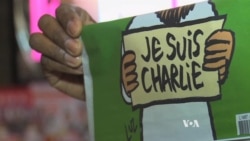

Last week’s killings in Paris were carried out by militants professing to avenge the Prophet Muhammad. When they attacked the office of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and a kosher grocery store, they slaughtered iconoclastic cartoonists and Jews shopping for kosher food, shot dead a Muslim policeman, and unleashed an emotional debate about blasphemy, bigotry and the limits of free speech.

France, like other European countries, has laws against anti-Semitism and xenophobia. And many majority Muslim countries outlaw depictions of the Prophet Muhammad and criticism of Islam.

The United States has no such laws. Most Muslim and Jewish civil rights organizations in America argue that such measures don’t work to prevent racial or religious attacks.

“We think, as a rule, expression is something that is enriching society, even when it is ugly expressions,” said David Friedman of the Anti-Defamation League.

As ADL’s law enforcement coordinator, he works with American police departments to help them identify when anti-Semitism is a motivating factor in so-called hate crimes.

Friedman says that just because people may have the right to offend Muslims, that does not mean they should.

“In a world in which people’s sensitivities are very great, rubbing salt in their wounds or rubbing their nose in that, ‘We can do this,’ is not necessarily helping us to be a more kind, compassionate, understanding world,” he said.

In 2010, protests erupted in the U.S. against the proposed construction of a mosque near the site of the September 11, 2001, attacks, and also over a Florida pastor’s threat to burn a copy of the Quran, Islam's holy book. In response, a group of multifaith clergy in Washington formed a group called Shoulder to Shoulder, aimed at stopping Islamophobia.

Haris Tarin of the Muslim Public Affairs Council says Shoulder to Shoulder and other campaigns have convinced American journalists that caricatures of Muhammad, like those that have appeared in Charlie Hebdo as well as the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten a decade ago, were offensive.

“Although we do not have any laws that prohibit newspapers from reprinting the cartoons, we have seen in the past that when the cartoons were published, American newspapers did not publish those cartoons,” he said.

By contrast, Tarin said, outright bans on insulting Islam, as exist in many majority Muslim countries, are rarely just.

“In places like Pakistan, in Indonesia, in Egypt, when we have government which has laws against blasphemy, it is used for political reasons, generally,” he said. “It is used against minority groups; it is used against people who do not have the power and who are not the majority.”