Among many cultures in Africa, traditions protect the health of women and children, and the family. Some ethnic groups encourage women to breastfeed their infants for over a year, thus encouraging the safe practice of greater spacing between pregnancies.

And in Sierra Leone, a Krio saying, “Bad children may not be thrown into the bush” (“Bush noh de foh trwoe bad pikin”) guarantees that children will not be disowned by the family, no matter how difficult they are.

But other traditions and practices are harmful, say many health care professionals, and contribute to the country’s high rates of maternal and child mortality.

Lack of power

Dr. Ibrahim Thorlie, the consultant obstetrician and gynecologist at the Princess Christian Maternity Hospital in Freetown, says some traditions may prevent women from receiving needed medical treatment during a pregnancy.

Thorlie sits behind a large wooden desk in his office at the hospital, in a white doctor’s coat and a stethoscope around his neck. The echo of crying infants drifts through the half-open door.

He says he has found that women often have little control over whether they receive medical or hospital care during pregnancy.

“Tradition says before you go anywhere, the husband must approve. I think that is [also a question of finances], because the husband in the traditional African home provides the funds. So if you want to go and if you don’t have funds,” he says, “you can’t go.”

Studies by UNICEF and the World Health Organization confirm those views.

A survey by the two UN agencies shows that most women in rural areas are prevented from receiving pre-natal care from qualified providers, in part because tradition bars them from interacting with anyone other than their spouse or female members of their family while pregnant.

Some women, especially those who are circumcised, will refuse to allow themselves to be examined by a male doctor or by a nurse who is not circumcised.

Little control over family size, health care

Tradition also impacts the number of children a woman has and the frequency of births. Women may have little say in these decisions, because they are typically made by male head of families.

Some ethnic groups favor boys as a way to perpetuate the family name. Sons are also usually responsible for the care of aging parents and for performing the parent’s burial rites, says the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices, an international network of non-governmental organizations working to improve health maternal and child care.

Many families have large numbers of children in the belief that some will not live to adulthood. UNICEF figures show that half of the nearly nine million children under five who die each year are in sub-Saharan Africa.

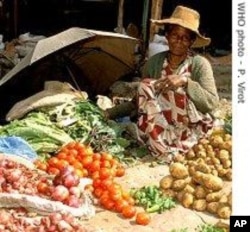

Culture and diet

Tradition may affect the health of a woman in other ways. They may be among the last to eat nutritious food at the family table. In some ethnic groups, the woman is discouraged from eating meat and eggs during pregnancy, says Brima Abdulai Sheriff, director of Amnesty International in Sierra Leone.

“If she prepares a chicken,” he says, “all she can eat is wings, feet, the neck and the head. The fleshy and nutritious part is given to the husband. This is a show of love to your husband. In some communities, [it is believed] if you [give a pregnant woman] meat, she will give birth to a child who is a witch.”

He says pregnant women may harm their unborn child by fasting, which he says can deprive the fetus of needed nutrients.

Stifling debate

Traditions may also discourage open debate about maternal care.

Women are not to complain, says Dr. Peter Sikana, describing the private nature of pregnancy and childbirth. Sikana is a reproductive health and emergency obstetric care technical advisor for the UN Population Fund in Freetown.

“There are some tribes where a woman is left alone to go through the process of labor, and she’s not supposed to make noise even if she’s in pain; it’s believed to be [a sign of] strength that [tends to work] against quality care for a woman.” Going to a clinic, he says, is a sign of moral failure.

Sometimes, traditional beliefs in Sierra Leone blame women for difficult pregnancies.

One saying equates women to a calabash. When a woman dies during childbirth, the calabash is said to be “broken,” and shame is brought on the community. In some parts of the country, complications during delivery are attributed to infidelity, according to a recent Amnesty International report, Out of Reach: The Cost of Maternal Health in Sierra Leone.

“Often, time and energy are wasted in trying to obtain a confession instead of ensuring that the woman, who is in agony as the baby fails to emerge, has access to the necessary obstetric care,” says the study.

Maternal and child health may also be influenced by spiritual values, says Dr. Sikana.

“There may be religious influences,” he says, “where people believe whatever God gives you is what you have. Whatever happens is attributed to God – you must have a certain [predetermined] number of children, so people don’t go for family planning.” The life or death of the mother and infant may be God’s will, with little attention paid to the support of health care workers.

Not all cultural practices are harmful to mothers and infants, says Dr. Donald Bash-Taki, a prominent private medical practitioner at one of Sierra Leone’s oldest medical institutions, Connaught Hospital in the busy center of Freetown.

The answer, he says, is to use medical providers who share the same cultural norms as their patients.

“There are some ethnic groups [that], because of their own beliefs, do not like women to [go to] public [care centers] to have deliveries,” he says. “But (if) you use [health care workers from] those ethnic groups, it can overcome that problem to see that, yes, all care and delivery occurs within the community. So again, if you work within the community, give more community ownership [of] these programs, and then it will work.”

Community leadership

Powerful traditional figures, such as local chiefs, can play a big role in ensuring that superstitions and cultural practices do not stand in the way of maternal and child health, says Mohammed Mansere, a supervisor of traditional birth attendants.

“We should use the influence of the paramount chiefs, the section chiefs, to give them a mandate that whenever a woman is pregnant, she should immediately go to the health facility, instead of wasting time.”

He also says medical information should be translated into local languages for the mother and health care workers.

Women’s rights activists say one key to reducing the influence of harmful practices lies in enhancing women’s political clout. Many are working with local women’s groups to help elect women to office.

They say a stronger voice of women in government and within families will help create a new tradition of better health for pregnant women and their babies in Sierra Leone.

This is part 7 of our 15 part series, A Healthy Start: On the Frontlines Maternal and Infant Care in Africa