U.S. officials are scrambling to assess how this past Sunday’s Italian election results may impact future relations between Rome and Washington.

The prospects of euro-skeptic populist parties that have strong ideological ties with the Kremlin forming Italy’s next government or dominating a broader governing arrangement has prompted alarm in the U.S. capital and Brussels.

An immediate consequence of either the right-wing Lega or anti-establishment Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S) entering a coalition government could be the “curtailment of a lot of intelligence we currently share,” say U.S. officials.

“There would a sharp downgrading of what we give the Italians, although this wouldn’t affect our exchanges when it comes to jihadists or terrorist threats,” a U.S. counterintelligence official told VOA on condition of anonymity.

U.S. security agencies are already starting to assess what intelligence could be supplied, given the higher risks of leaks to Moscow, says the official. “Security risks would increase obviously,” he added. Who’s appointed to head Italy’s foreign and security ministries as well as security agencies could define the tightness of any restrictions, he said.

That will depend on what coalition government is shaped after an election that saw M5S emerge as the largest single party and a right-wing coalition led by Silvio Berlusconi secure the largest bloc of seats. Negotiations could drag on for weeks and may end up with Italian President Sergio Mattarella underpinning a grand “government of the president.”

Party ties

Roberto Jonghi Lavarini of Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy), a far-right sister party of the Lega, which is part of the right-wing coalition that includes Berlusconi’s own Forza Italia, told Russia’s Sputnik TV his party is already angling to secure either the interior or defense minister positions in addition to several deputy ministerial posts in any right-wing coalition government that is formed.

He said such a government would work on lifting the Western sanctions imposed on Russia after the Kremlin annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014 and pursue “a privileged dialogue with Moscow." His party would push, he said, for a revision of all international treaties, including those governing Italy's membership of the eurozone and NATO, in favor of a strategic tie-up with Russia.

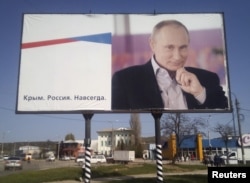

M5S and Lega oppose Western sanctions, saying the sanctions have harmed Italy as much as Russia. In 2016, several Lega-controlled regions in Italy’s north adopted resolutions calling on the government in Rome to approve Moscow’s annexation of Crimea and recognize the peninsula as part of Russia.

In the same year, a delegation of politicians from the Lega and Fratelli d’Italia, alongside half-a-dozen Italian business people who had been impacted by the sanctions, visited Crimea.

Like other Kremlin-leaning anti-establishment and far-right parties in Europe, Fratelli d’Italia, M5S and Lega have been courted assiduously by Moscow as have other European populists sympathetic to Russian President Vladimir Putin that are eager to embrace Russia as a counterweight to the European Union. The Lega has a cooperation agreement with Russia’s ruling party, United Russia.

M5S members have praised Moscow's military intervention in Syria to prop up President Bashar al-Assad and railed against NATO, blaming it for fomenting Ukraine’s Maidan protests that ousted Moscow ally Viktor Yanukovych. M5S has also called for lifting EU sanctions on Russia. Italy is the second biggest exporter to Russia in the EU and has seen its exports fall by nearly half.

Italy-Russia-Western relations

Relations between U.S. and Italian intelligence agencies are not as close as they are with some other Western and NATO countries.

Intelligence relations between the United States and Italy were impaired in 2009 when an Italian court convicted in absentia a former CIA station chief and 22 other Americans, almost all agency operatives, for their involvement in the kidnapping of a Muslim cleric from the streets of Milan in 2003 and his rendition to Egypt.

A strong domestic Communist Party made sure Italy stayed on the margins during the Cold War, and Christian Democrat governments eagerly pursued business and energy deals with Moscow. Italy supplied half of all the industrial equipment the Soviet Union imported in the 1960s, and Fiat built a massive car manufacturing plant in a town that was renamed Togliatti, after an Italian Communist Party leader.

Center-left and center-right Italian governments have eagerly pursued business and energy deals with Russia since the fall of the Berlin Wall, none more so than administrations headed by Berlusconi, who formed a close friendship with Putin. In 2015, Berlusconi also visited Crimea with Putin.

Speaking Monday in Moscow, Leonid Slutsky, chairman of the foreign affairs panel in Russia's lower house of parliament, or State Duma, said given the election’s outcome, he had “no doubt” Russian-Italian relations would improve.

In 2014, in the wake of revelations that France’s National Front had received Russian loans, Matteo Salvini, Lega’s leader, denied his party had ever received funding from Moscow.