A motorboat putters in the falling darkness, the sound of Arabic spoken above the engine. What happens next to the young men aboard is anybody’s guess.

By now, the odyssey of the massive wave of migrants trying to reach Europe by sea is all too familiar, captured on YouTube and nightly news channels. Some become success stories, others find themselves begging on European streets.

Still others have been sent home, and more than 40,000 have died trying to cross the Mediterranean since 2000.

Now, Europe’s migrant crisis is being viewed from a historical lens at a stately Paris museum, with an exhibit focused on the world’s shifting border walls and their imperfect ability to keep people out.

“Borders can appear and disappear, and most which were considered very important, such as the Berlin Wall or the Iron Curtain, are now quite forgotten by the young,” said political scientist and migration expert Catherine Wihtol de Wenden, who helped put together the "Frontiers" exhibit at the National Museum of Immigration History.

Crossing is inevitable

Another lesson of history: All borders are ultimately crossed. “If we control at one point, the migrants will arrive at another,” Wihtol de Wenden said.

Captured through photos, paintings, personal stories and videos such as that of the young men at sea, "Frontiers" looks not only at Europe’s recent immigration history — and the physical and administrative barriers erected over the years — but also at some of the major border walls that exist in the world today, including Israel’s Gaza wall, the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea, and the nearly 1,100 kilometers of fencing along the U.S.-Mexico frontier.

Rather than shrinking, border walls have actually grown since the fall of the Berlin Wall more than a quarter-century ago, and since the 1983 Schengen treaty aimed at creating a "border-free" travel zone within Europe.

“After the end of the Berlin Wall, Europeans thought there would never again be walls in the world,” said Helene Orain, the museum’s general director. “But the reality is very different. We build walls around the world every day.”

The exhibit resonates now more than ever, as new frontiers take shape. In the United States, Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump has called for constructing a permanent wall to stem the immigration flow from Mexico, while Israel reportedly plans to increase the height of its border fence with Egypt to keep African migrants out.

EU-Turkey deal

For its part, the European Union has begun sending illegal migrants back to Turkey under a new deal with Ankara, even as national border fences sprout in countries like Macedonia and Hungary. Across the region, too, high unemployment and fears of terrorism have further hardened attitudes toward immigrants and cast new doubts about Schengen’s viability.

“Public opinion is divided,” said analyst Wihtol de Wenden. “Some people think we need more ‘fortress Europe,’ but ‘fortress Europe’ creates a lot of dead people, and the cost of control is very high.”

In France, the migrant influx and last year’s terrorist attacks have fueled support for the far-right, anti-immigrant National Front party and growing distrust of foreigners. Surveys also show most French oppose accepting new asylum-seekers and believe not only are there too many immigrants in France, but the newcomers have changed their country in ways they don’t like.

Yet even as some French cling stubbornly to the myth of "our ancestors, the Gauls," "Frontiers" underscores the reality of France as a nation of immigrants. There are photos of Portuguese, who arrived in postwar France for work by the tens of thousands, hiking across the Pyrenees in the 1960s and Bohemians being expelled from the country in 1900.

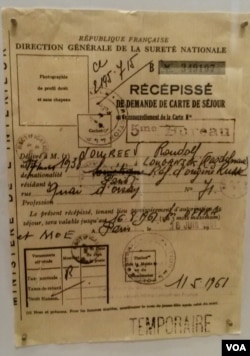

Nureyev's visa

On display, too, is the yellowed visa French authorities gave to star Soviet dancer Rudolph Nureyev when he defected to the West in 1961. There's also a recording of a young Afghan asylum-seeker describing his tortuous journey to France via Turkey and Greece. “Why are there frontiers when we’re made of the same flesh?” he asks.

“Fifty-five percent of French have foreign origins, but I think 10 years ago people ignored that statistical fact,” Orain said. “Things are changing, but it’s a long-term job.”

For Helene Renouvin, 56, visiting the exhibit one recent afternoon, Europe’s border walls have sprouted up in ways that are almost banal. “You get used to it, and don’t realize it,” she said, describing events like World War II, which created new forms of surveillance and identity documents.

Many other visitors draw parallels with the current migrant crisis. “I always thought it was inhumane not to accept them,” said high school student Jinane Dolbec, whose parents migrated to France from Lebanon and Canada. “The exhibit has made me realize this even more.”