Native Americans

Native American News: 2022 in Review

Here is a summary of some of the top Native American-related stories in 2022.

Native Americans Scored Big Wins in Midterm Vote

2022 saw a record number of Native American/Alaska Native political candidates running for federal, state and local office in midterm elections November 8. Out of 150 candidates, more than 85 won at the ballot box, among them:

- Republican Markwayne Mullin, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, won a seat in the U.S. Senate

- Democrat Mary Peltola, Yup'ik from Western Alaska, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives

- Democrat Sharice Davids, Ho-Chunk from Kansas, won a third term in the U.S. House of Representatives

Republican Tom Cole, Chickasaw from Oklahoma, won an 11th term in the U.S. House of Representatives

In June, President Joe Biden nominated Chief Mutáwi Mutáhash (“Many Hearts”) Marilynn “Lynn” Malerba, the lifetime chief of the Mohegan Indian Tribe in Connecticut, to serve as U.S. treasurer. She now oversees the U.S. Mint, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and Fort Knox, home of the U.S. gold reserves, and is a key liaison with the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank.

In December, Malerba and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen became the first pair of women to sign a newly minted $5 bill.

Read more:

Supreme Court Cases Seen as Threats to Tribal Sovereignty

President Joe Biden this year reiterated his commitment to the sovereignty of Native American tribes, nations and communities. He also injected historic levels of funding into Indian Country and gave tribes a greater voice in policy and decision-making.

Even so, tribes in 2022 expressed fears that their sovereignty was under threat after the June U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Castro v. Huerta, which expanded state authority to prosecute non-Indians who commit crimes against Indians on tribal land. Formerly, only federal and tribal courts had legal jurisdiction in such cases.

In November, Supreme Court justices heard oral arguments in Brackeen v. Haaland, a lawsuit challenging the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), a 43-year-old federal law that sought to curb the once widespread practice of removing Native American children from their families and placing them in non-Native homes and institutions.

ICWA instructs welfare agencies to give preference to placing Indian children with relatives or with fellow tribe members.

ICWA opponents argue that the law is unconstitutional because it discriminates against non-Native adoptive or foster parents. They also argue that Congress has overstepped its authority by legislating matters that should be the “exclusive province of the States.”

Native American rights groups fear that a defeat of ICWA could upend other areas of tribal law. ICWA has a severability clause, which means that some parts of the law could be struck down and the remaining parts of the law could remain intact.

Justices are expected to issue a decision in June or July 2023.

Read more:

Feds Acknowledge, Investigate Indian Boarding School Abuses

In May, the U.S. Interior Department released the first volume of a federal probe into the Indian boarding school program.

Ordered by Secretary Deb Haaland, a citizen of the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, the investigation found that between 1819 and 1969, the federal government “operated or supported” 408 boarding schools in 37 states or former territories, including 21 in Alaska and seven in Hawaii. The report counted 500 student deaths and discovered graves at 53 schools; those numbers are expected to rise as the probe continues.

The report recommended further research into federal boarding school abuses, investigations into tribal health disparities and support for Indigenous language revitalization programs.

In July, Haaland and Assistant Treasury Secretary Bryan Newland launched a yearlong “Road to Healing Tour,” traveling to Oklahoma, Michigan and South Dakota to give boarding school survivors and their families a chance to tell their stories, to help connect communities with trauma support and to begin work on collecting a permanent oral history. Haaland conducted listening sessions in Anadarko, Oklahoma; Pellston, Michigan; and Mission, South Dakota, and plans visits to other states in 2023.

While she was serving in Congress, Haaland introduced legislation to establish a truth and healing commission to investigate and document Indian boarding school abuses and their impact on tribes and families. It was reintroduced in 2022 by Representative Sharice Davids. Senator Elizabeth Warren introduced a similar bill in the Senate.

The House bill got its first hearing May 12.

While there appears to be broad support for a commission, lawmakers are divided on whether and/or how much authority it should have to subpoena witnesses, records and documents, how the commission would be funded and whether members would be compensated for their time.

Read more:

Haaland Erases Slurs from US Map

In November, Secretary Haaland signed Secretarial Order 3404, declaring “sq---,” a historic term for Native American women, to be derogatory and setting up a task force to remove the word from 650 geographic features across the U.S.

Throughout the year, the department consulted with almost 70 tribes and announced in September an agreement on new names.

See the new names here:

See a map of locations here:

Native Talent Reshifting the Narrative in Film and Television

2022 was a watershed year for Indigenous representation in film and television.

This year saw Season 2 of “Reservation Dogs,” a comedy drama about teens living on an Oklahoma reservation. The first TV series ever to feature all-Indigenous writers and directors and an almost entirely North American Indigenous cast, it won an impressive number of awards.

“Dark Winds,” a crime drama set in the Navajo Nation and starring veteran Lakota actor Zahn McClarnon, was shot at the first Indigenous-owned film studio in New Mexico.

The summer film hit “Prey,” a prequel to Disney’s “Predator” series, starred a mostly Native American cast and was released in English and Comanche language versions.

Read more:

Law Protects Export of Sacred Native American Items From US

Federal penalties have increased under a newly signed law intended to protect the cultural patrimony of Native American tribes, immediately making some crimes a felony and doubling the prison time for anyone convicted of multiple offenses.

President Joe Biden signed the Safeguard Tribal Objects of Patrimony Act on December 21, a bill that had been introduced since 2016. Along with stiffer penalties, it prohibits the export of sacred Native American items from the U.S. and creates a certification process to distinguish art from sacred items.

The effort largely was inspired by pueblo tribes in New Mexico and Arizona who repeatedly saw sacred objects up for auction in France. Tribal leaders issued passionate pleas for the return of the items but were met with resistance and the reality that the U.S. had no mechanism to prevent the items from leaving the country.

"The STOP Act is really born out of that problem and hearing it over and over," said attorney Katie Klass, who represents Acoma Pueblo on the matter and is a citizen of the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma. "It's really designed to link existing domestic laws that protect tribal cultural heritage with an existing international mechanism."

The law creates an export certification system that would help clarify whether items were created as art and provides a path for the voluntary return of items that are part of a tribe's cultural heritage. Federal agencies would work with Native Americans, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians to outline what items should not leave the U.S. and to seek items back.

Information provided by tribes about those items would be shielded from public records laws.

While dealers and collectors often see the items as art to be displayed and preserved, tribes view the objects as living beings held in the community, said Brian Vallo, a consultant on repatriation.

"These items remain sacred, they will never lose their significance," said Vallo, a former governor of Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico. "They will never lose their power and place as a cultural item. And it is for this reason that we are so concerned."

Tribes have seen some wins over the years:

— In 2019, Finland agreed to return ancestral remains of Native American tribes that once called the cliffs of Mesa Verde National Park in southern Colorado home. The remains and artifacts were unearthed by a Swedish researcher in 1891 and held in the collection of the national Museum of Finland.

— That same year, a ceremonial shield that vanished from Acoma Pueblo in the 1970s was returned to the tribe after a nearly four-year campaign involving U.S. senators, diplomats and prosecutors. The circular, colorful shield featuring the face of a Kachina, or ancestral spirit, had been held at a Paris auction house.

— In 2014, the Navajo Nation sent its vice president to Paris to bid on items believed to be used in wintertime healing ceremonies after diplomacy and a plea to return the items failed. The tribe secured several items, spending $9,000.

—In 2013, the Annenberg Foundation quietly bought nearly two dozen ceremonial items at an auction in Paris and later returned them to the Hopi, the San Carlos Apache and the White Mountain Apache tribes in Arizona. The tribes said the items invoke the spirit of their ancestors and were taken in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

The STOP Act ties in with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act that requires museums and universities that receive federal funds to disclose Native American items in their possession, inventory them, and notify and transfer those items to affiliated tribes and Native Hawaiians or descendants.

The Interior Department has proposed several changes to strengthen NAGPRA and is taking public comment on them until mid-January.

The STOP Act increases penalties for illegally trafficking Native American human remains from one year to a year and a day, thus making it a felony on the first offense. Trafficking cultural items as outlined in NAGPRA remains a misdemeanor on the first offense. Penalties for subsequent offenses for both increase from five years to 10 years.

New Mexico U.S. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez, who introduced the House bill, said time will tell whether the penalties are adequate.

"We should always look at the laws we pass as not static but as living laws, so we are able to determine improvements that can be made," she said.

Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, the former cultural preservation director for the Hopi Tribe, said the enhanced penalties are helpful. But he wants to see countries embrace a principle of mutual respect and deference to the laws of sovereign Native American nations when it comes to what's rightfully theirs. For Hopi, he said, the items are held by the community and no one person has a right to sell or give them away.

The items can be hard to track but often surface in underground markets, in museums, shows, and auction house catalogs, Vallo said.

He said Finland, Germany and the U.K. shared intentions recently to work with U.S. tribes to understand what's in their collections and talk about ways to return items of great cultural significance.

"I think if we can make some progress, even with these three countries, it sends a strong message that there is a way to go about this work, there is a mutual reward at the end," he said. "And it's the most responsible thing to be engaged in."

Native American News Roundup Dec. 18-24, 2022

Here is a summary of Native American-related headlines in the U.S. this week:

Winter storm blasts Rosebud Indian Reservation

The Rosebud Indian Reservation in south central South Dakota was crippled this week by a storm system that brought record snow, high winds and dangerously cold temperatures.

Major highways in South Dakota reopened, but local media reported that some commercial trucks remained stuck in snow drifts.

CBS affiliate KELOLAND TV Tuesday reported that Rosebud officials said five people had died and more than 100 families had run out of propane to heat their homes.

“My niece’s family, with babies all six years old and under, have been running high fevers and ran out of supplies,” tribe member Evelyn Red Lodge told VOA from her home in Rapid City, about 300 kilometers away from the reservation. “Their uncles are walking supplies to them in dangerous wind chills far from the main road.”

An estimated 20,000 residents live on Rosebud, which spans just over 5,100 square kilometers in the Great Plains.

Facing a shortage of snow removal equipment, the tribe has had to rely on community members to check on elders, shovel snow and share food and supplies.

“I sat with an unresponsive, critical diabetic patient here at the apartments on the third day of the storm for six hours while emergency personnel fight to get here,” said Conrad Eagle Feather in the town of Mission. “We have people trying to walk for supplies, 10 to 15 miles (16 to 24 kilometers) one way.”

Rosebud tribal president Scott Herman issued a statement on Facebook saying he had called on federal and state authorities to help provide personnel and equipment.

In response to complaints that the state wasn’t doing enough to help, South Dakota’s Department of Public Safety issued a press release outlining services it has provided tribes since last week. These included sending two snow loaders to Rosebud and coordinating with the state transportation agency to deliver propane, firewood, and food.

Read more:

Native American Church to Washington: Help save our peyote

Native American Church leaders say that increased land and resource development in Texas has taken a toll on the quality and quantity of the hallucinogenic peyote cactus and have called on Washington lawmakers for help.

Peyote is a succulent that contains psychoactive alkaloids. It only grows in southern Texas and a handful of states in northern Mexico.

As VOA has reported previously, Indigenous people have used it ceremonially and medicinally for centuries.

Peyote was banned in the United States in 1970, but the law was later amended to allow its use in religious ceremonies of the Native American Church.

Medical researchers cite growing evidence that psychedelics like peyote can help treat depression and other mental disorders. Two California cities have called for it to be legalized, and in November, Colorado decriminalized some psilocybin-containing drugs.

The Native American Church worries that legalizing these drugs will only further threaten peyote harvests. At an October listening session, Church leaders asked the U.S. government to help fund peyote habitat preservation programs and change language in the Farm Bill to give farmers incentives to alter the ways they clear brush for cattle grazing.

Read more:

North Dakota tribe works to raise awareness about organ donations

Inspired by a young tribe member who received an artificial heart, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians in Belcourt, North Dakota, has added an organ donation box to tribal identification cards.

A 2014 study in the Journal of Community Health said that the rate of organ donations among American Indians and Alaska Natives is lower than other U.S. racial or ethnic population in the country. The groups suffer disproportionately high rates of kidney disease, for which transplants are often the best treatment.

Study authors say the low rates of organ donation are due in part to traditional beliefs and burying practices, as well as mistrust in the health care system.

Read more:

Native Americans slam Avatar 2 film as racist

Native American groups are calling for a boycott of the recently released “Avatar: The Way of Water,” a science fiction film the Los Angeles Times describes as a “fictional retelling of the history of North and South America in the early Colonial period.”

The sequel to the 2009 hit “Avatar” tells the story of a Na’vi family, the Sullys, who live on a fictional moon, Pandora. Humans have invaded and colonized Pandora because their planet Earth is dying. The family is displaced from its home and flees in exile to the underwater world of another tribe, the Metkayina.

“Europe equals Earth,” the Times quotes director James Cameron from a 2010 interview. “The Native Americans are the Na’vi. It’s not meant to be subtle.”

In the 2010 interview, Cameron said the Avatar franchise was inspired by the Lakota, whom he called a “dead end society” that should have fought harder against colonization.

Read more:

Native American News Roundup Dec. 11-17, 2022

Here is a summary of some of the top Native American-related news stories this week:

Biden to Sign Bill Repealing Archaic Indian Laws

The House of Representatives has passed legislation to repeal 11 obsolete federal laws that are discriminatory to Native Americans. Among them is an 1847 law giving agents permission to withhold money and goods from any Indians possessing or under the influence of alcohol.

Another 1893 law allowed the Interior secretary to withhold rations, money, and other benefits from Native American parents or guardians who refused to send their children to school.

Republican Senator Mike Rounds first introduced the Repealing Existing Substandard Provisions Encouraging Conciliation with Tribes (RESPECT) Act in 2019.

“Throughout history, Native Americans have been subjected to unfair treatment from our federal government, including the forced removal of their children from their homes,” Rounds said. “Clearly, there is no place in our legal code for such measures, and it is appalling these laws are still in our federal code. I am pleased this bipartisan, commonsense legislation is heading to the president’s desk to be signed into law.”

Read more:

Michigan Tribes Sign Great Lakes Fishing Rights Deal

Four Native American tribes have reached a deal with state and federal officials on a revised fishing policy for areas of Lakes Michigan, Huron and Superior that were ceded by tribes in an 1836 treaty in exchange for hunting and fishing rights.

The proposal sets zones where tribal fishing crews would be allowed to operate and areas where commercial fishing would be banned.

Tensions between tribal commercial fishing operations and sports fishermen led to a fishery management pact in 1985. It was updated in 2000 but was set to expire.

The Bay Mills Indian Community, the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians and the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians have all signed on to the deal, which would extend the pact for another 24 years. It has now been sent to a federal judge for approval.

“We've reached an agreement that's consistent with what's been in place for 37 years but reacts to a changed fishery,” Grand Traverse Band attorney Bill Rastetter said. “It won't create any burden on state-licensed fishers. The harvest limits will remain in place.”

Read more:

South Dakota Prosecutors Drop all Charges Against Lakota Activist

The state of South Dakota has dropped all charges against the head of an Indigenous-led advocacy organization who was arrested during protests against then-President Donald Trump’s visit to Mount Rushmore in 2020, the group announced Tuesday.

NDN Collective president Nick Tilsen was charged with robbery and the assault of a police officer after allegedly taking a shield from a National Guard soldier.

Tilsen said in a statement that the dismissal of charges shows they were “bogus from the start,” and “fueled by white fragility and fear of Indigenous power.”

Court documents show that the charges were dismissed nearly a month ago. So why did Tilsen wait so long to announce it?

“Last time we had a deal, the state prosecutor’s office pulled it after we talked to the media,” he told VOA via email. “We waited a few weeks before going public this time.”

Read more:

Native Student Wins Right to Appeal First Amendment Rights Lawsuit

A federal appeals court has revived a First Amendment lawsuit brought by a Native American student who says she was banned from attending her 2019 high school graduation ceremony because she had decorated her cap with beading and an eagle feather, a symbol sacred to Native Americans.

Larissa Waln, a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate of South Dakota, said the Dysart, Arizona, school district violated her right to free speech and free exercise of religion, while it allowed another student to wear a “breast cancer awareness” sticker on his graduation cap.

In reviving Waln’s suit, a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit in San Francisco acknowledged Native Americans have a long history of wearing eagle feathers “in times of great honor.”

“Plaintiff adequately has alleged that the District violated her First Amendment rights to the free exercise of religion and to the freedom of speech,” ruled the judge. “Whether Plaintiff can prove her claims is not before us. But the district court erred by dismissing her complaint.”

Read more:

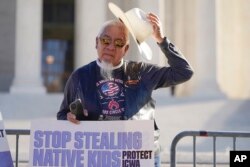

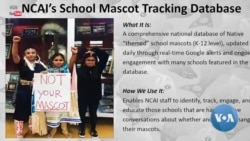

Native Activists on Mascots: Retire Offensive School Mascots

Twenty-one states are considering or have banned altogether Native American-themed mascots from public schools. New York is the latest. But school districts across the country still use Native mascots, and activists say that banning them is long overdue. VOA’s Veronica Balderas Iglesias has our story:

Native American News Roundup Dec. 4-10, 2022

Here is a summary of some of the top stories related to Native Americans this week:

Senate passes bill to lock stolen Indigenous artifacts inside U.S. borders

The U.S. Senate has approved legislation criminalizing the theft, trafficking and export of illegally obtained Native American, Native Alaskan or Native Hawaiian remains and ceremonial objects.

H.R.2930, the Safeguard Tribal Objects of Patrimony Act of 2021 (STOP Act), supplements the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which banned the trafficking of Indigenous remains, funerary and sacred artifacts.

The bill does not ban the general trade in Native art and artifacts made for commercial purposes. But it does ban the export of sacred items stolen from tribal land.

“There is a clear difference between supporting American Indian art ethically and legally as opposed to dealing or exporting items that tribes have identified as essential and sacred pieces of their cultural heritage,” said Democratic Senator Martin Heinrich, who with Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski has pushed this bill since 2016.

The new measure also increases from five years to 10 years the maximum prison term for violators.

Read more:

Study shows restoring Indigenous fire practices could thwart climate-Induced wildfires

A new study led by Southern Methodist University suggests that the Indigenous practice of setting small, controlled fires to revitalize wildfire-prone lands could help mitigate effects of climate change that contribute to wildfires.

A research team including four members of federally recognized tribes studied “cultural burning” through a network of more than 4,800 fire-scarred trees in Arizona and New Mexico, homelands of the Apache, Navajo and Jemez tribes.

Over a 400-year period, the study found that the typical climate-fire pattern includes one to three years of above-average rainfall — which allows vegetation to grow — followed by a fire-fueling year of significant drought. But when Native American tribes conducted controlled burns, that pattern was broken.

The report comes just a week after the Biden administration announced the first-ever government-wide guidance for federal agencies to recognize and include Indigenous knowledge in federal research, policy and decision-making.

Read more:

California tribes to Interior Department: Save our fish

The Center for Biological Diversity and the Pomo Tribes of California are calling on Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to use her emergency powers to invoke the federal Endangered Species Act on behalf of the hitch minnow, a fish that the Pomo call “chi.”

For thousands of years, the fish was central to the Pomo people’s diet and culture in the Clear Lake area of Northern California. Today, climate change, drought, pollution and predatory non-native fish have radically diminished the hitch minnow population.

“I remember catching chi as a young boy and now can only hope that my children will one day have that same experience,” said Jesse Gonzalez, vice chair of Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians. “If the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service doesn’t give the chi emergency endangered species protections, we fear that our future generations will never have that opportunity.”

Read more:

Honors may be due Native Americans who fought in World War I

A team of researchers and historians is looking for Native American and Alaska Native soldiers who served in World War I who may be eligible for posthumous valor medals.

The University of Arkansas at Little Rock’s Sequoyah National Research Center is working with the George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War at Park University in Missouri. Together, they have identified about 12,000 Native Americans who served between 1914 and 1921.

To qualify for a review of what, if any, other medals they might be due, service members must have received a Distinguished Service Cross/Navy Cross and/or the French Croix de Guerre with Palm or have been recommended for a Medal of Honor but were downgraded.

So far, the research team has identified two dozen Native Americans who qualify for a case review. That list includes Alaska Natives but no Native Hawaiians.

“We have worked on the Modern Warriors of World War I database since 2017 and have yet to find any Native Hawaiians who served,” University of Arkansas archivist Erin Fehr told VOA.

More than 9,800 Hawaii residents served in World War I, according to a 1998 report by Hawaiian statistician Robert C. Schmitt. One hundred and two lost their lives.

Read more:

Search service members names or add a name to the list here:

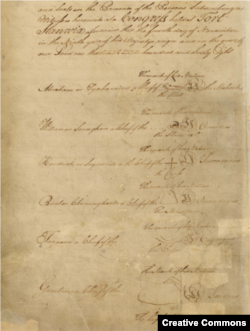

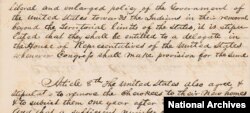

Historic land deed shows Haudenosaunee traded Pittsburgh for cloth, weapons and tobacco

A 275-year-old document recently discovered in a rural Virginia courthouse sheds new light on how easily Native Americans were dispossessed of their land.

A James Madison University graduate student digitizing historic records held in the Augusta County, Virginia, courthouse discovered a 1749 deed showing that the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and its surrounding 60,000 hectares were purchased from six leaders of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy for cloth, clothing, blankets, guns, tobacco and four dozen mouth harps — small brass musical instruments held against the teeth and plucked to create a melody.

Read more:

See original deed:

Native American Tribe Searches for Remains at California Construction Site

A Native American tribe in Northern California is racing toward a Friday deadline to conclude its search for human remains and cultural artifacts on what was once a tribal village site but will soon be home to a shared-use path and parking area.

Ancestors of the Wintu Tribe of Northern California were buried near the site, and tribal leaders said they didn't receive proper notification about construction plans from the Federal Highway Administration, which is in charge of the project.

The construction, which began in July, will create a 3,900-foot (1,190-meter) path, a parking area and restroom facilities near Redding, a small California city about 120 miles (190 kilometers) south of the Oregon border. It will be located off Interstate 5, one of the state's major north-south roads, with the path running along the Sacramento River. The project is a partnership among the highway administration, Redding and the Bureau of Land Management.

The Federal Highway Administration shared with The Associated Press a copy of the 2019 letter it says it sent to tribal leaders. But officials with the tribe say they never received a copy of it, nor any follow-up, before construction began. Federal law requires tribal consultation, and state law requires a review of whether a project could affect tribal cultural resources before proceeding with the construction of trails, highways, streets and other public areas.

City officials in Redding also sent the tribe a letter in September 2019 outlining the project and asking the tribe to respond within 30 days if it wanted to request consultation. Records provided by the city show Gary Rickard, the tribe's chairman, signed for the letter's delivery.

The dispute over whether the tribe was properly consulted comes as the Biden administration has pledged to make sure Native Americans have a stronger voice in decisions made by federal agencies.

"I made a commitment that my administration would prioritize and respect nation-to-nation relationships, and I'm going to make sure that happens," President Joe Biden said at a recent White House Tribal Nations Summit.

The Wintu Tribe of Northern California was originally made up of nine bands that historically have the Penutian language family in common. Today, the tribe has about 450 citizens, said Secretary Cindy Hogue.

The tribe first became aware of the trail construction through Robert Garcia, a monitor and tribal citizen who was walking near the site one day in August, said his niece Shawna Garcia, a council member-elect for the tribe.

In late October, Art Garcia, the tribe's cultural resources manager, found a bone fragment in the soil, and the county coroner's office was notified so an investigator could review whether it was human, the sheriff's department said in a release. The remains were deemed too small to be identifiable, the department said.

The federal government agreed to grant Art Garcia and other monitors about 1,000 hours to sift through the site for remains and artifacts.

So far, the team has found arrowheads, mortars and pestles, among other items, Shawna Garcia said. There were originally 12 monitors searching for remains and artifacts, and there were nine as of Tuesday, she said.

She said it's frustrating that the team is "still cleaning up a mess that" was a result of construction, referring to the sifting that remains to be done.

More possible remains have been found, and the coroner's office has ruled them nonhuman animal remains or indeterminate fragments. Hailey Collord-Stalder, a county deputy coroner investigator, said she last reviewed possible remains in early November.

Rickard, the tribe's chair, said the lack of early communication between the Federal Highway Administration and the tribe is uncommon compared with other talks between the tribe and governmental agencies, he said. The government should have been able to tell the risk of disturbing remains, Rickard added.

"You don't have to be an archaeologist to go out there and look and realize, oh, man, yeah, this is a village site," he said. "And when you have a village, people pass away and they bury them."

Construction halted in the area where the bone fragment was first found and temporarily at the end of the trail but was ongoing elsewhere, a highway administration spokesperson said.

The Federal Highway Administration's 2019 letter stated the tribe had 30 days to respond with information about cultural resources within the project site. The agency addressed it to former chair Wade McMasters, who had already left the job.

"Please inform us if your Tribe has a religious or cultural affiliation to resources that have been identified" in the project area, it reads. "Your knowledge of the area is of great value and your feedback is important."

Before construction began, a federally qualified archaeologist surveyed the location where the project was being proposed, the agency spokesperson said. And in June 2020, the city of Redding signed a document indicating that the agency was exempt from portions of a state law that requires agencies to assess whether projects could threaten resources including those of cultural significance to tribes.

The document says the "project has no potential to have a significant effect on the environment."

Even though the tribe isn't federally recognized, agencies are still required by state and federal law to contact them before beginning construction on a project like this, since they are considered a stakeholder, said Mark Hylkema, an archaeologist for the Santa Cruz district of California State Parks.

Agencies should also make multiple attempts to contact tribes if they don't get a response, including making phone calls, he said.

"It's good policy, and any agency knows that," Hylkema said.

The Federal Highway Administration may give the tribe more time to search through the remains, but construction of the trail is expected to wrap later this month, the spokesperson said.

Despite their frustrations, Art Garcia said, his team won't stop searching with the time they have left.

"We're not going to give up," he said.

Native American News Roundup Nov. 27-Dec. 3, 2022

Here is a summary of some of the top Native American-related headlines in the U.S. this week:

Administration Makes New Commitments At Tribal Nations Summit

President Joe Biden underscored an all-of-government commitment to Native Americans, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians during a two-day White House Tribal Nations Summit in Washington this week.

“On my watch, we're ushering in a new era of advancing a way for the federal government to work with tribal nations,” Biden told more than 300 tribal leaders at the first in-person summit of his presidency.

The Biden administration announced new programs and initiatives to boost tribal economies, restore tribal homelands, improve infrastructures and the health and safety of tribal citizens, including:

- Developing uniform guidance for federal agencies on consulting with tribes and incorporating Indigenous knowledge into federal decision-making.

- Boosting tribal co-stewardship of public lands, waters and sacred sites.

- Relocating 11 tribal communities threatened by rising water levels.

- Implementing new rules and policies to protect tribal interests and resources from the impacts of mining.

“Too often in Native history, tribal displacements, forced relocations and other tragedies were driven by the expansion of mining. We must acknowledge and remedy these injustices as our nation considers expanding domestic mining in order to produce the minerals that are necessary for current technologies and clean energy projects,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland told tribal leaders.

The administration announced Thursday that the FBI and the Bureau of Indian Affairs have signed an agreement to establish guidelines for handling criminal investigations in Indian Country, a move that Associate Attorney General Vanita Gupta said will advance investigations “including reports of missing or murdered Indigenous people, quickly, effectively and respectfully.”

President Biden said he has also asked Congress for significant increases in funding, including:

- $9.1 billion for the Indian Health Service, which provides health care to federally recognized tribes.

- $420 million for the Bureau of Indian Education, which provides education to Indian youth.

- $7 million for the Federal Boarding School Initiative, an investigation into the troubled legacy of federal Indian boarding schools.

- $35 million for culturally specific Violence Against Women Act program services.

Read more:

Study Shows Native American Homebuyers Less Likely to Get Loans Approved

A new analysis of fairness in lending shows that despite nationwide laws prohibiting racial bias, financial institutions are persistently unfair to Native Americans looking to buy new homes.

Researchers at FairPlay AI analyzed more than 350 million mortgage applications from 1990 to 2021 via the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act database to measure whether and how mortgage fairness in the U.S. has changed over the past three decades.

Using a control group of white male borrowers, researchers used the industry standard Adverse Impact Ratio metric to compare the approval rates for Black, female, Hispanic, Asian and Native American loan applicants.

In the metric, if protected class applicants had a 60% loan approval rate and white males had a 90% approval rate, the AIR would be 60/90, or 67%. FairPlay AI considers any AIR less than 80% to be an indicator of unfair lending.

Study results show a steep decline in mortgage fairness for Native Americans with a drop from 94.8 percent in 1990 to 81.9% in 2001. The study found that five states have been “persistently unfair” to Native American loan applicants: New Mexico, Mississippi, Louisiana, North Carolina and Arizona.

Read more:

Virginia Tribes Receive State Grants to Buy and Preserve Ancestral Forestlands

Two federally recognized tribes are getting state grants toward the purchase and preservation of forestlands lost to English settlers in the 17th century in what is now Virginia.

The Virginia Land Conservation Fund awarded the Rappahannock Tribe of Virginia $500,000 to acquire more than 280 hectares acres of land adjacent to the 160 hectares it successfully acquired in April along the Rappahannock River’s Fones Cliffs. Prior to contact with the English, the Rappahannock Tribe lived in at least three villages on the Cliffs -- Wecuppom, Matchopick and Pissacoack.

The state fund awarded the Mattaponi Indian Tribe $310,000 to acquire more than 320 hectares in King William County.

There is a catch, however. The grants won’t cover the full price of the land, and the tribes have two years to raise the remaining funds themselves.

Read more:

Cherokee Fourth-grader Lights Up US Capitol Christmas Tree

Catcuce “Coche” Micco Tiger, a 9-year-old citizen of the Eastern Cherokee Nation in North Carolina, helped House Speaker Nancy Pelosi light the U.S. Capitol Christmas Tree on Tuesday evening.

The fourth-grader won that honor with a winning essay that included a traditional Cherokee story on the sacredness of evergreens.

“When all the trees, plants and animals were created, they were asked to stay awake to fast and pray for seven nights to honor the Creator. The first night they all stayed awake, but the second night some fell asleep; the third night more dropped out, and so on.

By the seventh night, only a few were still awake. Of the animals, the owl (u-gu-gu), the panther (tsv-da-tsi), and a few others were still awake. These animals were given the power to see and go about in the dark and make prey of the birds and animals that must sleep at night.

Of the trees, only the cedar, the pine, the spruce, the holly, the hemlock, and the laurel were awake to the end. The Creator gave these trees the ability to keep their leaves and stay green all year round and gave them special power to be medicine for the Cherokee people.

Therefore, these trees are sacred and used for medicine by the Cherokee people to this day.”

Read more:

Biden Administration Highlights New Initiatives for Tribal Nations

U.S. President Joe Biden drew enthusiastic applause from tribal leaders attending day one of a two-day White House Tribal Nations Summit in Washington, where Biden announced new policies for improving tribal consultation across federal agencies.

“Consultation has to be a two-way, nation-to-nation exchange,” he said. “Federal agencies should strive to reach consensus among the tribes, and there should be adequate time for ample communication.”

Tribes have long sought more inclusion in federal decision-making on policies in keeping with the U.S. Constitution and hundreds of treaties negotiated with the U.S. government between 1778 and 1871.

In 2019, however, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found some federal agencies did not respect tribal sovereignty or tribes’ relationship with the government and failed to adequately consult tribes on infrastructure projects impacting tribal natural and cultural resources.

Biden announced he had signed a new memorandum of understanding (MOU), unifying consultation processes across the government agencies. It directs agency heads to keep public records on all consultations, summarizing all tribal concerns and recommendations and showing how tribal input is considered into the agency decisions.

Agency heads also must explain their reasoning if and when tribal suggestions are not incorporated into agency action.

“Tribal nations should know how their contributions influence the decision making,” Biden said, adding that the MOU will require all relevant federal agencies to participate in annual training on the tribal consultation process.

Managing environmental issues

Separately, U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland announced several initiatives aimed at strengthening Washington’s relationship with 574 federally recognized tribes and boosting their sovereignty and economic development.

From wildfires and drought to the widespread loss of species and their habitats, climate change is “the challenge of our lifetime,” Haaland told tribal leaders attending the first in-person summit.

“If we are going to successfully overcome these threats, we must work together," Haaland said.

To that end, the Commerce Department will join the Interior and Agriculture Departments by signing Joint Secretarial Order 3403. That order, issued in November 2021, is designed to ensure that federal agencies work with tribes to manage millions of hectares of federal lands, waters and wildlife.

“Today, the Departments of Interior and Agriculture are outlining a series of new steps to ensure tribes can participate in the stewardship of federal lands and waters,” Haaland said.

That includes, said Haaland, "producing a first of its kind report on the many existing legal authorities we have as agencies to advance co-stewardship with tribal nations as the United States works to honor our trust and treaty responsibilities to protect tribal sovereignty and revitalize tribal communities.”

Closing digital divide

A 2021 study by Arizona State University’s American Indian Policy Institute found that 18% of tribal reservation residents had no internet access and 33% were forced to rely on smartphones to access the internet.

Haaland announced that the Interior and Commerce departments will sign a memorandum of understanding with the Federal Communications Commission to better coordinate in promoting wireless services on tribal lands and give tribes a voice in developing national broadband policy.

The Interior Department also will establish a new Office of Indigenous Communication and Technology to help tribal nations and communities manage, develop and maintain broadband infrastructure, as well as forge partnerships with the tech industry.

“All of these new tools will help strengthen our nation-to-nation relationship while ensuring that communities have the tools — both new and old — to reach true self-determination and move toward a more prosperous era for Indian country,” Haaland said.

Documenting boarding school histories

Haaland also announced the Interior Department, with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, will in 2023 begin work on a permanent oral history project to document the experiences of students in the federal Indian boarding school system.

Following the discovery in 2021 of more than 200 sets of remains on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in Canada, the Interior Department launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to study the impact of these boarding schools on Native American attendees, descendants and their families.

The department released the first volume of findings in May, reporting that between 1819 and 1969, the federal government operated 408 federal schools in 37 states.

Investigators have so far identified more than 1,000 other federal and non-federal institutions involved in educating and assimilating Native American, Native Alaskan and Native Hawaiian children. These included day schools, orphanages and standalone dormitories.

They report that the schools used “systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies” in their effort to Americanize Native children, giving them English names, banning their languages, cultural and spiritual practices.

“The federal Indian Boarding School Initiative is about more than reliving the trauma of our past," Haaland said in her announcement Wednesday. “It's about making sure that survivors of these brutal federal policies are seen and heard and that their stories are told to future generations.”

- By Matt Dibble

Native American Tribe Helps Sacred Condors Recover After a Century’s Absence

California condors are North America’s largest bird. But they came close to extinction before conservationists and Indigenous communities joined to save them. Matt Dibble reports from California on how the Yurok Tribe is helping condors recover.

Native American News Roundup Nov. 13-19, 2022

Here is a summary of some of the top Native American-related news stories in the U.S. this week:

Lawmakers Consider Seating Cherokee Nation Delegate in US House

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. is urging Congress to honor a bargain made nearly 200 years ago to seat a Cherokee delegate in the U.S. House of Representatives.

The 1835 Treaty of New Echota set terms for the tribe's removal from Georgia to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma and included a Cherokee delegate to Congress.

"The carefully constructed promise...was in fact critical to secure the agreement of the Cherokee People," Hoskin told the House Rules Committee Wednesday, reminding them the treaty led to the deaths of thousands of Cherokees along the 1,000-mile Trail of Tears.

"The Treaty of New Echota is a living, valid treaty, and the delegate provision is intact," he said. "Lapse of time cannot abrogate a treaty."

The Cherokee Nation has selected former President Barack Obama adviser Kimberly Teehee to fill the seat. If confirmed, Teehee would join six nonvoting delegates representing the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the United States Virgin Islands.

"This can and should be done as quickly as possible," Committee Chairman James McGovern said. Lawmakers may first examine whether the treaty applies to other federally recognized Cherokee tribes in Oklahoma and North Carolina.

Read more:

FBI Head to Congress: Oklahoma Caseload Is Draining Agency Resources

FBI Director Christopher Wray says his agency's caseloads in Oklahoma increased dramatically following a U.S. Supreme Court decision giving federal and tribal governments, not the state, authority to prosecute violent crimes by or against Native Americans in more than 40% of Oklahoma.

The 2020 decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma blocked state government prosecutorial authorities in areas of eastern Oklahoma because, the court ruled, Congress never disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation there.

"In response the FBI surged national resources to ensure it was able to address its mission requirements to investigate major crimes in the newly designated Tribal Territory," Wray told members of the House Committee on Homeland Security Tuesday. "These surges subsequently caused resource strains on other investigative programs and threats."

In June 2022, Supreme Court justices reversed McGirt, ruling in Castro v. Huerta that "the Federal Government and the State have concurrent jurisdiction to prosecute crimes committed by non-Indians against Indians in Indian country."

That decision has taken some of the pressure off the FBI, Wray said, and could reduce agency caseloads in Oklahoma by up to 20%.

"This would free FBI resources to return to other national threat issues, while still providing Tribal communities with the FBI law enforcement services they've historically relied on," he said.

Tribes regard the Castro-Huerta decision as an attack on their sovereignty.

Harvard Museum to Return Native American Hair Samples

Harvard University has apologized for holding and is pledging to return to tribes and families hundreds of hair samples taken from Native American children in the federal boarding school system.

In 1930, physical anthropologist and Colorado State Museum curator George Woodbury launched a study of the structure of Native American hair to determine Native Americans' racial origins.

He collected hair samples from hundreds of Native American children in federal boarding schools, comparing them to hair samples from indigenous individuals in Canada, Asia, Central America, South America and Oceania, as well as mummified remains found in Colorado. And he took them with him when he became a lecturer at Harvard in 1935.

"We recognize that for many Native American communities, hair holds cultural and spiritual significance, and the Museum is fully committed to the return of hair back to families and tribal communities," Jane Pickering, director of Harvard's Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, said November 10.

Read more:

California to Honor Indigenous Northern California Tribes

State and tribal officials in California have broken ground on a monument honoring the Miwok and Nisenan peoples of Northern California. It will replace a statue of the controversial Spanish Catholic missionary Junipero Serra, which protestors toppled in July 2020 at the height of protests following the killing of George Floyd.

Serra was an 18th century Spanish missionary who founded a string of Roman Catholic missions in California to convert Indigenous peoples. In 2015, the Vatican canonized him as a saint. But for many Native Americans, Serra is a symbol of colonial oppression.

Serra's statue in the state capital Sacramento will be replaced with a bronze statue of the late William "Bill" Franklin, a well-known Miwok tribe member whom Assemblyman James C. Ramos called a "fierce protector and preservationist" of cultural dances and other ceremonies.

Read more:

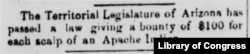

Feds Seize Purported Native American Scalp from New England Auction Dealer

The FBI is investigating whether an artifact up for sale by a Maine auction house is as advertsed: a Native American scalp.

Acting on a tip, investigators got a search warrant and seized from Poulin's Antiques and Auctions an item labeled as a "Mescallaro [sic] Apache scalp."

The 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act criminalizes the purchase, sale or transport of Native American remains.

"There is a process underway to determine whether the item is human, whether it is Native American, and whether, if Native American, the remains are that of a person who was a member of a particular tribe," Supervisory Assistant U.S. Attorney Joel Casey said.

No charges have been filed against the auction house, he added.

Read more:

California Tribes Hail Dam Removal Plan After 20-Year Fight

The largest dam removal in US history has received final federal approval in a major victory for environmentalists and Native American communities. The four dams along the border of California and Oregon have been blamed for the decline of salmon and other species. VOA reporter Matt Dibble filed this story:

US House Eyes Prospect of Seating Cherokee Nation Delegate

The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma moved a step closer on Wednesday to having a promise fulfilled from nearly 200 years ago that a delegate from the tribe be seated in the United States Congress.

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. was among those who testified before the U.S. House Rules Committee, which is the first to examine the prospect of seating a Cherokee delegate in the U.S. House of Representatives. Hoskin, the elected leader of the 440,000-member tribe, put the effort in motion in 2019 when he nominated Kimberly Teehee, a former adviser to President Barack Obama, to the position. The tribe's governing council then unanimously approved her.

Right goes back to 1835

The tribe's right to a delegate is detailed in the Treaty of New Echota signed in 1835, which provided the legal basis for the forced removal of the Cherokee Nation from its ancestral homelands east of the Mississippi River and led to the Trail of Tears, but it has never been exercised. A separate treaty in 1866 affirmed this right, Hoskin said.

"The Cherokee Nation has in fact adhered to our obligations under these treaties. I'm here to ask the United States to do the same," Hoskin said to the panel.

Hoskin suggested to the committee that Teehee could be seated as early as this year by way of either a resolution or change in statute, and the committee's chairman, Massachusetts Democratic Rep. James McGovern, and other members supported the idea that it could be accomplished quickly.

"This can and should be done as quickly as possible," McGovern said. "The history of this country is a history of broken promise after broken promise to Native American communities. This cannot be another broken promise."

'We should be treated as siblings'

But McGovern and other committee members, including ranking member Republican Rep. Tom Cole of Oklahoma, a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation, acknowledged there are some questions that need to be resolved, including whether other Native American tribes are afforded similar rights and whether the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma is the proper successor to the tribe that entered into the treaty with the U.S. government.

McGovern said he has been contacted by officials with the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and the Delaware Nation, both of which have separate treaties with the U.S. government that call for some form of representation in Congress. McGovern also noted there are two other federally recognized bands of Cherokee Indians that argue they should be considered successors to the 1835 treaty: the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians based in North Carolina, both of which reached out to his office.

The UKB selected its own congressional delegate, Oklahoma attorney Victoria Holland, in 2021. Holland said in an interview with The Associated Press that her tribe is a successor to the Cherokee Nation that signed the 1835 treaty, just like the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma.

"As such, we have equal rights under all the treaties with the Cherokee people and we should be treated as siblings," Holland said.

Only a few Native Americans serve in Congress, including Cole and Republican Rep. Markwayne Mullin, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation who was elected this month to represent Oklahoma in the U.S. Senate, where he will become the first Native American in that body in nearly 20 years.

"As a member of the Cherokee Nation, I firmly believe the federal government must honor its trust and treaty responsibilities to Indian Nations," Mullin said in a statement. "We are only as good as our word."

Members of the committee seemed to be in agreement that any delegate from the Cherokee Nation would be similar to five other delegates from the District of Columbia, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa and the Virgin Islands. These delegates are assigned to committees and can submit amendments to bills but cannot vote on the floor for final passage of bills. Puerto Rico is represented by a nonvoting resident commissioner who is elected every four years.

Native American News Roundup Nov. 6-12, 2022

Here is a summary of some of the top Native American-related stories in U.S. news this week:

Some Wins, Some Losses for Indigenous Candidates in Midterm Vote

More than 90 Indigenous candidates ran in Tuesday’s U.S. midterm elections, with 11 congressional candidates.

Republican Markwayne Mullin, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, will represent Oklahoma in the U.S. Senate, the first Native American in the Senate since former Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell, a Republican from Colorado, retired in 2005.

Representative Sharice Davids, a Kansas Democrat, won a third term in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Republican U.S. Rep. Tom Cole of the Chickasaw Nation will serve an 11th term in Oklahoma’s fourth congressional district.

Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Cherokee citizen, won the governor’s race in Oklahoma.

Democrat Lynnette Grey Bull of the Northern Arapaho and Standing Rock Sioux tribes lost to Republican Harriet Hageman in the contest for Wyoming’s seat in the U.S. House.

Native News Online is keeping track of the candidates; read more here.

California Tribes Retain Exclusive Gambling Rights

California voters overwhelmingly shot down two measures that would have legalized sports gambling.

Proposition 26 would have legalized sports betting at tribal casinos and allowed them to offer dice games and roulette. Proposition 27 would have authorized online and mobile sports betting.

Tribes supported Proposition 26, which would have expanded their gaming operations, but opposed Proposition 27, as it would have allowed online sports betting outside of Native American lands and diminished their gaming exclusivity.

Today, 76 California Indian gaming casinos are owned by 73 of the state's 109 Tribes, making California the nation's largest Indian gaming state with annual total revenues of nearly $9 billion.

Read more here.

After Two-decade Wait, Sacred Lakota Artifacts Are Home

A delegation of Oglala and Cheyenne River Lakota, and Wounded Knee Survivors Association members traveled to Barre, Massachusetts, to take back more than 130 artifacts from a museum that has held them for more than a century.

During a public ceremony at a local school, descendants spoke of their ancestors killed or wounded in the 1890 massacre that took the lives of hundreds of followers of Miniconjou Lakota leader Spotted Elk as they traveled to the Pine Ridge Reservation.

In 1992, a local anthropologist alerted the Wounded Knee Survivors Association about the artifacts held in the Barre Museum.

“I was shocked,” said Alex White Plume, a former Oglala president who was among a group of Lakota who traveled to Barre to see the items and appeal for their return.

“We went into the museum, and you could just sense the spirits,” he told VOA. “I saw baby clothes, totally beaded in just beautiful designs. And then I’d look on the back and there would be a big black hole where the bullet went through.”

If these things remained in the museum, White Plume said, their spirits would remain “captive on this earth.”

Once back at Pine Ridge, the artifacts will be stored at the Oglala Lakota College until the 130th anniversary of the massacre this December 29, when they will be honored in a ceremony and distributed between tribes.

Read more here.

Tribes Hopeful Indian Child Welfare Law Will Hold

This week, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in a case that could decide not only the future of many Native American children but ultimately impact the sovereignty of Native American nations.

Brackeen v. Haaland began as a lawsuit challenging the Indian Child Welfare Act, a 1978 law passed to stop states from placing Native American children in non-Native American families, a practice many Native Americans believe to be a continuation of historic efforts at forced assimilation.

The suit was first brought in 2016 by three sets of prospective adoptive parents, each non-Native American and fostering Native American children. They were joined by the states of Texas, Indiana and Louisiana with backing from the conservative Goldwater Institute in taking the U.S. government to court to try to overturn the ICWA.

Now before the nation’s highest court, the suit argues that states should decide child welfare cases, not the federal government. Supporters say the law discriminates against non-Native families based on race, in violation of the Constitution’s equal protection clause.

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress, not states, plenary authority to deal with issues concerning Indian tribes.

“Here’s the truth,” Cherokee Nation Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr., said in a statement about the suit. “The U.S. Constitution recognizes tribes as sovereign nations, and courts have repeatedly recognized that tribal citizenship is a political classification. That may be an inconvenient fact for those who want to convince the court that ICWA violates the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, but neither the facts nor precedent are on their side.”

Tribes worry that if ICWA is modified or overturned, it could pave the way for constitutional challenges to other federal laws and policies impacting tribes, such criminal jurisdiction, casino gaming and tribal mineral rights. The court’s decision is expected next June.

Legal analyst and Supreme Court watcher Amy L. Howe notes that Court appeared divided.

"After more than three hours of oral argument, several justices expressed doubt about specific provisions of the wide-ranging law, even if they did not appear inclined to strike down the law in its entirety," she wrote. "Wednesday’s argument suggested a result that, although not what the federal government and the tribes might want, also might not be the catastrophic result that they have feared."

Read more here:

Justices Seem to Favor Most of Native Child Welfare Law

The U.S. Supreme Court appeared likely Wednesday to leave in place most of a federal law that gives preference to Native American families in foster care and adoption proceedings of Native children.

The justices heard more than three hours of arguments in a broad challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act, enacted in 1978 to address concerns that Native children were being separated from their families and, too frequently, placed in non-Native homes.

It has long been championed by tribal leaders as a means of preserving their families, traditions and cultures. But white families seeking to adopt Native children are among the challengers who say the law is impermissibly based on race and prevents states from considering those children's best interests.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh called the case difficult because the court is being called on to draw a line between tribal sovereignty and "the fundamental principle that we don't treat people differently because of race, ethnicity or ancestry."

He was among the conservative justices who expressed concern about at least one aspect of the law that gives preference to Native parents, even if they are of a different tribe than the child they are seeking to adopt or foster. Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Samuel Alito and Justice Amy Coney Barrett also raised questions about whether that provision looked more like a racial classification that the court might frown upon.

"To get to the heart of my concern about this, Congress couldn't give a preference for white families to adopt white children, Black families to adopt Black children, Latino families to adopt Latino children, Asian families to adopt Asian children," Kavanaugh said.

But none of the non-Native families involved in the case has been affected by the preference the conservative justices objected to, Justice Department lawyer Edwin Kneedler told the court.

Even if there is a court majority to strike down that provision, the rest of the law could be kept in place, said Ian Gershengorn, a lawyer for the Cherokee Nation, the Navajo Nation and other tribes.

He urged the court to uphold the law "that has made such a meaningful difference to so many children."

Representing the non-Native families, lawyer Matthew McGill called on the court to strike down the law because it "flouts the promise of equal justice under law."

Justice Neil Gorsuch, a conservative who is a strong supporter of Native Americans' rights, and the court's three liberal justices seemed strongly inclined to uphold the law in its entirety.

"Congress understood these children's placement decisions as integral to the continued thriving of Indian communities," said liberal Justice Elena Kagan.

Gorsuch said a broad ruling in favor of the challengers also would take "a huge bite out of" other federal programs that benefit Native Americans, including health care.

Most tribes ask court to uphold law

The law's fate is in the hands of a court that has made race a focus of its current term, in cases involving the redrawing of congressional districts and affirmative action in college admissions. Two members of the court, Roberts and Barrett, also are the parents of adopted children.

The full 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals struck down parts of the law last year, including preferences for placing Native children with Native adoptive families and in Native foster homes. It also said Congress overstepped its authority by imposing its will on state officials in adoption matters.

But the 5th Circuit also ruled that the law generally is based on the political relationship between the tribes and the U.S. government, not race.

The tribes and the Biden administration appealed some parts of the lower court ruling, while the white families and Texas, allied with those families, appealed others.

More than three-quarters of the 574 federally recognized tribes in the country have asked the high court to uphold the law in full, along with tribal organizations. They fear widespread impacts if the court attempts to dismantle the tribes' status as political sovereigns.

Support from state attorneys general

Nearly two dozen state attorneys general across the political spectrum filed a brief in support of the law. Some of those states have codified the federal law into their own state laws.

A ruling in favor of the families and Texas could undercut the 1978 law and, the tribes fear, have broader effects on their ability to govern themselves.

When child protection authorities remove Native children from their homes, the law requires states to notify tribes and seek placement with the child's extended family, members of the child's tribe, or other Native American families.

All of the children who have been involved in the current case at one point are enrolled or could be enrolled as Navajo, Cherokee, White Earth Band of Ojibwe and Ysleta del Sur Pueblo. Some of the adoptions have been finalized while some are still being challenged.

Before the Indian Child Welfare Act was enacted, between 25% and 35% of Native American children were being taken from their homes and placed with adoptive families, in foster care or in institutions. Most were placed with white families or in boarding schools in attempts to assimilate them.

Native American News Roundup Oct. 30 – Nov. 5, 2022

Here is a summary of some of the top Native American-related headlines around the U.S. this week:

November Proclaimed Native American Heritage Month

U.S. President Joe Biden Monday declared November a time to “celebrate Indigenous peoples past and present and rededicate ourselves to honoring Tribal sovereignty, promoting Tribal self-determination, and upholding the United States’ solemn trust and treaty responsibilities to Tribal Nations.”

“America has not always delivered on its promise of equal dignity and respect for Native Americans,” the President wrote. “For centuries, broken treaties, dispossession of ancestral lands, and policies of assimilation and termination sought to decimate Native populations and their ways of life.”

Even so, he noted that Indigenous Americans, their governments and communities have prevailed and flourished.

“As we look ahead, my Administration will continue to write a new and better chapter in the story of our Nation-to-Nation relationships,” he pledged.

Read more:

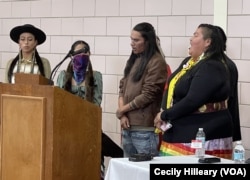

Kansas Schools Face Pressure to Drop Native American Mascots

The state of Kansas is home to four federally recognized tribes: the Iowa Tribe, the Kickapoo Tribe, the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation and the Sac and Fox Nation.

The state is also home to almost thirty school districts with sports teams using Native American-themed names like Braves, Warriors, Redmen and the racial slur, R—skins.

In October, the recently formed Kansas Advisory Council for Indigenous Education, which includes representatives from all four tribes, called on the Kansas State Board of Education to press schools to abandon the mascots, a matter that could be decided when the board meets again on November 9. See video below to hear their recommendations and reactions from educators.

The board lacks authority to force school districts to change their mascots. That would be up to the local boards of education.

And, as Kansas Public Radio noted, their recommendation may not be enough to “overcome decades of tradition and identity invested in mascots that communities often see as honoring American Indians rather than symbols of racist stereotyping.”

Read more:

New Mexico Pueblo Turns to Tradition in Face of Climate Threats

Fortune Magazine this week reports that Pueblo citizens are turning to tradition to fight the effects of the worst megadrought in more than 1,000 years.

For three hundred years, the Tewa people of what is today the Santa Clara Pueblo lived in cliff dwellings near Española, New Mexico, until drought conditions drove them ten miles east to the banks of the Rio Grande.

Today, the Santa Clara Pueblo is once again under threat: it has suffered three large wildfires in just over a dozen years. The worst was the June 2011 Las Conchas fire that burned more than 6,710 hectares—about half of the entire reservation. When rain finally came—just a quarter inch—it set off devastating flash floods that drained ponds and unleashed boulders, trees and sediment.

They are now engaged in a race against time and climate change, using both modern science and traditional farming and burning techniques to restore their land, forests and waterways.

Read more:

Google’s New Logo Features ‘Little Brother to War’

Google users this week may have noticed that its latest logo celebrates Indigenous North American stickball, one of America’s oldest team sports.

Marlena Myles, a Spirit Lake Dakota/Mohegan/Muscogee artist and illustrator based in St. Paul, Minnesota, designed the logo, and explained to Google what stickball, represents to Native communities.

“It’s a healing sport for the whole community, people aren’t just playing to win, but are playing for their community’s health. This sport has played an active role through the generations in our many Tribes, and it will continue to do so,” she said.

As VOA has previously reported, stickball is sometimes called “the little brother to war,” as it was historically seen as a healthier alternative to solving conflicts by going to war.

The rules of the game are simple: Team members use long wooden sticks with woven cups at one end to scoop up and drive a small ball toward goals at either end of the playing field. Players do not wear any protective gear or shoes and they are not allowed to use their hands.

To learn more about stickball, watch video below:

Native American Fashion Showcased

Denver Arts and Venues recently hosted a fashion show featuring Native American designers with historic ties to Colorado and nearby states. Kelly Holmes, the Cheyenne River Lakota founder of Native Max Magazine, curated and produced the runway event. VOA reporter Scott Stearns was there and filed this video report:

Native American Fashions Strut Denver Runway

The international market for Native American fashion is growing. VOA correspondent Scott Stearns caught up with Indigenous designers at a Native American fashion show in the Western U.S. state of Colorado. Videographer: Scott Stearns, Jodi Westrum