Chippewa citizen John Wallette was 20 years old in 1910 when he left his home on the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in North Dakota and enrolled at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. There, he trained as a blacksmith, played left end on the school football team and spent at least three summers on “outings,” laboring on regional farms.

His parents, Moses and Melanie, were thrilled to welcome him home five years later.

But many other parents who sent their children to boarding schools in the 19th and early 20th centuries weren’t so lucky. Some children died at school, some died shortly after returning home sick, and many simply disappeared, their fates unknown.

This week, Native Americans have welcomed the first volume of a long-anticipated U.S. Interior Department report that follows a nine-month probe into federal Indian boarding schools.

"The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies — including the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old — are heartbreaking and undeniable," Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland said in a statement Wednesday. She expressed hope that this would be the start of a healing process for “Indian Country, the Native Hawaiian Community and across the United States, from the Alaskan tundra to the Florida everglades, and everywhere in between.”

Native reaction

“This is really personal for me,” said Wallette’s granddaughter, Christine Diindiisi McCleave, who admitted she cried while reading the report.

“As a descendant of boarding school survivors and as the former CEO of the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), I worked for six years to try and advocate for truth and justice and healing. I feel like this report is very validating for survivors and descendants to have the Department of the Interior and the federal government acknowledge that,” she told VOA.

NABS, a nationally recognized nonprofit organization, collaborated with the DOI for months to develop the report. In a statement released Wednesday, NABS CEO Deborah Parker, a member of the Tulalip Tribes in Washington state, called the report’s release a “historic moment” that reaffirms the stories Native Americans have grown up with and the “immense torture” elders and ancestors experienced in these schools.

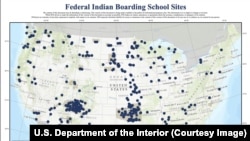

Preliminary findings, detailed by Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Bryan Newland in the 106-page report, show that between 1819 and 1969, the federal government “operated or supported” 408 boarding schools in 37 states or former territories, including 21 in Alaska and seven in Hawaii. Previously, NABS had counted only 367 schools.

So far, investigators have discovered marked and unmarked graves at 53 schools and counted 500 student deaths, but the DOI anticipates the number of dead could ultimately rise to the “thousands or tens of thousands.” The report does not say how the children died or who was responsible; VOA has previously reported that many died from infectious diseases that thrived in crowded school dormitories.

The report confirms that schools used “systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies” in their effort to Americanize Native children, giving them English names, banning their languages and cultural practices, and organizing children into units to drill like soldiers.

Former Osage Nation Principal Chief Jim Gray, whose great-grandfather Henry Roan also attended the Carlisle school says the report is a good first step, but more work is needed.

“The policy of the day was to ‘kill the Indian and save the man,’” he told VOA via Facebook. “The discovery of unmarked graves around these schools is testament to the fact that this policy was cruel and a complete failure. This country needs to acknowledge this disaster and stop pretending it didn’t happen and stop trying to whitewash its long-term impacts of generational trauma.”

Sunny Red Bear is a Lakota from the Cheyenne River Reservation South Dakota and director of racial equity at the NDN Collective, an Indigenous-owned advocacy group based in Rapid City, South Dakota. She said that while she welcomed the report, it represented only the first step in the long road toward healing.

“The children aren't home,” she said. “I think that they need to be brought home, and we really need to get some answers, because this is a huge part of our history as Indigenous people — the erasure of our culture, our languages, our stories. We really need to get to the bottom of it.”

Looking forward

Secretary Haaland this week announced the launch of “The Road to Healing,” a yearlong tour across the U.S. to give American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian survivors of the federal Indian boarding school system a chance to share their stories, to help connect communities with trauma-informed support and to begin work on collecting a permanent oral history.

On Thursday, the Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States held a legislative hearing on a proposed bill that would establish a truth and healing commission to study the impacts and ongoing effects of the federal Indian school policy, to be patterned after a similar commission in Canada.

If passed, H.R. 5444, sponsored by Kansas Democrat Rep. Sharice Davids, an enrolled member of the Ho-Chunk Nation in Wisconsin, would establish a truth and reconciliation commission to investigate the historic and present-day impacts of forced attendance at the boarding schools. The commission would also work on ways to protect unmarked graves, support repatriation of children’s remains, and identify the nations from which they were taken.

Further, the legislation would work to stop state social services, foster care and adoption agencies from removing Native children from families and communities, a practice still prevalent in states across the country.

NABS is requesting people who attended a boarding school or who descend from boarding school students to submit written testimonies to the U.S. House of Natural Resources Committee by May 26th.