Ibrahim, a 35-year-old Moroccan who hawks bracelets weaved out of multi-colored fabric in front of Milan's cathedral, teared up when he spoke of the family he left behind and which relies on the money he sends home.

"I really hope they don't make it even more horrible to stay in this country," he said. "I want to stay here."

Up and down Italy on Monday, migrants, both legal and not, were pondering their future after the anti-immigrant League surged in popularity in elections the day before.

Ibrahim, who declined to give his last name, is one of the lucky ones. He has permission to stay because he once worked in a factory, but it comes up for renewal every two years.

"It often happens that we have problems, that people shout at us 'go back to your country'," he said.

That is precisely what the League, which shot up 14 percentage points from the 2013 national election, and its three center-right coalition partners, would like to see happen: immigrants going back where they came from, by force if necessary.

The center-right has vowed to deport hundreds of thousands of migrants if they are able to form a government, even though that promise will be hard to keep.

Surveys show Italians are increasingly uneasy after more than 600,000 migrants reached Italy by boat in four years. Last month, a neo-Nazi wounded six migrants in a shooting spree in central Italy.

'Pick them up'

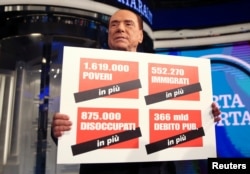

"These 600,000 people, we will pick them up using police, law enforcement and the military," former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, of the Forza Italia (Go Italy!) party, said during the campaign.

League leader Matteo Salvini said irregular migrants would be rounded up and sent home "in 15 minutes" if he and his allies take power.

League supporters were thrilled that they had overtaken Berlusconi's party as the largest in the center-right bloc for the first time since he entered politics nearly a quarter of a century ago.

"With Salvini in government, the problem of immigration can and must be resolved," said Severino Damiolini, 43, an office worker from Sellero, near Brescia in northern Italy.

The immigration debate also highlighted splits between immigrants who have been in Italy for years or decades and more recent arrivals, with the former fearing that their reputations are tainted by the newcomers.

"The League should not lump all of us together - Indians, Asians, Africans," said Kris Sumun, 35, who came from Mauritius when he was five years old and has worked as a concierge in a Milan building for 11 years.

"They have to understand that there are many people like me who have been here for years and are a resource for the country.

People who have a different skin tone are all treated like we are all wretched and poor," he said. "I think it will get worse now."

Next to Rome's Tiburtina train station on Monday, buckets of rain poured onto tents that are home to hundreds of migrants who made their way to the capital after making the perilous crossing of the Mediterranean from North Africa.

"Very few politicians have told the truth about migration," said Andrea Costa, who oversees the site for a charity.

"There is no invasion in Italy. It's not a siege. It's not a crisis. It's an issue that has to be governed like all other issues," he said.