Dozens of governments around the world, most notably in majority-Muslim nations, are turning to anti-blasphemy laws to aggressively punish alleged transgressions, especially against Islam.

And while in the past blasphemy charges were most often brought against people for something they said in public, these days governments are turning their attention to what people say and do while online, analysts say.

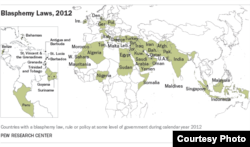

According to Peter Henne, an analyst with the Pew Research Center, 22 percent of governments have some form of anti-blasphemy law on the books. No region is immune: anti-blasphemy laws can be found in at least one nation on every continent, he said.

“Seventy percent of the nations located in the Middle East or North Africa have anti-blasphemy laws,” he said. “Fourteen of the 20 nations in that region criminalize blasphemy, but again it’s not unique to this area.”

Among the nations that most aggressively pursue blasphemy cases, he said, are Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and he says Indonesia.

While the Pew study didn’t specifically track the punishments imposed in each nation, in general the sentences vary widely, from forms of house arrest to life in prison or death.

Saudi case

Recently, a 30-year-old blogger and Saudi citizen, Raif Badawi, founded the “Free Saudi Liberals” website to foster discussion about religion and Saudi religious figures.

In 2012, he was arrested for insulting Islam on his blog and committing apostasy – a charge that was later dropped. He was convicted on the first charge and lost his appeal and is now serving a sentence of 10 years in prison and 1,000 lashes, to be meted out 50 each week for 20 weeks.

His first flogging on January 9th reportedly lasted approximately 15 minutes.

U.S. State Department spokesperson Jen Psaki said Badawi’s punishment is “inhumane” and has called on Riyadh to cancel his punishment.

So far the Saudi government, which has denounced the attack on the staffers of the French publication Charlie Hebdo over the issue of blasphemy, has shown no signs of changing course on Badawi.

Increasingly, Badawi’s story is becoming more common across large portions of the Middle East and North Africa.

In 2013 Kuwaiti blogger Hamad al-Naqi was found guilty of insulting the Prophet Muhammad while making comments on Twitter, and sentenced to ten years in prison.

In Mauritania, a blogger named Mohamed Cheikh Ould Mohamed was sentenced to death after being found guilty of insulting Islam and apostasy, or renouncing Islam, relating to an article he published in 2013.

In Pakistan alone, more than 30 people have been sentenced to death or life in prison for allegedly committing blasphemy, either online or in person.

Around the world it’s estimated that at least 50 people are currently in prison or facing death sentences for violating these laws. And just this week, India's solicitor general, Tushar Mehta, argued before that nation's Supreme Court that "outrageous and offensive" material targeting religion online should be blocked.

Online scrutiny

And as Internet use spreads, so too do prosecutions based on people’s online activities.

“It’s easier to scrutinize what people are doing online,” said Philip Luther, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at Amnesty International. “The web has made it easier for governments to prosecute people,” in part, he says, because online comments and social media posts live on forever.

Amnesty International has called Badawi’s conviction and sentence in Saudi Arabia “a vicious act of cruelty” and, like the United States, is urging the government there to stop his punishment.

“Our position is quite clear; we consider him to be a prisoner of conscience,” Luther told VOA. “He’s done nothing more than express his views peacefully, and it’s unquestionable he should be released immediately and his sentence quashed.”

Luther points to several nations as leading offenders, including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Pakistan, Iran and Indonesia.

“Indonesia is an interesting case,” he said. “Over the past decade there’s been a real increase in the use of a range of blasphemy laws there.

"We’ve documented more than 100 individuals who served in prison during the administration of former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, compared to just a handful in the preceding decade, so there’s clearly been a surge in prosecutions there,” he said.

In a challenge to the law, Indonesia’s Constitutional Court in 2010 ruled 8-to-1 that the laws would remain, stating in the majority opinion that the blasphemy law “…is still needed to maintain public order among religious groups.”

While only some of those 100 cases in Indonesia stem from Internet use, analyst Luther said there’s a growing trend among prosecutors to use the web and social media to gather evidence for possible charges.

“An Iranian man was sentenced to death on the thirtieth of August last year for Facebook posts insulting the prophet of Islam,” he said. “In Egypt, both Muslims and Christians have been prosecuted for showing contempt for religion online.

"So the fact that it’s easier to scrutinize what people are doing online has made it easier for governments like these to prosecute people,” he said.

While the United Nations has repeatedly called freedom of expression and religion to be universal rights, the United Nations General Assembly is considering a resolution that some fear might chip away at that.

Pushed by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, resolution 16/18 aims to combat “…intolerance, negative stereotyping and stigmatization of, and discrimination, incitement to violence, and violence against persons based on religion or belief.”

Protecting People vs. Protecting Ideas

“Blasphemy laws violate both internationally protected rights of freedom and expression, and they should be repealed,” said Elizabeth Cassidy, deputy director for policy research at the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, an independent federal government organization.

“They completely turn the human rights regime on its head,” she said. “Human rights are about protecting human beings, not protecting ideas. If you’re protecting ideas, you have to face the question of deciding what ideas are acceptable and what aren’t.”

Cassidy said the online world over the past few years is proving to be a source for many blasphemy allegations, adding that the trend accelerated following the Arab Spring and the rapid growth of social media use around the world.

“I think we saw people willing to say things online that they weren’t willing to say before, so that’s been a worry,” she said. “And we’re seeing more moves against people who say they are atheist or are questioning the existence of God.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story suggested the USCIRF views blasphemy laws and UNHRC Resolution 16/18 similiarly, which is incorrect. The text has been corrected.