Native Americans

US Changes Names of Places With Racist Term for Native Women

The U.S. government has joined a ski resort and others that have quit using a racist term for a Native American woman by renaming hundreds of peaks, lakes, streams and other geographical features on federal lands in the West and elsewhere.

New names for nearly 650 places bearing the offensive word "squaw” include the mundane (Echo Peak, Texas), peculiar (No Name Island, Maine) and Indigenous terms (Nammi'I Naokwaide, Idaho) whose meaning at a glance will elude those unfamiliar with Native languages.

Nammi'I Naokwaide, located in traditional lands of the Shoshone and Bannock tribes in southern Idaho, means "Young Sister Creek." The tribes proposed the new name.

"I feel a deep obligation to use my platform to ensure that our public lands and waters are accessible and welcoming. That starts with removing racist and derogatory names that have graced federal locations for far too long,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said in a statement.

The changes announced Thursday capped an almost yearlong process that began after Haaland, the first Native American to lead a Cabinet agency, took office in 2021. Haaland is from Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico.

The Native American Rights Fund, a nonprofit legal organization, welcomed the changes.

"Federal lands should be welcoming spaces for all citizens," deputy director Matthew Campbell said in a statement. "It is well past time for derogatory names to be removed and tribes to be included in the conversation.”

Haaland in November declared the term derogatory and ordered members of the Board on Geographic Names, the Interior Department panel that oversees uniform naming of places in the U.S., and others to come up with alternatives.

Haaland meanwhile created a panel that will take suggestions from the public on changing other places named with derogatory terms.

Other places renamed include Colorado's Mestaa'ėhehe (pronounced "mess-taw-HAY") Pass near Mestaa'ėhehe Mountain about 30 miles (48 kilometers) west of Denver. The new name honors an influential translator, Owl Woman, who mediated between Native Americans and white traders and soldiers in what is now southern Colorado.

The Board on Geographic Names approved changing the mountain's name in December.

While the offensive term in question, identified as "sq___” by the Interior Department on Thursday, has met wide scorn in the U.S. only somewhat recently, changing place names in response to broadening opposition to racism has long precedent.

The department ordered the renaming of places carrying a derogatory term for Black people in 1962 and those with a derogatory term for Japanese people in 1974.

The private sector in some cases has taken the lead in changing the offensive term for Native women. Last year, a California ski resort changed its name to Palisades Tahoe.

A Maine ski area also committed in 2021 to changing its name, two decades after that state removed the slur from names of communities and landmarks, though it has yet to do so.

The term originated in the Algonquin language and may have once simply meant "woman.” But over time, the word morphed into a misogynist and racist term to disparage Indigenous women, experts say.

California, meanwhile, has taken its own steps to remove the word from place names. The state Legislature in August passed a bill that would remove the word from more than 100 places beginning in 2025.

Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom has until the end of September to decide whether to sign the bill into law.

Native American News Roundup, Aug. 28 - Sept. 3, 2022

First Alaska Native Elected to U.S. Congress

Mary Peltola, an Alaska Yup’ik Native, has won a special election to become the first Alaska Native and the first Alaskan woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

“I am honored, humbled, and absolutely speechless,” Peltola posted on Facebook shortly after the results were announced. “Thank you, Alaska…Together, we overcame all odds and showed that Alaskans can come together––regardless of party affiliation––to put Alaska first.”

The election was held August 16, but it took some time to tally the votes. Under the state’s new ranked-choice election system, voters list candidates in order of preference. If a candidate wins a majority of first-preference votes, that candidate is the winner. If no candidate wins a majority of first-preference votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and a new count is made. That process is repeated until one candidate wins a majority of votes.

Peltola is a member of the Democratic Party and will serve the remaining four months of the late Republican Representative Don Young’s term. She defeated former Alaska governor and 2008 vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, whom former President Donald Trump endorsed in April as a “true America First fighter.”

Alaska Native elected to Congress

DOI to Consult with Tribes on Draft Guidelines for Plugging Abandoned Wells

The Interior Department has released draft guidelines to help tribes apply for $50 million in grants to help clean up abandoned oil and gas wells on tribal lands.

The Environmental Defense Fund says there are 81,000 inactive wells which fuel extraction companies failed to plug before leaving. Thousands are located on reservations. Orphaned wells leak gases and chemicals into the air and groundwater, posing significant health risks to humans, wildlife and the environment.

While no longer producing oil and gas, they have yet to be shut down -- a process that involves cementing the well bore, clearing off equipment, cleaning up any pollution in the soil or water, and grading and seeding the land to resemble what it once was.

Last year’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocates $4.7 billion to help plug these orphaned wells across the U.S., including $150 million for Tribal communities.

“We are making historic investments to reclaim orphaned oil and gas wells on Tribal lands and restore habitats and ecosystems in the degraded areas,” Secretary Deb Haaland said. “We have engaged in nation-to-nation consultations since the inception of this program and are eager to hear from Tribal leaders as we work to finalize this guidance.”

Biden-Harris Administration releases draft guidance on new Tribal orphaned well program

University Acknowledges It Holds Boxed Up Native American Remains, Artifacts

The University of North Dakota (UND) says it found dozens of remains of Native Americans and historic artifacts on its Grand Forks campus and is working to repatriate them to their families.

In a Zoom conference Wednesday, UND President Andrew Armacost said a group of educators discovered in March the partial skeletal remains of about 70 individuals, along with artifacts -- more than 250 boxes in all -- likely taken from burial mounds “over the course of decades.”

One of those educators was Laine Lyons, an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians and director of development at the College of Arts & Sciences. She described the shock of the discovery.

“In that moment, my heart sank into my stomach,” she said. “It was at that moment that I knew we were another institution that didn't do the right thing.”

Armacost did not say why the University had not returned the remains and artifacts earlier, as mandated by the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) but said the school is “fully committed to righting this wrong.”

The school has organized a NAGPRA Compliance Committee to work with more than a dozen tribal representatives to come up with a process for sending home the ancestors and artifacts.

Nathan Davis, director of the North Dakota Indian Affairs Commission and also a member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa, said he is feeling hurt and angry.

“In our way, in our culture…when one of our loved ones passes on, they are mourned over, they are prayed over, and there is a ceremony for them to begin their journey,” he said. “And once we put them in the ground, and they become one with our mother, that is where they are to stay.”

Indigenous ancestors found on North Dakota college campus

NAJA to Change Its Name and Blur ‘Medicine Line’

The Native American Journalists Association is rebranding and expanding.

At its annual conference in Arizona, NAJA president Francine Compton said the group has “talked about changing the name for a couple of years now, and we were finally able to show our membership in person how we have a new local concept and that we're going in the direction of changing our name to Indigenous Journalists Association.”

NAJA was founded in 1983 to help bring Indigenous voices to mainstream newsrooms. NAJA membership is to citizens of Native American tribes, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, citizens of First Nations, and their non-Indigenous allies in media.

Compton is a citizen of the Sandy Bay Ojibway First Nation in Canada and a reporter for CBC Indigenous in Winnipeg. She told VOA, “Some indigenous journalists in Canada they have said, ‘I didn't know NAJA included me because of its name. So, [the name change] will help us expand north to Canada and allow us to represent any indigenous journalist around the world who needs our support or wants to support us.”

Compton said the board first proposed the name change during a virtual conference in 2020, adding that some NAJA members opposed the move.

“We still want to consider and hear their concerns and have done our duty to give them time for consultation and feedback,” she said.

Former NAJA president and current Indian Country Today editor-at-large Mark Trahant said he supports the idea.

“Especially since [the Indigenous Canadian sovereignty movement] Idle No More and Standing Rock, there have been far more social media connections on both sides of the Medicine Line -- and a growing number from other Indigenous communities,” Trahant said in an email.

He used a term Indigenous North Americans used for more than a century to reference the U.S.-Canada border, which split homelands, tribes, economies and families, preventing free movement tribes had enjoyed for millennia.

“Some of the discussions NAJA/IJA has been having are also taking place here,” Trahant said, adding that eight percent of his publication’s readership is in Canada. “We rebranded as ICT for many of the same reasons.”

Chinook Tribe to Lawmakers: If BIA Won’t Acknowledge Us, Will You?

The Chinook Nation in Washington State is launching a new push for federal recognition with a rally and #ChinookJustice Twitterstorm, hopeful that Congress can restore their official relationship with the federal government.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) officially recognized the Chinook Nation in 2001, giving the tribe access to health, housing, medical and other federal benefits and protections.

But the BIA rescinded that status 18 months later, ruling that between 1873 and 1951 the tribe did not exist as a distinct and “substantially continuous” entity, one of seven criteria tribes must meet to be officially recognized.

Tribe members rallied on the steps of a federal building in Seattle on Monday, calling on Washington Senators Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell to help pass legislation recognizing the Chinook.

But the Chinook face strong opposition from the Quinault Nation, also in Washington State, a factor that could discourage lawmakers from acting.

In a statement to Northwest Radio, Senator Murray acknowledged the importance of tribal recognition, saying only that she would “do her best to serve as a voice for Washington’s tribal people.”

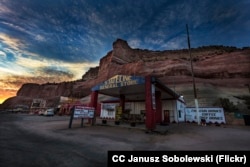

Chinook Nation rallies in support of federal recognition

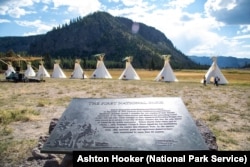

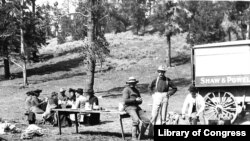

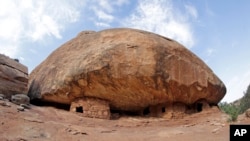

Yellowstone at 150: Acknowledging Indigenous History

This year marks 150 years since President Ulysses S. Grant set aside nearly 9,000 square kilometers in parts of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho as “a park and pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

What became Yellowstone National Park was not the unclaimed wilderness that explorers described. For at least 10,000 years it had been inhabited, first by the so-called Clovis people, the ancestors of today’s Indigenous North Americans, who left behind spear points, pictographs and other evidence of their occupation of the land.

In more recent centuries, the park was home—permanently or seasonally—to 49 tribes, according to William “Bill” Snell Jr., President of the Pretty Shield Foundation, Executive Director of Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council and an enrolled citizen of the Crow Nation.

In a 2007 article in the Public Land and Resources Law Review, “Ethnic Cleansing and America's Creation of National Parks, Montana lawyer Isaac Kantor noted that for the most part, tribes continued to maintain their presence in the park, exercising their treaty rights to hunt there in spite of local and state bans.

“Both forcible and legal efforts were pursued to end Indian use of Yellowstone,” he wrote. “In July of 1895, when pressure from park officials and Indian agents proved inadequate, a Jackson Hole area lawman, William Manning, decided on a violent approach to 'get the matter to the courts.’”

In the 1990s, tribes requested formal association with the park. Today, the National Park Services says it meets and consults with 27 tribes, exploring possibilities for giving them a greater voice in resource management and decision-making.

VOA correspondent Natasha Mozgovaya traveled to Yellowstone for ceremonies marking its 150th anniversary and spoke with members of several tribes with historic ties to the park.

Yellowstone Park Anniversary Highlights Stories of First Tribes

Yellowstone Park Anniversary Highlights Stories of First Tribes

In the Western U.S. states of Montana and Wyoming, Yellowstone National Park is celebrating its 150th anniversary by promoting the stories of native tribes forced from the park at its founding. VOA’s Natasha Mozgovaya has the story. Video: Natasha Mozgovaya, Scott Stearns

Native American News Roundup, August 21-27, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

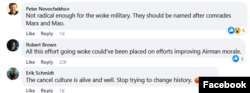

Air Force Base in Washington State to Rename Housing Units

Fairchild Air Force Base in Washington State has announced it will change the names of all parts of the base named after George Wright, a 19th-century Army general with a record of unusual cruelty against tribes in the northeast of the state.

"We are renaming Ft Wright Village and Ft Wright Oval in base housing to Lilac Village and Willow Loop," Fairchild Air Force Base posted on Facebook Monday. "This change is the result of long consideration by Fairchild leadership, in accordance with an Air Force directive to evaluate historically divisive names on installations."

In the autumn of 1858, then-Colonel Wright launched a two-month campaign against the Spokane, Palouse and Coeur d'Alene tribes to avenge an Army defeat several months earlier.

Donald Cutler, in his book "Hang Them All": George Wright and the Plateau Indian War, 1858, described Wright's strategy for dealing with tribes, writing, "Col. Wright, by admitting his intent was to strike fear into the tribes, showed that he understood the power of cruelty."

Wright captured and slaughtered 900 Indian horses, burned tribes' crops and food supplies, and staged public hangings that Cutler describes as "theatrically gruesome."

Fairchild's announcement generated some criticism on Facebook, coming amid vigorous debate in the U.S. about history, democracy and patriotism in America, which has seen the removal of dozens of Confederate and Christopher Columbus statues and reviews of the way history is being taught in some school districts.

In 2021, the city of Spokane, Washington, renamed a street that formerly carried Wright's name. The new name is Whistalks Way, after a Spokane woman warrior who played a key role in resisting Wright.

Air Force erasing decorated Union Army veteran from base over 'brutal acts' towards Native Americans

Labor Department to Boost Native American Employment, Training Programs

The U.S. Department of Labor has announced the award of $70.8 million in grant funding to 166 Indian and Native American tribes and organizations to help provide employment and training services to low-income and unemployed Native Americans, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians to help them compete in today's workforce.

Of the funds awarded, $56,351,790 will serve low-income and unemployed American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians. The remaining $13,932,627 will serve low-income American Indian, Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian youth ages 14-24 living on or near Indian reservations or in Hawaii.

The unemployment rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives has declined since April 2020, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when it hit 28.6 percent, nearly double the seasonally adjusted rate of 14.7 percent for the total population.

The lack of employment and/or educational opportunities in or near Indian reservations is one of the biggest challenges to tribal well-being today. In February, for the first time ever, the Bureau of Labor Statistics published data showing that the Native American unemployment rate in December 2021 was 7.9 percent, a rate much higher than the rate of 3.9 percent for the general U.S. population.

Cherokee Lawmaker is GOP Nominee for US Senate Seat

Conservative U.S. Representative Markwayne Mullin of Oklahoma, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, this week won the Republican nomination for the Senate seat currently held by James Inhofe, who is set to retire at the end of the year.

In November midterm elections, Mullin will face off against the Democratic candidate, former U.S. Representative Kendra Horn.

Mullin, a businessman and former mixed martial arts fighter, is widely viewed as the favorite in Oklahoma, where Republicans control the offices of governor, secretary of state, attorney general and both chambers of the state Legislature.

Markwayne Mullin wins Republican bid for U.S. Senator Inhofe's seat

Wailaki Astronaut to Head for the Stars

As a former Marine Corps test pilot, Nicole Aunapu Mann, a Wailaki citizen of the Round Valley Indian Tribes in Northern California, has flown on many missions, but none can compare to the flight she's about to undertake next month: commanding a crew of five on a SpaceX flight to the International Space Station.

Once she reaches the ISS, she'll spend six months conducting science experiments.

"One of the ones that I'm looking most forward to is called the biofabrication facility. And it is literally 3D printing human cells," she told Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, editor of Indian Country Today.

Scientists have long envisioned using 3D biological printers to print human organs, but they've found it nearly impossible to print finer tissue, such as capillaries, in Earth's gravitational environment. That's because gravity flattens and deforms 3D-printed tissue. But in space, the lack of gravity allows 3D printed tissues to hold up.

Flying with Mann will be NASA astronaut Josh Cassada, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency astronaut Koichi Wakata and Russian cosmonaut Anna Kikina.

In 2002, John Herrington of the Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma became the first Native American in space.

September's space trip may not be Mann's last: In 2020, she was also selected to be one of a group of eligible astronauts to travel to the moon as part of NASA's Artemis program.

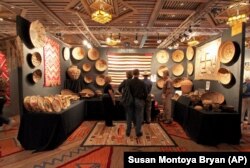

Pueblo Potter Takes Top Prize in Santa Fe Indian Market

Over the weekend, the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts announced winners of the 100th annual Santa Fe Indian Market in New Mexico, the largest Native North American art market in the world.

San Ildefonso Pueblo potter Russell Sanchez won best in show — and a $30,000 award — for a lidded clay jar described as a contemporary interpretation of traditional Pueblo craftsmanship.

A bear stands atop the lid, an animal the Pueblo people associate with strength and protection. Winding around the center of the jar is the deity Avanyu, a plumed water serpent to whom Sanchez's ancestors appealed to in times of drought.

Sanchez still fires his clay pieces outdoors in the traditional Pueblo manner, using cedar and dried cow or horse dung as fuel. He then carves, paints and polishes his pieces, which are inlaid with minerals and gemstones.

Navajo silversmith Ernest Benally won best in the jewelry category for a belt made of a dozen turtles, each embedded with turquoise, lapis lazuli and other gemstones.

To see the full list of winners in 10 categories, click on the link below; to see photos of the winning artworks, visit SWAIA's Facebook page.

Santa Fe Indian Market Announces Centennial Best of Show Winners

Digital Solution Aims to Thwart Counterfeiters of Native Art

In a related story, counterfeit Native American art is a big problem in the U.S. and abroad. Jewelry, paintings and crafts falsely marketed as Native-made make big money for fraudsters but drive down the value of genuine Native art and denies Native artists a livelihood.

In one highly publicized case, federal investigators in 2015 raided 11 jewelry and Indian arts stores in New Mexico and California, seizing 350,000 pieces of Filipino-made jewelry with a retail value of $35,000,000.

This week, the art security registry Imprint announced it would partner with the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts to supply 800 Native American artists with permanently certified Imprint digital titles to their artwork.

Imprint gives artists and galleries permanent digital titles that allow them to officially register and create a digital certificate of authenticity that will be stored on a secure blockchain database — a digital "ledger" of all art transactions.

This means that buyers of Native artwork can be sure that they are getting works by legitimate Native artists, not frauds. Squeezing out the fakes means that genuine Native artworks retain or increase their value.

"When Imprint approached us to launch their blockchain-based art security registry with SWAIA artists, we immediately recognized the opportunity as one that will help combat theft and counterfeit within the Native American art world," said SWAIA Executive Director Kimberly Peone, an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in Nespelem, Washington, and an Eastern Band of Cherokee descendant. "We are thrilled to be able to provide cutting-edge solutions to SWAIA artists."

The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 was intended to protect Native American artists by imposing fines and prison time for counterfeiting. Any individual falsely selling or presenting work as Native American can face civil or criminal penalties up to a $250,000 fine and/or a five-year prison term; any business selling fakes can face civil penalties or can be prosecuted and fined up to $1,000,000.

As Inflation Soars, Access to Indigenous Foods Declines

Blueberry bison tamales, harvest salad with mixed greens, creamy carrot and wild rice soup, roasted turkey with squash. This contemporary Native American meal, crafted from the traditional foods of tribes across the United States and prepared with "Ketapanen" – a Menominee expression of love – cost caterer Jessica Pamonicutt $976 to feed a group of 50 people last November.

Today it costs her nearly double.

Pamonicutt is the executive chef of Chicago-based Native American catering business Ketapanen Kitchen. She is a citizen of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin but was raised in the Windy City, home to one of the largest urban Native populations in the country, according to the American Indian Center of Chicago.

Her business aims to offer health-conscious meals featuring Indigenous ingredients to the Chicago Native community and educate people about Indigenous contributions to everyday American fare.

One day, she aims to purchase all ingredients from Native suppliers and provide her community with affordable access to healthy Indigenous foods, "but this whole inflation thing has slowed that down," she said.

U.S. inflation surged to a new four-decade high in June, squeezing household budgets with painfully high prices for gas, food and rent.

Traditional Indigenous foods — like wild rice, bison, fresh vegetables and fruit in the Midwest — are often unavailable or too expensive for Native families in urban areas like Chicago, and the recent inflation spike has propelled these foods even further out of reach.

Risk of disease compounds the problem: healthy eating is key to battling diabetes, which afflicts Native Americans at the highest rate of any ethnic group in the United States.

"There are many benefits to eating traditional Native foods," said Jessica Thurin, a dietician at Native American Community Clinic in Minneapolis. "The body knows exactly how to process and use that food. These foods are natural to the Earth."

But many people the clinic serves are low-income and do not have the luxury of choosing where their food comes from. Food deserts – areas with limited access to a variety of healthy and affordable foods – are more likely to exist in places with higher rates of poverty and concentrations of minority populations.

"In these situations, there are limited healthy food options, not to mention limited traditional food options," Thurin said.

Aside from health benefits, traditional foods hold important cultural and emotional value.

"It's just comfort," said Danielle Lucas, a 39-year-old descendant of the Sicangu Lakota people from the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota.

Lucas' mother, Evelyn Red Lodge, said she hasn't prepared traditional dishes of the Great Plains, like wojapi berry sauce or stew, since May because the prices of key ingredients – berries and meat – have soared.

Pamonicutt, too, is feeling the pinch. Between last winter and this spring, the price of bison jumped from $13.99 to $23.99 per pound.

Shipping costs are so high that the chef said it's often cheaper to drive hundreds of miles to buy ingredients, even with spiking gas prices. She's even had to create her own suppliers: the 45-year-old's parents are now growing crops for her business on their Wisconsin property near the Illinois border.

Gina Roxas, program coordinator at Trickster Cultural Center in Schaumburg, Illinois, a Chicago suburb, has also agreed to grow Native foods to help the chef minimize costs.

When a bag of wild rice costs $20, "you end up going to a fast food place instead to feed your family," Roxas said.

More than 70% of Native Americans reside in urban areas – the result of decades of federal policies pushing families to leave reservations and assimilate into American society.

Dorene Wiese, executive director of the Chicago-based American Indian Association of Illinois, said members of her community have to prioritize making rent payments over splurging on healthy, traditional foods.

Even though specialty chefs like Pamonicutt aim to feed their own communities, the cost of her premium catering service is out of the price range for many urban Natives. Her meals end up feeding majority non-Native audiences at museums or cultural events that can foot the bill, said Wiese, a citizen of the Minnesota White Earth Band of Ojibwe Indians.

"There really is a shortage of Native foods in the area," she said, But the problem isn't unique to Chicago.

Dana Thompson, co-owner of The Sioux Chef company and executive director of a Minneapolis Indigenous food nonprofit, is another Native businesswoman striving to expand her urban community's access to traditional local foods like lake fish, wild rice and wild greens amid the food price surge.

Thompson, of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate and Mdewakanton Dakota people, said inflation is "really impacting the food systems we have here," which include dozens of Indigenous, local and organic food producers.

At Owamni, an award-winning Indigenous restaurant under The Sioux Chef umbrella, ingredients like Labrador Tea – which grows wild in northern Minnesota – have been especially difficult to get this year, Thompson said.

When an ingredient is not consistently available or affordable, she changes the menu.

"Being fluid and resilient is what we're used to," Thompson said. "That's like the history of indigeneity in North America."

Inflation is similarly impeding the American Indian Center of Chicago's efforts to improve food security. Executive Director Melodi Serna, of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians and the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, said the current prices of food boxes they distribute – with traditional Midwestern foods like fish, bison, venison, dairy products and produce – are "astronomical."

"Where I could have been able to provide maybe 100 boxes, now we're only able to provide 50," Serna said.

For 57-year-old Emmie King, a Chicago resident and citizen of the Navajo Nation, getting the fresh ingredients she grew up with in New Mexico is much more difficult in the city, especially with inflation biting into her budget.

She finds ways to "stretch" the food she buys so it lasts longer, purchasing meat in bulk and freezing small portions to add to stews later on. "I get what I need, rather than what I want," she said.

But King was able to enjoy a taste of home at an Aug. 3 luncheon at the American Indian Center of Chicago, where twenty elders gathered to enjoy turkey tamales with cranberry-infused masa, Spanish rice with quinoa, elote pasta salad with chickpea noodles and glasses of cold lemonade.

The mastermind behind the meal was Pamonicutt herself, sharing her spin on Southwestern and Northern Indigeneous food traditions. Through volunteering at senior lunches and developing a food education program, the chef is continuing to increase access to healthy Indigenous foods in her community.

"I want kids to learn where these foods come from," the chef said. "That whole act of caring for your food … thanking it, understanding that it was grown to help us survive."

Native American News Roundup, August 14-20, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

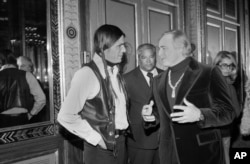

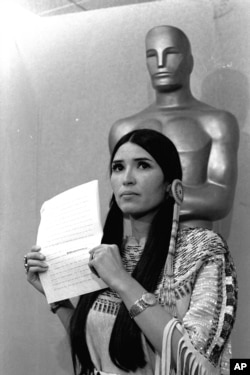

Oscars Apologize to Sacheen Littlefeather 50 Years After Marlon Brando Protest Speech

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is apologizing to Sacheen Littlefeather, the actress who spoke for Marlon Brando at the 1973 Academy Awards ceremony rejecting his Best Actor award over the mistreatment of Native Americans.

In a 45-second speech, Littlefeather explained Brando’s rationale was to protest “the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry and on television in movie reruns, and also with recent happenings at Wounded Knee,” referencing the then-month-old occupation of a small settlement on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

She was ushered offstage to gasps and jeers; backstage, she read out loud a more than 700-word statement from Brando protesting America’s treatment of Native Americans.

“We lied to them. We cheated them out of their lands. We starved them into signing fraudulent agreements…” Brando wrote. “What kind of moral schizophrenia is it that allows us to shout at the top of our national voice … that we live up to our commitment [to Indians] when every page of history and when all the thirsty, starving, humiliating days and nights of the last 100 years in the lives of the American Indian contradict that voice?”

Littlefeather’s speech broke an FBI-imposed media blackout of the Wounded Knee standoff.

“After that incident I was boycotted,” Littlefeather said in a 2019 short film, Sacheen: Breaking the Silence. “The FBI went around Hollywood and told … production companies that if they had me on their show that they would shut down their production.”

On June 18, then-Academy head David Rubin wrote an open “statement of reconciliation” to Littlefeather, which will be presented to her in person during an event at the Academy Museum in September.

“The abuse you endured because of this statement was unwarranted and unjustified,” the letter states. “The emotional burden you have lived through and the cost to your own career in our industry are irreparable. For too long the courage you showed has been unacknowledged. For this, we offer both our deepest apologies and our sincere admiration.”

Littlefeather, 75, reacted with wry humor.

“Regarding the Academy’s apology to me, we Indians are very patient people—it’s only been 50 years!” she said.

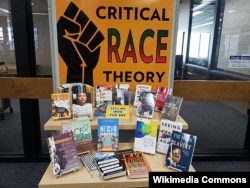

Educators Challenge Oklahoma Critical Race Theory Law

Two school systems in Oklahoma are appealing a decision by the state’s education board to downgrade their accreditation for alleged violations of a year-old state law banning discussions of race or gender in the classroom.

In Tulsa, a high school teacher complained that during professional development training in August 2021, she heard “statements that specifically shame white people for past offenses in history, and state that all are implicitly racially biased by nature.”

In January 2022, a parent complained that children in a Mustang municipality public school were made to feel uncomfortable during an anti-bullying exercise.

On July 28, the Oklahoma Education Department downgraded both schools to “accreditation with warning” status, which, according to the department’s website, means that they “failed to meet one or more of the standards and the deficiency seriously detracts from the quality of the school’s educational program.”

“This isn’t about hanging their head in shame, this is about knowing what happened," Cherokee Nation Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr., told Tulsa’s KTUL Monday. “I think if any point in history needs to be examined critically, it is how the federal government, how the United States has dealt with Indian tribes. Young people need to know this.”

Inflation Reduction Act Invests Millions in Native American Climate and Energy Projects

President Joe Biden Tuesday signed the Inflation Reduction Act, a law which aims to control inflation by reducing the deficit and lowering prescription drug prices and to combat climate change by investing in domestic energy production and promoting clean energy solutions.

The IRA will invest more than $720 million to support Native-driven climate solutions and advance Tribal energy development priorities, including:

- $150 million to help tribes install electricity in homes.

- $75 million to assist tribes in energy development.

- $225 million for developing Tribal high-efficiency electric home rebate programs.

- $235 million for Tribal climate resilience, including fish hatchery operations and maintenance.

- $25 million for climate resilience funding to the Interior Department’s Office of Native Hawaiian Relations.

- $12.5 million for Tribal emergency drought relief

The law also establishes an energy loan guarantee program to give eligible tribes and Native communities access to billions of dollars through competitive grants, loans, loan guarantees and contracts.

Ireland Honors Haudenosaunee Passports

Members of the Haudenosaunee Nationals (formerly, Iroquois Nationals) men’s under-21 lacrosse team were in Ireland this week to compete in World Lacrosse Men's U21 World Championship games and were thrilled when Dublin customs authorities acknowledged and stamped their Haudenosaunee passports.

It was a diplomatic courtesy that not all governments have extended them. As the Buffalo News reported last week, they were unable to compete in world championships in Great Britain because that nation refused to accept their passports.

"They treated us the way anyone would hope to be treated," said Nationals board member Rex Lyons.

It’s only fitting, considering that it was the Haudenosaunee who invented the game more than 1,000 years ago, and they have been playing ever since.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy consists of six Nations, the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora Nations of New York and Canada. It began issuing passports to its citizens in 1923 as an expression of their sovereignty, but other Nations haven’t always honored them. In 2010, the team was unable to participate in the championships in Great Britain, which wouldn’t accept their passports.

US Reaching out to Native Americans on Climate Change

The Federal Emergency Management Agency has developed a new strategy to better engage with hundreds of Native American tribes as they face climate change-related disasters, the agency announced Thursday.

FEMA will include the 574 federally recognized tribal nations in discussions about possible future dangers from climate change. It has earmarked $50 million in grants for tribes pursuing ways to ease burdens related to extreme weather. Tribal governments will be offered more training on how to navigate applying for FEMA funds. The new plan calls for tribal liaisons to give a yearly report to FEMA leaders on how prepared tribes are.

“We are seeing communities across the country that are facing increased threats as a result of climate change,” FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell said in a conference call with media. “What we want to do in this strategy is make sure that we can reach out to tribal nations and help them understand what the potential future threats are going to be.”

In recent years, tribal and Indigenous communities have faced upheaval dealing with changing sea levels as well as an increase in floods and wildfires. Tribal citizens have lost homes or live in homes that need to be relocated because of coastal erosion. Some cannot preserve cultural traditions like hunting and fishing because of climate-related drought.

Lynda Zambrano, executive director of the Snohomish, Washington-based National Tribal Emergency Management Council, said tribes historically had to make do with nobody to guide them. For example, over 200 Native villages in Alaska have had to share one FEMA tribal liaison. Or different tribes were told different things. So, nonprofits like the council tried to fill in gaps with their own training, she said.

“The way that I equate it to people is that they built the highway, but they never created the on ramps,” Zambrano said. “If FEMA is just now getting around to building the ramps, well, that’d be a good thing. But there needs to be very clear policy and procedure and direction—and it has to be consistent.”

Tribes have historically been disproportionately impacted by natural disasters because they are in high-risk areas and have little infrastructure, she added. They will only continue to be vulnerable.

It was only in 2013 under the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act that federally recognized tribes obtained the ability to directly request emergency and disaster declarations. Before, they had to apply for disaster funding through the states.

The new strategy emphasizes making sure tribes know of every FEMA grant program and how to apply for it. The hope is this will give them an equitable chance at getting funding. The agency hopes to find ways to get around barriers like FEMA cost share, or the portion of disaster or project funding that the federal government will cover. In some cases, tribes simply can’t afford to pay their share.

“In those areas where we can’t, what we want to do is to be able to work with the tribes to help them find other funding sources to help them stitch together the different funding streams that might be out there,” Criswell said.

However, FEMA’s new strategy to engage Native tribes seems specifically aimed at those with federal recognition. That would seem to leave out tribes that only have state recognition or no recognition. In a place like Louisiana that nuance could leave out many Native Americans most affected by climate change.

When Hurricane Ida came ashore in 2021, it devastated a large swath of southeast Louisiana that has been home to Native Americans for centuries. With climate change, hurricanes are expected to get stronger and wetter. But the tribes most affected by Ida say not having federal recognition has stymied their ability to prepare for and recover from storms.

Cherie Matherne is the cultural heritage and resiliency coordinator for the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe. Upon hearing about FEMA’s announcement, she said she wished the changes would also be applied to tribes without federal recognition like hers.

“It’s an oversight if they don’t work with state recognized tribes,” said Matherne, who is living in a trailer next to her gutted home in southeastern Louisiana. “If there are grants for tribal nations and tribal people that would be very helpful information for people to know.”

FEMA will continue to work with state and local governments to ensure state -recognized tribes are getting assistance, agency officials said.

Another change under the new strategy is more FEMA staff meeting tribes on their land, a request the agency got from multiple tribes. This will include anything from in-person technical assistance in small, rural communities to appearing at large national or regional tribal events.

Bill Auberle, co-founder of the Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals at Northern Arizona University, said this focus on regular interactions on tribal land is an immense development. More intimate discussions such as workshops, roundtables and webinars are “exceedingly important to tribes.”

“It’s one thing to send out a notice and say ‘We would like your response,’” Auberle said. “Some of those tribes are small but have very serious needs. FEMA can certainly appreciate that.”

In addition to making more funds available to tribes, FEMA could also help by providing things like technical support as tribes prepare for and adapt to climate change, Auberle said.

The push to ensure all tribes fully understand how to access FEMA assistance or other related grants will be done with webinars, tribal consultations or regular meetings with FEMA regional staff.

Agency workers will get trained as well, learning a historic and legal overview about tribal sovereignty and cultural sensitivities.

Zambrano, of the National Tribal Emergency Management Council, hope this leads to every tribal nation getting funding for an emergency management program.

“Our tribal nations are a good 30 years behind the curveball in developing their emergency management programs,” she said. “Nobody is better at being able to identify, mitigate, prepare and respond to a disaster in Indian Country than the people that live there.”

Deadline Looms for Western States to Cut Colorado River Use

Banks along parts of the Colorado River where water once streamed are now just caked mud and rock as climate change makes the Western U.S. hotter and drier.

More than two decades of drought have done little to deter the region from diverting more water than flows through it, depleting key reservoirs to levels that now jeopardize water delivery and hydropower production.

Cities and farms in seven U.S. states are bracing for cuts this week as officials stare down a deadline to propose unprecedented reductions to their use of the water, setting up what's expected to be the most consequential week for Colorado River policy in years.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in June told the states — Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — to determine how to use at least 15% less water next year, or have restrictions imposed on them. The bureau is also expected to publish hydrology projections that will trigger additional cuts already agreed to.

Tensions over the extent of the cuts and how to spread them equitably have flared, with states pointing fingers and stubbornly clinging to their water rights despite the looming crisis.

Representatives from the seven states convened in Denver last week for last-minute negotiations behind closed doors. Those discussions have yet to produce concrete proposals, but officials close to the negotiations say the most likely targets for cuts are Arizona and California farmers. Agricultural districts in those states are asking to be paid generously to bear that burden.

The proposals under discussion, however, fall short of what the Bureau of Reclamation has demanded and, with negotiations stalling, state officials say they hope for more time to negotiate details.

"Despite the obvious urgency of the situation, the last 62 days produced exactly nothing in terms of meaningful collective action to help forestall the looming crisis," John Entsminger, the general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority wrote in a letter Monday. He called the agricultural district demands "drought profiteering."

The Colorado River cascades from the Rocky Mountains into the arid deserts of the Southwest. It's the primary water supply for 40 million people. About 70% of its water goes toward irrigation, sustaining a $15 billion-a-year agricultural industry that supplies 90% of the United States' winter vegetables.

Water from the river is divided among Mexico and the seven U.S. states under a series of agreements that date back a century, to a time when more flowed.

But climate change has transformed the river's hydrology, providing less snowmelt and causing hotter temperatures and more evaporation. As the river yielded less water, the states agreed to cuts tied to the levels of reservoirs that store its water.

Last year, federal officials for the first time declared a water shortage, triggering cuts to Nevada, Arizona and Mexico's share of the river to help prevent the two largest reservoirs — Lake Powell and Lake Mead — from dropping low enough to threaten hydropower production and stop water from flowing through their dams.

The proposals for supplemental cuts due this week have inflamed disagreement between upper basin states — Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — and lower basin states — Arizona, California and Nevada — over how to spread the pain.

The lower basin states use most of the water and have thus far shouldered most of the cuts. The upper basin states have historically not used their full allocations but want to maintain water rights to plan for population growth.

Gene Shawcroft, the chairman of Utah's Colorado River Authority, believes the lower basin states should take most of the cuts because they use most of the water and their full allocations.

He said it was his job to protect Utah's allocation for growth projected for decades ahead: "The direction we've been given as water purveyors is to make sure we have water for the future."

In a letter last month, representatives from the upper basin states proposed a five-point conservation plan they said would save water, but argued most cuts needed to come from the lower basin. The plan didn't commit to any numbers.

"The focus is getting the tools in place and working with water users to get as much as we can rather than projecting a water number," Chuck Cullom, the executive director of the Upper Colorado River Commission, told The Associated Press.

That position, however, is unsatisfactory to many in lower basin states already facing cuts.

"It's going to come to a head particularly if the upper basin states continue their negotiating position, saying, 'We're not making any cuts,'" said Bruce Babbitt, who served as Interior secretary from 2003-2011.

Lower basin states have yet to go public with plans to contribute, but officials said last week that the states' tentative proposal under discussion fell slightly short of the federal government's request to cut 2 to 4 million acre-feet.

An acre-foot of water is enough to serve 2-3 households annually.

Bill Hasencamp, the Colorado River resource manager at Southern California's Metropolitan Water District, said all the districts in the state that draw from the river had agreed to contribute water or money to the plan, pending approval by their respective boards. Water districts, in particular Imperial Irrigation District, have been adamant that any voluntary cut must not curtail their high priority water rights.

Southern California cities will likely provide money that could fund fallowing farmland in places like Imperial County and water managers are considering leaving water they've stored in Lake Mead as part of their contribution.

Arizona will probably be hit hard with reductions. The state over the past few years shouldered many of the cuts. With its growing population and robust agricultural industry, it has less wiggle room than its neighbors to take on more, said Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke. Some Native American tribes in Arizona have also contributed to propping up Lake Mead in the past and could play an outsized role in any new proposal.

Irrigators around Yuma, Arizona, have proposed taking 925,000 acre-feet less of Colorado River water in 2023 and leaving it in Lake Mead if they're paid $1.4 billion or $1,500 per acre-foot. The cost is far above the going rate, but irrigators defended their proposal as fair considering the cost to grow crops and get them to market.

Wade Noble, the coordinator for a coalition that represents Yuma water rights holders, said it was the only proposal put forth publicly that includes actual cuts, rather than theoretical cuts to what users are allocated on paper.

Some of the compensation-for-conservation funds could come from $4 billion in drought funding included in the Inflation Reduction Act under consideration in Washington, U.S. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona told the AP.

Sinema acknowledged that paying farmers to conserve is not a long-term solution: "In the short term, however, in order to meet our day-to-day needs and year-to-year needs, ensuring that we're creating financial incentives for non-use will help us get through," she said.

Babbitt agreed that money in the legislation will not "miraculously solve the problem" and said prices for water must be reasonable to avoid gouging because most water users will take be impacted.

"There's no way that these cuts can all be paid for at a premium price for years and years," he said.

Film Academy Apologizes to Littlefeather for 1973 Oscars

Nearly 50 years after Sacheen Littlefeather stood on the Academy Awards stage on behalf of Marlon Brando to speak about the depiction of Native Americans in Hollywood films, the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences apologized to her for the abuse she endured.

The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures on Monday said that it will host Littlefeather, now 75, for an evening of “conversation, healing and celebration” on September 17.

When Brando won best actor for “The Godfather,” Littlefeather, wearing buckskin dress and moccasins, took the stage, becoming the first Native American woman ever to do so at the Academy Awards. In a 60-second speech, she explained that Brando could not accept the award due to “the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry."

Some in the audience booed her. John Wayne, who was backstage at the time, was reportedly furious. The 1973 Oscars were held during the American Indian Movement's two-month occupation of Wounded Knee in South Dakota. In the years since, Littlefeather has said she's been mocked, discriminated against and personally attacked for her brief Academy Awards appearance.

In making the announcement, the Academy Museum shared a letter sent June 18 to Littlefeather by David Rubin, academy president, about the iconic Oscar moment. Rubin called Littlefeather's speech “a powerful statement that continues to remind us of the necessity of respect and the importance of human dignity.”

“The abuse you endured because of this statement was unwarranted and unjustified,” wrote Rubin. “The emotional burden you have lived through and the cost to your own career in our industry are irreparable. For too long the courage you showed has been unacknowledged. For this, we offer both our deepest apologies and our sincere admiration.”

Littlefeather, in a statement, said it is “profoundly heartening to see how much has changed since I did not accept the Academy Award 50 years ago.”

“Regarding the Academy’s apology to me, we Indians are very patient people — it’s only been 50 years!” said Littlefeather. “We need to keep our sense of humor about this at all times. It’s our method of survival.”

At the Academy Museum event in Los Angeles, Littlefeather will sit for a conversation with producer Bird Runningwater, co-chair of the academy's Indigenous Alliance.

In a podcast earlier this year with Jacqueline Stewart, a film scholar and director of the Academy Museum, Littlefeather reflected on what compelled her to speak out in 1973.

“I felt that there should be Native people, Black people, Asian people, Chicano people — I felt there should be an inclusion of everyone," said Littlefeather. "A rainbow of people that should be involved in creating their own image.”

Native American News Roundup August 7-13, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

New Federal Group to Challenge Racist Place Names

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland has named an Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names to consult with tribes, tribal groups, state and local governments and the public to identify and recommend changes to derogatory geographic names.

Oglala Lakota tribal archaeologist Michael Catches Enemy, Niniaukapealiʻi Kawaihae of the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands and Kiana Carlson, an Ahtna Kohtaene and Taltsiine law student from the Native Village of Cantwell, are among the group established in Secretary’s Order 3405, issued in November 2021.

"Our nation’s lands and waters should be places to celebrate the outdoors and our shared cultural heritage – not to perpetuate the legacies of oppression,” Haaland said in a statement Tuesday. “The Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names will accelerate an important process to reconcile derogatory place names. I look forward to listening and learning from this esteemed group.”

To see a full list of members, click link (below).

California Wildfire, Rain, Led to Death of Thousands of Klamath River Salmon

The Karuk Tribe is blaming a 90-square-mile wildfire in northern California for the deaths of tens of thousands of fish along the Klamath River near Happy Camp, California. They believe that heavy rainfall set off a massive mudslide from the area scorched by the McKinney wildfire, which has decimated more than 233 square kilometers since July 29. The mass of debris flowed into the Klamath River, bringing water oxygen levels to zero, which caused fish to suffocate.

For years, the Karuk and Yurok tribes of northern California have fought to protect salmon, which were once abundant in most of the state’s major rivers and streams and were central to Klamath tribes’ sustenance, spirituality, and economies. But damming, water diversion and climate change have caused a drastic decline in salmon populations.

The Karuk Tribe says it’s still too early to know whether the fish kill will impact the fall migration of Chinook salmon or areas of the river downstream.

Poll: Native Americans Hit Hard by Inflation, Pandemic

A new poll shows that the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, and political and social divides of the past two years have had a disproportionate impact on Native Americans and other minority groups in the U.S.

The poll says 63% of Native Americans today face serious financial problems, compared to Black Americans (55%), Latino Americans (48%) and white Americans (38%).

The survey was a joint project of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health along with National Public Radio. It polled nearly 4,200 U.S. adults between May 16 – June 13.

“Millions of minority households across the nation are facing distinct, serious financial problems during this period, including many who are being threatened with eviction and face unsafe conditions in their neighborhoods, with few options to help,” said study co-director Robert J. Blendon, a professor of public health at Harvard’s Chan School.

Among the findings:

Thirty-nine percent of Native Americans, 32% of Black Americans, 30% of Latino Americans and 13% of Asian American adults are having trouble getting food on the table, compared to 21% of white Americans.

Twenty-five percent of Native Americans, 22% of Black Americans, 19% of Latino Americans and 14% of Asian American adults face serious challenges in paying for medical care and prescription drugs; 16% of white Americans cited similar problems with health care access.

Oregon university to offer tuition discounts to students from all federally recognized tribes

Beginning this fall, Portland State University (PSU) in Oregon will allow students from all federally recognized tribes in the U.S. to receive in-state tuition benefits. Non-resident undergraduate students normally pay $620 per credit hour. Native American student tuition will be reduced to the resident rate of $200 per credit hour.

Typically, students take 12 to 15 credits per semester. This means Native American undergraduate students will save up to $19,000 per semester.

The Postsecondary National Policy Institute in 2021 estimated that fewer than a quarter of 18-24-year-old Native Americans were enrolled in college, compared to 41% of the overall U.S. population.

PSU says it is the only U.S. school to offer tuition discounts to Native American students on a national scale. Earlier this year, the University of California system announced it would waive tuition and fees beginning in fall 2022 for all Native American students who are state residents and members of federally recognized California tribes.

Native Americans Give ‘Prey’ High Scores for Authenticity

Native American viewers and critics are applauding the newly released science fiction thriller “Prey” for the accuracy of its portrayal of Comanche life on the Great Plains in the early 18th Century.

The fifth film in the “Predator” movie franchise debuted August 5 on the North American subscription streaming platform, Hulu. It tells the story of the first-ever visit to earth by the terrifying extraterrestrial Predator and the efforts of a hatchet-wielding female warrior Naru, played by Assiniboine, Nakota, Lakota and Dakota actor Amber Midthunder, to track the creature down and destroy it. Film newcomer Dakota Beavers plays Naru's brother Taabe.

Director Dan Trachtenberg relied on a team of Comanche experts to give the film its authenticity, including producer Jhane Myers, a citizen of the Comanche Nation in Oklahoma and the Comanche Language and Cultural Preservation Committee.

Viewers on Hulu are able to watch both the English version of the film and a version dubbed in the Comanche language.

Otoe-Missouria and Choctaw journalist/blogger Johnnie Jae calls Prey “a groundbreaking achievement” for the Comanche Nation and "a rare tribute to the indigenuity [a newly-coined word which combines "indigenous" and "ingenuity"], strength, and sheer stubbornness that has allowed Native people to survive…”

Poet, writer and storyteller Cliff Taylor, a member of the Ponca Tribe in Nebraska, admits “when climatic [sic] battle was happening in the land as it was before this modern world stomped all over it, I was war-hooping unabashedly at full-blast, shaking the timbers of my house, feeling a gigantic soul-explosion of Native power, all sorts of energy and feelings coursing through my body.”

Tribe: California Wildfire Near Oregon Causes Fish Deaths

A wildfire burning in a remote area just south of the Oregon border appears to have caused the deaths of tens of thousands of Klamath River fish, the Karuk Tribe said Saturday.

The tribe said in a statement that the dead fish of all species were found Friday near Happy Camp, California, along the main stem of the Klamath River.

Tribal fisheries biologists believe a flash flood caused by heavy rains over the burn area caused a massive debris flow that entered the river at or near Humbug Creek and McKinney Creek, said Craig Tucker, a spokesman for the tribe.

The debris entering the river led to oxygen levels in the Klamath River dropping to zero on Wednesday and Thursday nights, according to readings from tribal monitors at a nearby water quality station.

A photo from the Karuk taken about 32 kilometers downstream from the flash flood in the tributary of Seiad Creek showed several dozen dead fish belly up amid sticks and other debris in thick, brown water along the riverbank.

The full extent of the damage is still unclear, but the tribe said late Saturday it appears the fish found dead 32 kilometers downstream were swept there after their deaths and that the fish kill isn’t impacting the entire river.

“We think the impact is limited to 10 or 20 miles (16 or 32 kilometers) of river in this reach and the fish we are seeing in Happy Camp and below are floating downstream from the ‘kill zone,'” the tribe said in an updated statement, adding it continues to monitor the situation.

The McKinney Fire, which has burned more than 9233 square kilometers in the Klamath National Forest, this week wiped out the scenic hamlet of Klamath River, where about 200 people lived. The flames killed four people in the tiny community and reduced most of the homes and businesses to ash.

Scientists have said climate change has made the West warmer and drier over the last three decades and will continue to make weather more extreme and wildfires more frequent and destructive. Across the American West, a 22-year megadrought deepened so much in 2021 that the region is now in the driest spell in at least 1,200 years.

When it began, the McKinney Fire burned just several hundred acres and firefighters thought they would quickly bring it under control. But thunderstorms came in with ferocious gusts that within hours had pushed it into an unstoppable conflagration.

The blaze was 30% contained Saturday.

The fish kill was a blow for the Karuk and Yurok tribes, which have been fighting for years to protect fragile populations of salmon in the Klamath River. The salmon are revered by the Karuk Tribe and the Yurok Tribe, California’s second-largest Native American tribe.

The federally endangered fish species has suffered from low flows in the Klamath River in recent years and a parasite that's deadly to salmon flourished in the warmer, slower-moving water last summer, killing fish in huge numbers.

After years of negotiations, four dams on the lower river that impede the migration of salmon are on track to be removed next year in what would be the largest dam demolition project in U.S. history to help the fish recover.

Wounded Knee Artifacts Highlight Slow Pace of Native American Repatriations

BARRE, Mass. — One by one, items purportedly taken from Native Americans massacred at Wounded Knee Creek emerged from the dark, cluttered display cases where they've sat for more than a century in a museum in rural Massachusetts.

Moccasins, necklaces, clothing, ceremonial pipes, tools and other objects were carefully laid out on white backgrounds as a photographer dutifully snapped pictures under bright studio lights.

It was a key step in returning scores of items displayed at the Founders Museum in Barre to tribes in South Dakota that have sought them since the 1990s.

"This is real personal," said Leola One Feather, of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, as she observed the process as part of a two-person tribal delegation last week. "It may be sad for them to lose these items, but it's even sadder for us because we've been looking for them for so long."

Recent efforts to repatriate human remains and other culturally significant items such as those at the Founders Museum represent significant and solemn moments for tribes. But they also underscore the slow pace and the monumental task at hand.

Some 870,000 Native American artifacts — including nearly 110,000 human remains — that should be returned to tribes under federal law are still in the possession of colleges, museums and other institutions across the country, according to an Associated Press review of data maintained by the National Park Service.

The University of California, Berkeley tops the list, followed closely by the Ohio History Connection, the state's historical society. State museums and universities in Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Alabama, Illinois and Kansas as well as Harvard University round out the other top institutions.

And that's not even counting items held by private institutions such as the Founders Museum, which maintains it does not receive federal funds and therefore doesn't fall under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, the 1990 law governing the return of tribal objects by institutions receiving federal money.

"They've had more than three decades," says Shannon O'Loughlin, chief executive of the Association on American Indian Affairs, a national group that assists tribes with repatriations. "The time for talk is over. Enough reports and studying. It's time to repatriate."

Museum officials say they've stepped up efforts with added funding and staff, but continue to struggle with identifying artifacts collected during archaeology's early years. They also say federal regulations governing repatriations remain time-consuming and cumbersome.

Dan Mogulof, an assistant vice chancellor at UC Berkeley, says the university is committed to repatriating the entire 123,000 artifacts in question "in the coming years at a pace that works for tribes."

In January, the university repatriated the remains of at least 20 victims of the Indian Island Massacre of 1860 to the Wiyot Tribe in Humboldt County, California. But its Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology still holds more than 9,000 sets of ancestral remains, mainly from Bay-area tribes.

"We acknowledge the great harm and pain we have caused Native American people," Mogulof said. "Our work will not be complete until all of the ancestors are home."

At the Ohio History Connection, officials are working to create an inter-tribal burial ground to help bury ancestral remains for tribes forced to move from Ohio as the nation expanded, says Alex Wesaw, the organization's director of American Indian relations.

The institution took similar steps in 2016 when it established a cemetery in northeast Ohio for the Delaware tribes of Oklahoma to re-bury nearly 90 ancestors who had been stored for centuries in museums in Pennsylvania.

Complicating matters, some of its more than 7,000 ancestral remains and 110,000 objects are thousands of years old, making it difficult to determine which modern-day tribe or tribes they should be returned to, Wesaw said.

At the Founders Museum, some 70 miles (112 kilometers) west of Boston, among the challenges has been determining what's truly from the Wounded Knee Massacre, says Ann Meilus, the museum's board president.

Some tribe members maintain as many as 200 items are from massacre victims, but Meilus said museum officials believe its less than a dozen, based on discussions with a tribe member more than a decade ago.

The collection was donated by Barre native Frank Root, a 19th century traveling showman who claimed he'd acquired the objects from a man tasked with digging mass graves following the massacre.

Among the macabre collection was a lock of hair reportedly cut from the scalp of Chief Spotted Elk, which the museum returned to one of the Lakota Sioux leader's descendants in 1999. It also includes a "ghost shirt," a sacred garment that some tribe members tragically believed could make them bulletproof.

"He sort of exaggerated things," Meilus said of Root. "In reality, we're not sure if any of the items were from Wounded Knee."

More than 200 men, women, children and elderly people were killed on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in 1890 in one of the country's worst massacres of Native Americans. The killings marked a seminal moment in the frontier battles the U.S. Army waged against tribes.

The U.S. Department of Interior recently proposed changes to the federal repatriation process that lay out more precise deadlines, clearer definitions and heftier penalties for noncompliance.

Tribe leaders say those steps are long overdue, but don't address other fundamental problems, such as inadequate federal funding for tribes to do repatriation work.

Many tribes also still object to requirements that they explain the cultural significance of an item sought for repatriation, including how they're used in tribal ceremonies, says Brian Vallo, a former governor of the Pueblo of Acoma in New Mexico who was involved in the 2020 repatriation of 20 ancestors from the National Museum of Finland and their re-burial at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado.

"That knowledge is only for us," he said. "It's not ever shared."

Stacy Laravie, the historic preservation officer for the Ponca Tribe in Nebraska, is optimistic museum leaders are sincere in seeking to rectify the past, in the wake of the national reckoning on racism that's reverberated through the country in recent years.

Last month, she traveled with a tribal delegation to Harvard to receive the tomahawk of her ancestor, the Native American civil rights leader Chief Standing Bear. She's also working with the university's Peabody Museum to potentially repatriate other items significant to her tribe.

"We're playing catch up from decades of things getting thrown under the rug," Laravie said. "But I do believe their hearts are in the right place."

Back at the Founders Museum, Jeffrey Not Help Him, an Oglala Sioux member whose family survived the Wounded Knee Massacre, hopes the items could return home this fall, as the museum has suggested.

"We look forward to putting them in a good place," Not Help Him said. "A place of honor."

Navajo Code Talker Samuel Sandoval Dies; 3 Code Talkers Remain

Samuel Sandoval, one of the last remaining Navajo Code Talkers who transmitted messages in World War II using a code based on their native language, has died.

Sandoval died late Friday at a hospital in Shiprock, New Mexico, his wife, Malula, told The Associated Press on Saturday. He was 98.

Hundreds of Navajos were recruited from the vast Navajo Nation to serve as Code Talkers with the U.S. Marine Corps. Only three are still alive today: Peter MacDonald, John Kinsel Sr. and Thomas H. Begay.

The Code Talkers took part in every assault the Marines conducted in the Pacific, sending thousands of messages without error on Japanese troop movements, battlefield tactics and other communications critical to the war's ultimate outcome. The code, based on the then-unwritten Navajo language, confounded Japanese military cryptologists and is credited with helping the U.S. win the war.

Samuel Sandoval was on Okinawa when he got word from another Navajo Code Talker that the Japanese had surrendered and relayed the message to higher-ups. He had a close call on the island, which brought back painful memories that he kept to himself, Malula Sandoval said.

The Navajo men are celebrated annually on Aug. 14. Samuel Sandoval was looking forward to that date and seeing a museum built near the Navajo Nation capital of Window Rock to honor the Code Talkers, she said.

"Sam always said, 'I wanted my Navajo youngsters to learn, they need to know what we did and how this code was used and how it contributed to the world,'" she said Saturday. "That the Navajo language was powerful and always to continue carrying our legacy."

Sandoval was born in Nageezi near Chaco Culture National Historical Park in northwestern New Mexico. He enlisted in the Marine Corps after attending a Methodist school where he was discouraged from speaking Navajo. He helped recruit other Navajos from the school to serve as Code Talkers, expanding on words and an alphabet that an original group of 29 Navajos created.

Sandoval served in five combat tours and was honorably discharged in 1946. The Code Talkers had orders not to discuss their roles — not during the war and not until their mission was declassified in 1968.

The roles later became an immense source of pride for Sandoval and his late brother, Merrill Sandoval, who also was a Code Talker. The two became talented speakers who always hailed their fellow Marines still in action as the heroes, not themselves, said Merrill Sandoval's daughter, Jeannie Sandoval.

"We were kids, all growing up and we started to hear about the stories," she said. "We were so proud of them, and there weren't very many brothers together."

Samuel Sandoval often told his story, chronicled in the documentary Naz Bah Ei Bijei: Heart of a Warrior at the Cortez Cultural Center in Cortez, Colorado, said executive director Rebecca Levy.

Sandoval's health had been declining in recent years, including a fall in which he fractured a hip, Malula Sandoval said. His last trip was to New Orleans in June where he received the American Spirit Award from the National World War II Museum, she said. MacDonald, Kinsel and Begay also were honored.

Sandoval and his wife met while he was running a substance abuse counseling clinic, and she was a secretary, she said. They were married 33 years. Sandoval has six children from previous marriages.

Navajo President Jonathan Nez said Sandoval will be remembered as a loving and courageous person who defended his homeland using his sacred language.

"We are saddened by his passing, but his legacy will always live on in our hearts and minds," Nez said in a statement.

Navajo Nation Council Speaker Seth Damon said Sandoval's life was guided by character, courage, honor and integrity, and his impact will forever be remembered.

"May he rest among our most resilient warriors," Damon said in a statement.

There’s a Maternal Health Care Crisis in America

Black women and Native American women are more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women in America, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vice President Kamala Harris has made maternal health a key piece of her domestic policy agenda. For Wanda Irving, whose daughter died after giving birth, a national response can’t come fast enough. VOA’s Laurel Bowman has the story. Camera: Saqib Ul Islam, Adam Greenbaum, Mike Burke

Tim Giago, Trailblazing Native American Journalist, Dies

Tim Giago, the founder of the first independently owned Native American newspaper in the United States, has died at age 88, his former wife said.

Giago, who died at Monument Health in Rapid City, South Dakota, on Sunday, created an enduring legacy during his more than four decades of work in South Dakota journalism, his colleagues said.

Giago, who was a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe, founded The Lakota Times with his first wife, Doris, in 1981, and quickly showed that he wasn't afraid to challenge those in power and advocate for American Indians, she said.

Launching the paper, even years after the 1973 Wounded Knee siege between U.S. marshals and the Native American Movement, was challenging because wounds still existed on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and in South Dakota, Doris Giago said.

Tim Giago blamed the American Indian Movement for violence on the reservation. Windows at the paper were broken and the office was firebombed.

"And through it all, Tim never backed down," said Doris Giago, who was married to him from 1979 to 1986.

The Lakota Times was eventually renamed Indian Country Today, and later became ICT. In a July 2021 interview with the paper, Giago recounted that tense period and "some of the hard things that came out of work."

"One night got in my pickup and somebody put a bullet through my windshield and just missed my head," Giago told the newspaper. "So, I mean, if that's what it took to get the freedom of the press going on the reservation, I guess that's what it took."

Giago, a 1991 Nieman Fellow at Harvard University, wrote years later that while he was working as a reporter for the Rapid City Journal, he was bothered by the fact that although he had been born and raised on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, he was seldom given an opportunity to do news stories about the people of the reservation.

"One editor told me that I would not be able to be objective in my reporting. I replied, 'All of your reporters are white. Are they objective when covering the white community?"'

The Giagos started the Lakota Times in a former beauty shop on the reservation, with no real training on the business side of newspapering, Doris Giago recalled.

"They gave us six months to succeed. They didn't think we would last after that. We learned from our mistakes," she said.

In 1992, he changed the paper's name to Indian Country Today to reflect its national coverage of Native American news and issues. He sold the paper to the Oneida Nation in 1998.

Two years later he founded The Lakota Journal and in 2009, he founded the Native Sun News, based in Rapid City, South Dakota.

"He always pushed for more, reaching for an even better way to serve Native American people with news. So, after Lakota Times it was Indian Country Today. Then Lakota Journal. Then Native Sun News. He never lost his vision about how important it is for a community to have a journalistic recording of itself," said Mark Trahant, ICT's editor-at-large.

Giago founded the Native American Journalists Association and served as its first president. He was also the first Native American to be inducted into the South Dakota Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Even though Giago's work had critics, they still respected him "for doing his job and protecting Native people," ICT's editor Jourdan Bennett-Begaye said.

"Nothing could stop him. What I really admired about him was his fearlessness," she said.

Survivors include his wife, Jackie Giago; a sister, Lillian; 12 children and numerous grandchildren. Funeral arrangements were pending.