Two years after sexual misconduct allegations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein launched the #MeToo movement, there are signs of a possible backlash.

Surveys show an increasing number of male managers are uncomfortable working closely with women since a string of prominent men lost their jobs after being accused of sexual misconduct.

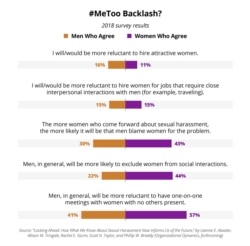

A 2018 survey shows 41% of men say they’re more reluctant to have a one-on-one meeting alone with a woman. And more than one-in-five men say they’re more inclined to exclude women from social interactions like meeting for drinks after work.

A study released earlier this year suggests even greater concern among senior men in the workplace, with 60% of male managers saying they’re uncomfortable mentoring, socializing or having one-on-one meetings with women.

Those findings don’t exactly surprise New York City consultant Davia Temin, who runs a crisis management firm and maintains an index of high-profile accusations of sexual harassment and abuse.

“Yeah. I think there is a #MeToo backlash. I don't think it's serious. I don't think it's lasting and I think #MeToo is here forever,” Temin says. “This is incredibly uncomfortable and the mores of our culture are really changing right now in real time and, of course, change is uncomfortable.”

The current number of accusations in the Temin Index is 1474. Accusations have whittled down from a monthly high of 143 in October of 2018, to about a dozen or so monthly more recently. Temin believes that’s because companies are getting smarter about handling harassment issues internally to keep them from going public.

“I think they're scared enough by this movement that even if they don't, in their heart of hearts, believe in this, they're going to pay lip service to it and they're going to appear to take it seriously,” Temin says.

WATCH THE VIDEO:

Columbia University law Professor Olatunde Johnson, who writes about modern civil rights legislation and innovative ways to address discrimination and inequality, sees #MeToo as a strong force for change.

“I think one of the most powerful things is that it's really brought attention to the issue of sexual harassment to sexual assault and it has provided a way for women to collectivize their stories,” Johnson says. “A lot of times people don't believe people in isolation, but when you hear repeated stories that's when you begin to think these are systemic problems that we need to deal with. And that's powerful.”

According to the National Women’s Law Center, 15 states — including New York, California, Arizona and Illinois — have passed new laws aimed at protecting employees from sexual harassment and gendered discimination since October 2017, when the #MeToo movement catapulted into the public consciousness.

But those changes don’t necessarily help low-paid hourly workers who are unfamiliar with the legal system.

"They don't know their rights. They work in workplaces where they don't have a human resources officer who's doing diversity training,” Johnson says. “So how are you going to reach low-wage workers, independent contractors, people who are working in the agricultural industry, in domestic house? And so some states have made efforts in that, but you're not seeing that across the board.

Both Johnson and Temin participated in a recent #MeToo-related panel discussion at Columbia University in New York. They were joined by writer and editor Shelly Oria, who compiled a collection of #MeToo-related writings into a book entitled, "Indelible in the Hippocampus."

“The internet is very strong and powerful,” Oria says. “And yet I do find that in most ways it is preparatory in nature. It prepares us for action, that if it doesn't then translate to the physical world, nothing really changes. For laws to change, for the reality in the workplace to change, for women's pay to change, for women's experiences in the street to change, changes have to happen in the physical world. And that is one of the ways that I think literature can play a part, is that a book lives in the physical world.”

Retired attorney Robert Ouimette, who attended the discussion, says #MeToo helped enlighten him as to why some women might have had difficulty maintaining long-term law careers.

“I think probably it's a good thing that people are thinking about who they're alone with and who they're not alone with and under what circumstances they're alone with them,” he says. “And I, actually, am quite amazed by some of the things I hear about you know the people being invited or women being expected to go to hotel rooms and all that.”

While it’s too early to assess the long-term impact of Me-Too, Temin says the movement is like opening Pandora's box and there's no closing it.