DAKAR —

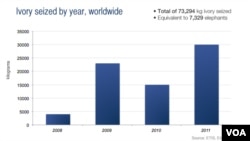

Last year, African conservationists saw the highest level of elephant poaching in more than a decade, and ivory seizures were at their highest recorded levels since 1989 — the year that international trade in elephant ivory was banned.

During 2011, more than 20,000 elephants were slaughtered for an estimated 24,000 kilograms of ivory, and wildlife officials also noted a drastic increase in large-scale seizures (more than 800 kg in a single transaction) since 2009.

The large-scale shipments, experts say, indicate the presence of organized crime. While some Africa-based wildlife officials point to primarily Asian-led crime syndicates, they refuse to provide further details for fear of jeopardizing on-going investigations.

The large-scale shipments, experts say, indicate the presence of organized crime. While some Africa-based wildlife officials point to primarily Asian-led crime syndicates, they refuse to provide further details for fear of jeopardizing on-going investigations.

With ivory's market value reaching $900 per kilogram in China, the financial stakes are high, and it appears sponsors are adopting bold new tactics to satisfy demand.

"One criminal syndicate will gather a poaching gang together, and that poaching gang will be assigned instructions to kill a specific herd of elephants or to provide a specific amount of ivory," says William Clark of Interpol's Environmental Crime program. "We're finding that, consistently, in all of the large seizures, the DNA says these animals were brothers and sisters, uncles, aunts, parents and children — very closely related. This is not opportunistically-poached ivory where some poachers killed two elephants up in the north of the country and four more in the south and some middleman collected it all together. Oh no. One specific population is targeted and exterminated."

Elephants are intelligent, social and affectionate creatures that, experts say, live in tight-knit family herds that mourn their dead, often staring silently at remains of the deceased.

One conservationist said gangs of poachers have been known to lie in wait to pick off elephants that got away during the initial ambush but instinctively return to the kill.

What's worse: In poaching hotspots such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Chad, gangs usually outnumber and outgun often under-resourced park rangers.

Fighting a war

According to Clark, organized crime is hiring gangs of up to 18 people, many of whom wear fatigues and adopt military-style techniques such as security patrols to guard their camps.

The variety of contraband seized proves the poachers are becoming more sophisticated. A recent raid conducted as part of Interpol's Operation Worthy — an anti-poaching and trafficking initiative that involves judiciary, customs, police, wildlife and even revenue services from 14 African nations — nabbed more than 30 military firearms, including AK47’s, G3’s and even M16’s.

"We ended up with 214 arrests, about two tons of elephant ivory, [and] a big variety of other wildlife contraband," said Clark, explaining that his group occasionally seizes drugs, illegal gold and even smuggled cigarettes. "But we are just starting to see them, in the past year or so, come in such increasing numbers [that] they’re starting to alarm people.

"[The M16] is a weapon that’s more accurate than the old Kalashnikov [rifle and sub-machine gun], with a greater range [and] more fire power," he said. "Even the wound made by an M16 bullet is much more tearing than the Kalashnikov, so it’s a more deadly, harmful weapon."

It's a war in which most Central African countries are frantically trying to catch up.

In Kenya, at least 15 wildlife staff have been killed this year, while five Chadian rangers were executed during morning prayers in September. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, mercenary and rebel groups like the Lord's Resistance Army are turning to ivory for income.

In Cameroon, where gangs massacred more than 300 elephants in Bouba N'Djida National Park, special forces have been deployed to keep Sudanese poachers from re-entering its reserves.

In Gabon, at least 100 soldiers are supporting rangers in 13 national parks.

Lee White, head of Gabon's National Park Service, said the country has more than quadrupled its parks staff in the past three years and increased its budget 15-fold to go after "organized gangs of specialist elephant hunters," primarily from West and Central African countries.

"We're doing three to four foot patrols per week through some of the remotest forests in Africa," he explained. "Basically walking through the forests, following elephant trails and then, if we hit human signs — if we get cut marks or cartridges or snares and so on — we try to track toward poacher camps and [make arrests]. We're using planes to some extent. We can spot campfires from the air and then we can direct the foot patrols by giving GPS points. We're traveling up rivers in canoes."

The street value of one kilogram of ivory in the Gabon-Cameroon region has skyrocketed from $50 to $350 since 2010, White said, explaining that savvy traders want to draw poachers to places like Gabon where large concentrations of elephants reamain.

Exponential profit increases

Wildlife officials say poaching gangs work quickly to move tusks out of the source country. Much of that ivory then makes it way to seaports in Kenya and Tanzania, where it is concealed in shipping containers bound for Asia. Most of the ivory ultimately lands in China and Thailand.

Customs officials in Hong Kong have made two large seizures in November alone, intercepting more than 5 tons of illegal ivory with an estimated street value of $4.8 million. The most recent seizure — 569 tusks, or about 1.3 tons — was found in a shipping container from Tanzania marked as carrying sunflower seeds.

According to Clark, the illegal ivory trade is worth an estimated $1.4 billion a year.

"An opportunistic poacher selling to a middleman can make about $70 to $100 per kilogram, or as much as $1000 from a single kill if you estimate 10 kilograms for an adult elephant," said Clark. "Crime syndicates tend to pay their poaching gangs monthly stipends."

Profits increase exponentially along the smuggling chain, and by the time those tusks are reduced into retail items in Asia — Clark took the example of the signature seal — that 10 kilograms of ivory from just one elephant can be worth as much as $60,000.

"Take a signature seal, which is a common use for ivory," he said. "It weighs about 30 grams so you can make 30 of them out of one kilo of ivory. So from a ton of ivory, you can make 30,000 of them. That’s a lot … They're retailing for about $200 a piece, a 30-gram signature seal.So the ivory is worth something close to $6,000 per kilo when it's reduced to the cheapest item that's fabricated from contraband ivory."

Localized training initiatives

Instead of engaging the criminals in a race for more sophisticated weapons, Interpol and its partners use policing methods based on human rights, including the right to be charged before a magistrate and the right to remain silent.

"Military armies go out intent on battle and killing enemy soldiers," said Clark. "A police officer goes out under the legal requirement to use the least force necessary to have the law enforced."

Interpol offers technical investigative assistance and training, and provides national police agencies with improved technologies, including night-vision equipment.

Poachers, he said, often surrender without a fight once they realize they’re surrounded, as many gangs march long distances to their destinations, giving authorities plenty of time to catch them.

"For example," said Clark, "some poachers come out of Somalia to poach elephants in Kenya, and they’ve got to walk a couple of hundred miles on foot. If there is pressure, [as from] a Kenya Wildlife Service unit [which can be refreshed from time to time with new people by helicopter], then you run [the poachers] until they’re really puffing. Then they won’t have as much fight as when they were starting the ordeal."

Interpol also helps customs agents recognize standard techniques that some criminals use to transport contraband, such as packing false walls of 20-foot steel shipping crates with timber, sisal or other products, or burying ivory in wet tea leaves to discolor it, since international law allows the sale of ivory purchased before 1989, which marked the signing of the convention protecting endangered wildlife.

Other smuggling techniques include wrapping contraband in aluminum foil to avoid X-rays or packing it in pepper to trick dogs trained to identify ivory by smell. One gang, he said, actually baked the ivory in clay pieces that were shaped like artifacts.

Groups like the International Fund for Animal Welfare, IFAW, have also been training and equipping rangers, police and customs officials in African and Asian countries, but say enormous challenges remain.

Director of IFAW's Wildlife Trade program, Kelvin Alie, said it takes a global effort to go after "the big fish."

"The person who is sitting in their office making that order for over a ton of ivory," he said. "These are the people we want to bring down because if we take these people off the chain, then we clearly are going to have a ripple impact down the line to the level even of the killing of the elephant for its ivory in Africa. So, we need to see more cooperation between the source countries in Africa and the end user countries in Southeast Asia."

Increased collaboration

Once the poachers are apprehended, said Clark, Interpol works closely with judiciaries in partner countries to ensure stiff sentences are applied. Often, he said, Interpol helps to shape prosecution so that it can be expanded to include multi-count indictments.

One of several free roaming elephants in the Bouba Ndjida National Park in northern Cameroon were killed by Sudanese poachers. (IFAW)"[For example], if this fellow was dealing in ivory, that’s an offense," explained Clark. "But he must [also] have cooked his books and held dual records and financial infractions: there must [also] be some unreported income, and if it’s unreported there must be some tax evasion. Maybe there’s some money laundering as well as common crimes such as fraud [and] conspiracy. Maybe [there are] other violations — veterinary, sanitary and a host of other laws we can enforce in countries where we have to make enough of case that justice will be served."

Interpol is planning to expand its African partnerships to included French-speaking countries and continue to work with China and other Asian countries to curtail demand for ivory products.

Interpol officials say by tackling wildlife trafficking in source countries, during shipping and in global markets, authorities can help prevent the extinction of the world’s remaining wild elephants.