At first glance, they do not look like much: tiny fragments of a primordial fungus shorter than a single hair's width. But these fungal remnants possess the unique distinction of being the oldest-known fossils of any land-dwelling organism on Earth.

A study published Wednesday described microfossils of a subterranean fungus called Tortotubus that was an early landlubber at a time when life was largely confined to the seas, including samples from Libya and Chad that were 440 million to 445 million years old.

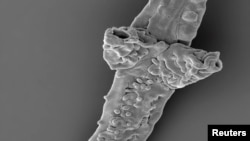

The fossils represented the root-like filaments that fungi use to extract nutrients from soil. Tortotubus possessed a cordlike structure similar to some modern fungi. It was unclear whether it produced mushrooms.

Tortotubus helped set the stage for complex land plants and later animals by triggering the process of rot and soil formation.

"By building up deeper, richer, more stable soils, Tortotubus would have paved the way for larger, more complex green plants to quite literally take root, in turn providing a food source for animals and allowing the escalation of terrestrial ecosystems," said paleontologist Martin Smith of Britain's Durham University, who conducted the research while at the University of Cambridge.

Humble beginnings

These fossils, also discovered in other places including Sweden, Scotland and New York state, reflect the humble beginnings of life on the land.

While the primeval oceans were teeming with life including jawless fish, arthropods, squid relatives, jellyfish and more, the land was barren and void.

To survive on land, organisms had to be able to tolerate desiccation, ultraviolet light exposure and limited nutrients.

Tortotubus may not have been the very first land pioneer, but no fossils have been found of earlier terrestrial organisms.

"By the time Tortotubus went extinct, the first trees and forests had come into existence," Smith said. "This humble subterranean fungus steadfastly performed its rotting and recycling service for some 70 million years, as life on land transformed from simple crusty green films to a rich ecosystem that wouldn't look out of place in a tropical greenhouse today."

Smith studied fossil filaments so small that thousands would fit on the head of a pin. The filaments would have gone through the ground in search of food in the form of dead organic matter.

The original, non-fragmented organism could have been a fungal network measuring yards (meters) across, Smith said.

The research was published in the Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society.