Years of civil war all but destroyed Sierra Leone’s healthcare infrastructure. Even now that peace has returned to the country, the legacy of inadequate health care continues.

Among those hardest hit are pregnant women, who often can’t get access to emergency obstetric care. As a result, thousands each year suffer from injuries during childbirth, including fistula, a tear in the tissue of the bladder or rectum caused by obstructed birth. Unless repaired, urine and other fluids are passed uncontrollably, leading to discomfort and social ostracism.

Brima Abdulai Sheriff, the director of Amnesty International in Freetown, knows the situation well. His late aunt was affected by the condition, which he says took a considerable psychological toll.

“It was a discomfort for her. In (her) last days…it was difficult for her to be in the company of a lot of people. She would stay away and go to the street to clean herself. She had a bad smell, [which she masked with] perfume and other scents. Children would refuse to go to her room.”

Fistula and other complications during delivery are common in girls who marry early and become pregnant before their pelvis is fully developed.

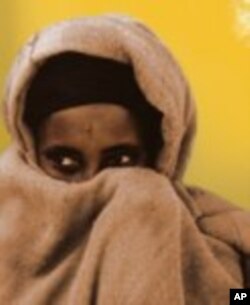

Health care professionals say women with fistula are often very young, live in rural areas and are illiterate. They are usually pressured by family and tradition to get married and do not understand the impact of early marriage and childbirth on their maturing bodies. The Women of Africa Fund estimates that every year in Sierra Leone there are 5,000 new cases of fistula.

Funding and resources

<!-- IMAGE -->

Dr. Ibrahim Thorlie is in charge of the fistula treatment program at the Princess Christian Maternity Hospital in East End, Freetown. He says the facility is overwhelmed but does not have enough funds to treat everyone seeking help.

“We have a ward where we used to have them operated on and kept for some time until [they were well enough to go home],” he says.

"We closed it because NGOs and foreign governments who gave us funding went away, and now we don’t have the money we need to maintain the program.”

These patients deserve special attention, says Thorlie, despite limited resources.

“[These are] women who really need to be taken care of because they are normally neglected even though it is not their fault. We’ve tried a lot, we’ve treated a lot, we’ve operated on over 800 cases here,” he says.

“But we still have others. The ones we have in greater number are those whose conditions have become so difficult that their bladder cannot be repaired.”

Improved training

A citizen of Freetown, Seku Sesay, says the incidence of fistula can also be traced to traditional birth attendants [TBAs] who don’t have the skills to know when pregnant women need prompt medical attention.

“We need to train more nurses [in Western medicine],” he says, “build infrastructure for hospitals [and] clinics, bring in more instruments and medicines and then invite educated non-governmental organizations, or NGOs, or any outside educated doctors or nurses.”

That view is shared by government officials, who this year introduced free pre-natal care for women. Efforts are also underway to boost the numbers of trained midwives and traditional birth attendants (TBAs). Some groups are training TBAs to recognize the signs of potential complications, such an undersized pelvis, and arrange early transportation to the nearest clinic.

International help is also available.

The US Agency for International Development (USAID) is providing financial support to an international non-governmental organization called Mercy Ships, which provides a fleet of hospital ships to help train surgeons and provide surgery for fistula in Freetown. Four years ago, the group opened the Aberdeen West Africa Fistula Center. The hospital can hold up to 44 recovering patients and two dozen more awaiting surgery. Talks are underway to see if the center can be incorporated into the national health system or whether another organization can take over operations.

USAID also supports maternal health programs to help educate women about emergency obstetrics care for protracted labor, which can lead to fistula. It partnered with EngenderHealth, a private NGO, to provide surgical services designed to reverse the effects of fistula.

Since 2008, the program has provided surgery for about 700 women. It trains surgeons and nurses to care for women with childbirth injuries and plans to help prevent fistula by working with local health providers, communities, and NGOs to counter the cultural practice of child marriage, which often leads to early pregnancies and fistula.

This is part 9 of our 15 part series, A Healthy Start: On the Frontlines of Maternal and Infant Care in Africa