It's about the size of a shrimp, but this little critter may make a big contribution to our understanding of the earliest days of animal evolution.

The animal is called Chengjiangocaris kunmingensis (C. kunmingensis) and it lived during the Cambrian "explosion" about 500 million years ago, when the planet was bursting with all kinds of sea life.

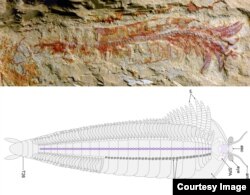

What's special about this little guy is that when a research team from China, Germany and Britain took a close look, it found bits of fossilized soft tissue that turned out to be an ancient nervous system.

Usually, fossils are made up of hard material like shells and bones, so finding any soft tissue, especially a relatively intact nervous system, is a huge find.

The nerve!

The new findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and, according to the study's co-author, shed new light on how the nervous system evolved over millions of years.

"This is a unique glimpse into what the ancestral nervous system looked like," said co-author Dr. Javier Ortega-Hernández of the University of Cambridge's Department of Zoology. "It's the most complete example of a central nervous system from the Cambrian period."

So what did they learn? They found that the nervous system of C. Kunmingensis was a bit like those of its modern counterparts — spiders, insects and crustaceans — but also had some elements that researchers have never seen before.

Simplify, simplify, simplify

Like today's arthropods, C. Kunmingensis had a nerve cord running the length of its shrimpy body, and little beads of nerve cells called ganglia controlling each individual pair of the little guy's legs.

But when they looked closer, they also found dozens of spindly fibers, each measuring about five thousandths of a millimeter in length and showing up pretty evenly spaced along the animal's nerve cord.

The researchers were able to figure out that these little fibers were individual nerves, something no one had ever seen before.

In other words, today's arthropods basically share the same nervous system with their half-billion-year-old ancestors, but one that is less complicated.

That told the researchers that over millions of years, nervous systems may have evolved to do more with less, and the simpler the system the greater the advantage.

For the researchers, it's just another piece in a puzzle millions of years old.

"The more of these fossils we find, the more we will be able to understand how the nervous system — and how early animals — evolved," Ortega-Hernández said.