Friday to celebrate the life of Kevin Locke, also known as Tokeya Inajin (“The First to Rise”), who died September 30 from a severe asthma attack.

A Hunkpapa Lakota - Anishinaabe culture bearer from the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, Locke achieved fame for his North American Indigenous flute playing and his “Hoop of Life,” a traditional hoop dance that celebrated the unity of humankind.

In the 1980s, Locke became a follower of the Baha’i Faith, which he believed aligned with traditional Lakota spirituality.

“I saw people from all over the world, from widely diverse backgrounds, recognizing the need to unite and to come together based upon our spiritual reality as human beings, and recognizing the global dimensions of the human family,” he explained on his website. “Then, in 1983, some Baha’i friends from the Indigenous nations of South America visited our Standing Rock Reservation, and they helped me grow in the work to foster an awareness of our one human family.”

Locke worked with The Lakota Language Consortium and The Language Conservancy as part of an urgent effort to preserve and revitalize the Lakota language.

Rapid City resident Marina Allison, an Oglala Lakota member of the Cheyenne River Tribe, remembers listening to Locke and her mother speak Lakota.

“I feel we are losing a valuable teacher and mentor in Lakota/Dakota/Nakota country,” she told VOA. “I and many others will remember his teachings. ‘May he rest in power as a common man,’ as we say. Wopila pilamiya — great thanks.”

‘Huge loss for the world’: Lakota cultural bearer Kevin Locke passes on

- By Reuters

Sacheen Littlefeather, Who Declined Oscar on Marlon Brando's Behalf, Dies at 75

Native American actress and activist Sacheen Littlefeather, who declined the best-actor award on behalf of Marlon Brando during an Oscars protest in 1973, has died aged 75, the motion picture Academy said on Monday.

Littlefeather, who the Hollywood Reporter said died at her home in California on Sunday surrounded by loved ones, was catapulted to fame when her friend Brando boycotted the 45th Oscars ceremony over what he viewed as the stereotypical portrayal of Native Americans in films and on television.

Taking to the stage in a traditional buckskin dress to refuse the Oscar — awarded for Brando's portrayal of Vito Corleone in "The Godfather" — in his stead, she gave a critical speech on the same issue, also drawing attention to a protest at Wounded Knee, South Dakota against the mistreatment of American Indians.

She was booed off for her remarks and boycotted by the film industry for decades.

This year Littlefeather, who had been diagnosed with breast cancer, received a belated apology letter from then-Academy president David Rubin, and last month the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures held an event in her honor.

"I was representing all indigenous voices out there, all indigenous people, because we have never been heard in that way before," she said, reflecting on what happened in 1973.

Native American News Roundup September 25 – Oct. 1, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

White House: We Should Listen to Native Americans on Mascots

President Joe Biden welcomed the Atlanta Braves baseball team to the White House Monday, where he praised them for an “unstoppable, joyful” win in the 2021 World Series. The president made no mention of the longstanding controversy over the team’s name.

Under pressure from Native American groups, the football team formerly known as the “Washington Redskins” changed its name to the Commanders, and other professional, collegiate and secondary school teams have followed suit.

But the Atlanta Braves have said their brand, which includes a tomahawk logo on their jerseys, will remain. So, too, will the so-called “tomahawk chop,” in which spectators hack at the air and sing a “war chant” rooted in a 1950s children’s cartoon show that stereotyped Indians.

Later Monday, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said Biden believed all people deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.

“We should listen to Native American and Indigenous people who are most impacted by this,” she said.

Her remarks drew criticism from the Washington Examiner newspaper.

“Teams named themselves after American Indians because of their bravery and nobility,” the commentator wrote. “Ironically, the liberal idea of treating Native Americans with ‘dignity and respect’ on this issue is to ignore them and erase them from our culture entirely.”

Haaland: Slur Denied Humanity of Generations of Native Women

“Words matter,” U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland wrote in The Washington Post Wednesday, explaining the erasure of a derogatory term for Indigenous women from the names of nearly 650 federal locations and land features.

“The word is squaw — a term so offensive that I have never used it except in issuing the order to make the name change, and beyond this sentence I will not repeat it here or anywhere,” she wrote.

“It was stolen from the word for ‘woman’ in one specific Indigenous language, I believe Algonquian. The word was then perverted — as so many Indigenous words and customs were — turning it into a broad racial slur, a caricature that removed individual identity and dignity from all women of Native American heritage.

“The insidious result was to deny the humanity of generations of Native wives, daughters and mothers, as if using cheap slang would make the victims somehow deserving of assault — even to this day.”

Haaland cited disproportionate rates of violence against Native women as evidence that persecution of Indigenous women continues.

“The search for justice for these crimes has been underfunded for decades, leaving many — including me — to believe that these crimes are somehow tragically seen as less worthy of investigation.”

Changing geographic names, she said, was one way to affirm the value of Indigenous women and ensure that public lands and waters are “accessible and welcoming.”

Prominent MMIW Justice Seeker Sues Federal Government Alleging BIA Police Abuses

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in North Dakota this week filed a lawsuit against the federal government, alleging that Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) police on the Standing Rock Reservation “assaulted, humiliated and dehumanized” a well-known champion of justice for missing and murdered Indigenous men and women.

As VOA reported in 2019, the plaintiff, Lissa Yellowbird-Chase, is an enrolled member of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation who in 2015 founded the Sahnish Scouts, a citizen-led group that works to locate the missing, find remains, and give support to victims’ families.

Yellowbird-Chase alleges that in February 2021, while driving a rescued trafficking victim to safety, county law enforcement stopped her for speeding. Because she possessed a quantity of marijuana, they turned her over to BIA officers, who handcuffed her and transported her to the Standing Rock Detention Center. There, the lawsuit states, male officers forced her to strip to her underwear publicly, then privately performed a body cavity search and subjected her to lewd comments. The suit also alleges that BIA officers robbed Yellowbird-Chase of more than $800 and her prescription medication.

The BIA-OJS Corrections Handbook states:

“…The arrestee(s) … will be un-cuffed and directed to a designated private area, where a strip search will be conducted by a staff member of the same gender, if possible. In the case of female arrestees, a staff member of the same gender is required. If a female staff member is not available, the female arrestee will be returned to the admissions area and placed in a holding cell. A female trained in conducting strip searches will be summoned and upon arrival the female arrestee will be processed.”

In September 2021, Yellowbird-Chase filed a Federal Tort claim against the Interior Department; in May 2022, the Interior Department denied her claim.

The U.S. Federal Tort Claims Act allows individuals to sue the federal government and seek monetary damages.

What happened to Yellowbird-Chase is “shameful and reprehensible,” said Stephanie Amiotte, ACLU of North Dakota legal director. “The emotional and physical distress these officers inflicted upon Lissa is severe, traumatizing and could only be born out of a fundamental disregard for her humanity and abuse of power by law enforcement officers. Our government should not treat people this way.”

VOA reached out to the BIA for comment.

“The Bureau of Indian Affairs does not comment on ongoing litigation," a spokesperson said in an emailed statement.

Additional Tribes Given Access to Crime Information Sharing Systems

Sixteen federally recognized Native American Tribes have been added to the U.S. Justice Department’s Tribal Access Program (TAP), gaining access to national crime information databases.

TAP will provide and train tribes to use kiosk workstations to take fingerprints and mugshots and search and submit information to the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division.

“The Department is committed to strengthening our government-to-government partnership with tribal nations, including providing critical access to criminal databases through the Tribal Access Program,” U.S. Deputy Attorney General Lisa O. Monaco said Tuesday. “With today’s announcement, 16 additional participating tribes will be able to register sex offenders, protect victims of domestic violence, prevent prohibited persons from obtaining firearms, and help locate missing people.”

Lack of access to federal databases has been blamed, in part, for a high number of unsolved missing and murder cases in Indian Country. The Justice Department in 2015 engaged nine tribes in a two-year pilot study, adding members incrementally ever since.

Tuesday’s announcement means a total of 123 tribes, comprising 450 tribal government agencies, are now able to access and share nationwide information on missing persons, sex offenders, criminals and fugitives; conduct background and fingerprint checks including those unrelated to crime, such as screening prospective employees or child care workers.

Telework Not an Option for Many Native Americans

The COVID-19 pandemic set off a radical shift in the way most Americans go to work. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that as of July 2022, about one quarter of all employed Americans worked from home at least one day a week because of COVID-19.

A 2020 study by the Brookings Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, showed that telework “can help employers afford the cost of hiring high-skill labor, and keep these workers connected to the office and each other no matter where they’re based. Telework also allows employers access to a larger group of potential workers and, in turn, allows workers access to more job options.

Rob Maxim, a researcher at the Brookings Institution and a citizen of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe in Massachusetts, teamed up with Matt Gregg, an economist for the Center for Indian Country Development at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, to analyze census data from IPUMS USA.

They found that working from home is less of an option for Native Americans than for other racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.

At the height of the COVID-19 economic crisis of 2020, Native Americans teleworked at a rate 8 percentage points lower than white workers. That gap closed somewhat as workers began returning to the office in 2021 and 2022, but by early summer 2022, Native Americans were teleworking at a rate 2 percentage points lower than white workers.

The study blames, in part, gaps in education and employment opportunities. Previous studies have shown that one-third of all Native American workers are employed in front-line industries such as health care, education, or grocery or convenience stores, where teleworking is not an option.

Housing conditions and restricted access to the internet and other necessary technology also impedes Native Americans from joining the telework “revolution.”

“For Native nations, remote work has the potential to bring new economic opportunity,” the authors write. “This matters, because Native nations differ from many other communities in that out-migration not only has economic impacts but is also a threat to cultural well-being.”

The study suggests the federal government should step up economic development and education on tribal lands; it should also work to give “urban Indians” access to the kinds of jobs that are more likely to offer telework as an option.

Cherokee Leader Looks to Boost Support of Cherokee Artists

Acknowledging the devastating economic impact that COVID-19 has had on Cherokee artists, Cherokee Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. has proposed a program like President Franklin Roosevelt’s Federal Art Project of the 1930s and 1940s, through which the government helped painters, sculptors and other visual artists recover from the devastating financial impacts of the Great Depression.

“From time immemorial, artistic expression by Cherokees reflects who we are as a distinct people, our connection to the spiritual world, our deepest concerns and our highest aspirations,” Hoskin Jr. wrote in a guest opinion for Native News Online. “To ensure that Cherokee culture remains strong and vibrant far into the future, we need to get behind our artists today.”

If approved, the Cherokee Artist Recovery Act would allot $3 million to the Cherokee art community over three years to purchase works of art, fund art education, upgrade arts facilities and help artists market their work.

Minnesota Ojibwe Harvest Sacred, Climate-Imperiled Wild Rice

Seated low in her canoe sliding through a rice bed on this vast lake, Kendra Haugen used one wooden stick to bend the stalks and another to knock the rice off, so gently the stalks sprung right back up.

On a mid-September morning, no breeze ruffled the eagle feather gifted by her grandmother that Haugen wore on a baseball cap as she tried her hand at wild rice harvesting — a sacred process for her Ojibwe people.

"A lot of reservations are struggling to keep rice beds, so it's really important to keep these as pristine as we can. ... It renews our rice beds for the future," the 23-year-old college student said.

Wild rice, or manoomin (good seed) in Ojibwe, is sacred to Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes region, because it's part of their creation story — and because for centuries it staved off starvation during harsh winters.

"In our origin story, we were told to go where food grew on water," said Elaine Fleming, a Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe elder whose manoomin class at Leech Lake Tribal College went harvesting last week. "It's our sacred food."

But changing climate, invasive species and pollution are threatening the plant even as its cultivated sibling rises in popularity nationwide as an exceptionally nutritious food, though often priced out of reach of urban Indigenous communities.

Those threats make it crucial to teach young band members to harvest wild rice respecting both rituals and the environment. That will help wild rice remain available as an essential element for ceremonies, but also as a much-needed income generator for the Leech Lake reservation, where nearly 40% of Native residents live in poverty.

The basic instructions for newbies reflect that dual reality — respect the rice by not breaking the stems, and if you lose balance, jump out to avoid tipping the canoe with its precious cargo.

Fleming gave everyone tobacco from a zip-close bag. Before scattering it on the calm water and setting out, the youths gathered around another elder praying in Ojibwe — to introduce the group to the natural elements around them, explain why it needed their help, ask for safe passage on the water and give thanks.

"Any time you take something from the earth, you want to thank the earth for what she's given us," said Kelsey Burns, a student and first-time ricer.

That reciprocity between humans and nature is essential to Ojibwe spirituality. In their stories, the Creator, before bringing to the earth Anishinaabe, the first Indigenous person, gathered all animals to ask how they could help.

"Plants were listening and chimed in and said, 'We have gifts too, so Anishinaabe can have a good life,'" Fleming explained. "Rice said, 'We'll feed Anishinaabe.'"

In two hours on the water, the pairs of polers, who stood steering with 20-foot poles, and knockers, who rained rice into the canoe until it formed a thick, green-brown carpet, gathered about 35 pounds. Experienced ricers can harvest a quarter ton a day.

This year, they can get $6 per pound of rice, a high price because the two-week harvest is particularly meager, said Ryan White. A 44-year-old single dad, he takes his two boys and a nephew ricing to help cover the bills and for the kids to buy video games.

"You learn the essence of hard work out here," he said while knocking rice on a recent afternoon, with duct tape over his trousers' hem and shoes so not a grain would be wasted.

"Cleaning the boat real good," White explained later as he swiped the rice into a sack. "Because of stories we heard of old times, when … even a handful like this meant a meal or two for the kids, and at the end of winter it actually might save your family."

"That manoomin is our brother, that saved us as a people many different ways," said Dave Bismarck, who was loading about 200 pounds of just-harvested rice at a nearby landing. "Ricing to me is real spiritual. There's a lot who have gone home already, and when I'm ricing, the harder I work … the closer I am to them."

But the beds are "continually shrinking," said White, who's been ricing for three decades. And that endangers wild rice's spiritual and economic gifts.

While some natural cycling is normal, bad years for wild rice are becoming more frequent, said Ann Geisen, a wildlife lake specialist with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

"It seems to be tied to climate change," she added. "Bigger storm events when it's uprooted and wiped out, we seem to have more of these. A big bounce (in water levels) in the spring can wipe out an entire lake."

A warming climate can also damage the plant, whose seeds need to be close to freezing on shallow lake bottoms for months to germinate well, and brings destructive invasive species and fungi to Minnesota, Wisconsin and parts of Canada, wild rice's only natural habitats.

"It's going to completely ravish natural stands," said Jenny Kimball, a professor of agronomy and plant genetics at the University of Minnesota. She works on both conservation and developing more resistant breeds for cultivated wild rice growers, an industry she estimates adds about $58 million to the state economy and has far outpaced natural production for decades.

Most Ojibwe bands want to save natural stands, however, and several recently filed lawsuits fighting water contamination — including one dismissed this year in White Earth tribal court that named manoomin as the lead plaintiff in a novel "rights of nature" approach.

The suit accused the state of failing to protect water where wild rice grows by allowing the pumping of billions of gallons of groundwater from an oil pipeline project.

In July, two other northern Minnesota tribes sued the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency over its approval of state changes to water quality standards that the tribes allege would increase pollution and damage wild rice.

Leech Lake students and faculty discussed industrial pollution and controversial pipelines as they gathered outside the college for a feast celebrating their first day harvesting.

Before cooking the rice, they had to parch it, stirring it in a giant iron kettle for more than an hour; jiggle the husks loose by dancing over it as it lay in a hide-covered hole in the ground; and finally winnow it in birchbark baskets.

"We understand our responsibility, as nation, to this land. We're supposed to think seven generations to the future," Fleming said.

Burns, the student, was thinking of her son, who's 5.

"I like learning everything that I can about our culture," she said. "I didn't learn much when I was younger, so I felt a part of me was missing. I want to keep teaching everything I learn."

Native American News Roundup September 11-17, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

First Native American Treasurer Sworn into Office

Mohegan Chief Marilynn “Lynn” Malerba is the first Native American treasurer of the United States.

“We all know that, historically, many promises have not been kept to the indigenous peoples of this nation. But we can and will do better,” Malerba said at Monday’s White House swearing-in. “My appointment is a promise kept.”

In prepared remarks, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called Malerba’s appointment a signal of the Biden administration’s “respect for, and commitment toward, our nation-to-nation relationship, trust and treaty responsibilities, and Tribal sovereignty and self-determination.”

Malerba’s signature will now appear on U.S. currency alongside Yellen’s.

President Joe Biden appointed Malerba U.S. treasurer in June and gave her oversight of a new Office of Tribal and Native Affairs at the Treasury Department, which will work to help strengthen tribes’ economies.

“This office will serve as a hub for Treasury’s portfolio of issues related to Indian Country,” Yellen said. “It will lead Treasury’s nation-to-nation diplomacy on issues regarding the economic security of tribal nations. It will provide expertise internally across policy offices and bureaus and push for increased interagency collaboration and cooperation on tribal economic development.”

In October 2021, the Government Accountability Office found that the Treasury Department “faced challenges” distributing more than $8 billion in certain COVID-19 relief funds for tribes.” The GAO said Treasury had relied on inaccurate population data to make payments and had failed to consult tribes prior to those payments, recommending that Treasury update its tribal consultation policies.

Malerba sworn in as 1st Native American in US Treasurer post

Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez congratulated Malerba on her appointment as Treasurer and sent a message in Diné and in English to citizens of the nation he leads.

He joined Cabinet members, lawmakers and other officials at the White House Tuesday to celebrate passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, a $430 billion bill that allocates $720 million to tribes to help them take action against the effects of climate change.

“The Navajo Nation has a seat at the table with President Biden and his administration,” said Nez, according to the Indian Gaming website. “The American Rescue Plan Act delivered over $2 billion to the Navajo Nation, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is delivering millions more, and now the Inflation Reduction Act will help our people with drought mitigation, clean energy initiatives, lower prescription costs, and much more.”

While in Washington, Nez also met with Environmental Protection Agency officials, calling for expanded efforts to clean up waste from hundreds of abandoned uranium mines on Navajo land. Between 1944 and 1986, the federal government and its contractors extracted nearly 30 million tons of uranium ore from Navajo lands, leaving behind radioactive waste and other dangerous contaminants, including arsenic, copper, nickel, and selenium.

Commerce Department Grants Nevada Tribe More Than $5 million to Improve Water System

U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo says her department’s Economic Development Administration (EDA) is granting $5.2 million to the Walker River Paiute Tribe in Schurz, Nevada, to help boost economic growth by improving the tribe’s water system.

The funds will support replacing and expanding four water mains and installing 45 fire hydrants, the lack of which previously limited commercial development. This EDA investment will be matched with $156,674 in local funds and is expected to create or retain 25 jobs.

“President Biden is committed to supporting tribal communities in their recovery from the coronavirus pandemic,” said Raimondo. “This EDA investment will provide more secure water system infrastructure to the Walker River Indian Reservation, improving economic resilience and creating the potential for business growth and expansion.”

The Desert Research Institute and the Guinn Center for Policy Priorities, both based in Nevada, recently published findings of a joint study assessing water security in Native American homes and communities in Nevada.

Analyzing U.S. Census Bureau data on the availability of safe, hot and cold running water, flush toilets and baths and/or showers, researchers found that between 1990 and 2019, an average of 0.67 percent of Native American households in Nevada lacked complete indoor plumbing -- higher than the national average of 0.4 percent.

In 2019, study authors say more than 20,000 Native Americans in Nevada were “plumbing poor.”

"Previous studies have found that Native American households are more likely to lack complete indoor plumbing than other households in the U.S., and our results show a similar trend here in Nevada," said study author Erick Bandala. "This can create quality of life problems, for example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when lack of indoor plumbing could have prevented basic health measures like hand-washing."

Bandala blamed population growth, climate change and water rights.

Tribes in South Dakota Agree to Buy Wounded Knee Site

A highly symbolic parcel of land on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota could soon pass back into Native hands.

The Oglala Lakota and Cheyenne River tribes have agreed to purchase 16 hectares of land at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Long owned by non-Natives, it is close to the site where the 7th U.S. Cavalry slayed scores of Lakota men, women and children in 1890.

The Oglala Lakota tribe said it would pay $255,000 of the $500,000 purchase price, and the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, whose Miniconjou ancestors under Chief Spotted Tail comprised most of the massacre victims, would pay $245,000.

The tribes will petition the U.S. Department of the Interior to hold the land in trust and allow it to remain undeveloped, as a permanent memorial to those who died.

Why must a tribe buy land on its own reservation, only to turn it over to the government?

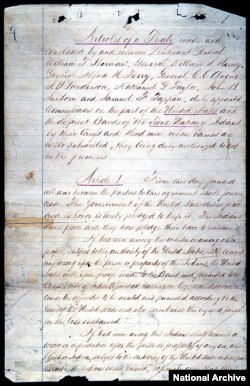

The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty set aside all of the land west of the Missouri River as the “Great Sioux Reservation,” to be held in common by tribes. But in 1887, Congress authorized the president to break up reservation land into small parcels which were distributed to tribe members who registered on tribal rolls. Members did not own the land outright, however; the government held it in trust for their use. Land left over after those allotments was sold or leased to non-Native settlers.

Who originally purchased the Wounded Knee site is not clear. The settlement was first named Brennan, after a federal agent who supervised the reservation from 1899 to 1917, according to a 1951 article in the Argus-Leader (Sioux Falls, SD) newspaper.

In 1918, a man by the name of Roy Thomas built a trading post there, which remained in operation through two more owners before its destruction in the 1973 American Indian Movement occupation of Wounded Knee.

The present owners left Wounded Knee and listed the property for sale for nearly $4 million, a price far out of reach for the tribe.

In 2013, actor Johnny Depp announced he would buy the property and donate it to the Oglala tribe. Three years later, then-newspaper owner Tim Giago proposed buying it and constructing a museum there. Both projects fell through.

Alabama University Holds Largest Collection of Indigenous Remains to Date

The U.S. National Park Service (NPS) says the University of Alabama has completed an inventory of its archeological holdings, which contain the largest number of indigenous human remains and artifacts ever catalogued by the Park Service.

According to an announcement in the Federal Register, the University of Alabama Museums conducted excavations at Moundville and other sites in Alabama’s Hale and Tuscaloosa Counties between 1930 and 2003, taking away the physical remains of 10,245 Native American ancestors and more than 1,500 artifacts.

In November 2021, a delegation of Muscogee (Creek) leaders met with the university requesting the return of those remains and artifacts. Months earlier, the Muscogee and six other tribes -- the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole Nations in Oklahoma, the Coushatta Tribe in Louisiana, the Seminole Tribe in Florida, and Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town -- sent a claim to the university invoking the 1990 federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which requires federally funded institutions to return remains to tribes and families to whom they belong.

The University of Alabama Museums has acknowledged “a cultural affiliation” with the present-day Muskogean-speaking tribes and is calling on them to submit a written request to return the remains and artifacts.

“We are just reiterating that we look forward to continuing to work with the tribes on the appropriate repatriation efforts,” the University of Alabama associate vice president for communications, Monica Watts, told VOA.

Moundville was occupied for seven centuries and at its height was a 121-hectare fortified city positioned on a bluff overlooking the Black Warrior River in west-central Alabama. By the 1500s, it had been abandoned for reasons scholars still debate; the first Spanish conquerors arrived in the state in 1519.

The university is only one of more than 150 institutions which have conducted inventories of their holdings since mid-September 2021, as NAGPRA requires. To see the full list, click on this link:

California City Considers Giving Land Rights to Two Tribes

Oakland, California will consider returning two hectares of city land to the Indigenous peoples from whom it was taken.

If approved, the proposed “cultural conservation easement” would allow the East Bay Ohlone tribe and the Confederated Villages of Lisjan Nation to immediately begin using and maintaining the land known as Sequoia Point. The city, however, would retain ownership of the area.

“Today we are letting healing begin,” Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf said at a press conference on the site. “Today is the day when we acknowledge the harm that government and colonialization has done to the first people of this land. The original sin of Native genocide that happened right here on this land was just the beginning of additional exclusionary laws and acts that have happened over generations.”

She said the city could eventually sell the land to the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, which represents the two tribes.

Oakland to return land rights to Indigenous group

South Dakota Tribes Buy Land Near Wounded Knee Massacre Site

Two American Indian tribes in South Dakota have joined forces to purchase 40 acres around the Wounded Knee National Historic Landmark, the site of one of the deadliest massacres in U.S. history.

The Oglala Sioux and the Cheyenne River Sioux said the purchase of the land on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation was an act of cooperation to ensure the area was preserved as a sacred site. More than 200 Native Americans — including children and elderly people — were killed at Wounded Knee in 1890. The bloodshed marked a seminal moment in the frontier battles the U.S. Army waged against tribes.

"It's a small step towards healing and really making sure that we as a tribe are protecting our critical areas and assets," Oglala Sioux Tribe President Kevin Killer told The Associated Press.

The tribes agreed this week to petition the U.S. Department of the Interior to take the land into trust on behalf of both tribes. The Oglala Sioux tribe will pay $255,000 and the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe will pay $245,000 for the site, Indian Country Today reported. The title to the land will be held in the name of the Oglala Sioux tribe.

Marlis Afraid of Hawk, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe whose grandfather, Albert Afraid of Hawk, survived the 1890 massacre as a 13-year-old boy, said she was overjoyed to see the tribes take ownership. She said she carries on the oral tradition of telling her grandchildren how her grandfather survived by fleeing through a ravine after a rifle held by a U.S. calvary soldier failed to fire at him.

As a member of a group that represents the descendants of the massacre's survivors, she had initially raised objections to the Oglala Sioux Tribe's purchase of the land, but said the joint purchase made her feel "honored and grateful."

Members of the Oglala Sioux, Standing Rock Sioux, Rosebud Sioux and Cheyenne River Sioux tribes were all at Wounded Knee in 1890, Afraid of Hawk said.

She hoped the site could be used for "education for the people who come and see the massacre site."

"They need to know the history. It needs to come through the true, true Lakota people," she said.

The tribes' agreement ends a decades-long dispute over ownership of a site that has figured largely in Indigenous people's struggles with the U.S. government. Jeanette Czywczynski became sole owner of the property after her husband, James, died in 2019. He had purchased the property in 1968.

The Czywczynski family operated a trading post and museum there until 1973, when American Indian Movement protesters occupied the site, destroying both the post and Czywczynski's home.

The 71-day standoff that left two tribal members dead and a federal agent seriously wounded led to heightened awareness about Native American struggles and propelled a wider protest movement.

The family moved away from the area and put the land up for sale, asking $3.9 million for the 40-acre parcel nearest the massacre site even though the land, including an additional adjacent 40-acre plot, had been assessed at $14,000.

In 2013, film star Johnny Depp announced a plan to buy the property and donate it to the Oglala Sioux tribe. Depp, who played the role of Tonto in a remake of the film, "The Lone Ranger," was criticized for trying to capitalize on the film by making unsubstantiated claims of having Native American ancestry. Depp did not follow through on the purchase.

Killer, the Oglala Sioux Tribe's president, said the tribe's resolution for the land purchase calls for it to be preserved as a sacred site.

He said, "There's still a lot of unresolved artifacts and items that should be left undisturbed."

Manny Iron Hawk, another member of the Wounded Knee Survivor's Association, said he saw the land acquisition as another step in the century-old Indian revival movement known as the Ghost Dance. The U.S. military was trying to suppress the Ghost Dance in 1890 after it had swept across Indigenous communities with a prophecy that colonial expansion would end and Native American communities would unite for prosperity.

"The Ghost Dance was a beautiful dream for our people. It wasn't a dream of death, it was a dream of life," Iron Hawk said. "Today we are the new Ghost Dancers and we carry on a duty that came to us to do what we can for our relatives there at Wounded Knee."

Malerba Sworn in as 1st Native American in US Treasurer Post

Mohegan Chief Marilynn "Lynn" Malerba was sworn in Monday as the Treasurer of the United States, the first Native American to hold that office.

Her signature will now appear alongside Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on U.S. currency.

Yellen hailed the appointment at the Treasury Department ceremony as a sign of the Biden administration's "respect for, and commitment toward, our nation-to-nation relationship, trust and treaty responsibilities, and tribal sovereignty and self-determination."

"For all our progress — there is more work to do to strengthen our nation-to-nation relationship with tribal governments," Yellen said in prepared remarks.

They were joined by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to lead that department, and members of Treasury's Tribal Advisory Committee.

Malerba, who will remain lifetime chief of the Mohegan Indian Tribe, which is made up of roughly 2,400 people, previously worked as a registered nurse and has served in various tribal government roles.

Biden appointed her U.S. treasurer in June and as overseer of a new Office of Tribal and Native Affairs at the Treasury Department.

She is tasked with finding new ways to help tribes develop their economies to overcome challenges that are unique to tribal lands, among other responsibilities.

As part of the ceremony, Malerba signed a book presented by Bureau of Engraving and Printing Director Len Olijar, who will engrave her signature. Her official signature will appear as "Lynn Roberge Malerba" in honor of her maiden name.

A Treasury official said her name will appear on currency in the coming months.

"We all know that, historically, many promises have not been kept to the indigenous peoples of this nation. But we can and will do better," said Malerba, who wore a red and black tribal ensemble and matching headdress. "My appointment is a promise kept."

"When barriers to economic development are eliminated, tribal communities will thrive and prosper," she said. "We know, when there is robust tribal economic development, our local and state communities prosper as well."

She added that the moment made her think deeply of her parents. "My name will be on currency, when it was so difficult for them to get money in their lifetime," she said during the ceremony.

For Malerba, she said she hopes her presence at Treasury will help other Americans feel pride in honoring their culture.

"Katantuoot, wuyunomsh United States qa wuyunomsh kiyawin," she said. "Great spirit bless these United States and bless us all."

Crow Tribe Journalism Teacher Seeks Stories No One Tells

Luella Brien initially wanted to be a schoolteacher but never thought she’d be one after taking a different career path. Shortly after graduating high school, she pivoted from education to pursue journalism.

Now those paths have converged in her new position as the journalism teacher at Lodge Grass High School.

No one was more surprised by the career change than Brien, who was offered the job weeks before the new school year by her predecessor Ben Cloud during a summer audio reporting workshop with students.

“Towards the end of the camp he just sort of says to me, ‘By the way, I’m retiring. Do you want to teach next year?’” she said with a laugh.

Already juggling jobs as the tour manager for the Crow Tribe and editor for the online news company Four Point Media, she was initially hesitant to take the position. But she ultimately accepted it, realizing the opportunity to expand local journalism with her students.

In addition to her career as a Montana journalist, Brien also worked as an instructor at Little Big Horn College and a media consultant for the Crow Tribe and Apsáalooke Legislature.

Despite not seeking the job, she feels uniquely qualified for it.

“It’s always been news,” she told The Billings Gazette. “I was either covering news or I was teaching others about news, so it’s always been a part of my work.”

Journalistic pursuits

Brien’s interest in reporting started while growing up in Hardin. Skimming her father’s daily newspapers once he was finished with them. What started out as skipping to the comics led to finding her name in the scholastic achiever’s list and eventually to learning about current events through local articles.

As she grew older, she noticed the lack of news focusing on the Crow Indian Reservation. She said it was her curiosity about a family member who went missing that spurred her own journalistic pursuits. She pestered family members who were reluctant to discuss it and neighbors to find out what everyone knew about the disappearance.

She learned that people went missing from her community, often without much of a follow-up investigation, more often than she thought.

“As I got to talking with more and more people, I found out that a lot of families have similar stories to mine,” she said. “So I wanted to tell the stories of our community that no one tells.”

Brien graduated from Hardin High School in 1999 and earned a liberal arts degree from Little Bighorn College in 2004. The lack of interesting job opportunities and her enjoyment of journalism courses led her to earn a bachelor’s degree in journalism at the University of Montana in 2006.

This would land her reporting jobs with the Ravalli Republic, Billings Gazette and, most recently, the Big Horn County News. It was back in her home county where she finally realized her goal of highlighting Crow Reservation news in a way it hadn’t previously. Her position as the paper’s editor and general manager led the paper’s coverage of tribal affairs to increase significantly.

She believes the rapport she developed with the community over the years also gave her the chance to tell their stories, which other reporters may not have gotten to.

“I don’t speak Crow, but the people there know me,” she said. “It didn’t matter if I had moved away for a few years or not. They remember me and they trust me.”

Dead Indians or feathered Indians

Brien said tribal communities like those in Big Horn County had grown disillusioned by most news outlets’ coverage of their lives and communities due to its limitations and depictions. Specifically, she said, most of these stories reported on either crime or tribal events highlighting their history and culture.

“We’re either dead Indians or feathered Indians,” she said. “Too often these news outlets will fly in or drive into town, get what they want or need and go on to tell the story they want to tell.”

This trend of misrepresentation and sensationalizing extends to nationally published papers like The New York Times, which reported on the disappearances of Crow women Kaysera Stops Pretty Places and Selena Not Afraid. Brien said reporters were quick to speak with Stops Pretty Places’ family shortly after she went missing but didn’t report it until after Not Afraid went missing the following January.

“So, Kaysera’s story is just sitting there for months, nothing’s getting done, and then Selena goes missing and they’re back immediately to talk with her family,” she said. “Then the story comes out and Kaysera is only mentioned towards the end. How much longer was that story going to sit there before they decided to run it?”

Coverage like this and previous stories led Native communities to avoid talking to news reporters and rely more on local sources like Big Horn County News. Her shift toward more reservation coverage wasn’t welcomed by everyone. Almost daily conflicts between the broader community and the paper prompted Brien to leave the paper in 2021 and launch Four Points Media.

The online news outlet focuses solely on the Crow Reservation in Big Horn County and to date has been funded through various grants. It was quickly met with positive results with over 3,000 readers visiting its website in the first month.

Funding inconsistency and Brien being its only contributor led to initial hiccups, however. The company’s website, Four Points Press, is due to relaunch this month while a recently hired reporter and additional board member will help sustain operations going forward.

The need is there

Four Points Media is far from the only local news outlet struggling to find its financial footing. Sam Sandoval is the editor of Char-Koosta News, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes’ official newspaper, and says the paper could cover more news throughout their community with additional staff and resources.

The paper has reached out to the University of Montana’s journalism program about potential tribal reporters, but travel distances, lack of familiarity with the community and its small population has made it a less-attractive option for reporters. Sandoval has also reached out to nearby high school newspapers in Pablo, Ronan and Polson for potential contributors but said declining student interest has resulted in inconsistency in recent years.