Native Americans

Native American News Roundup April 23-29, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Lawmakers seek to embed Indian child welfare protections into North Dakota law

With only weeks to go before learning the fate of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), North Dakota lawmakers Wednesday approved a bill that would ensure that Native American children in the state's welfare system will be placed with Native American families whenever possible.

ICWA was enacted in 1978 to help prevent the widescale placement of Native children in non-Native homes and institutions.

The U.S. Supreme Court in November heard arguments in Brackeen v. Haaland challenging ICWA as race-based and accusing the federal government of intruding on state affairs. The Court is expected to issue its ruling in late June or early July.

North Dakota Representative Jayme Davis, an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, introduced House Bill 1536 in January to make sure that ICWA is codified in North Dakota law.

The state is home to all or part of five federally recognized tribes where nearly 40 percent of children in foster care identify as Native American.

The bipartisan legislation now goes to Gov. Doug Burgum.

Read more:

Is America's biggest art museum holding stolen or fake Native artifacts?

As part of its ongoing series on the repatriation of Indigenous ancestral remains, ProPublica reported Tuesday that Native American works donated to or on loan to New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art may be stolen or fake.

At issue is a collection of works from more than 50 tribal cultures across North America, some of which date to before European contact. ProPublica found that only 15% of the 139 works donated or loaned by collectors Charles and Valerie Diker have documented histories of ownership, known as provenance.

Further, ProPublica reports that some of the items are culturally sacred or funerary, in violation of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. That law directs all federally funded institutions to catalogue Native American human remains, funerary items and objects of cultural significance and submit them to the National Park Service. They must also notify tribes of these holdings and help effect their repatriation.

The law does not apply to private collections or items on loan.

The Met is the largest art museum in America and operates on an endowment of $2.5 billion.

The report comes just a month after the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists reported that more than 1,100 pieces in the Met's collection were connected to persons who have been indicted or convicted of crimes including looting and trafficking.

Read more:

In the video above, Theland Kicknosway, a member of the Wolf Clan, Potawatami and Cree Nation in Ontario, Canada, explains the significance of long hair to Indigenous North Americans.

Rights groups challenge schools' ban on long hair

The Native American Rights Fund (NARF) this week called on a North Carolina charter school system to reverse a policy mandating that males wear their hair short.

Classical Charter Schools of Leland operates four schools in the state's southeast. According to its handbook, the wearing of "distracting, extreme, radical, or faddish haircuts, hair styles, and colors," are forbidden and hair should be "neatly trimmed and off the collar.

"This School policy is a gross violation of students' religious and cultural beliefs that disproportionately impacts Native American students attending CCSL," reads a letter from NARF sent on Wednesday, one day before the school system met to discuss the matter.

"Since time immemorial, many Tribes and Indigenous communities have placed significant cultural and religious importance on hair and to many is an important aspect of Indigenous identity," NARF attorneys wrote.

NARF joins the American Civil Liberties Union in calling the ban discriminatory.

Read more:

Was Kansas the center of a long-forgotten Native American nation?

A Kansas archaeologist is challenging traditional understandings of precolonial societies of the Great Plains.

Contemporary thinking is that the Plains were home to scattered groups of hunter gatherers. But University of Wichita professor Donald Blakeslee says the Quivira society spanned most of eastern Kansas, northeast Oklahoma and a portion of western Missouri, and was the center of a wheel of trade routes that stretched from Florida through California and into Mexico.

First described as a village by Spanish military explorer Francisco Vazquez de Coronado in the mid-16th century, Blakeslee says Quivira was home to as many as 200,000 people who were ancestors of the present-day Wichita Indians.

"In its day, Quivira was probably the most important native political unit in what's now the United States," Blakeslee said in a university statement in March.

But the Wichita Eagle reported this week that others are skeptical, including the president of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes in Anadarko, Oklahoma, who has asked to see the evidence. The paper also quotes a retired state archaeologist as saying Blakeslee's rewriting history is "a little grandiose."

Blakeslee is currently working on a book manuscript that he says will explain everything.

Read more:

Native American News Roundup April 16-22, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

South Dakota passes controversial social studies standards

South Dakota’s board of education Monday passed new standards for teaching social studies following four public hearings and years of controversy.

“Today is a wonderful day for the students in South Dakota. They are our future,” said Governor Kristi Noem. “Now, they will be taught the best social studies education in the country, one that is a true accounting of our history.”

But 880 pages of comments from current and former educators, parents and members of the public show widespread opposition to the standards, including complaining that the material is far too advanced for grade levels.

While the standards reference Native Americans in general, tribal leaders object to the lack of any specificity about Indigenous social studies.

“We are 24% of the population in South Dakota, and I think the standards should address Dakota, Lakota and Nakota specifically, or else the Oceti Sakowin, which are the Seven Council Fires, which is the collective name for all three,” Sherry Johnson, education director for the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate [tribe],” told VOA.

Read more:

NY to schools: Drop the Native American mascots or face funding cuts

The New York Board of Regents Tuesday unanimously voted to ban the use of Indigenous names, mascots and imagery in all public schools after the end of the 2024-2025 school year.

The National Congress of American Indians, which tracks mascots across the United States, counts 113 schools in 55 districts across New York that will have to change or risk losing state funding. NCAI says the use of Native American mascots and imagery is racist and demeaning.

“The ‘warrior savage’ myth has plagued this country’s relationships with the Indian people, as it reinforces the racist view that Indians are uncivilized and uneducated.”

Some school districts are pushing back, saying the change will be costly and will erase schools’ histories. Republican Representative Elise Stefanik blasted the decision as the product of a “woke agenda.”

“Upstate New York and the North Country take pride in our history, and forcing them to replace these historical mascots is prioritizing the far-left mob at the expense of our students’ education,” she said.

Read more:

Illinois lawmaker seeks to incorporate Indigenous history into the classroom

Illinois State Senator Suzy Glowiak Hilton has introduced legislation to make all public schools incorporate Native American history into their curricula.

“Native American history is American history, and it has been overlooked for far too long,” said Glowiak Hilton. “We need to give our students the opportunities to better understand the discrimination and persecution Native Americans faced throughout history.”

House Bill 1633 would require teaching for grades six through 12 to include “the study of the genocide of and discrimination against Native Americans,” including the concept of tribal sovereignty, treaties made between tribes and the federal government, and federal policies of forced Native American relocation.

Read more:

Mixed signals: Will the Boy Scouts stop ‘playing Indian?’

Last month, the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) sent out a 20-question survey asking present and former members, among other things, whether the organization should keep or eliminate “Native American traditions” from its pageants, rituals and ceremonies.

As VOA has previously reported, Native Americans have long criticized BSA for misappropriating generic “Indian” culture, donning headdresses and taking on “Indian names.” In this video, BSA Order of the Arrow members dance and drum as part of summer camp activities.

“With so many fine traditions of their own, why do the Boy Scouts have to steal ours?” Native rights advocate Suzan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne and Muscogee) asked in a 2019 statement to VOA. “They can learn, teach and promote survival and life skills without ‘playing Indian.’”

BSA told NBC News it has “no plans to eliminate Native American traditions” from its programs.

Read more:

‘Bad Press’ documents tribal reporters’ fight for free speech

In 2018, the Muscogee Nation in Oklahoma revoked press freedoms it guaranteed the tribe’s media outlet Mvskoke Media just three years earlier. The action sparked outrage among the paper’s staff, many of whom walked out.

Former Mvskoke Media reporter Rebecca Landsberry-Baker teamed up with Hollywood filmmaker Joe Peeler to document the struggle to regain lost freedoms. The film debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in January and highlights the struggle tribal newspaper editors face across Indian Country, where fewer than 1% of the 574 federally recognized tribes have laws protecting press freedoms.

Read more:

Lakota playwright opens on Broadway

Sicangu Lakota playwright Larissa FastHorse made her Broadway debut this week with “The Thanksgiving Play.” The last and only other Native American to have a play produced on Broadway was Cherokee citizen Lynn Riggs, whose play “Green Grow the Lilacs,” opened in 1931. [[ HYPERLINK: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/q-and-a/larissa-fasthorse-becomes-the-first-native-american-woman-to-bring-a-show-to-broadway]]

The comedy takes place in a schoolroom, where four teachers struggle to put on a culturally sensitive pageant honoring both Native Americans and the first Thanksgiving at Plymouth.

Watch a clip from the play’s 2018 debut below:

Native American Artist's Work Stolen, Copied Around the World

Like most Facebook users, I am targeted by advertisements relating to my interests, particularly Native American.

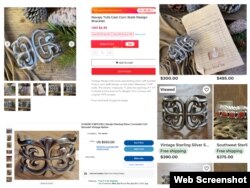

So, when an ad popped up recently advertising a “Navajo Tufa Cast Corn Stalk Design Bracelet” cast from 55 grams of sterling silver, it got my attention, especially because its price was an implausible $6.48.

“Because of Black Friday, we produced … a lot of items, but we can’t sell them all … now we need to pay suppliers a lot of money,” is how the Cuterise website explained the low price.

The Scam Detector website rated Cuterise “Risky. Dubious. Perilous.” But curiosity got the best of me, so I accepted the risk and ordered the bracelet. While waiting for it to ship — if anything shipped at all — I decided to learn everything I could about it.

Tufa casting involves pouring molten silver into a mold carved out of soft volcanic stone found in New Mexico and Arizona. The Navajo have been using it to make jewelry since the mid-1800s.

Tufa is fragile and can crumble after a single casting. For this reason, artists often make a “master” using molten lead instead of silver that can be used to mold and cast multiple copies.

Genealogy of a bracelet

An image search on Google Lens turned up several matching bracelets, ranging in price from $300 to $900, but none were hallmarked by the maker.

I found the identical bracelet on the eBay auction site, which named the maker: Navajo Nation artist Eugene Mitchell. I tracked down his son Reggie Mitchell and sent him the photo of the bracelet I’d ordered. He confirmed that his father made that design in the 1970s.

“Our family has been making jewelry for a long time,” he said. “I’m the fifth generation, and my oldest son Bronson is the sixth.”

And for six generations, he added, his family has helped make Gallup, New Mexico, arts and crafts dealers rich.

“Back in the ‘70s, the FBI investigated Gallup because more 100-dollar bills were circulating there than in all of Las Vegas,” he said. “Gallup produced over 200 millionaires in that seven- to 10-year time period, and the source was Native American jewelry.”

I couldn’t find any data to confirm this, so I reached out to the Gallup McKinley County Chamber of Commerce.

“While the story has circulated in and around our community for years, it is more urban legend than truth,” Chamber of Commerce CEO Bill Lee responded via email. “What I will tell you is that even in today's world of credit/debit cards, Gallup merchants still deal with very high volumes of cash.”

Reggie Mitchell remembers going with his father to Gallup, where he says a dealer “would always try to lowball the value” of his work.

“If it was two pieces of jewelry, they would give him money to make two more pieces and buy two meals,” he said. “And if they paid him, say, $100 for one piece, they’d turn around and sell it for six, seven, $800.”

It was on one of those trips to Gallup that Eugene Mitchell was robbed.

“My dad used to keep his lead masters in old coffee cans,” Mitchell said. “One day, he came out of a shop and discovered someone had broken his car window and taken the cans.”

Mitchell isn’t sure whether the master for the cornstalk bracelet was among the items stolen that day. He says his father found out later that New Mexico galleries were making rubber molds of the designs and selling copies “on the cheap.”

“And my dad would see them and say, ‘That's my work, that’s my piece!’”

After that, the elder Mitchell cut out the middleman, and today, the family sells directly to their customers.

Bait and switch

I was surprised when Cuterise emailed me delivery tracking information. My order originated in Dongguan, China, a city dubbed “the world’s factory” and was now in transit to the U.S.

Clearly, I was going to receive something for my $6.48. But what? A plastic bracelet?

Ten days later, my order arrived. The package was flat and squishy. I tore it open and almost laughed. They’d sent me a pair of cheap stretch leggings printed to look like blue jeans – buttons, rivets and all.

My amusement faded as I thought about everything Reggie Mitchell told me. The family may not be using middlemen anymore, but Eugene Mitchell is still being exploited — this time by fraudsters halfway around the globe using photographs of a bracelet he made — and lost — 50 years ago.

Native American News Roundup April 9-15, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Report: States’ efforts slowing inclusion of race, ethnicity in school teachings

Native American history and cultures have long been left out of American history lessons. Just as U.S. school systems have been redesigning curricula to be more inclusive, the anti-critical race theory (CRT) movement is working to make sure that race, ethnicity, national origin, gender and color are never discussed in U.S. classrooms, The Nation reports.

One hundred ninety-five “educational gag orders” have been introduced in 41 state legislatures since January 2021, according to the nonprofit PEN America. Fifteen states have laws in place, and seven of them censor CRT at the college/university level. These include states such as South Dakota, which have large Native American populations.

CRT is a decades-old academic concept that racism is built into U.S. legal and government systems. In recent years, it has come to be applied to any teaching of America’s racist history, which critics believe creates conflict and places unfair blame on white Americans for the actions of their ancestors.

The American Civil Liberties Union says CRT laws are “thinly veiled attempts to silence discussions of race, gender, and sexuality,” which “suppress free speech.”

Read more:

Montana judge upholds lawsuit on state failure to fund, teach Native history

A Montana judge refused this week to dismiss a lawsuit accusing the state of violating its constitution by failing to teach Native American history and culture to public school students.

Montana is home to seven Indian reservations and eight federally recognized tribes. In 1972, the state amended its constitution, requiring public school teachers to consult with tribes and give instruction about the Indigenous peoples of the state.

In 2007, Montana legislators allocated $3.5 million annually to support Indian education. The current lawsuit, filed in 2021, claims that nearly half of allocations for 2019 and 2020 are unaccounted for.

The state tried to have the case dismissed, but the judge upheld the lawsuit, saying she would explain her reasons next month.

Read more:

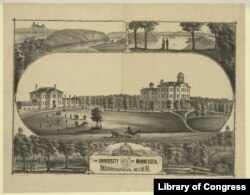

Report: University of Minnesota guilty of ethnic cleansing

A three-year study of the history of the University of Minnesota and its relationship to Native tribes shows how the school was founded on proceeds of land tribes were forced to cede in the 19th century.

A new report, “Towards Recognition and University-Tribal Healing,” or TRUTH, sheds light on the Morrill Act, signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862, that allowed states to establish public colleges paid for by developing land tribal communities had been forced to cede in previous decades.

Digging through archives, a team of researchers found that the U.S. paid $2,309 for 94,631 acres of formerly Dakota and Ojibwe land. The university sold that land and raised nearly $580,000 by the turn of the 20th century, equivalent to more than $18.4 million in 2021.

“The Founding Board of Regents committed genocide and ethnic cleansing … for financial gains,” the authors state, adding that they also “used their positions in government to pass anti-Indigenous legislation that benefited them and the institution financially.”

Authors are calling on the university to formally acknowledge its wrongs and take steps toward healing that include reparations, truth telling and policy changes.

Read the report here:

Yale Launches Cherokee Language Course

Beginning next fall, Yale University will offer a Cherokee language course that will count toward academic credit.

As Native News online reported this week, Yale has offered informal courses in a variety of indigenous languages via its Native American Cultural Center and the Directed Independent Language Study program. But these did not satisfy the foreign language study required in many degree programs.

Read more:

1,000-year-old Indian canoe raised from North Carolina Lake

A team of archaeologists, assisted by members of the nearby state-recognized Waccamaw Siouan Tribe, this week raised an ancient Native American canoe out of a lake in southeastern North Carolina (see video above).

State archaeologists say the canoe is about 1,000 years old, dating to a time when a number of tribal groups lived in the region.

Two teenagers discovered the canoe while swimming in Lake Waccamaw in 2021. They notified state archaeologists, who moved the canoe closer to the shore and stabilized it.

VOA reached out to John Mintz with the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology for details.

“We submitted [a sample] to a lab for carbon-14 dating. The numbers came back between 960 and 940 BCE, so we rounded it up to about a thousand years old,” Mintz said.

He explained how the 28-foot dugout canoe survived so long underwater without rotting.

“Wood, once it’s immersed in water or mud or a combination thereof, can reach a certain equilibrium where there’s no more degradation, no more rot. It can just stay that way — obviously for a thousand years or more,” he said. “But once wood is brought up out of that medium and begins to dry, it will rot before your eyes.”

Archaeologists placed the canoe into a specially designed tank full of water. Over time, Mintz said, conservationists will draw the water out and replace it with a chemical bonding agent to hold the wood together.

Read more:

Ojibwe Woman Makes History as North Dakota Poet Laureate

North Dakota lawmakers have appointed an Ojibwe woman as the state's poet laureate, making her the first Native American to hold the position in the state and increasing attention to her expertise on the troubled history of Native American boarding schools.

Denise Lajimodiere, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band in Belcourt, has written several award-winning books of poetry. She's considered a national expert on the history of Native American boarding schools and wrote an academic book called Stringing Rosaries in 2019 on the atrocities experienced by boarding school survivors.

"I'm honored and humbled to represent my tribe. They are and always will be my inspiration," Lajimodiere said in an interview, following a bipartisan confirmation of her two-year term as poet laureate on Wednesday.

Poet laureates represent the state in inaugural speeches, commencements, poetry readings and educational events, said Kim Konikow, executive director of the North Dakota Council on the Arts.

Lajimodiere, an educator who earned her doctorate degree from the University of North Dakota, said she plans to leverage her role as poet laureate to hold workshops with Native students around the state. She wants to develop a new book that focuses on them.

Lajimodiere's appointment is impactful and inspirational because "representation counts at all levels," said Nicole Donaghy, executive director of the advocacy group North Dakota Native Vote and a Hunkpapa Lakota from the Standing Rock Nation.

The more Native Americans can see themselves in positions of honor, the better it is for our communities, Donaghy said.

"I've grown up knowing how amazing she is," said Rep. Jayme Davis, a Democrat of Rolette, who is from the same Turtle Mountain Band as Lajimodiere. "In my mind, there's nobody more deserving."

By spotlighting personal accounts of what boarding school survivors experienced, Lajimodiere's book Stringing Rosaries sparked discussions on how to address injustices Native people have experienced, Davis said.

From the 18th century and continuing as late as the 1960s, networks of boarding schools institutionalized the legal kidnapping, abuse and forced cultural assimilation of Indigenous children in North America. Much of Lajimodiere's work grapples with trauma as it was felt by Native people in the region.

"Sap seeps down a fir tree's trunk like bitter tears.... I brace against the tree and weep for the children, for the parents left behind, for my father who lived, for those who didn't," Lajimodiere wrote in a poem based on interviews with boarding school victims, published in her 2016 book Bitter Tears.

Davis, the legislator, said Lajimodiere's writing informs ongoing work to grapple with the past like returning ancestral remains — including boarding school victims — and protecting tribal cultures going forward by codifying the federal Indian Child Welfare Act into state law.

The law, enacted in 1978, gives tribes power in foster care and adoption proceedings involving Native children. North Dakota and several other states have considered codifying it this year, as the U.S. Supreme Court considers a challenge to the federal law.

The U.S. Department of the Interior released a report last year that identified more than 400 Native American boarding schools that sought to assimilate Native children into white society. The federal study found that more than 500 students died at the boarding schools but officials expect that figure to grow exponentially as research continues.

Native American News Roundup April 2-8, 2023

Here are some of the Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Veterans Affairs to drop health care copayments for Native American vets

Native Americans and Alaska Natives who have served in the armed forces will no longer have to make copayments for health care and emergency care received through Veterans Affairs.

“American Indian and Alaska Native Veterans deserve access to world-class health care for their courageous service to our nation,” VA Secretary Denis McDonough said in a press release Monday. “By eliminating copays, we are making VA health care more affordable and accessible — which will lead to better health outcomes for these heroes.”

The new rule is estimated to affect about 25,000 American Indian and Alaska Native veterans.

Read more:

Administration takes new steps to help tribe conserve water

The Biden/Harris administration has announced up to $233 million in funding and conservation agreements to help the Gila River Indian Community and water users across the Colorado River Basin protect the stability and sustainability of the Colorado River System during a period of persistent drought.

“Through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act, we have historic, once-in-a-generation investments to expand access to clean drinking water for families, farmers and Tribes,” Deputy Interior Secretary Tommy Beaudreau said in a press release Thursday. “In the wake of record drought throughout the West, safeguarding Tribal access to water resources could not be more critical.”

The Gila River Indian Community in Arizona will receive $50 million to help fund a system conservation agreement to protect Colorado River reservoir storage amid climate change-driven drought conditions. It will also receive $83 million for the community’s Reclaimed Water Pipeline Project.

Read more:

Think tank: feds need to change how they collect data on Native Americans

The Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank, says government methods of collecting and publishing data on race and ethnicity is skewing research, affecting policy and furthering old misunderstandings about Indigenous Americans.

Today, federal race data is usually divided into five categories: white, Black, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. An added category, Hispanic or Latino, is problematic because these are ethnicities, not races. Confusing matters more, Native American is a political and legal classification, not a racial one.

U.S. Census data show that Native Americans identify as two or more races at significantly higher rates than these larger groups. Agencies and institutions often lump multiracial individuals into a single, catch-all category.

This can lead to the exclusion of more than three-quarters of Native Americans from some official data sets, the study says.

The authors do not, however, address the added problem of non-Natives claiming Native American ancestry based on family folklore or so-called “race shifters.”

As the federal government looks toward the 2030 federal Census, Brookings recommends creating a separate set of questions on Native American identity, allowing individuals to specify tribal affiliation.

The Brookings team also suggests that the government should empower tribes to collect and manage data about their own populations and territories.

Read more:

TVA ready to repatriate thousands of Native ancestral remains

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) — the largest federally owned utility company in the U.S. — says it has finished inventorying its collection of Native American human remains and funerary objects and is ready to repatriate them to tribes.

In a Wednesday notice in the Federal Register, the company said it holds the remains of more than 4,800 Native ancestors and 1,400 associated funerary objects collected during dam construction projects in Alabama, Kentucky and Tennessee during the 1930s.

1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) requires all federally funded institutions to consult with tribes to identify and return Native American human remains, funerary objects and objects of cultural or spiritual significance.

The collection is associated with several tribes that once made their home in the region, including the Cherokee, Shawnee, Choctaw and Muscogee. Tribes seeking their repatriation may submit requests after April 28.

Read more:

Study: Indigenous traders, not the Spanish, brought horses to Plains

A study published in the journal Science concludes something Native Americans say they have known all along: Indigenous societies were working with and caring for horses in the Rockies and central Plains before any European set foot in the region.

Horses first evolved in North America 4 million years ago and, according to scientists, became extinct during the Ice Age 10,000 years ago.

The common scientific narrative is that Spanish conquistadors reintroduced horses to North America.

Archaeologists from the Universities of Colorado, New Mexico and Oklahoma worked with Lakota, Comanche, Pawnee and Pueblo collaborators and analyzed and dated the remains of more than two dozen horses across Western states. Their conclusion: Indigenous peoples working through established trade networks brought Spanish horses west.

Many Native Americans, among them Lakota/Cheyenne scholar Yvette Running Horse Collin, maintain that prehistoric horses never went extinct and were here all along.

Read more:

Counterfeit Native American Art Undercuts Legitimate Artists

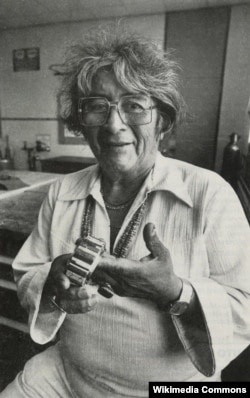

Charles Loloma is regarded as one of the most influential Native American jewelers of the 20th century. The Hopi artist incorporated new designs and materials in rings and necklaces that sell for tens of thousands of dollars and are among the most valuable in Native American jewelry.

Loloma died in 1991. So when previously-unknown Loloma jewelry started showing up on eBay, it looked suspicious to federal agents charged with enforcing the Indian Arts and Crafts Act. Investigators posed as buyers and purchased from California resident Robert Haack $10,000 of what he advertised as genuine Loloma jewelry.

Agents then called Loloma’s niece, Verma Nequatewa, a jeweler who studied under her famous uncle. She traveled from her home on the Hopi Nation to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service forensics laboratory in Oregon to deconstruct the jewelry and certified that it was a fake.

“It just makes me angry,” Nequatewa told VOA. “Some of us artists work very hard to make our living, and people like this just get away with it.”

Haack was indicted on four counts of violating the Indian Arts and Crafts Act. He pleaded guilty in 2021 and is awaiting sentencing.

Nequatewa’s husband, Robert Rhodes, estimates that Haack sold more than one million dollars of fake Loloma jewelry before his arrest.

“It hurts the whole industry of Native American art,” he said. “Because if somebody thinks that they're buying a real Loloma piece and they pay ten thousand dollars for it only to find out it's a fake, they're not going to buy a piece of Indian art again.”

Few prosecutions

The Haack case is one of the few prosecuted by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, which a GAO study found received 649 complaints between 1990 and 2010 and prosecuted five.

"These cases take a great deal of time and resources," said Indian Arts and Crafts Board director Meredith Stanton, an enrolled member of the Delaware Nation of Oklahoma.

The law protects the artistic work of any member of a federal- or state-recognized Indian tribe or anyone whom a federal or state-recognized Indian tribe certifies as an Indian artisan. Products marketed as “Native American style,” however, are not prohibited under the law and may be manufactured and sold by anyone.

Products designed by a Native American but produced by a non-Native American do not qualify as Native-American made. Products manufactured overseas are meant to be indelibly marked to identify their country of origin. But Cherokee historian and activist David Cornsilk says unscrupulous dealers simply peel off those labels and pass off those crafts as “Native made”.

History

The Navajo began producing jewelry in the mid-19th century, obtaining silver from melted down coins and candlesticks.

“We didn’t really have a money system. When we traded and got silver – whether it be through Spanish coins or whatever – we ended up converting that into jewelry,” said Navajo jeweler Reggie Mitchell. “In essence, we were wearing our wealth, and that became our way of bargaining or trading.”

The railroad – and later the automobile – brought curiosity seekers and ethnographers to the American Southwest. Enterprising Navajo, Hopi and other Pueblo artisans found ready buyers for their wares at railway stops in Albuquerque and Santa Fe.

As demand for their crafts grew, Congress passed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1935 (IACA). The law established an Indian Arts and Crafts Board within the Interior Department to help Native craft persons to market their work. The law also made it a misdemeanor to sell imitation products and set penalties at up to $2,000 and/or up to six months in jail.

This did not stop the counterfeiting, however. By 1985, the Commerce Department estimated annual sales of Native American arts and crafts at $400 to $800 million and suggested that cheap imitations imported from Mexico and Asia made up 20 percent of that market.

Congress in 1990 amended IACA, upgrading violations to felonies punishable by up to $250,000 in fines and/or five years in prison for individual violators and fines up to $1,000,000 for businesses.

“The original was directed toward the economy and well-being of American Indians, and the 1990 law was aimed at protecting buyers from fraud," Cornsilk told VOA. “The Internet complicates things because it allows for the buying and selling of items without actually coming in contact with the vendor, so there’s no way to know whether the person selling is legit.”

Native American News Roundup March 26 - April 1, 2023

Here is a summary of Native American-related news around the U.S. this week:

Vatican repudiates legal, ideological concept that drove colonization

The Vatican is rejecting the so-called “Doctrine of Discovery,” an ideological and legal concept rooted in 15th Century papal bulls (directives). Together, they have the Church’s blessing for the European conquest of the New World, the enslavement of “infidels,” and the denial of indigenous land rights.

Many Native Americans and legal analysts say the doctrine underpins U.S. law today. They cite an 1823 Supreme Court case, Johnson v. McIntosh, in which Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that discovery of the New World gave the discoverers a right of title to the land.

“The Church acknowledges that these papal bulls did not adequately reflect the equal dignity and rights of indigenous peoples,” reads the Vatican statement. “The Church is also aware that the contents of these documents were manipulated for political purposes by competing colonial powers…to justify immoral acts against indigenous peoples…at times, without opposition from ecclesiastical authorities.”

Shawnee Lenape scholar and author Steven Newcomb has spent much of his career studying the Doctrine. He expressed some concern with the Vatican statement.

“It’s easy for them to quote the language from the Papal Bull of 1537 because it's favorable language, but they never quote any language from the earlier Papal document to explain what it is we're even complaining about,” he told VOA, referring to a decree by a later pope which said Indians should not be robbed of “liberty or the possession of their property.”

Read Vatican statement here:

Protesters block sale of alleged Native American skull

A North Carolina gallery stopped Saturday’s auction of what was listed as a 600-year-old skull of a Native North American after protests by members of a state-recognized tribe and allied demonstrators.

They cited the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which bans “all trafficking in Native American human remains for sale or profit unless they are excavated or exhumed with the full consent of the next of kin or a tribe or tribal community’s official governing body.”

An archived listing says the skull was purchased in the 1960s from a Montreal antiques gallery and that the 1990 law does not apply because the skull was found prior to 1981.

VOA reached out to Shannon O'Loughlin, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma who is chief executive and attorney for the Association on American Indian Affairs.

“It is not clear whether NAGPRA applies because we only have third-party information, some of it conflicting,” O’Loughlin said via email. “NAGPRA criminal trafficking provisions only apply if the Ancestor was taken from a U.S. ‘museum’ or federal agency after November 16, 1990, to traffic, sell or profit off of it.”

Read more:

Oglala Tribe to AIM: No more celebratory gunfire at Wounded Knee

The Oglala Lakota Sioux Tribal Council on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota has banned the discharge of guns at Wounded Knee, the site of an 1890 massacre of several hundred Lakota men, women and children.

On February 27, 1973, members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) and their allies occupied Wounded Knee for 71 days, protesting tribal leadership and federal Indian policies. The anniversary of the start of the takeover has since been designated as Liberation Day.

AIM activists and supporters mark the date each year with celebrations at Wounded Knee that include firing their weapons (see clip below, courtesy of a tribe member who asked not to be named).

Descendants of massacre victims and survivors have long opposed the practice as profoundly disrespectful.

“My grandfather, he was a survivor of that day,” said Marlis Afraid of Hawk. “And those relatives who were massacred, they are still there. They didn’t cross over. And me, I am their voice.”

Adding insult to injury, she noted, “the people firing the guns don’t even have the decency to pick up their empty shells.”

Watch the Oglala Lakota tribal council vote here:

US Army to repatriate Carlisle student remains

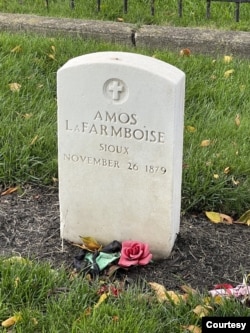

The U.S. Army says it has approved the repatriation of the remains of a Carlisle Indian school student who died 144 years ago.

Amos Laframboise was among the first children sent to the Carlisle Indian School, the first of hundreds of schools designed to strip Native youth of their traditions and to remake them as “civilized” Americans.

He died just 20 days after arriving.

Since 2016, the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservation in South Dakota has fought to have the child’s remains sent home, citing the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

Previously, the Army said that NAGPRA did not apply in this case “because the remains are not part of a collection.” The Army had also called for a signed affidavit from a lineal descendant of the child.

Tribal members say the army notified them this week that Laframboise will be disinterred in September.

Read more:

Lakota artist: ‘We’re still here’

Danielle SeeWalker, a Hunkpapa Lakota artist from the Standing Rock Reservation now living in Colorado, says she is working to give an accurate and insightful representation of contemporary Native American life. Her artwork is on exhibit in the Western U.S. state of Colorado. VOA’s Scott Stearns gives us a look.

Artist Paints Contemporary Native American Life

Artist Danielle SeeWalker says she is attempting to paint an accurate and insightful representation of contemporary Native American life. Her work is on exhibit in the Western U.S. state of Colorado. VOA’s Scott Stearns gives us a look. Camera: Scott Stearns

Navajo Tech First Among US Tribal Universities to Offer PhD

A university on the largest Native American reservation in the U.S. launched its accredited doctoral program, becoming the first among more than 30 accredited tribal colleges and universities across the country to offer such a high-level degree.

The program at Navajo Technical University will be dedicated to sustaining Diné culture and language. Dine is the Navajo word meaning "the people" and is commonly what tribal members call themselves.

A celebration is planned on the Crownpoint campus in western New Mexico in April, and the school already started accepting applications for the fall semester.

The offering marks a milestone for the university, which already has more than 30 degree and certificate programs spanning science, technology, engineering, business and liberal arts, Navajo Tech President Elmer Guy said.

Guy told The Associated Press on Friday that he believes the program in which students will receive a Ph.D. in Dine Culture and Language Sustainability will have a profound impact on the future of the tribe's language and culture. He said he's excited to see how students shape their dissertations.

The idea was to create a program that would lead to employment opportunities and effect change for Navajo communities on the reservation that stretches into New Mexico, Arizona and Utah.

"I thought it would be important to make that connection," Guy said, explaining that it's a step beyond the call by tribal leaders for their people to learn the language and stay engaged with their culture. "Individuals will get a degree and they'll be professionals. You have to make it applicable. By making it more meaningful, people will have an interest in it."

The effort is paying off. About 20 students have applied so far and will be vying for five coveted spots in the inaugural class, said Wafa Hozien, an administrator who helped with the program's creation.

A collaboration with other academic institutions and community partners, the doctoral program was developed with the help of tribal elders, university professors and linguistic experts. Community-based research and internships will be part of the curriculum so students gain practical experience they can apply in the real world.

Guy said he's hopeful this inspires other tribal colleges and universities to create their own programs.

Hozien said Navajo Tech's program represents a paradigm shift in that learning through a Dine lens — with culture and language — creates leaders who can advocate for their people in the judicial system, education, land management, business, technology and health care, for example.

Guy said the work done by the university to train court reporters to document Navajo testimony and translators to help with reading ballots during election season already has addressed some of the pressing needs within communities.

The possibilities will be even greater as students earn doctoral degrees, he said.

"They will be part of solving problems," Guy said. "These students have energy and creativity, and our job is to give them the tools."

Native American News Roundup March 19-25, 2023

Here are some Native American-related news stories that made headlines this week:

Supreme Court weighs Navajo water rights

U.S. Supreme Court justices hearing arguments over Navajo Nation water rights appear divided over who should have water rights to the Colorado River, whose levels have hit historic lows.

At the heart of the cases Arizona v. Navajo Nation and Department of Interior v. Navajo Nation is whether the government has an obligation to provide water under the 1868 Treaty of Bosque Redondo, which established the reservation as a “permanent home” for the Navajo.

In oral arguments Monday, some justices questioned the impact the Navajo Nation request for relief would have on current agreements governing the distribution of Colorado River water during what has been a prolonged drought. Other justices appeared favorable to the Navajo Nation argument that there is an enforceable obligation to provide sufficient water in the federal government’s promise of a Navajo home.

Read more:

VA lowers interest rates for Native American direct loans

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is lowering the interest rate for VA Native American Direct Loans to make housing more affordable for Native Americans who have served.

The VA says new participants in the direct loan program will see their rate decrease from the current 6% to 2.5% for properties on trust land overseen by federally recognized tribes. The new rate will be available for the next two years.

Native Americans buying homes outside of tribal land are not eligible for the program but can use traditional VA home loans.

Native vets already in the program who are paying an interest rate of 3.5% or higher can refinance their loans to the lower rate.

Read more:

Native American honors at White House

A celebrated Native American academic was among 12 recipients of one of the Nation’s highest honors this week. President Joe Biden presented a National Humanities Medal to Henrietta Mann, 88, a citizen of the Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma.

“You know, Henrietta Mann as a teacher, a scholar, and a leader. She’s dedicated her career to Native American education and to establishing the field of Native American studies,” President Joe Biden said in White House ceremony Tuesday. “Thanks in large part to her, Native American studies is now taught in universities across the country, strengthening our nation-to-nation bonds for generations to come.”

The Koahnic Broadcast Corporation also received a medal for its daily public affairs call-in show, “Native America Calling.”

“We are grateful and humbled to receive this recognition for Native America Calling’s service to listeners across the nation, and for Native communities in particular,” said Koahnic’s President and CEO, Jaclyn Sallee, Iñupiaq, who accepted the medal.

The award program, inaugurated in 1997, honors work that has deepened the nation’s understanding of the human experience and expanded citizens' knowledge of history, literature, languages and other humanities.

Read more about Mann’s achievements here:

Listen to Native America Calling here:

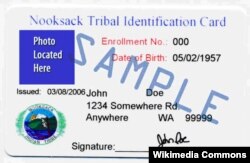

Native Americans could soon use tribal IDs to buy firearms

Republican U.S. Representative Dusty Johnson of South Dakota this week reintroduced bipartisan legislation to make it easier for Native Americans living on tribal land to purchase guns.

Under current law, tribal IDs are not considered valid forms of identification for buying guns. The Tribal Firearm Access Act would allow members of federally recognized tribes to use their tribal ID cards to purchase guns from federally recognized dealers.

“Classifying tribal IDs as an invalid form of identification for the purchase of firearms limits tribal sovereignty and tribal members’ ability to obtain a firearm,” Johnson said in a written statement. “A foreign passport is accepted as a valid form of identification — a tribal ID should be no different. My bill corrects this oversight, ensuring Second Amendment rights for tribal members.”

Democratic Representative Mary Peltola, the first Alaskan Native elected to Congress, is co-sponsoring the bill. She says firearms are essential to subsistence and self-defense in her state.

Republican Senator Markwayne Mullin of Oklahoma, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, introduced a companion bill Wednesday in the U.S. Senate.

Read more:

Forest Service to OK Arizona land swap, give go-ahead to copper mine

The U.S. Forest Service is set to approve a land swap between the U.S. government and Resolution Copper, a joint venture owned by multinational mining giants Rio Tinto and BHP.

That would allow the company to build a copper mine on land in Oak Flat, Arizona, that has historic and spiritual significance to the San Carlos Apache and other tribes in the state.

With an estimated 40 billion pounds of copper at the site, Resolution Copper says it is "committed to preserving Native American cultural heritage while developing partnerships and bringing lasting benefits to the entire region."

Congress approved the land transfer in 2014 in exchange for 6,000 acres elsewhere.

Wendsler Nosie Sr., former chairman and councilman of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, discusses Apache opposition to the mine in the video below:

Read more:

Indigenous Artists Help Skateboarding Earn Stamp of Approval

Years ago, skateboarding was branded as a hobby for rebels or stoners in city streets, schoolyards and back alleys. Those days are long gone.

Skateboarding, which has Native Hawaiian roots connected to surfing, no longer is on the fringes. It became an Olympic sport in 2020. There are numerous amateur and professional skateboarding competitions in the U.S. And on Friday, the U.S. Postal Service issued stamps that laud the sport — and what Indigenous groups have brought to the skating culture.

Di'Orr Greenwood, 27, an artist born and raised on the Navajo Nation in Arizona whose work is featured on the new stamps, says it's a long way from when she was a kid and people always kicked her out of certain spots just for skating.

"Now it's like being accepted on a global scale," Greenwood said. "There's so many skateboarders I know that are extremely proud of it."

The postal agency debuted the "Art of the Skateboard" stamps at a Phoenix skate park. The stamps feature skateboard artists from around the country, including Greenwood and Crystal Worl, who is Tlingit Athabascan. William James Taylor Jr., an artist from Virginia, and Federico "MasPaz" Frum, a Colombian-born muralist in Washington, D.C., round out the quartet of featured artists.

The stamps underscore the prevalence of skateboarding, especially in Indian Country where the demand for skate parks is growing.

The artists see the stamp as a small canvas, a functional art piece that will be seen across the U.S. and beyond.

"Maybe I'll get a letter in the mail that someone sent me with my stamp on it," said Worl, 35, who lives in Juneau, Alaska. "I think that's when it will really hit home with the excitement of that."

Antonio Alcalá, USPS art director, led the search for artists to paint skate decks for the project. After settling on a final design, each artist received a skateboard from Alcalá to work on. He then photographed the maple skate decks and incorporated them into an illustration of a young person holding up a skateboard for display. The person is seen in muted colors to draw attention to the skate deck.

Alcalá used social media to seek out artists who, besides being talented, were knowledgeable about skateboarding culture. Worl was already on his radar because her brother, Rico, designed the Raven Story stamp in 2021, which honored a central figure in Indigenous stories along the coast in the Pacific Northwest.

The Worl siblings run an online shop called Trickster Company with fashions, home goods and other merchandise with Indigenous and modern twists. For her skate deck, Crystal Worl paid homage to her clan and her love of the water with a Sockeye salmon against a blue and indigo background.

She was careful about choosing what to highlight.

"There are certain designs, patterns and stories that belong to certain clans and you have to have permission even as an Indigenous person to share certain stories or designs," Worl said.

The only times Navajo culture has been featured in stamps is with rugs or necklaces. Greenwood, who tried out for the U.S. Women's Olympic skateboarding team, knew immediately she wanted to incorporate her heritage in a modern way. Her nods to the Navajo culture include a turquoise inlay and a depiction of eagle feathers, which are used to give blessings.

"I was born and raised with my great-grandmother, who looked at a stamp kind of like how a young kid would look at an iPhone 13," Greenwood said. "She entrusted every important news and every important document and everything to a stamp to send it and trust that it got there."

Skateboarding has become a staple across Indian Country. A skate park opened in August on the Hopi reservation. Skateboarders on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in eastern Arizona recently got funding for one from pro skateboarder Tony Hawk's nonprofit, The Skatepark Project. Youth-organized competitions take place on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Dustinn Craig, a White Mountain Apache filmmaker and "lifer" skateboarder in Arizona, has made documentaries and short films on the sport. The 47-year-old remembers how skateboarding was seen as dorky and anti-establishment when he was a kid hiding "a useless wooden toy" in his locker. At the same time, Craig credits skateboarding culture as "my arts and humanities education."

So he is wary of the mainstream's embrace, as well as the sometimes clique-ish nature, of today's skateboarding world.

"For those of us who have been in it for a very long time, it's kind of insulting because I think a lot of the popularity has been due to the proliferation of access to the visuals of the youth culture skateboarding through the internet and social media," Craig said. "So, I feel like it really sort of trivializes and sort of robs Native youth of authenticity of the older skateboard culture that I was raised on."

He acknowledges that he may come off as the "grumpy old man" to younger Indigenous skateboarders who are open to collaborating with outsiders.

The four skateboards designed by the artists will eventually be transferred to the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, said Jonathan Castillo, USPS spokesperson.

The stamps, which will have a printing of 18 million, are available at post offices and on the USPS website. For the artists, being part of a project that feels low-tech in this age of social media is exciting.

"It's like the physical thing is special because you go out of your way to go to the post office, buy the stamps and write something," Worl said.

Tourists Hoping to See Arizona Falls Forced Out by Flooding

Shannon Castellano and Travis Methvin should have spent this weekend seeing world-famous waterfalls on the Havasupai Tribe Reservation in the southwestern U.S. state of Arizona.

Instead, the two friends from San Diego spent Friday night along with 40 other hikers camped out on a helipad. But sleep was elusive because tribal members warned that an emergency services helicopter could potentially land anytime during the night.

"Yeah, so we didn't really sleep," Castellano said Saturday while driving to a hotel in Sedona. "I just kept one eye open really and one ear open ... You just do not expect any of that to happen. So, I think I'm still in shock that I'm not even there right now."

Tourists hoping to reach the breathtaking waterfalls on the reservation instead went through harrowing flood evacuations.

The official Havasupai Tribe Tourism Facebook page reported Friday that flooding had washed away a bridge to the campground. An unknown number of campers were evacuated to Supai Village, with some being rescued by helicopter.

The campground is in a lower-lying area than the village of Supai. Some hikers had to camp in the village. Others who weren't able to get to the village because of high water were forced to camp overnight on a trail.

But floodwaters were starting to recede as of Saturday morning, according to the tribe's Facebook post.

Visitors with the proper permits will be allowed to hike to the village and campground. They will be met with tribal guides, who will help them navigate around creek waters on a back trail to get to the campground.

Tourists will not be permitted to take pictures. The back trail goes past sites considered sacred by the tribe.

Meanwhile, the tribe said in its statement that it has "all hands on deck" to build a temporary bridge to the campground.

Abbie Fink, a spokesperson for the tribe, referred to the tribe's Facebook page when reached for comment Saturday.

Methvin and Castellano decided to leave by helicopter Saturday rather than navigate muddy trails with a guide. Despite losing money on a pre-paid, three-day stay, Methvin says they can still try to salvage their trip. Having only received permits last month, he feels especially sad for hikers they met with reservations from 2020.

"They waited three years to get there," Methvin said. "At least we have the ability to go do something else versus having that whole weekend ruined."

From Supai to Sedona, several areas of northern Arizona have been slammed this week by storms. The resulting snow combined with snowmelt at higher elevations has wreaked havoc on highways, access roads and even city streets.

The flooding of the Havasupai campground comes as the tribe reopened access last month to its reservation and various majestic blue-green waterfalls — for the first time since March 2020. The tribe opted to close to protect its members from the coronavirus. Officials then decided to extend the closure through last year's tourism season.

At the beginning of this year, President Joe Biden approved a disaster declaration initiated by the Havasupai Tribe, freeing up funds for flood damage sustained in October. Flooding at that time had destroyed several bridges and left downed trees on trails necessary for tourists and transportation of goods into Supai Village.

Permits to visit are highly coveted. Pre-pandemic, the tribe received an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 visitors per year to its reservation deep in a gorge west of Grand Canyon National Park. The area is reachable only by foot or helicopter, or by riding a horse or mule. Visitors can either camp or stay in a lodge.

Castellano is already planning to try to get a permit again later this year if there are cancellations. "We just want to see i in all its glory, not muddy falls," she said.

Native American News Roundup March 12-18, 2023

Here is a summary of some of the stories making headlines this week:

Native Americans debate Indigenous land acknowledgements: ‘In one ear and out the other?’

Land acknowledgements are formal statements that recognize Indigenous custodianship of geographic areas on which institutions stand or events take place.

Evolving from Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, land acknowledgments are becoming increasingly common at U.S. universities and sporting events.

But are they effective?

Cutcha Risling Baldy, a member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe and an associate professor of Native American Studies at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, tells NPR they are a good start but believes institutions should go on to “assist Indigenous peoples in uplifting and upholding their sovereignty and self-determination.”

Kevin Gover, a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma and undersecretary for museums and culture at the Smithsonian Institution, worries that if land acknowledgements become “routine, or worse yet... strictly performative,” they will lose their meaning.

Read more:

Lac du Flambeau tribe in Wisconsin lifts weekslong road blockades

The Lac du Flambeau Tribe has agreed with the town of Lac du Flambeau to reopen four roads on the northern Wisconsin reservation that it barricaded in late January. The deal is temporary as parties to the dispute have 90 days to work out a longer-term solution.

The roads were built in the 1960s on tribal land and are the only access route for non-Native residents in more than 60 households that are scattered among reservation land.

Easements to use the roads expired in 2013, and negotiations to extend them have so far failed. The Lac du Flambeau Tribal Council says it is owed $20 million for trespassing on its land since the easements expired.

Read more:

Cayuga Nation locked in power struggle

The New York Times this week reports on a leadership dispute inside the Cayuga Nation in New York, which one observer has called “one of the more volatile in Indian Country today.”

The feud pits Cayuga Chiefs and Clan Mothers, the traditional government of the Nation, against Clint Halftown, the Cayuga Nation representative federally recognized by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Traditionalists say Halftown has no authority under their system of governance outlined in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy Great Law of Peace because they view his council as an entity of the federal government.

Halftown says more than 60% of Cayuga Nation citizens signed a statement of support affirming the current Nation Council and delegitimizing the “Unity Council.” He says Cayuga-owned buildings destroyed by National Council bulldozers were illegal.

Read more:

NAGPRA compliance: Lots of promises but not enough follow-through

ProPublica reports that its ongoing “Repatriation Project” has sparked “waves” of promises by institutions to redouble efforts to repatriate thousands of Native American ancestral remains in their collections.

But seeing is believing, according to Shannon O’Loughlin, a Choctaw Nation citizen and chief executive of the Association on American Indian Affairs. She told ProPublica that museums and universities have interpreted the law in ways that have allowed them to resist returning remains and stay out of the limelight for years.

“But, hey, they’re saying it in the public, so we’re gonna hold them to it,” she said.

Read more:

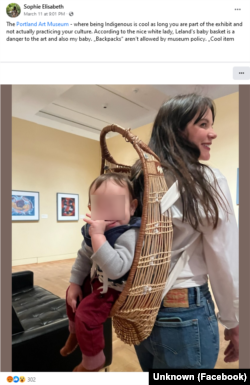

Portland Museum apologizes to Native mother

The Portland Art Museum in Oregon has apologized after one of its employees asked a Kayuk mother to remove the traditional woven basket in which she carried her baby.

Sophie Neuner posted about the March 11 incident on her Facebook page:

“According to the nice white lady, [my child’s] baby basket is a danger to the art and also my baby. … Racism is alive and well in these walls."

The museum issued an apology on Facebook and Twitter Monday and has since amended its policy to read: “We kindly request that bags, backpacks, or items larger than 11″ x 17″ x 6″ be left outside the Museum. Babies in carriers are permitted. Other bags should be carried at your side or in front, and not worn on one’s back.”

VOA checked visitors’ guides for several major art museums across the U.S. and found that bans on the wearing of backpacks are common because they can damage works on display. These include the Smithsonian Institutions in Washington, D.C. The National Museum of the American Indian, a Smithsonian entity, advises visitors, "Suitcases, large umbrellas, and large backpacks are not allowed in the galleries."

Feds Want Justices to End Navajo Fight for Colorado River Water

States that rely on water from the over-tapped Colorado River want the U.S. Supreme Court to block a lawsuit from the Navajo Nation that could upend how water is shared in the Western U.S.

The tribe doesn't have enough water and says that the federal government is at fault. Roughly a third of residents on the vast Navajo Nation don't have running water in their homes.

More than 150 years ago, the U.S. government and the tribe signed treaties that promised the tribe a "permanent home" — a promise the Navajo Nation says includes a sufficient supply of water. The tribe says the government broke its promise to ensure the tribe has enough water and that people are suffering as a result.

The federal government disputes that claim. And states, such as Arizona, California and Nevada, argue that more water for the Navajo Nation would cut into already scarce supplies for cities, agriculture and business growth.

The high court will hold oral arguments Monday in a case with critical implications for how water from the drought-stricken Colorado River is shared and the extent of the U.S. government's obligations to Native American tribes.

A win for the Navajo Nation won't directly result in more water for the roughly 175,000 people who live on the largest reservation in the U.S. But it's a piece of what has been a multi-faceted approach over decades to obtain a basic need.

Tina Becenti, a mother of five, made two or three short trips a day to her mom's house or a public water spot to haul water back home, filling several five-gallon buckets and liter-sized pickle jars. They filled slowly, sapping hours from her day. Her sons would sometimes help lift the heavy containers into her Nissan SUV that she'd drive carefully back home to avoid spills.

"Every drop really matters," Becenti said.

That water had to be heated then poured into a tub to bathe her young twin girls. Becenti's mother had running water, so her three older children would sometimes go there to shower. After a couple of years, Becenti finally got a large tank installed by the nonprofit DigDeep so she could use her sink.

DigDeep, which filed a legal brief in support of the Navajo Nation's case, has worked to help tribal members gain access to water as larger water-rights claims are pressed.

Extending water lines to the sparsely populated sections of the 69,000-square-kilometer reservation that spans three states is difficult and costly. But tribal officials say additional water supplies would help ease the burden and create equity.

"You drive to Flagstaff, you drive to Albuquerque, you drive to Phoenix, there is water everywhere, everything is green, everything is watered up," said Rex Kontz, deputy general manager of the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority. "You don't see that on Navajo."

The tribe primarily relies on groundwater to serve homes and businesses.

For decades, the Navajo Nation has fought for access to surface water, including the Colorado River and its tributaries, that it can pipe to more remote locations for homes, businesses and government offices.

It's a legal fight that resonates with tribes across the U.S., said Dylan Hedden-Nicely, the director of the Native American Law Program at the University of Idaho and an attorney representing tribal organizations that filed a brief in support of the Navajo Nation.

The Navajo Nation has reached settlements for water from the San Juan River in New Mexico and Utah. Both of those settlements draw from the Colorado River's Upper Basin.

The tribe has yet to reach agreement with Arizona and the federal government for water rights from the Colorado River in the Lower Basin that includes the states of California, Arizona and Nevada. It also has sought water from a tributary, the Little Colorado River, another major legal dispute that's playing out separately.

In the U.S Supreme Court case, the Navajo Nation wants the U.S. Department of the Interior to account for the tribe's needs in Arizona and come up with a plan to meet those needs.

A federal appeals court ruled the Navajo Nation's lawsuit could move forward, overturning a decision from a lower court.

Attorneys for the Navajo Nation base their claims on two treaties the tribe and the U.S. signed in 1849 and 1868. The latter allowed Navajos to return to their ancestral homelands in the Four Corners region after being forcibly marched to a desolate tract in eastern New Mexico.

The Navajo Nation wants the Supreme Court to find that those treaties guaranteed them enough water to sustain their homeland. And the tribe wants a chance to make its case before a lower federal court.

The federal government says it has helped the tribe get water from the Colorado River's tributaries, but no treaty or law forces officials to address the tribe's general water needs. The Interior Department declined to comment on the pending case.

"We absolutely think they're entitled to water, but we don't think the lower Colorado River is the source," said Rita Maguire, the attorney representing states in the Lower Basin who oppose the tribe's claims.

If the Supreme Court sides with the Navajo Nation, other tribes might make similar demands, Maguire said.

Arizona, Nevada and California contend the Navajo Nation is making an end run around another Supreme Court case that divvied up water in the Colorado River's Lower Basin.

"The first question in front of the court now is: why is the lower court dealing with the issue at all?" said Grant Christensen, a federal Indian law expert and professor at Stetson University.

Even if the justices side with the Navajo Nation, the tribe wouldn't immediately get water. The case would go back to the U.S. District Court in Arizona, and rights to more water still could be years, if not, decades away. The Navajo Nation also could reach a settlement with Arizona and the federal government for rights to water from the Colorado River and funding to deliver it to tribal communities.

Tribal water rights often are tied to the date a reservation was established, which would give the Navajo Nation one of the highest priority rights to Colorado River water and could force conservation on others, said Hedden-Nicely of the University of Idaho.

Given the likelihood of a long road ahead, Kontz of the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority says many older Navajo won't live to see running water in their homes.

Becenti, the 42-year-old mother of five, remembers shedding tears of joy when running water finally was installed in her house and her family could use a flushable indoor toilet.

It was a relief to "go to the facility without having to worry about bugs, lizards, snakes," she said.