Louisiana's Mississippi delta is home to several indigenous tribes that have been living on these bayous for thousands of years.

But decades of oil and gas exploration have severely altered their way of life. Now, with the BP oil spill casting an even darker cloud over their future, the people of these bayous are seeking advice from other indigenous groups that have dealt with oil industry disasters, from Alaska to Ecuador.

Crisis decades in the making

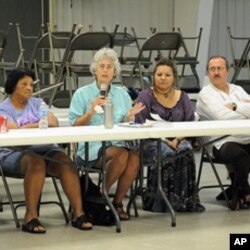

About 100 people attended a recent forum in Dulac, Louisiana to discuss the crisis caused by the BP oil spill. Already, most of the fishing grounds that this community depends on for food and work are closed because of oil contamination.

Inside the building, plastic tables and chairs were arranged in a massive square, as dozens of indigenous people from five countries took their seats.

"It just didn't start with this big BP spill. It's been going on for decades and decades and decades," said the host of the forum, Thomas Dardar, principal chief of the United Houma nation.

Louisiana's wetlands have been deteriorating steadily since the 1930s as a result of the canals dug by the oil companies.

Oil and gas extraction have also caused the land to sink in some places, but nothing of this magnitude has ever hit the Gulf coast and residents here are worried about what it means for a people who live off the land - and the water.

Tribal council Representative Lora Ann Chaison is upset that her community may never be able to fish or shrimp in the Gulf again.

"I have a hard time dealing with this and so I don't know the answer," she told the group. "I don't know if anybody knows the answer but I know that no one can get a straight answer."

Lessons from the Alaskan coast

These communities are looking to people like Riki Ott to give them a straight answer about how the oil will affect them.

Ott has a PhD in marine biology and makes her living commercial fishing in Alaska. She has been studying the effects of the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill for the last 20 years.

"The morning of March 24, we woke up with a tanker wreck, 11 million gallons [40 million liters], we were told. The oil industry under-estimated, made it smaller than what it was, and we have the same thing is happening here," said Ott. "We have this contingency plan that the industry has that says how they are going to clean up after an accident, and we all see here the same as Alaska. It works a lot better on paper then in practice."

When the spill first washed ashore on Alaskan beaches, Exxon told the natives there would be no long-term harm from the oil. Ott says that was not true.

"And we said we would wait until the pink salmon eggs grow up to become adults, they have babies and their babies grow up to be adults. Four years we waited. Four years, the whole eco system collapsed," she said. "The herring collapsed. The salmon. Everything that ate the herring, the whole ecosystem collapsed in four years."

According to Ott, the herring population has still not recovered to the level it was before the spill. "Scientists say it will take 50 years for the oil to leave our beaches and another one hundred years for the clams to come back."

A lawsuit against Exxon was appealed up to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the company ended up paying $507 million - about one-tenth of the original jury award - for damages to the environment and local economy.

Ecuadorean experience

Of all the people who attended the forum, perhaps no one has more experience fighting oil companies than Luis Yanza. He is the lead plaintiff in what is now the largest environmental lawsuit in history.

In the early 1960s, Texaco began drilling for oil in the remote Amazon rainforests of Ecuador.

By the time Texaco left the Amazon in 1992, it had admittedly dumped more than 56 billion liters of toxic waste directly into the streams and rivers of the Amazon. Today, more than 30,000 indigenous people have been affected by the contamination. Chevron purchased Texaco in 2000, and if the court rules against them, they could be forced to pay up to $27 billion in damages.

The company declined to be interviewed for this story. It claims that the responsibility for cleanup lies solely with Petro Ecuador, the Ecuadorian oil company that was a partner in the consortium that owned the wells.

Documenting the damage

Both Ott and Yanza attended the forum, not only share to their stories, but to provide concrete advice for these communities on how to deal with oil contamination.

Yanza stressed the importance of keeping track of the harm done by the oil.

"People need to document the damages and to do it independently, with independent scientists, credible scientists because, at least in Ecuador, when you go to court the decision needs to be based on evidence. You have to prove damages otherwise a company can evade its responsibility."

Residents like Brenda Dardar Robicheux are worried about the aspects of their culture that no amount of money can replace.

"Lousiana is paying the ultimate price for what the world enjoys, for what the U.S. enjoys. The Houma people, all of us living along the coast of Louisiana, are paying the ultimate price," she said. "So I think it's very important that we speak in one very united voice and stand up for our rights as indigenous people no matter what country we represent, what area we represent because our very existence, our very way of life is being threatened."

There are still many unknowns regarding the long-term effects of the spill but, for the United Houma nation, this is likely the beginning of decades of cleanup and litigation that will determine the fate of a fragile community on the brink of survival.