NAIROBI —

As rhino and elephant poachings continue at alarming rates across the Africa continent, in some countries the penalties for illegally hunting endangered species remain unchanged.

Based on legislation enacted in 1976 and revised in 1989, Kenya's outdated wildlife laws haven't keep pace with unregulated-market values: in China, elephant tusks can bring an estimated at $900 per kilogram whereas the same amount of powdered rhino horn can fetch an astounding $65,000.

Confronted by what has long been described as a new breed of poacher — highly sophisticated and well-resourced international crime syndicates that use paramilitary tactics and employ game ranchers, hunters and veterinarians to acquire tusks and horns — Kenya's fines are negligible when compared to the commercial stakes.

Offenders caught with illicit game meat, for example, face fines of no more than $235 or a prison sentence of no more than three years, while those caught with illegal game trophies faces fines of no more than $120 and prison sentences not exceeding one year.

Offenders caught with illicit game meat, for example, face fines of no more than $235 or a prison sentence of no more than three years, while those caught with illegal game trophies faces fines of no more than $120 and prison sentences not exceeding one year.

In a world where the price of powdered horn competes with comparable amounts of heroin or cocaine, offenders have little to lose if caught.

“People just go into the court, they admit the offense, pay the penalties, give up what they were caught with and leave," says Helen Gichohi, president of the African Wildlife Foundation. "They know if they are caught, there is going to be a slap on the wrist and they will be let go, and they can go and try again.

"The risk is very low compared to the size of the reward," she says, describing it as part of a Kenyan culture of impunity, where even basic driving laws go unenforced. "What they are earning here is many, many times higher than they will ever be required to pay in a court of law.”

Harsher penalties, community engagement

While the Kenyan Cabinet recently prepared new wildlife legislation for parliamentary review — which, if passed, would apply stringent penalties — Didi Wamukoya, chief prosecutor of the Kenya Wildlife Service, says adequate investigatory tools are also critical.

Poachers, she says, often escape punishment due to poor forensic capabilities.

“Sometimes you have a carcass, then three months later ivory is recovered somewhere, but we do not have the capability of connecting that ivory with the elephant which died," she says. "You end up charging the person with the ivory possession only — you cannot connect him to the death of the elephant."

Kenya recently broke ground on a new forensics laboratory that offers DNA analysis that will enable investigators to match seized ivory with a given carcass. While securing evidence against poachers will undoubtedly provide prosecutors an edge in court, World Wildlife Fund attorney Gladys Warigia says application of harsher laws and grassroots education is still essential.

According to the newly prepared legislation, she says, fines for possessing trophies of endangered species could expand to as much as $58,000 and a minimum imprisonment of five years. Combined with efforts to raise public awareness about poaching in the local communities, she says, the new policies could combat the crisis.

“You put harsh penalties and maybe the strict enforcement of these laws, I am sure it will just go down," she says. "[But] you involve the communities and sensitize them on the importance of wildlife to their lives and all that, the economy, I think that holistic approach will improve things.”

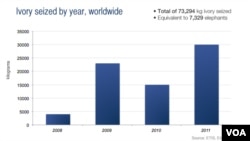

According to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, tens of thousands of African elephants are killed each year to supply the market with between 50 and 120 tons of ivory. An estimated 800 kilograms of illicit rhino horn reach Asian markets each year.