Every autumn, tens of thousands of sportsmen from across the globe descend on rural South Dakota, the pheasant hunting “capital” of the world. That’s good news for the state’s hotel, restaurant and sporting goods store owners. It’s very bad news for victims of sex traffickers, some girls as young as 14, brought every year from as far away as Las Vegas, Nevada – or as close as the nearest Indian reservation.

“If you are a trafficker looking for the perfect population of people to violate, Native women would be a prime target,” said Sarah Deer, an attorney, law professor and author of The Beginning and End of Rape: Confronting Sexual Violence in Native America.

“You have extreme poverty. You have a people who have been traumatized. You have addiction to alcohol and drugs as a result of trauma. And you have a legal system that doesn’t step in to stop it,” Deer said.

Federal law defines sex trafficking as the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act in which the act is induced by force, fraud or coercion -- or if a person forced into sex acts is under the age of 18.

Making matters worse, sparse law enforcement in rural areas, gaps in the law and conflicts over jurisdiction on Indian reservations mean that sex traffickers know they can get away with their crimes.

“Traffickers know who to target,” said Lisa Heth, executive director of the Wiconi Wawokiya ("Helping Families") shelter in Fort Thompson, on the Crow Creek Indian Reservation.

“There are certain signs that I’m sure that they can see when a young girl’s self-esteem isn’t that great or she may come from a family where there is domestic violence or there’s alcohol or drugs, where she’s not getting that attention or love at home," she said.

That’s when the traffickers start “grooming” their victims with expensive gifts and promises of a better life.

“We’re also seeing traffickers coming into the reservation and selling drugs,” Heth explained. “Sometimes they get these young women to sell for them, and then if they end up owing these guys money, then the guys traffic them out for sex to get money back from them. If the girls resist, the perpetrator will beat them up, threaten them or their families, rape them, or in some cases, have them gang raped.”

During hunting season, young women are exploited and prostituted in strip clubs and so-called “gentleman’s clubs,” some of which are open only during the hunting season, from October til early January.

Forced prostitution of native women also is a problem in oil fields, forestry projects or fracking operations such as the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota and Montana, where transient workers, almost exclusively male, are housed in remote “man camps.” Sometimes these amount to little more than a collection of trailers in a field, far from the prying eyes of law enforcement, and are fertile ground for drugs, gambling and sex trafficking.

“Groups of men from the man camps use free access to drugs and alcohol as a method of coercion for young native women to ‘get in the car’ and go party. This has resulted in 11 young Native women ranging from the ages of 16-21 years of age reporting rape, gang rape and other sex acts; the majority of these victims are afraid to report due to fear and shame,” Lisa Brunner, former spokesperson for the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center, told the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee in 2013.

Elsewhere, for generations, Dakota and Ojibwe women in Minnesota have been trafficked from their reservations onto the boats in the port city of Duluth and prostituted in the international waters of Lake Superior. Some women are sold to ships’ crews and forced to remain onboard for months at a time.

Legacy of violence

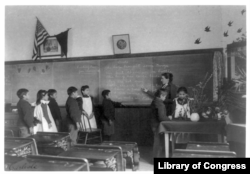

It is impossible to discuss the trafficking of Native youth outside of the context of history, especially the so-called “boarding school” and “relocation” eras, which were part of a long-standing campaign to indoctrinate and assimilate American Indian children into non-Native culture.

From the 1800s to the early 1900s, many Native children were taken from their homes and forced to live in government-run boarding schools, where they were harshly punished for speaking their own languages or practicing their religions.

Between 1941 and 1967, as many as one-third of Native American children were removed from their families and placed in foster homes, the vast majority non-Indian, according to a 1976 report by the Association on American Indian Affairs. Stripped of family support and tradition, they were easy targets for physical and sexual abuse.

Lynn Eagle Feather, now in her 50s, was born on the Rosebud reservation in South Dakota. When she was six, she and her siblings were abandoned by their mother and sent to the Saint Francis Mission School at Rosebud until they could be placed in foster care.

“The first person to ever hit me was in boarding school. An old nun with a German accent hit me with steel scissors on the side of the head," Eagle Feather remembered.

"Later on, I went into foster care in Lincoln, Nebraska. I was abused there also. Physically, sexually, emotionally. Once, I got pushed down a flight of stairs.”

Sunny Red Bear, 28, a Lakota, was removed from her family on the Cheyenne River Reservation when she was only two days old and placed with a non-Native family who lived on the reservation and later adopted her formally.

“My adoptive father started abusing me when I was really young, maybe about four. It continued on until middle school or so,” she said, adding, “He was a very Christian man and he used God kind of as leverage to me, growing up.”

At 17, Red Bear ran away from home.

“I remember I was cold and hungry, I would talk to guys. They would ask me if I wanted to come home with them, and I was, like, ‘Yeah, I’d love to have a bed to sleep in tonight.’ It wasn’t just one guy, it was multiple guys. And I remember I wouldn’t sleep with them and they would get really mad.”

Today, a mother and successful fashion model, she uses her career as a platform to speak to young Native women about the dangers of trafficking.

“Sometimes when I speak, it’s very blunt and real, not sugar coated. I know that people feel awkward,” Red Bear said. “I want them to take that little bit of awkwardness, multiply it by a thousand, a million, and then maybe they can imagine how trafficking victims feel.”

A way out

There are shelters that offer housing to victims of abuse, but most offer residence for no more than 30 days.

"Thirty days to get your life back in order? That’s just not realistic," she said.

Recently, Heth purchased a vacant motel she plans to convert into the "Pathfinder Center," South Dakota’s first dedicated “safe house" for rescued trafficking victims.

"The mission is to help them heal and become self-sufficient," she said. "Pathfinder will help them find their true purpose in life, to focus on the talents they might not know they have and fulfill their dreams that they had as children."

The U.S. Justice Department reports that sexual violence in American Indian/Alaska Native communities is “epidemic.” Native Americans experience sexual assault at a rate of 2.5 times greater than other races. A third of all Native women will be raped.

President Barack Obama has pledged to invest in helping trafficking victims rebuild their lives. In 2014, Federal agencies announced a five-year plan to combat human trafficking.

As part of that plan, the FBI will broaden community outreach to American Indian/Native Alaskan law enforcement agencies, community leaders and social service providers.

This year, the U.S. Department of Justice Office for Victims of Crime awarded more than $22.7 million to programs working to combat human trafficking and an additional $8.1 million to a dozen victim service organizations across the country – among them, Wiconi Wawokiya.

Those funds, says Heth, will go a long way toward ensuring that the Pathfinder Center opens, as scheduled, in early 2016.