Bombings and mass-casualty attacks have killed at least 270 people across Iraq since late December, according to tallies compiled by Western news agencies. The attacks have coincided with an Iraqi political crisis that has exposed deep sectarian divisions within the government.

Middle East analysts say that political tensions have created an unstable security situation making Iraqis more vulnerable to violence.

The Iraqi government vows to track down the killers, but there have been few claims of responsibility, save for an al-Qaida splinter group saying it was behind two of the attacks.

Ranj Alaaldin, a London-based Iraq expert at research institute Certus Intelligence, said gaps in security grow during political divisions.

“Iraq’s security is dependent on Iraqis presenting a united front and being sympathetic to each other," he said. "The existing political climate of extreme divisions and uncertainty leads to the opposite."

Alaaldin said these security gaps have helped Iraq’s main Sunni militant group, the al-Qaida-affiliated Islamic State of Iraq, carry out sophisticated mass-casualty attacks on Iraqi government targets in recent years.

Al-Qaida link

The Islamic State of Iraq claimed responsibility for a wave of bombings in mostly Shi’ite areas of Baghdad that killed about 70 people on December 22. It also said it carried out a January 15 raid on a Shi'ite-dominated government security compound in the western town of Ramadi, where seven policemen were killed.

Alaaldin said the group targeted majority Shi'ites because it wanted to provoke them into carrying out revenge attacks on Sunnis and push the country back to the brink of civil war.

But al-Qaida does not appear to be responsible for much of the other violence that has happened in Iraq since December.

Maria Fantappie, a visiting scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, said al-Qaida is no longer a significant force in Iraq because it has not been able to smuggle as many fighters into the country as in previous years.

Alaaldin said no terrorist group has a dominant foothold in the country.

“Iraq is flooded with ammunition and explosives,” he said. “It requires very little skill and planning for bandits to use these weapons to attack vulnerable civilian targets like markets or other crowded sites.”

Alaaldin said attacks also have been carried out by Shi’ite groups, including those who broke away from the former militia of Iraq’s radical Shi’ite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, and others backed by Iran, such as the Hezbollah Brigades.

He said some militants also collaborate with Iraqi government “insiders” who help them to penetrate rigid security checks around official buildings.

Security forces vulnerable

Iraq analyst Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington said the involvement of Iraqi security forces in the attacks cannot be ruled out.

“There are almost 600,000 Iraqi security personnel. Some of them almost certainly are tied to extremist groups,” he said.

But Cordesman, a former U.S. Defense and State Department official, said it's unlikely that the Iraqi government is complicit in the violence.

“It has not served anybody's interest,” he said. “It has not helped the Shi'ites, the Sunnis or the Kurds in the government. It has made them look weak and ineffective. And that seems to be another goal of the attacks.”

Analyst Fantappie said Iraqi troops and police have improved their ability to prevent attacks with the help of U.S. military training in the years leading up to last December's U.S. withdrawal from Iraq.

But she said the effectiveness of Iraq’s security system has been undermined by the political rivalries that have spread from the government to the highest ranks of the armed forces.

Shaky politics undermine security

Shi'ite Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has exercised control over those forces since December 2010, when he formed a unity government and appointed himself as the acting head of Iraq’s three security ministries - defense, interior and national security.

Maliki has used those powers to appoint top-ranking military officials. Cordesman said the Maliki government's awarding of security posts to its political allies has undermined the quality of Iraqi commanders and contributed to the country's endemic corruption.

Fantappie said the prime minister's consolidation of power also has fueled a sense of alienation among minority Sunnis and other Iraqis who support his main political rival - the Iraqiya alliance.

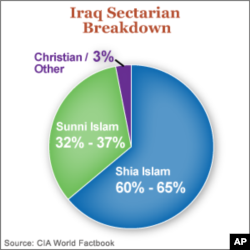

Iraqiya won the most parliamentary seats in Iraq’s 2010 elections but failed to form a coalition and joined a unity government led by Maliki's National Alliance, the main Shi'ite bloc. In recent weeks, Iraqiya has been boycotting the Cabinet in protest at being kept out of key government positions.

It also objected to Maliki's December decision to order the arrest of Sunni Vice President Tareq al-Hashemi on suspicion of running a death squad, a charge many Sunnis say is clearly politically motivated.

“You have Iraqi people who feel they have been completely pushed out of government, who have an increasing sense of non-representation,” Fantappie said. "This also can trigger some of Iraq's sectarian violence."