At first glance, the black-and-white photo suggests a sweet innocence. Nine neighborhood boys in knee pants cluster together, some smiling as they look directly at the camera.

The image, taken in 1929 in Bremen, Germany, introduces a dark story. Decades later, one of the photo’s subjects sent it to another, along with a letter in which he explained that he went on to become a Nazi guard at Germany’s Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and yet "never touched a Jew."

The letter’s recipient, shown standing with a bicycle, experienced his mother’s murder on Kristallnacht and eventually became a rabbi.

"What I wanted to hear from Gunther was how he felt about his job. Did he think that killing Jews was the proper thing to do?" the rabbi wrote to the sender. There was no reply.

Special exhibit

What motivates ordinary individuals? How would we behave in trying circumstances? Such questions arise from that photo and other artifacts in "Some Were Neighbors," a special exhibition of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. Subtitled "Collaboration & Complicity in the Holocaust," the exhibit challenges viewers to understand a sordid chapter of history and the importance of social responsibility.

"If an accident happens on the street, is it my business to act or not?" asked Zsuzsanna Kozák, who coordinated the project.

She thinks it can strengthen youngsters’ moral framework to act honorably "before we are paralyzed."

Kozák runs the Visual World Foundation, a Budapest-based non-profit organization to promote peace through media literacy education and video production.

Promoting peace

Last year, Kozák was among educators who gathered at the U.S. museum for an international conference on Holocaust education.

Organized by the museum and UNESCO, the conference brought in teams from 10 countries that have had limited curricula on the Holocaust or other genocide studies: Chile, Hungary, India, Lithuania, Mexico, Morocco, Namibia, South Korea, Rwanda and Turkey.

Each country’s team left with a project plan.

Hungary’s drew on the "Neighbors" exhibit to create a traveling student art installation highlighting the Holocaust and sparking public discussions about contemporary tensions such as the migrants blocked from the country by an imposing border fence erected last year.

The anti-discrimination project, called "Your Decision," trains bystanders to be "upstanders."

Kozák’s team worked with educators from six Hungarian schools – from elementary through college levels – whose students explored themes of tolerance and inclusion.

Each group studied "Neighbors" components such as the film clip of a Holocaust-era public shaming or the Bremen boys’ photo or another of witnesses to a 1943 police roundup of Jews in Amsterdam. Each group was asked to make art communicating the concepts they’d learned.

The students' collective works were unveiled at an exhibit last week in Budapest at the Canadian embassy, a major sponsor.

Youths, teachers and school psychologists connected in person after months of Facebook collaboration, and met with adviser Eva Fahidi, a Holocaust survivor.

Graphic messaging

Their focus was on the art and its graphic messaging.

Dávid Kovács, a student at the Secondary School of Art in the western Hungarian city of Szombathely, interpreted the 1943 Amsterdam photo as a crime scene with missing people.

Teenagers from the Lauder Javne Jewish Community School in Budapest made a 3-D rendering of the Bremen boys’ photo, separating the letter recipient and another boy from the rest.

'This is all about us'

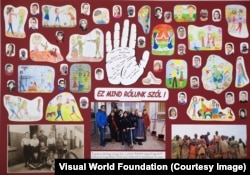

Students at Budapest’s Primary School for the Visually Impaired made a collage juxtaposing the Bremen boys’ photo with two similar images: one of Rwandan youngsters and another of themselves grouped around a skateboard.

They labeled it "Ez mind rólunk szól!" or "This is all about us!"

"People in Rwanda killed their neighbors based on the fact that there were different names written on their identity card: ‘Tutsi’ or ‘Hutu.’ It is as if we killed each other because one of us is Hungarian and the other one is Slovakian," one of the young students said at the reception.

Kozák – in the Washington area earlier this month – said the young artists realized just how easily they could become oppressors or the oppressed.

They’d studied how, in earlier generations, some individuals resisted but others cooperated with Nazis to spy on their neighbors, seize possessions of Jews, or repair the trains that transported them to labor camps.

'Touched by this'

"All of us are touched by this. We still feel the consequences," said Kozák, who was born in 1974. She recalled learning little of that World War II history as a schoolgirl, just like her mother, raised in post-war Communist Hungary. "There is such a cultural silence – taboo."

"Coming to terms with history is a big issue in Hungary," said M. Andre Goodfriend, a former U.S. deputy chief of mission in Budapest. "There’s a lot of polarization within the society and a lot of claims that the government has been whitewashing history."

Goodfriend, now with the State Department’s eDiplomacy office, said the official view, even after Hungary’s sovereignty in 1989, has been "that all of Hungarian society was victimized" during the German occupation. "This causes some friction in Hungarian society, particularly in the Jewish community that knows that average Hungarians played a role. ..."

With the original "Neighbors" exhibit, "we wanted to shake people’s assumptions about what the Holocaust is," said Peter Fredlake, who directs the U.S. museum’s teacher education programs. The student installation "pushes back against the Holocaust narrative Hungarians hear today, one that ignores personal responsibility and claims victimhood."

Talking about issue

Fredlake said that, since the international conference, the other nine countries’ teams also have been exploring social and political contexts for talking about genocide and mass atrocities.

The Hungarian students’ installation is scheduled to travel to the six participating schools beginning in May before moving to other sites such as the International Jewish Youth Camp in Szarvas and to a gallery in Austria.

Workshops and debates are planned for each location. Kozák said she hopes the installation will be seen broadly, for years, because intolerance "is a universal challenge."