It was almost a century ago that a young Lakota Indian, James Emery, was sent away from his home on South Dakota's Rosebud Indian reservation to boarding school in the central state of Kansas. When he returned several years later, he was alarmed to notice changes in the way his language was being spoken. Folks had begun to shorten words, a phenomenon that linguists call "clipping."

"Once you start clipping words, soon it becomes commonplace," said his grandson Randy Emery, a cultural resources management specialist in Rosebud. "And every time that expression is used, you lose a little bit more of the language."

Fearful that the Lakota language would someday be lost forever, the elder Emery began recording native speakers whenever he got the chance.

"He started recording on old Edison cylinders," said his grandson, "then he went to reel-to-reel and eventually cassette tapes."

By the end of his life in 1977, the elder Emery had amassed hundreds of recordings of some prominent Lakota, including survivors of the historic battle of Little Big Horn. Today, those recordings are housed in South Dakota's Black Hills State University and serve as a valuable resource for language preservationists.

Languages die with elders

But preservation is only half the battle. If the Lakota language is to survive, it must be passed on to subsequent generations. Today, only a few thousand fluent speakers remain, most of them in their 60s and 70s. Each year, as many as 200 of them die, taking the language with them.

Before the arrival of Europeans, as many as 250 languages were spoken across what is now the continental United States. Today, dozens are critically endangered and 50 are extinct. Wukchumni, a language that once flourished among California's Yokut people, is now spoken by only one person, an 81-year-old woman.

The decline in language is largely due to a long-standing U.S. government policy that required many Indian children to be placed in boarding schools, where they were punished for speaking their native languages. By the mid-20th century, languages began dying.

‘Sneak and speak’

Nearly every Native American who spoke with VOA told a story similar to that of Julz Rich, 42, a resident of Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota.

"My grandparents spoke it, but my parents didn't,” she said. “My grandparents had to sneak and speak Lakota. They were afraid because they would get beaten or deemed crazy."

"I heard my grandparents speak it," said Denver, Colorado, resident Gabriel Black Elk, also a Lakota, "but they never pushed it on me."

Black Elk can say a few words in Lakota, and encourages his children to participate in the sweat lodge — a purification ritual central to traditional Lakota culture — and other ceremonies.

‘Total immersion’ needed

Wilhelm Meya heads the Lakota Language Consortium in Bloomington, Indiana, a group of linguists and educators dedicated to preserving and reviving Lakota. He also is the executive producer of a new film, “Rising Voices,” which showcases efforts to teach Lakota to school-aged children.

"Our main focus is to try to increase the real number of speakers that the language has," Meya said. "So far, we've only created about a hundred."

These programs, while successful, can serve only a small number of children and face constant budget threats.

"To truly be effective, we need to mainstream the whole notion of teaching all content in the target language, that is, total immersion in all the schools," Meya said. "And it's not just in Lakota, but in dozens of languages across America that are taking their final last breaths. And unless the government applies more resources, I think we will lose them forever."

Far more than just words are at stake, according to Anton Treuer, an Ojibwe Indian and professor at Minnesota's Bemidji State University. He defines language as a distinct body of knowledge containing a unique worldview.

"For example, in Ojibwe, our word for elder, gichi-aya'aa, literally means ‘great being.' And our word for an elderly woman, mindimooyenh, means ‘one who holds things together' and describes the role of a family matriarch," he said. "We don't have to remind youth to respect their elders because it's built right into the language."

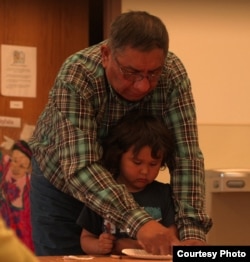

Darrick Baxter, an IT specialist and Ojibwe native living in Winnipeg, Manitoba, hasn't spoken Ojibwe since he was a teenager, but decided he wanted his daughter to learn the language.

"I bought her a bunch of books and audio CDs, but she never even opened them up," he said. "So I had one of my friends record a whole bunch of Ojibwe words and common phrases, I taught myself how to program them into an app, and I put it onto her iPad. And pretty soon, she was talking to her grandmother in Ojibwe for the first time ever."

As word of his app spread, Baxter began getting phone calls from tribal groups as far away as Norway and Africa.

"That's when I decided to release the source code for free," he said.

In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Languages Act, repudiating former policies and giving Native Americans the right to use their indigenous languages anywhere, including "as a medium of instruction" in schools. In 1992, Congress updated that act, authorizing grants to help the effort.

Congress is considering two additional bills, the Native Language Immersion Student Achievement Act and the Native American Languages Reauthorization Act, which would increase financial support and ease restrictions for immersion programs across the country.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story mistakenly affiliated the Lakota Language Consortium with the University of Indiana and misidentified Wilhelm Meya as Director of the film, 'Rising Voices.' We regret the error.