Native Americans

Native American News Roundup March 5-11, 2023

Here are some of the Native American-related stories making headlines this week:

California academic may have used Native American remains as teaching tools

ProPublica reports that retired University of California Berkeley Professor Tim White routinely used “a vast collection of human remains” to teach anthropology and osteology.

According to investigators, White supervised “a vast collection of human remains — bones sorted by body part and stored in wooden bins” after he joined the faculty in 1977.

ProPublica has found that the vast majority of remains in UC-Berkeley’s collection came from ancestral sites in California.

Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in 1990, calling on federally funded institutions to report and repatriate human remains and funerary artifacts.

White, now retired, advised the university’s repatriation decisions and argued that because there was no way to identify the origin of the bones, NAGPRA did not apply.

ProPublica and NBC earlier this year launched an investigation into why the remains of 110,000 Native American, Native Hawaiian and Alaska Native ancestors are still held by museums, universities and federal agencies more than two decades after NAGPRA was passed. They report that UC-Berkeley holds the largest collection of unrepatriated Native American remains in the US.

Read more:

Harvard official says university poised to speed up repatriation of remains

In a related story, Native News Online spoke with Kelli Mosteller, a citizen of the Potawatomi Nation in Oklahoma who directs Harvard University’s Native American Program.

ProPublica found that Harvard University still holds the remains of at least 6,165 Native American ancestors, the fourth largest collection in the U.S.

Mosteller said Harvard had previously lacked the staff to manage repatriation but has now doubled its staff to help with NAGPRA compliance.

“I know Harvard has a terrible history, and they know they have a terrible legacy. But I have faith that we're moving in the right direction, because I'm on the ground watching us do the work every day, trying to right that history,” Mosteller said.

Harvard in November apologized for holding and pledged to return hundreds of hair samples taken from Native American children in the federal boarding school system. https://www.voanews.com/a/native-american-news-roundup-november-13-19-2022-/6839172.html

Read more:

Patrice Kunesh to lead HHS Native American Program

The U.S. Senate Wednesday confirmed Patrice H. Kunesh as commissioner of the Health and Human Service Department’s Administration for Native Americans (ANA).

Kunesh, who is of Standing Rock Lakota descent, is a nationally recognized attorney and policy advocate. She was nominated by President Joe Biden nine months ago.

“I am deeply honored to be confirmed for this opportunity to serve Native peoples in this role,” said Kunesh. “I am so inspired by this administration’s abiding respect for Native governance and cultural integrity.

The ANA was established in 1974 to promote self-sufficiency for Native Americans, Alaska Natives and Hawaiian Native tribes and to reduce dependency on public funds and social services. It also works to improve access to services and programs safeguarding the health and well-being of Native children and families, and boost youth and intergenerational activities in tribal communities.

See how lawmakers voted here:

Native American journalist and educator defends controversial tweet

Oglala Lakota Chicano journalist and University of Denver lecturer Simon Moya-Smith drew anger on Twitter and at least two media outlets this week after suggesting that prisons and laws banning homosexuality and abortion were exports from Europe.

“Simon Moya-Smith, a left-wing Native-American writer, envisions a primordial progressive utopia in North America — before the arrival of the colonists, Indian tribes held hands, sang kumbaya, passed the Green New Deal, doled out abortions and sex-change surgeries like candy,” an editorial in the conservative National Review reads. It references a folk song/religious spiritual adopted as an expression of racial unity during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

The Review noted that the Navajo Nation banned abortion in 2005 and stated that only a handful of tribes have legalized same-sex marriage.

As of mid-week, Moya-Smith’s tweet had earned more than 7 million views and thousands of comments, many of them derogatory.

“Yea they just scalped people and burned them alive,” read one response. Others posted graphics depicting human sacrifice among the Aztecs.

“As soon as you say anything about no prisons or no abortion, they're going to bring up the Navajo and the Aztecs, lumping us all into the same category,” Moya-Smith told VOA. “They like to push the narrative that when white Christians came here, they built this country, and it worked out well for everyone. But not for Indigenous people. And that’s my point.”

And he added, “I feel like I have to put out tweets like this every now and then so people can understand how much racism is really out there.”

Native American News Roundup February 26 to March 4, 2023

Here is a summary of some of the top Native American-related news making headlines this week:

Remembering the Wounded Knee takeover

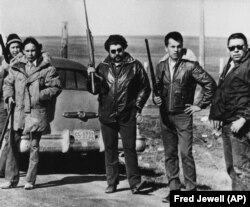

It was 50 years ago this week that Oglala Lakota activists and members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) besieged the town of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, the site of an Army massacre of Lakota 80 years earlier.

AIM was a grassroots civil rights movement organized in Minneapolis in the late 1960s which evolved into a movement to empower Native pride, economic empowerment, and the assertion of tribal treaty rights.

High-profile protests by AIM included the occupation of Alcatraz Island from 1969 to 1971 and a partial take-over of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in late 1972.

Oglala Lakota at the time were divided between “progressive” supporters of tribal chairman Dick Wilson and “traditionalists,” who accused him of corruption, favoritism and being too friendly with Washington.

Tensions worsened after Wilson created a private militia accused of using violence against his opponents. There was also the kidnap and murder of an Oglala man by a group of four men and one woman, all white, in nearby Gordon, Nebraska, which attracted the interest and involvement of AIM.

After failing to have Wilson impeached, more than 200 AIM members and Oglala supporters descended on Wounded Knee February 27, 1973, triggering a 71-day standoff that involved the FBI, the U.S. Marshal Service and the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. The conflict left two dead and a U.S. Marshal paralyzed from a gunshot wound.

On May 6, the government and AIM reached an accord: the occupiers would surrender and turn over their weapons; the Justice Department would investigate Wilson and militia abuses; and a White House delegation would hold talks with Lakota leaders to re-examine treaty obligations.

The case drew global media attention, despite FBI efforts to block reporters, and helped raise awareness about Native American rights. Today, Pine Ridge remains among the poorest communities in the United States.

Read more:

HUD announces affordable housing grants

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) announced Tuesday more than $794 million in Indian Housing Block Grants to help nearly 600 Native American tribes, Alaska Native villages and other Native entities create affordable housing in tribal communities.

"HUD is committed to supporting our Tribal communities by providing resources that will help persons living in those neighborhoods thrive," HUD Secretary Marcia L. Fudge said in a press release. "We know that these grants will not only be used to create affordable housing, but they will also provide much needed wrap-around services and solutions to complex issues."

In 2017, HUD released the results of a congressionally mandated study of the housing needs in tribal areas. It found overcrowding combined with deficiencies in plumbing, heating, electrical and other maintenance issues in 34% of tribal households compared with 7% of all U.S. households.

Read more:

U. Minn to return land to Chippewa Band

The University of Minnesota says it will return some 1,400 hectares (3,391 acres) of land to the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, in recognition that the lands were promised to the band by treaty.

The land, which currently houses the university’s Cloquet Forestry Center, has been under the university’s control since 1909, and in today’s market is worth about $35 million.

In her proposal to UM’s board of regents, university President Joan Gabel characterized the land transfer as a “repatriation of land to its original caretakers” and a “positive step in repairing and strengthening the University’s relationship with the Fond du Lac Band and Indigenous communities throughout the state.”

Gabel cautioned the board that “there are considerable steps ahead to address a variety of complicated issues such as ownership of the land, public engagement and consultation, the continuation of research, and a variety of questions that come up for something this complicated.”

See her statement to the board below:

South Dakota lawmakers greenlight study on Indian child welfare

A South Dakota House panel this week approved a 17-member, two-year task force to study Native American overrepresentation in South Dakota’s foster care system.

Historically, the federal government removed Native children from their families and tribes and placed them in boarding schools. Welfare agencies later placed them in white foster and adoptive families. Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978 to end these removals.

But studies show that more than half of South Dakota’s foster children are Native American, even though Native children make up only 12% of the population. Members of the nine tribes in the state see this as a continuation of historic policies of forced assimilation.

Senate Bill 191 cleared the full state Senate last week. Its sponsor, Sen. Red Dawn Foster (D-Pine Ridge), said the task force will consult with all stakeholders, including lawmakers, the state foster care system, and representatives from the state’s nine tribes.

Phony 'Sober Living' Homes in Arizona Target Vulnerable Native Americans

On a hot day in July 2022, a gray SUV pulled into the parking lot of a grocery store in the Navajo community of Shiprock, New Mexico. One of the three men talking outside the store was Marvin, a 47-year-old Navajo man from Utah.

“The driver and another guy asked us if we needed a place to stay,” Marvin told VOA, asking that his full name not be used. “They told us they ran a sober home. They said there was plenty of food in the refrigerator.”

Hours later, Marvin says he and his companions were locked inside a house 600 kilometers away in Phoenix, Arizona, victims of a growing scam that fuels addictions to defraud health care funds.

Sober homes are affordable alcohol and drug-free group homes designed to help recovering addicts transition from hospital rehabilitation programs to independent living in their communities. Thousands of licensed sober homes operate across the U.S., and studies have shown that they can help delay or prevent recovering addicts from relapsing.

Scam sober homes in Phoenix use Native Americans to enroll for healthcare benefits under the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, which partners with the federal Indian Health Service to pay for behavioral health services for members of federally recognized tribes. Fraudsters bill for benefits never delivered to at-risk Native Americans.

“They don’t get any treatment and are given drugs or alcohol to keep them dependent so they can stay in these so-called ‘programs’ longer,” said the organizer of a Phoenix neighborhood watch group who spoke with VOA and asked not to be identified for fear of retribution by gangs running the fraud.

Special Agent Antoinette Ferrari investigates financial crimes for the FBI’s Phoenix field office. She told VOA that hundreds of fraudulent sober homes have popped up across Phoenix in the past year alone.

“Medicaid and health care plans are a huge, multi-billion-dollar industry, and these fraudsters are costing taxpayers millions of dollars,” said Ferrari.

The FBI is asking victims to come forward, but agents stress that their investigation, for now, is focused on the fraudulent use of federal funds, not human trafficking or kidnapping.

A Phoenix, Arizona, resident provided VOA this video doorbell footage which shows a young man returning to a sober living home whose operators force him to sleep outside at night. Fraudsters bill the state Medicaid for services never delivered to at-risk Native Americans.

Law enforcement and community leaders say scam sober homes are skirting Phoenix regulations that facilities with six or more residents must register with the city and may not operate within 1,320 feet of any other group home. By keeping just five people to a house, they avoid registration and can rent adjoining properties.

“If the rule is no more than five residents, one operator could open up four group homes on the same street and get away with it,” said the neighborhood watch leader. “Nobody's regulating them. They're just popping up like cockroaches.”

Reva Stewart, Navajo, manages a Native American arts, crafts and music store across the street from Phoenix’s Indian Medical Center.

“Last summer, I started seeing these vans pulling up and taking Navajo relatives away,” she said. “Something didn’t seem right about it, so I started documenting it.”

Last October, she posted a video of a recruiter in action on Facebook. “And that's when people started reaching out to me from all over Phoenix,” she said. “I had no idea the problem was this big.”

So Stewart teamed up with family services case worker Colleen Chatter, Navajo, to organize Advocates for Native Relatives to identify fraudulent group homes and help victims get back home.

Snacks, drinks and a bus ticket

In December, word of their work reached Marvin, who says scammers supplied him with drugs and alcohol to keep him rotating through six homes in five months. The first time he ran away, he says operators found him and threatened him into returning.

Last week, Marvin escaped through a back door, hopped a fence, and walked more than 40 kilometers through the night to Stewart’s store. She gave him snacks, drinks and a bus ticket to his mother’s home in Colorado, all from her own pocket.

“I’m tired,” he told VOA via Facebook video, shivering in the morning chill. "I really want to go back (home). This is just not me over here in Phoenix. Probably everybody's wondering where I'm at again. I haven't even been able to call home."

Legislative moves

Neither the Phoenix Police Department, Navajo Nation police nor the office of the Arizona Attorney General responded to VOA’s requests for comment on fraudulent sober homes.

Arizona lawmakers have introduced several bills aimed at tightening regulations on group homes, including written discharge and transfer plans and quarterly updates on compliance with fire and zoning restrictions.

Legacy of Wounded Knee Occupation Lives On 50 Years Later

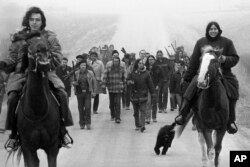

Madonna Thunder Hawk remembers the firefights.

As a medic during the occupation of Wounded Knee in early 1973, Thunder Hawk was stationed nightly in a frontline bunker in the combat zone between Native American activists and U.S. government agents in South Dakota.

“I would crawl out there every night, and we’d just be out there in case anybody got hit,” said Thunder Hawk, of the Oohenumpa band of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, one of four women assigned to the bunkers.

Memories of the Wounded Knee occupation — one in a string of protests from 1969 to 1973 that pushed the American Indian Movement to the forefront of Native activism — still run deep within people like Thunder Hawk who were there.

Thunder Hawk, now 83, is careful about what she says today about AIM and the occupation, but she can’t forget that tribal elders in 1973 had been raised by grandparents who still remembered the 1890 slaughter of hundreds of Lakota people at Wounded Knee by U.S. soldiers.

“That’s how close we are to our history,” she told ICT recently. “So anything that goes on, anything we do, even today with the land-back issue, all of that is just a continuation. It’s nothing new.”

Other feelings linger, too, over the tensions that emerged in Lakota communities after Wounded Knee and the virtual destruction of the small community. Many still don’t want to talk about it.

But the legacy of activism lives on among those who have followed in their footsteps, including the new generations of Native people who turned out at Standing Rock beginning in 2016 for the pipeline protests.

“For me, it’s important to acknowledge the generation before us — to acknowledge their risk,” said Nick Tilsen, founder of NDN Collective and a leader in the Standing Rock protests, whose parents were AIM activists. “It’s important for us to honor them. It’s important for us to thank them.”

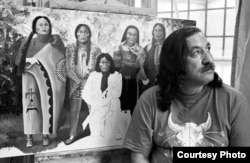

Akim D. Reinhardt, who wrote the book, “Ruling Pine Ridge: Oglala Lakota Politics from the IRA to Wounded Knee,” said the AIM protests had powerful social and cultural impacts.

“Collectively, they helped establish a sense of the permanence of Red Power in much the way that Black Power had for African Americans, a permanent legacy,” said Reinhardt, a history professor at Towson University in Towson, Maryland.

“It was the cultural legacy that racism isn’t OK and people don’t need to be quiet and accept it anymore," he said. "That it’s OK to be proud of who you are.”

A series of events in South Dakota in recent days recognized the 50th anniversary of the occupation, including powwows, a documentary film showing and a special honor for the women of Wounded Knee.

'Thunderbolt' of protest

The occupation began on the night of Feb. 27, 1973, when a group of warriors led by Oklahoma AIM leader Carter Camp, who was Ponca, moved into the small town of Wounded Knee. The group took over the trading post and established a base of operations along with AIM leaders Russell Means, of the Oglala Sioux Tribe; Dennis Banks, who was Ojibwe; and Clyde Bellecourt, of the White Earth Nation.

Within days, hundreds of activists had joined them for what became a 71-day standoff with the U.S. government and other law enforcement.

It was the fourth protest in as many years for AIM. The organization formed in the late 1960s and drew international attention with the occupation of Alcatraz in the San Francisco Bay from 1969-1971. In 1972, the Trail of Broken Treaties brought a cross-country caravan of hundreds of Indigenous activists to Washington, D.C., where they occupied the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters for six days.

Then, on Feb. 6, 1973, AIM members and others gathered at the courthouse in Custer County, South Dakota, to protest the killing of Wesley Bad Heart Bull, who was Oglala Lakota, and the lenient sentences given to some perpetrators of violence against Native Americans. When they were denied access into the courthouse, the protest turned violent, with the burning of the local chamber of commerce and other buildings.

Three weeks later, AIM leaders took over Wounded Knee.

“It had been waiting to happen for generations,” said Kevin McKiernan, who covered the Wounded Knee occupation as a journalist in his late 20s and who later directed the 2019 documentary film, “From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock.”

“If you look at it as a storm, the storm had been building through abuse, land theft, genocide, religious intoleration, for generations and generations,” he said. “The storm built up, and built up and built up. The American Indian Movement was simply the thunderbolt.”

The takeover at Wounded Knee grew out of a dispute with Oglala Sioux tribal leader Richard Wilson but also put a spotlight on demands that the U.S. government uphold its treaty obligations to the Lakota people.

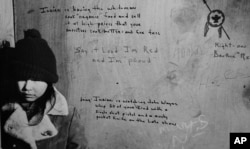

By March 8, the occupation leaders had declared the Wounded Knee territory to be the Independent Oglala Nation, granting citizenship papers to those who wanted them and demanding recognition as a sovereign nation.

The standoff was often violent, and supplies became scarce within the occupied territory as the U.S. government worked to cut off support for those behind the lines. Discussions were ongoing throughout much of the occupation, with several government officials working with AIM leaders to try and resolve the issues.

The siege finally ended on May 8 with an agreement to disarm and to further discuss the treaty obligations. By then, at least three people had been killed and more than a dozen wounded, according to reports.

Two Native men died. Frank Clearwater, identified as Cherokee and Apache, was shot on April 17, 1973, and died eight days later. Lawrence “Buddy” Lamont, who was Oglala Lakota, was shot and killed on April 26, 1973.

Another man, Black activist Ray Robinson, who had been working with the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization, went missing during the siege. The FBI confirmed in 2014 that he had died at Wounded Knee, but his body was never recovered. A U.S. marshal who was shot and paralyzed died many years later.

Camp was later convicted of abducting and beating four postal inspectors during the occupation and served three years in federal prison. Banks and Means were indicted on charges related to the events, but their cases were dismissed by a federal court for prosecutorial misconduct.

Today, the Wounded Knee National Historic Landmark identifies the site of the 1890 massacre, most of which is now under joint ownership of the Oglala Sioux and Cheyenne River Sioux tribes.

The tribes agreed in 2022 to purchase 40 acres that included the area where most of the carnage took place in 1890, the ravine where victims fled and the area where the trading post was located.

The purchase, from a descendant of the original owners of the trading post, included a covenant requiring the land to be preserved as a sacred site and memorial without commercial development.

And though internal tensions emerged in the AIM organization in the years after the Wounded Knee occupation, AIM continues to operate throughout the U.S. in tribal communities and urban areas.

In recent years, members participated in the Standing Rock protests and have persisted in pushing for the release from prison of former AIM leader Leonard Peltier, who was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder despite inconsistencies in the evidence in the deaths of two FBI agents during a shootout in 1975 on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

A new generation

Tilsen, now president and chief executive of NDN Collective, an Indigenous-led organization centered around building Indigenous power, traces the roots of his activism to Wounded Knee.

His parents, JoAnn Tall and Mark Tilsen, met at Wounded Knee, and he praises the women of the movement who sustained the traditional matriarchal system during the occupation.

“I grew up in the American Indian Movement,” said Tilsen, a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation. “It wasn’t a question about what you were fighting for. You were raised up in it. In fact, if you didn’t fight, you weren’t going to live.”

Tilsen credits AIM and others for most of the rights Native Americans have today, including the ability to operate casinos and tribal colleges, enter into contracts with the federal government to oversee schools and other services, and religious freedom.

He said the movement showed the world that tribes were sovereign nations and their treaties were being violated. And when AIM and spiritual leaders such as Henry Crow Dog, Leonard Crow Dog and Matthew King joined the fight, it became intergenerational.

“It became a spiritual revolution,” he said. “It also became a fight that was about human rights. It became a fight that was about where Indigenous people aren’t just within the political system of America, but within the broader context of the system; of the world.”

Tilsen appreciates that his parents were willing to participate in an armed revolution to achieve one of their dreams of establishing KILI radio station, known as the “Voice of the Lakota Nation,” which began operating in 1983 as the first Indigenous-owned radio station in the United States.

The Dakota Access Pipeline protest in 2016 became a defining moment for him and his brother. They had wondered, he said, what would be their Wounded Knee?

“What made it so powerful and what made it different was that you actually had grassroots organizers and revolutionaries and official tribal governments coming together, too,” Tilsen said. “I think that Standing Rock in particular actually reached way further than Wounded Knee because of how the issue was framed around ‘water is life.’”

Alex Fire Thunder, deputy director of the Lakota Language Consortium, said the occupation of Wounded Knee and other activism helped revitalize Indigenous languages and cultures. His mother was too young to have participated in the occupation but he said she remembered visits from AIM members in the community.

“The whole point of AIM, the American Indian Movement, was to bring back a sense of pride in our culture,” Fire Thunder, Oglala Lakota, told ICT.

Future generations

For Thunder Hawk, the issues became her lifelong work rather than momentary activism.

She joined AIM in 1968 and participated in the occupation at Alcatraz, the BIA headquarters, the Custer County Courthouse and Wounded Knee, as well as the Standing Rock pipeline protest in 2016.

She said work being done today by a new generation is a continuation of the work her ancestors did.

“That’s why we were successful in Indian Country, because we were a movement of families,” she said. “It wasn’t just an age group, a bunch of young people carrying on.”

She hopes her legacy will live on, that her great-great-grandchildren will see not just a photo of her but know what she sounded like and the person she seemed to be.

It’s something that she can’t have when she looks at a photo of her paternal great-grandparents.

“Hopefully that’s what my descendants will see, you know?” she said. “And with the technology nowadays, they can press a button, maybe, and it’ll come up.”

Frank Star Comes Out, the current president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, also believes it’s time for the previous generation’s work to be recognized.

Some of his family members strongly supported AIM, including his mother and father. He said it's important to fight for his people, who survived genocide.

“That’s why I support AIM, not only on a family level,” he said. “I have a lot of pride in who I am as a Lakota. … Times (have) changed. Now I’m using my leadership to help our people rise, to give them a voice. And I believe that’s important for Indian Country.”

Native American News Roundup Feb. 19-25, 2023

Here is a summary of Native American-related stories making headlines this week:

Utah House to consider ICWA protections ahead of SCOTUS ruling

As the U.S. Supreme Court weighs whether to revoke all or parts of the Indian Child Welfare Act, lawmakers in Utah are working to make sure that Native American children in Utah’s welfare system won’t be removed from their tribes regardless of how justices rule.

House Bill 40, sponsored by Utah Representative Christine Watkins (Republican), is patterned after ICWA and specifies that Native families would be given preference in adoption and foster care cases involving children from the eight tribes in that state. Watkins said she wanted to make sure that federal language would be codified in Utah law before the current legislative session ends in early March — and well before SCOTUS is expected to release its decision in early summer.

Utah’s House Judiciary Committee placed the bill on hold in January, and after some tweaking, the bill will now go before the full House for consideration.

Read more:

Indigenous studies center to open near former Carlisle Indian School

Dickinson College, located near the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, has announced it will develop a new center and academic program dedicated to Native American and Indigenous Studies.

Supported by a $800,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation, the Center for the Futures of Native Peoples is looking to hire a director this spring. American studies professor Darren Lone Fight, a citizen of the Muscogee Nation and an enrolled member of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Sahnish Nation, will serve as interim director.

The center seeks to advance the national conversation on and scholarship of Native Americans and Indigenous peoples and expand on Dickenson’s Carlisle Indian Center Digital Resource Center, a searchable database of school records housed at the U.S. National Archives as part of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“This is an opportunity for Dickinson to turn boldly toward its history and continue the hard work of reconciling with that past, as well as an opportunity for our students and faculty to expand on their voiced interests in Native American and Indigenous studies,” Lone Fight said in a statement on the college website.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported the Center received an $8 million grant. VOA regrets the error.

Read more:

Family seeks justice in killing of Two-Spirit Lakota woman

Buzzfeed News reports this week on the case of Acey Morrison, a 30-year-old Two-Spirit person who was fatally shot in Rapid City, South Dakota.

As VOA has previously reported, Two-Spirit is a “pan-Indian” term for historic and contemporary indigenous people who don’t fit into normative gender roles. [[ HYPERLINK: https://www.voanews.com/a/native-american-two-spirits-look-to-reclaim-lost-heritage/4440354.html

Morrison was shot in the chest by a man she’d met online. The shooter, not identified, said he fired in self-defense, but family members say that doesn’t explain why her body was battered and bruised. They are calling on Rapid City law enforcement to investigate the matter as a homicide.

The story highlights the routine violence Two Spirit people face; Morrison was the 30th transgender person to die violently in 2022, and eight more would die violently by the end of the year, most of them persons of color.

Read more:

Muckleshoot Tribe Logo to grace hockey team jerseys

The Muckleshoot Indian Tribe in Washington State this week became the first Native American tribe to be honored by a professional sports team. The National Hockey League’s Seattle Kraken announced Wednesday that team jerseys will now feature a patch bearing the Tribe’s logo of a snow-covered Mt. Rainier.

“This joyful day brings with it a sense of hope, that our young people will see themselves represented by the team in the heart of Seattle and around the country with our Tribe’s logo on the front of every Kraken jersey,” said Muckleshoot Tribal Chairman Jaison Elkins in a press release.

As part of the partnership, a multi-sport court will be built on the Muckleshoot Reservation.

The Muckleshoot are a federally recognized tribe comprised of descendants of the Duwamish and Upper Puyallup, coastal Salish people who occupied the area around the Puget Sound for thousands of years before European settlement.

Read more:

Indigenous Americans: The continent’s first paleontologists

Smithsonian magazine this week reports that that it was Black and Native Americans who first correctly identified millennia-old fossils.

When European colonists first encountered dinosaur fossils in America, they thought they belonged to a race of giants killed in the biblical flood. Enslaved Africans, however, noted the fossils similarity to elephant bones. And Native Americans preserved long-standing oral traditions of huge animals – “water monsters,” thunderbirds and “grandfathers of the buffalo” – that had once populated the land, water and sky.

Read more:

Native American News Roundup Feb. 12-18, 2023

Here is a summary of some Native American-related stories making headlines this week:

Native American lawyer tapped as Haaland advisor

U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland has a new top policy advisor who is a Native American attorney. Lynn Trujillo, a member of the Sandia Pueblo in New Mexico with ties to the Acoma and Taos Pueblos, most recently led New Mexico’s Indian Affairs Department for Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham.

Prior to that appointment in Santa Fe, Trujillo worked with Native American tribes and organizations as a national Native American coordinator for USDA Rural Development programs. Her past experiences also include organizing in Tribal communities and practicing Indian Law in Washington D.C. and New Mexico.

Read more:

Native Americans: Time to Chop the Chop

The Kansas City Chiefs are National Football League champions, beating the Philadelphia Eagles to win Super Bowl LVII in Glendale, Arizona.

Native Americans were happy to see that this year’s marquee art—designed by Lucinda “La Morena” Hinojos, a Chicana artist who claims Yaqui, Apache and Pima heritage—paid tribute to Indigenous communities in Arizona. Further, during the pre-game ceremony, Navajo citizen Collin Denny signed “America the Beautiful” using a blend of American Sign Language and North American Indian Sign Language.

But many Native Americans were unhappy that despite long-standing objections to Native American mascots and iconography in sports, the Kansas City team has not changed its name. Nor have fans given up the so-called “tomahawk chop,” in which spectators hack at the air and sing a “war chant” rooted in a 1950s children’s cartoon show that stereotyped Indians.

The Chiefs banned headdresses and Native-themed face paint from the stadium in 2020. A year later, they retired their mascot, a horse named “Warpaint.” The Chiefs also said they would review other inappropriate practices, including the chop, which they renamed the “Arrowhead Chop.”

See this video report from USA Today:

Abortion Services Are Inaccessible to Many Native American Women

It was never easy for Native American women to access abortion services. The Indian Health Service, funded by the federal government, is not allowed to perform abortions except in cases of rape, incest or threats to a mother’s life.

Today, nearly eight months after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling on abortion, states have imposed further restrictions, making access to abortion almost impossible.

Read more:

Museum to Digitize Records of Native, Black Revolutionary War Soldiers

The Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia is in the process of digitizing nearly 200 rare documents that detail the names of Native American and Black soldiers who served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

"At least 5,000 men of color fought in the Continental Army, but their stories aren't as known as they should be," said museum president and CEO R. Scott Stephenson. "This archive allows us to explore the extraordinary lives of men who helped to secure independence, yet who have not received the recognition they deserve as American Founders.”

Once complete, the Patriots of Color archive will be free online thanks to funding from the Ancestry.com genealogy website.

The museum purchased the documents last year from a private collection.

Despite their efforts to remain neutral during the Revolutionary War, Native Americans were pulled into the conflict and ended up fighting on both sides — for both the colonists and for the British.

Read more:

Which Cherokee tribe should send delegate to Washington?

The 1835 Treaty of Enchota promised that the Cherokees “shall be entitled to a delegate in the House of Representatives of the United States whenever Congress shall make provision for the same."

Nearly 200 years later, the Cherokee people are calling for Congress to make good on that promise. But there’s a problem. The U.S. federal government recognizes three Cherokee tribes: the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma, the Cherokee Nation Oklahoma and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina.

Which tribe should get the delegate seat? VOA reporter Maxim Moskalkov has this video report:

- By VOA News

Leonard Peltier Remembered on Monday

February 6 is the Global Day of Solidarity with Leonard Peltier, a Native American activist who has been imprisoned for almost five decades.

Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas Director at Amnesty International, said in a statement that “people around the world are calling on President Biden to finally grant Leonard clemency.” She said February 6 “marks the beginning of Leonard’s 48th year of incarceration.”

Peltier, who is 78, has been repeatedly denied parole.

He was a leader in the American Indian Movement when he was arrested, following a shoot out on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota in 1975 in which two FBI agents were killed.

There were several inconsistencies in his case, but he was found guilty and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences.

Before his court case began, he fled the country, fearing that he would not receive a fair trial, but he was found in Canada.

Two other men facing the same charges as Peltier were found not guilty.

“Amnesty International has long maintained that there are serious concerns about the fairness of proceedings leading to his trial and conviction,” Guevara-Rosas said in a statement.

“As President Biden prepares to address the public on Tuesday at the State of the Union Address,” she said, “we urge the administration to uphold their commitment to human rights and grant Leonard Peltier clemency on humanitarian grounds and as a matter of justice.”

Native American News Roundup Jan. 22 - 28, 2023

Here is a summary of some Native American-related stories making headlines this week:

No mining in northern Minnesota forest for at least 2 decades

U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland signed a new order this week that will protect more than 91,000 hectares in Minnesota's Superior National Forest from mineral leasing for 20 years "subject to valid existing rights."

Public Land Order No. 7917 will protect parts of the Rainy River watershed, including lands ceded to the Chippewa Bands of Native Americans in 1854. It also protects the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, the site of a proposed copper-nickel mine.

Environmentalists say mining for minerals including copper, cobalt and nickel would produce tailings that can be dangerous sources of toxic chemicals that would threaten the Rainy River Watershed and the Boundary Waters.

In 2021, the U.S. Forest Service called for a full study of the potential impacts of the proposed copper-nickel mine. The company, Twin Metals, said it was "deeply disappointed" by the move and sued to reclaim mining leases in the area.

"The Department of the Interior takes seriously our obligations to steward public lands and waters on behalf of all Americans. Protecting a place like Boundary Waters is key to supporting the health of the watershed and its surrounding wildlife, upholding our Tribal trust and treaty responsibilities, and boosting the local recreation economy," Haaland said in a statement to the press. "With an eye toward protecting this special place for future generations, I have made this decision using the best-available science and extensive public input."

Read more:

South Dakota tribes say state governor waited too long to help

The Sicangu Lakota of the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota are grieving the loss of six tribe members who died during a multiday snowstorm in mid-December and complain that state officials didn't do enough.

Victims of the weather included an elder who froze to death in his home and a 12-year-old boy who died of a respiratory infection before an ambulance could reach him.

The tribe declared a state of emergency December 16 and appealed to the state for assistance. Governor Kristi Noem activated the National Guard on December 22 to help remove snow and deliver firewood.

In a State of the Tribes speech to state lawmakers January 12, Crow Creek Sioux Tribe Chairman Peter Lengkeek criticized the state's emergency services as "slow to react." The governor's spokesman, Ian Fury, posted a rebuttal on Twitter: "It's a shame that Chairman Lengkeek chose to perpetuate a false narrative."

Read more:

British historian re-examines Age of Discovery

Tens of thousands of Indigenous Americans crossed the Atlantic before Britain founded its first colony in Virginia, traveling as diplomats, slaves and occasionally spouses and/or children of European men.

Smithsonian magazine this week reviews "On Savage Shores: How Indigenous Americans Discovered Europe" and interviews its author, University of Sheffield (U.K.) historian Caroline Dodds Pennock.

"We know from the records that there were Indigenous people in rural Europe, across the Normandy coast of France, across Seville and the connected trans-Atlantic networks in Portugal, in Antwerp, in England," Pennock says, citing examples from her book.

One of them, an Indigenous woman, traveled to Spain with a man named Pedro.

After several years, Pedro married a Spanish woman, who then tried to claim that the Indigenous woman named Isabel and her two sons, Lorenzo and Gaspar, were slaves. In 1570, they appealed to the crown and won both their freedom and monetary compensation.

"It was really important for me to focus on the early period where we see the beginnings of globalization," Pennock said.

These stories, she added, "speak to a bigger story that is incredibly relevant right now, about the origins of our world as an entangled, cosmopolitan place."

Read more:

Ojibwe Snow Snaking returns to Wisconsin island

Next Month, Ojibwe athletes will hold winter games on an island in Lake Superior for the second time in 150 years. Madeline Island is the largest of the Apostle Islands in Lake Superior and has long been an Ojibwe spiritual center. In the 19th century, the government banned tribes from playing winter games there because betting was taking place.

On February 11, players will converge on the island to compete in a game played by many Great Lakes tribes, Snow Snakes. The game involves carving and polishing sticks of various lengths – the "snakes" – then shooting them like javelins down a trough carved into the snow. The snake that glides the furthest wins.

In another variation of the games, players throw the sticks like javelins. Watch the game in action in the video below.

Read more:

Native American News Roundup Jan. 15-21, 2023

Here is a summary of some of the top Native American-related news stories this week:

Former FBI agent petitions White House to release Leonard Peltier

A retired FBI agent who was directly involved in the case against former American Indian Movement leader Leonard Peltier has appealed to President Joe Biden, arguing for Peltier's release.

As VOA reported in 2016, Peltier, an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa tribe of Lakota and Dakota descent, was convicted in the murders of two FBI agents during a 1975 standoff at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences.

Peltier, 78 and in ill health, has spent 46 years in confinement and lost numerous appeals and petitions for parole.

"Retribution seems to have emerged as the primary if not sole reason for continuing what looks from the outside to have become an emotion-driven 'FBI Family' vendetta," former agent Coleen Rowley said in her letter to Biden, which was shared exclusively with London's Guardian newspaper.

Amnesty International and the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention support ending his confinement.

But FBI director Christopher Wray opposes clemency for Peltier, calling him a "ruthless murderer" who shows no remorse for his crime.

Read more:

Muscogee tribal newspaper vs. Muscogee government: new documentary highlights their fight

Premiering at the Sundance Film Festival this weekend is a documentary that chronicles one tribal newspaper's fight for press freedom.

As VOA reported previously, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma established in 2015 an independent media organization, Mvskoke Media (MM), and set up an independent editorial board to protect against interference from the tribal government.

Three years later, the tribal council repealed the law and placed the outlet under the tribe's executive branch.

"Bad Press," co-directed by Rebecca Landsberry-Baker, a Muscogee journalist and executive director of the Native American Journalists Association, and filmmaker Joe Peeler documents efforts by MM reporters to counter what they call "tyranny."

Read Salon's recent interview with Landsberry-Baker here:

To register for an online viewing January 24, click here:

Alaska Natives outraged over botched translation job

The Federal Emergency Management Agency has fired a California company it hired to produce and translate documents that would assist Yup'ik and Inupiaq peoples applying for emergency aid.

Instead of an accurate translation, however, they found complete nonsense: "Tomorrow he will go hunting very early, and will [bring] nothing," read one passage. "Your husband is a polar bear, skinny," read another.

As it turns out, the company pulled random words from English translations of field notes taken by a Russian linguist studying Yup'ik dialects in Siberia's Chukotka peninsula 70 years ago.

For Alaska Natives trying to rebuild after a devastating typhoon last September, it was a double insult and a painful reminder of the past.

"When my mother was beaten for speaking her language in school … to then have the federal government distributing literature representing that it is an Alaska Native language, I can't even describe the emotion behind that sort of symbolism," said Tara Sweeney, Inupiaq, who served as an assistant secretary of Indian Affairs in the Interior Department during the previous administration, The Anchorage Daily News reported.

Read more:

Behring Strait land bridge wasn't a one-way street

The traditional understanding of the origins of most Native Americans is that 12,000-13,000 years ago, shrinking sea levels created a temporary land bridge linking Siberia and Alaska. This allowed small groups of people — the ancestors of modern Native Americans — to leave their homes behind forever and establish thriving populations across North America.

But a new study published in the journal Current Biology shows that humans coming from Siberia's Kamchatka Peninsula had a mixture of genetic backgrounds; some even had links to the Japanese archipelago.

Moreover, DNA sampling suggests that it wasn't a one-way trip — humans traveled back and forth between Alaska and Siberia for thousands of years, even after glaciers melted and the Bering land bridge was once again submerged.

Read more in the journal Science:

Student newspaper to give up Indigenous mascot

A student-run newspaper in a Massachusetts high school has announced that after several years of deliberation they will change the name of their newspaper. For 130 years, Brookline High School's student newspaper has been The Sagamore, derived from an Algonquian word for a tribal leader.

"Continuing to use the name actively disregards the meaning of the word and the history that surrounds it, thereby harming Indigenous communities," reads an editorial on the paper's website.

"Our newspaper aims to be a source of unbiased and relevant news for the school community," the editorial continues. "We hope to represent the community fairly and accurately. With these values in mind, a name like The Sagamore does not make sense. It does not symbolize who we are and it actively counteracts our goal to make all people feel heard and represented on the pages of our paper."

Students made the decision after consultations with the Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag, a cultural heritage group that is not recognized by the federal government or the state of Massachusetts.

Read more:

This week on "The Inside Story," VOA reporter Natasha Mozgovaya looks at the 150th anniversary celebration of Yellowstone National Park and what it means to Native American tribes with historic ties to the land.

Native American News Roundup January 8 – 14, 2023

Here is a summary of some of the top Native American-related news making headlines this week:

Montana lawmaker backs down on resolution questioning Indian reservation system

Facing strong opposition from Montana tribes, a state senator has backed away from introducing a draft resolution calling for Congress to rethink the Indian reservation system.

Last week, State Senator Keith Regier proposed that the Indian reservation system was race-based, created in a “different time and place and under circumstances that no longer exist” and therefore had no place in the modern state, nation and world.

The draft called on the legislature to find that the “Indian reservation system has clearly failed to positively enhance the lives and well-being of most of the Indians or the other citizens of the State of Montana … and failed to positively enhance the lives and well-being of most of the Indians or the other citizens of the State of Montana.”

Monday, Regier said he had changed his mind after “productive conversations” with fellow state senator Shane Morigeau, a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

Read more:

ProPublica and NBC launch collaborative investigation into NAGPRA compliance

The U.S. Interior Department (DOI) and its sub-institutions have the ninth largest collection of unrepatriated Native American remains in the Nation, according to a joint ProPublica/NBC investigation into why the remains of 110,000 Native American, Native Hawaiian and Alaska Natives ancestors are still held by museums, universities and federal agencies more than two decades after the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) became law.

NAGPRA directs all federally-funded museums and federal agencies to catalogue all Native American human remains, funerary items, and objects of cultural significance in their collections, submit the information to a National Park Service database, and work with tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations to repatriate them.

Hurdles include proving an item’s cultural affiliation with a particular tribe or community and the requirement that tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations must request the return of these items.

DOI told ProPublica that it complies with each of its legal obligations under existing regulations, subject to available funding.

“Under the current regulations, the bureaus are not required to consult or repatriate ‘culturally unidentifiable human remains’ unless requested by a Tribe or Native Hawaiian Organization,” it continued. “The Biden-Harris administration prioritizes repatriation, and the Department hopes that its proposed regulatory revisions to NAGPRA will help to address the existing backlog.”

The DOI is not alone. Six other federal agencies have made remains available, including the Departments of Defense and of State, along with hundreds of museums and universities. In other cases, some institutions have used a loophole in the law that allows them to retain artifacts if they deem them “culturally unidentifiable.” The report says the University of California at Berkeley tops that list with the remains of at least 9,000 Native Americans that have not been made available for return to tribes.

The project includes a searchable database and invites institutions and the public to submit tips, including anonymously.

Reports looks to curb overincarceration of Native Americans/Alaska Natives

The MacArthur Foundation has released a report showing that Native Americans are sentenced more harshly than white, Black or Hispanic offenders.

The report, “Over-Incarceration of Native Americans: Roots, Inequities, and Solutions,” says Native Americans and Alaska Natives (AI/AN) are “disproportionate represented” in state and federal criminal justice systems. But it notes that collecting accurate data is challenging: Often, prosecutors lump offenders into an “other” racial category; states and counties may not track race at all or may lack access to justice databases.

“Despite unclear and incomplete data, information suggests that once Native people enter the justice system, it becomes much more difficult for them to get out,” the report states.

Researchers point to a system that could help reduce disparities: Holistic defense, a system that defenders in the Bronx, New York, designed in 1997. This method looks at what drives offenders into the criminal justice system and “fits well with traditional, tribal principles.”

Read report here:

How tribes are using federal COVID aid to benefit citizens

Bloomberg media this week looked at how AI/ANs are using $20 billion in federal pandemic relief, the largest ever single infusion of federal funds into Indian Country.

Examples include:

The Menominee Indian Tribe in Wisconsin is building so-called “tiny homes” for low-income elders and unhoused tribal citizens.

The Walker River Paiute Tribe in rural Nevada is expanding its food pantry.

The Douglas Indian Association in Juneau, Alaska, has set up grants to help Native fisher men and women in the face of rising fuel prices, transportation restrictions and shrinking salmon populations.

After 132 Years, Wounded Knee Artifacts Come Home

Editor’s Note: Some readers may find this content to be triggering.

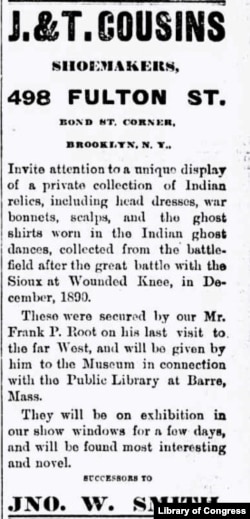

Part 1 of this series looked at the circumstances leading to a massacre of Lakota men, women and children at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on December 29, 1890. In November, a museum in Barre, Massachusetts, repatriated more than 150 objects believed to have been looted from the massacre site. VOA dug through historic records and archives to trace how and when they were obtained, how they made their way to New England, and more than a century later, back to the Lakota.

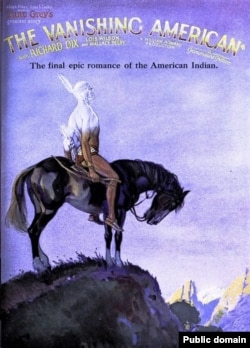

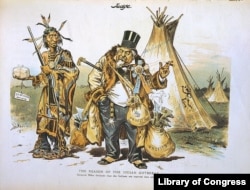

Native American remains and artifacts have always held a fascination for non-Native Americans.

In the 1780s, former U.S. President Thomas Jefferson excavated Native burial sites in Virginia, earning himself the nickname “father of American archaeology.”

In the decades that followed, amateur archaeologists excavated hundreds of burial mounds across America, selling bones and artifacts to museums and private collectors.

The massacre at Wounded Knee ignited what one Nebraska newspaper called days later a “relics craze.” But why?

“Part of it came from this problematic idea that Native American communities were disappearing,” said Aaron Miller, associate curator of visual and material culture at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum in Massachusetts. “You began to see both museums and collectors acquiring these objects to show this idea — this false idea — of what once ‘was.’”

Scavengers

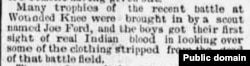

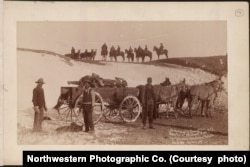

The smoke of Hotchkiss guns had barely cleared when members of the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry began picking through the bodies of the fallen, retrieving “souvenirs” of the 1890 massacre.

The next morning, a group of townsmen from Chadron, Nebraska, got a military pass and hired a coach to race more than 130 kilometers to Wounded Knee. Among them was local photographer Gus Trager, who would achieve fame for his photograph of slain Chief Si Tanka — “Big Foot.”

Ten days later, Trager and town barber Joe Ford had amassed what a local newspaper called “the finest and rarest collection of war dresses, ghost shirts, trinkets, moccasins, etc., now on earth,” including “the entire outfit of Chief Big Foot and the old Medicine Man who brought on the great fight.”

When the Nebraska National Guard was called to nearby towns shortly after the massacre, young guardsmen also joined the relics “craze.”

Omaha Daily Bee correspondent Charles H. Cressy was one of three reporters on the scene at Wounded Knee when the massacre began. Three weeks later, his newspaper reported that items he brought from the site were now on display in an Omaha shop window.

The demand for relics grew, and by mid-February 1891, The Dayton Herald of Ohio noted that many western towns, especially Omaha, were filled with “itinerant vendors of souvenirs of the fight at Wounded Knee.”

“For a moderate investment of cash, the Eastern “tenderfoot” [newcomer] can procure any sort of a relic,” the article said.

To meet demand, some individuals manufactured counterfeit relics, according to the Pickens County Herald and West Alabamian. The newspaper reported that a Chadron journalist attempted to fool a prospective buyer by manufacturing a “ghost shirt” from a stamped hotel bedsheet. It was the ink stamp that gave him away.

The Tenderfoot from Massachusetts

Traveling shoe salesman Francis Pitkin Root arrived in Omaha just as troops were returning from the “Sioux war.” He purchased a considerable collection from Pine Ridge Agency transportation manager Cornelius “Nealy” Williams, who had ferried U.S. troops to and from the front and was later paid to cart Lakota bodies to a nearby burial trench.

According to a July 19, 1891, account in the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper, Root bought:

- A bearskin war bonnet crowned with a circlet of bristles, out of which rose a dyed red eagle feather; it was trimmed with two ponytails and, at the back, a yard-long [nearly 1 meter] “scalp of a white woman.”

- A buckskin war shirt “worn by a chief in the camp of Sitting Bull,” decorated with dyed porcupine quills with matching beaded elk hide leggings.

- A Navajo blanket trimmed in eagle feathers.

- A scalp “torn from the head of an Indian warrior,” with flesh intact.

- A “skeleton” saddle, covered in rawhide, which had bloodstains on the pommel.

- Moccasins taken from the feet of Chief Flying Horse.

- A Ghost shirt decorated with hand-painted thunderbirds — which 19th century writers described as “devil birds” or “harpies,” and a foot-long [0.3-meter] scalp of “coarse black hair.”

- A blue “papoose sack” (cradleboard), trimmed with thousands of tiny beads; a pink basket; a combination pipe/tomahawk, a necklace of 50 deer hooves; bows, arrows, and photographs of Sitting Bull and other leaders.

By that summer, some of Root’s items were on display in shoe store windows in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Brooklyn, New York. By late December, the artifacts were on view at a department store in Boston, where newspapers noted that they would shortly be placed on permanent loan at “a museum in connection with a public library” in Barre, Massachusetts.

Recovery

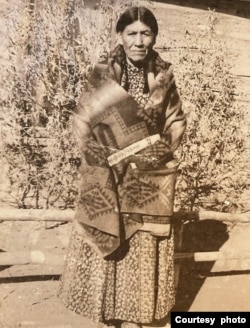

Nearly 100 years later, former Oglala President Alex White Plume got a phone call.

“In the summer of 1990, a lady called me from Massachusetts and said, ‘Do you know that the clothing of all the dead people at Wounded Knee is up here in the museum at Barre?’ That just shocked me. Oh! It was hard to bear.”

White Plume flew to Massachusetts with his aunt and uncle.

“We went in and could just sense the spirits,” White Plume said. “I saw a clump of hair, and I said, ‘This is Bigfoot's hair!’ And little baby clothes, totally beaded, just beautiful designs. And then you’d look at the back part, there would be a big black hole where the bullet exited the body.”

The Oglala Sioux Tribe asked author and activist Mia Feroleto to help negotiate the items’ return from the Barre Founders Museum. She told VOA she was stunned to find how little they had deteriorated after more than a century stored in a building without heat or air conditioning.

“The colors were as bright as they would have been the day before the massacre 130 years ago,” Feroleto said. “The energy in these objects, to my mind is a testament of the spirit of the people, because they were perfectly preserved.”

In November 2022, Oglala and Miniconjou Lakota gathered in the cafeteria of a Barre elementary school for a ceremony to reclaim the artifacts, joined by members of the local Mashpee Wampanoag tribe and the state-recognized Nipmuc tribe.

The items are currently being stored at the Oglala Lakota College in Kyle, South Dakota, where they will remain for the foreseeable future.

In the coming months, descendants will work to decide the fate of their ancestors’ belongings. Should they be turned over to the Miniconjou at Cheyenne River, whose ancestors made up most of the massacre victims? What about the Hunkpapa from Standing Rock, who also lost ancestors at Wounded Knee?

And the items themselves: Should they be buried with the victims or burned according to traditional Lakota burial practices?

Nearly everyone involved agrees that what matters most is finally releasing the spirits of those ancestors.

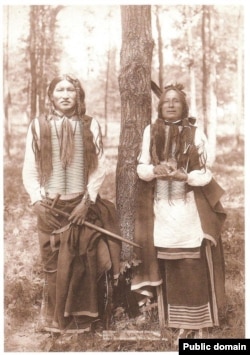

Lakota Descendants Remember Ancestors Killed at Wounded Knee

Lakota from reservations across South Dakota gathered at the Wounded Knee Cemetery on the Pine Ridge Reservation to commemorate ancestors massacred by the U.S. Cavalry in 1890.

On top of 2-foot snowdrifts at the cemetery on December 29, 2022, lay a collection of cardboard boxes containing artifacts and items of clothing believed to have been ripped from the victims’ bodies. After years of negotiations, the items were returned to the Lakota by a small museum in Barre, Massachusetts.

Museum records show only that a traveling shoe salesman from Barre acquired the items on a trip West in 1891 and donated them to the Barre Museum a few years later.

Now on the cold December day, spiritual leaders Richard Moves Camp, an Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge, and Ivan Looking Horse, a Miniconjou from the Cheyenne River Reservation, led the gathering in prayer and a ritual feeding of the spirits.

Later, dozens of Lakota gathered in the warmth of a nearby school where they shared family histories of the massacre, viewed photos of the returned artifacts, and honored the dead.

VOA spent weeks digging through historic records and newspaper accounts to find out more.

Background

In the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, the U.S. government set aside 233,000 square kilometers west of the Missouri River for the “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota tribes, collectively known as the Sioux.

When Lieutenant General George Custer and his 7th Cavalry confirmed there was gold in the Black Hills of that area, prospectors rushed in. By 1875, the Bureau of Indian Affairs ordered the tribes to move. When they resisted, the U.S. government sent in troops, setting off armed conflict that would see Custer defeated.

By 1889, the various bands of Lakota were consigned to separate reservations, with their old ways of life forbidden and the buffalo, which had sustained them for thousands of years, gone.

Subsisting on inadequate government rations of beef, they looked for a miracle.

The ghost dance

In 1890, the Lakota heard about a Paiute man in Nevada who had a vision while cutting wood for his white employer. He fell and died, and God lifted him to heaven. There, he saw white and Native people, made young again, “dancing, gambling, playing ball and having all kinds of sports.”

That vision sparked the Ghost Dance, based on beliefs that if men were good, worked hard, didn’t fight and danced for five nights in succession, God would bring the dead back to life and restore to the Indians their former ways of life. White men would vanish, but details weren’t clear.

To learn more, the Lakota sent Miniconjou chief Kicking Bear and a Sicangu Lakota from The Rosebud Agency named Short Bull to Nevada.

“They didn’t all speak English,” said Ernie LaPointe, the closest living direct descendant of Chief Sitting Bull. “So, they had to speak with hand signals.”

The message that the duo brought back from Nevada lost something in the translation.

“They told the Indians that they had been up near Salt Lake, Utah, to visit the new Messiah,” U.S. agent at Pine Ridge Daniel Royer telegrammed Washington, “and they were told by him … that a new Earth would be formed and would pass over this one, burying the whites beneath.”

“It was Kicking Bear and Short Bull who conjured up this story that if Indians wore these ghost shirts, that a white man's bullets would never hurt them,” said LaPointe. He believes the men got the idea from Mormon colonists in Nevada, who wore white “temple garments” to protect them against temptation and spiritual evil.

Within weeks, hundreds gathered to dance. Some Indian agents and military officials viewed it as a harmless diversion; others believed the tribes were gearing up for insurrection.

Royer again telegrammed Washington: “Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy. … We need protection, and we need it now.”

The White House answered by sending in several thousand troops.

Tipping point

Indian agent James McLaughlin believed Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull was “the high priest” and chief instigator of the “Messiah craze.” He visited Sitting Bull at his cabin near the Grand River and asked him to stop the “absurd craze.” Sitting Bull refused.

“My great grandfather knew that his ghost dance was not a Lakota sacred ceremony. But he had to give his hope to his people, so he allowed them to do this,” LaPointe said.

Sitting Bull decided to violate a travel ban and go to Pine Ridge to confer with Chief Red Cloud about easing tensions.

McLaughlin sent tribal police to arrest Sitting Bull on December 16. In the melee that ensued, Sitting Bull was shot dead.

A massacre

Sitting Bull’s half-brother Hupah Gleska, more commonly known as Si Tanka ("Big Foot"), leader of the Miniconjou Lakota, was at the time camped at the Cheyenne River Agency, 160 kilometers to the north.

“He thought the government was going to come after him,” said Michael He Crow, an Oglala Lakota and descendant of Big Foot. “He felt that he was going to be the next one to die because he had a lot of influence among the people there.”

Big Foot and several hundred followers set out for Pine Ridge, but the Army intercepted them and forced them to camp at the tiny village of Wounded Knee.

On December 29, the Army ordered the Lakota to disarm.

"The men and women were separated," said He Crow. "Most of the men were sitting in a council circle and were the first ones killed. And the ones running were mostly women."

What happened to spark the massacre that followed? Some say it was when the medicine man, Yellow Bird, grabbed a handful of dirt from the ground and threw it up into the air.

“He was praying and crying,” a Hohwoju Lakota survivor named Alice Ghost Horse/Kills the Enemy/War Bonnet would later tell her son. “He was saying to the eagles that he wanted to die instead of his people. … He picked up some dirt from the fireplace and threw it in the air and said this is the way he wanted to go back … to dust.”

Others tell a different story.

“When they were taking the guns away from them, there was a man that was deaf,” He Crow said. “They were trying to tell him to put his gun in the middle of the pile, but he held on to the gun and told them, ‘This is the only thing I have to keep food on the table and stay alive. And you're taking this away from me?’”

The gun went off as officers tried to wrestle it away, said He Crow. And that’s when the Army began firing revolving cannons and rifles.

“It was chaos,” Violet Catches, a Hohwoju Lakota from the Cheyenne River Reservation, said. Her grandfather Leon Holy, then around 12, was one of five children who survived the massacre.

As many as 300 Lakota men, women and children died that day; some who were tracked as far as 3 kilometers from the site. Official accounts say the massacre took 20 minutes, but Ghost Horse/Kills the Enemy/War Bonnet said the shooting didn’t stop until after sunset.

They would be buried in a mass pit several days later, but not before they were picked clean of their weapons and belongings, including the ghost shirts on their backs.

NOTE: Part 2 of this story will examine the “relics craze” that followed the massacre and show how dozens of items associated with Wounded Knee ended up in Massachusetts.

Native American News Roundup Jan. 1-7, 2023

Here is a look at some of the top Native American-related stories making headlines this week:

New York nixes bill to protect Native burial sites from desecration

New York’s governor has vetoed a bill that would have protected ancient Native American burial sites from private land developers.

The Protection of Unmarked Graves Act passed the state legislature unanimously in June. It would have required construction companies to stop work on private property if they encountered human remains and set up a committee including the state archaeologist to coordinate their removal and reburial elsewhere.

Gov. Kathy Hochul vetoed the bill on December 30. In a memo she said she recognized the need for a to handle human remains “in a way that is respectful to lineal descendants or culturally affiliated groups,” but vetoed it because she said it failed to “balance the rights of property owners with the interests of the families of lineal descendants and other groups.”

New York, New Jersey and Wyoming are the only U.S. states that do not have laws protecting unmarked graves on private land from being desecrated.

According to Native News Online, there have been several grave desecrations on Long Island. In 2003, a developer unearthed a mass Native burial site on his property, then built a horse barn over the site.

Read more:

Feds to return long-held funds to Klamath Tribes

President Joe Biden has signed a law giving the Klamath Tribes of Oregon self-governance over money that has been held in trust for more than half a century.

In 1954, the federal government terminated its relationship with the Klamath and Modoc Tribes and the Yahooskin Band of Snake Indians — now collectively known as the Klamath Tribes. This occurred during the so-called “termination era,” in which 109 tribes were terminated from federal benefits and lost treaty rights to more than a million acres of timber-rich land.

That land was the subject of legal claims against the U.S. for mismanagement of tribal assets. Tribal funds were set aside by members recorded on the “final roll” taken in 1954 to pursue that litigation. Later, funds the tribes won in judgments against the U.S. were added to the fund.

Congress in 1986 restored federal recognition but held those funds in trust.

The Klamath Tribe Judgement Fund Repeal Act, which became law on December 21, requires the Interior Department to disburse to those funds to the tribe “as soon as practicable after the date of enactment.”

Read more:

Questions, accusations of racism over death of Native woman in South Dakota jail

The family and community in Rapid City, S.D., are grief-stricken and demanding answers in the case of young Lakota woman who died in jail just days after giving birth to a baby.

In May 2021, then-19-year-old Abbey Lynn Steele gave birth to a baby whose urine tested positive for methamphetamine. South Dakota is the only state in the U.S. that makes ingesting a controlled substance a felony. Steele was charged and released, pending trial.

On November 16, 2022, Steele was brought to the Pennington County Jail for failing to comply with conditions of her initial release. The arrest came five days after she had given surgically-assisted birth to a second child. Later that day, she was found not breathing and taken to the hospital and put on life support. She died on December 2.

Her death has opened debate about whether the state’s ingestion law should be changed. The law’s supporters say it holds drug users accountable in a state where meth use is on the rise. Proponents of the bill, including the American Civil Liberties Union, say South Dakota spends a disproportionate amount of money incarcerating people for drug ingestion — money that would be better spent on addiction treatment programs. They also argue that felony convictions make it harder for released prisoners to find work.

Read more:

Colorado beefs up efforts to find Indigenous missing and murdered

Colorado has launched a new statewide alert system to address the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous persons.

“It’s needed, because we … as Indigenous people, have been silenced too long, and abused too long and not taken seriously,” said Daisy Bluestar, a Southern Ute advocate and member of the Missing & Murdered Indigenous Relatives Taskforce of Colorado, which pushed for the new system.

When an Indigenous person is reported missing, law enforcement now has eight hours to alert the Colorado Bureau of Investigation in cases of a missing adult and two hours to report a missing child.

In the case of a missing Indigenous child, an Amber Alert will now go out statewide, messaging residents’ phones; local and state law enforcement, media outlets and other stakeholders will then be alerted.

Read more:

California bill would speed up university repatriations of remains, artifacts

In a related story, three decades after NAGPRA was enacted, thousands of Native American remains and funerary objects linger in collections across the U.S., many of them at colleges and universities. But these institutions complain the repatriation process is complicated and expensive.

University of California campuses hold hundreds of thousands of remains and artifacts, but a state audit released in November revealed that NAGPRA compliance has been spotty; only two out of the university’s 10 campuses had repatriated the majority of their collections.

State Senator Bill Dodd, a Democrat, has introduced legislation that would require the campuses to allocate sufficient resources for repatriation efforts and to consult with tribes.

“Universities said, ‘We’ll do it, we’ll do it, we don’t need new laws,’” Dodd said. “Well, obviously, we do, because they haven’t been able to adhere to that.”

“The least we can do is budget adequately so that the time and money can be found to return those items to the tribes,” he added.

Read more:

Shawnee Tribe Asks to Take Over Former Boarding School in Kansas

The Shawnee Tribe is asking to take over ownership of a historical site in Kansas that might contain unmarked graves of Native American students.

The tribe released an architectural survey Tuesday that found the three buildings remaining at the Shawnee Indian Mission in Fairway, Kansas, need millions of dollars in repairs, The Kansas City Star reported.

The site, formerly known as the Shawnee Indian Manual Labor School, was one of hundreds of schools run by the government and religious groups in the 1800s and 1900s that removed Indigenous children from their families to assimilate them into white society and Christianity.

It is owned by the Kansas Historical Society. The city of Fairway manages daily operations.

In October, state officials announced that they planned to conduct a ground study to search for unmarked graves on the 4.86-hectare site. That process stalled after the Shawnee Tribe said it had not been consulted enough and raised questions about the proposed study.

Tribal leaders contend that state and Fairway officials have not properly maintained the site.

The Oklahoma-based tribe commissioned the study from Architectural Resources Group last year because leaders are “concerned about the future of this historic site,” Chief Ben Barnes said in a statement Tuesday.

“Over the last year, we have had numerous conversations with the city and state about the need to save this special place,” Barnes said. “When it became clear that there was no plan in place, we began conversations about the possibility of the Shawnee Tribe assuming responsibility for restoring and repairing this site.”

Officials with the Kansas Historical Society and the city of Fairway rejected the suggestion that the site be transferred to the tribe.

Patrick Zollner, acting executive director of the Historical Society, said the organization has already made several improvements, is planning more restoration work and remains committed to telling the history of the site.

In a statement released Tuesday, Fairway officials questioned whether the tribe had the resources to pay for needed renovations and repairs. They also questioned what the tribe would do with the land, and they said the city and state may not have any authority over how the land was used.

Tribal leaders estimate the repairs would cost up to $13 million. If given ownership, the tribe said it would repair the buildings in multiple phases while meeting historical preservation requirements.

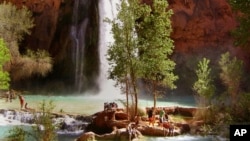

Havasupai Tribe Will Get US Federal 'Flood Damage' Aid

President Joe Biden has approved a disaster declaration made by the Havasupai Tribe in northern Arizona, freeing up funds for flood damage as it prepares to reopen for tourists after nearly three years.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency confirmed Sunday that federal emergency aid will be given to supplement the tribe's own recovery efforts from severe flooding last October.

The funds will be for the tribe and certain nonprofits to share costs for emergency work and repairs from flood damage.