Thelda Williams was already in her 40s when she was first elected to the city council in Phoenix, Arizona, but that didn’t stop people from assuming she wasn’t up to the task. The Arizona Republican believes people underestimated her because she is a woman.

“Staff, in the very, very beginning, really treated me like, ‘Well, you probably don't understand. This is probably too overwhelming. There are too many subjects,’” she recalls. “And, you know, you prove them wrong.”

Decades later, Williams remains on the city council, having served as interim mayor three times, most recently during a stint that ended in March. One of the arenas in which Williams still believes she isn’t treated equally is when it comes to how the media cover her.

“You know, I just don't get the same respect. I mean, they talk about everything from what shoes I wear, to what color my hair is, to what my age is,” she says. “You don't see that with the men. ... What really irritates me is when it's a woman who's written the article.”

The undermining of women in politics is not new. Stereotypes and double standards continue to exist for female politicians, says Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

“And it starts with things as basic and as simple as being scrutinized for their physical appearance, what they wear, how their hair looks, the way in which they speak,” Walsh says.

“During the 2016 presidential election, we heard comments that Hillary Clinton didn't smile enough. We never heard that about Bernie Sanders, and heaven knows he is not somebody who grins. He's pretty grumpy, and so is, for that matter, Donald Trump.”

Women are also criticized for being shrill when they speak forcefully. Media focus on details not related to the issues can hurt women electorally.

“If the media is not focusing on the content of what women are talking about, but much more on their presentation, their style, their appearance, it diminishes them as serious candidates,” Walsh says.

“And this becomes even more of a challenge for women who are running for office, because women are not assumed — in the same way that men are assumed to be — qualified and capable and able to hold these offices. So, they have to prove themselves in ways that male candidates do not.”

A record number of women are running for president in 2020, and how the press covers them could impact their political fortunes.

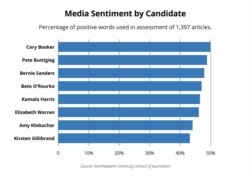

In Massachusetts in March, Northeastern University’s School of Journalism examined almost 1,400 articles about the 2020 presidential election and found that the female candidates were consistently described more negatively than their male counterparts.

The female candidate with the fewest positive words written about her, Kirsten Gillibrand, has already quit the race.

Walsh says female candidates have to navigate the presidential debates differently than men because a man who interrupts or asserts himself is not written up in quite the same way as a woman who does the same thing.

She’s also concerned about the recurring question of electability.

“There is this assumption that somehow after 2016, the Democrats need to ‘play it safe’ right now and not take a risk on a woman candidate, that they have to win,” she says. “I assume 'traditional' is white and male and probably over 60 years old.”

Williams isn’t holding out hope that media coverage will one day focus solely on the issues and not her appearance, delivery style or age.

“I mean, it doesn't seem like they're ever going to change,” she says. “I think they expect me to behave nicer, be a little gentler. The men can get away with saying just about anything — it can be swear words — whereas a woman, you can't. We’re expected, I think, you have to behave.”

In her experience, there are very specific losses for society when women are not at the decision-making table.

“I think right off the bat, compassion. And not only for people — kids, seniors, families, animals. I think that's all missing if it's just left up to men,” Williams says. “Morals would be so much different if there were no women politicians. I think they bring much more detail and depth to almost every subject.”

Democrat Erin Schrode, who ultimately lost her 2016 congressional bid in her California district, faced an onslaught of misogynistic attacks and physical threats from nontraditional media. The online campaign against her was orchestrated by a popular neo-Nazi website.

“Insinuating that I had, or would, perform sexual acts to advance my standing in the political world,” she says, recalling the online attacks against her. “That I wouldn't have my job if I weren’t pretty. And on the flip side, that I was too hideous to even merit a vote.”

Despite the harassment she endured, Schrode agrees with Williams that more women are needed in public office and hasn’t ruled out a future run for herself.

“We need that perspective, that judgment, that level headedness, that experience the same way that we need all voices represented in Congress,” she says.

“Women are communicators. Women are fighters. Women are mothers. Women are forces to be reckoned with. And our place is wherever we want it to be, and that most certainly includes the halls of Congress."