Editor’s note: This report reveals information about illness and death in federal Indian boarding schools that some readers could find triggering or upsetting. Discretion to sensitive groups is advised.

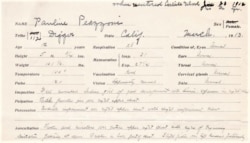

On June 16, 1913, Pauline Peazzoni, a 13-year-old Maidu girl from the Sierra Nevada of Northern California, lost her battle with the “white plague,” tuberculosis.

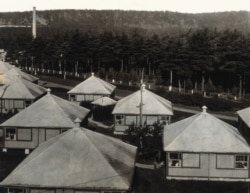

She had spent seven months at the Mont Alto Sanatorium in Pennsylvania. A former U.S. Forestry Service camp, it was now a cluster of cottages, bathhouses and an infirmary in the middle of a mountaintop forest – a place where Pennsylvania sent indigent TB patients to be cured or die.

Industrialization and the resulting rise in immigrant populations during the late 19th century led to waves of pandemics – cholera, typhoid, diphtheria – but none terrified Americans more than tuberculosis (TB), which could attack the lungs, lymph glands or abdomen. Sometimes called phthisis or consumption, it was a leading cause of death in the U.S. until the development of antibiotics in the 1940s.

Science had long known that infectious disease thrived under dark, damp, dusty and airless conditions. In 1865, the New York City Council of Hygiene and Public Health surveyed housing conditions and concluded that improving sanitation could reduce mortality by 30%.

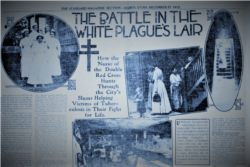

By the early 1900s, the Red Cross and newly formed American Lung Association launched aggressive public health campaigns about cleanliness and hygiene; by 1910, at least 65 open-air schools were in operation across the U.S.

‘Famishing wretches’

On May 7, 1880, Montana’s Benton Weekly Record reported that Blackfeet, Blood and Piegan tribes were dying of starvation amid horrifying living conditions at Fort Assinniboine.

“The swill barrels around the soldiers’ and officers’ quarters are besieged day and night with crowds of famishing wretches,” the correspondent wrote, “and the putrid carcasses of animals that have died from disease are stripped of every particle of flesh to relieve the keen pangs of hunger.”

In their annual reports to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, most bureau agents and physicians downplayed substandard conditions on reservations. But some were more truthful.

Newly appointed agent to the Blackfeet Agency in Montana, R.A. Allen, reported in 1884 that “little children … were so emaciated that it did not seem possible for them to live long, and many of them have since passed away.”

Infectious diseases flourished on reservations. By 1898, Blackfeet physician Z.T. Daniel reported that “nearly all Indian children” were infected with TB.

Many blamed the Indians themselves, citing lifestyles, cultural traditions, degree of Indian blood or genetic weakness.

“Civilized people in any good climate do not die at such rate,” wrote Yankton Agency (S. Dakota) R.J. Taylor.

But Washington Matthews, a U.S. Army surgeon who had spent decades working with tribes, scoffed at the assertion. In his 1886 report for Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, “Consumption Among the Indians,” he used statistics to demonstrate that TB deaths were higher among Indians who had been “civilized,” that is, forced “to accustom themselves to the food and the habits of an alien … race.”

Into the dormitory

In 1891, Congress authorized the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to create regulations making it mandatory for Indian children to attend boarding schools and authorizing reservation agents to withhold rations and other benefits to any parents refusing to comply.

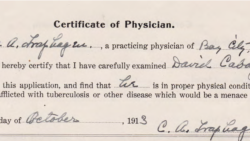

“No pupils must be transferred who are not in sound and vigorous health,” read the Indian Bureau’s new “Rules for Indian Schools.”

“Students would have to be examined by reservation doctors, who would certify them to be physically sound,” said Dartmouth College historian Preston McBride, who has documented at least 1,000 deaths in four boarding schools from 1879 to 1934 and spoke with VOA in June. “And then once again, by school physicians, upon arrival.”

But these exams were rarely comprehensive and often lasted only a minute or two, “long enough to record a student’s height, weight and pulse,” McBride said.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs “rules” admitted that “frail, unhealthy and positively diseased” students had slipped into schools through the cracks.

“School officials didn’t always separate them from other students,” McBride said. “There’s evidence that in some cases, tubercular students would have to share beds with healthy students.”

‘Shanties and shake-houses’

The 1886 report to the Commissioner contains several grim reports about boarding school conditions.

“No arrangements for sewerage have ever been made,” superintendent of the Fort Stevenson Industrial School in North Dakota, George W. Scott, wrote. “The slops from the kitchen found a receptacle in a hole a couple of rods (about 3 meters) from the kitchen.

Both students and teachers, he added, were getting sick from drinking contaminated water.

Meanwhile, Horace Chase, superintendent at Nebraska’s Genoa Industrial School, had similar complaints: “All water for whatever purposes is brought into the building by bucket or tub, and in the same manner, must it be carried out. Sufficient means are not and cannot … be provided for bathing purposes.”

And the Forest Grove Indian Training School — the second federal off-reservation boarding school — was transitioning from its original location in Forest Grove, Oregon, to the nearby town of Chemawa, where residents were crowded together in temporary “crude shanties and shake-houses,” which they had built themselves.

Student health, according to the new school superintendent, was “as good as could be expected.”

“There were 510 cases treated by the physician, but of this number only 6 died in the school and 2 after returning home,” he wrote, reflecting a practice found in many schools of sending sick children home to die.

As David H. DeJong noted in a 2007 article for the American Indian Quarterly, “Unless They Are Kept Alive,” Indian Affairs Commissioner William Jones ordered a survey of Indian health in 1903 and called for schools to step up efforts to screen students and improve building conditions.

But agencies were slow to implement change. Records at the Carlisle School state that Pauline Peazzoni had already lost her mother and sister to TB and suggest she may have been infected on arrival at school. In 1907, the “frail and delicate” girl was placed on an “outing” with a white family in Bucks County, 200 kilometers away from the school.

When she returned to Carlisle in June 1912, her disease had advanced. She was hospitalized at Carlisle for four months, then transferred to Mont Alto to live out her final days.

As VOA reported in June, surveys of boarding schools in 1922 and 1928 showed that conditions in boarding schools had, in some cases, only worsened.

The task ahead

In May, the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc Nation in British Columbia announced that using ground-penetrating radar (GPR), they had found the remains of more than 200 students at the Kamloops Indian Residential School – news that stunned the public but was not a surprise to First Nations, Native Americans and Alaska Native peoples who, for decades, have talked about student disappearances and deaths in boarding schools.

This prompted Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to launch a national investigation into the fates of boarding school students in the U.S. The findings are to be released in April 2022.

But will we have a full accounting?

Frank Vitale, a historian who consults with Dickinson College’s Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, told VOA prospects may be slim.

“Boarding schools in the United States were run by a number of different groups, including the federal government and various religious organizations,” he said. “And they were run in different ways in different locations and different periods of history, right up to the 1960s.”

Record-keeping was spotty, so accounting for individuals will be challenging and will involve looking not just at student information files but financial records, annual reports from schools and administrative correspondence.

“For example, we looked at daily attendance ledgers at Carlisle and noticed a student dropped off for an unknown reason that wasn’t recorded,” Vitale said. “So, we went digging and finally found a financial record that showed that a coffin was purchased around the same time.”

Vitale believes that while tracking these students is important work, focusing too closely on assigning blame misses the greater questions:

“What do the statistics tell us about the experience of Native Americans in the 19th and 20th centuries?” he asked. “And how does their suffering and death from tuberculosis link to the larger system of American imperialism?”

NOTE: In part four of this series, VOA will examine the impact of boarding schools on the students, their families, their tribal communities and descendants.