In Washington state's Olympic National Park, the biggest dam removal in U.S. history is under way.

Tearing down a pair of tall hydropower dams along the river has been talked about for 25 years. Action is finally being taken.

Heavy excavators are digging a channel to re-route the Elwha River. The 72.4 kilometer-long waterway has been blocked by the Elwha Dam and Glines Canyon Dam for 100 years.

The dams have decimated the river’s abundant salmon runs. Removing the structures will allow the fish to return to their historic breeding grounds in the upper part of the river.

No way out

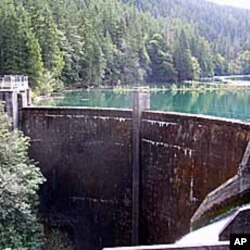

At the lip of Elwha Dam, one can hear the Elwha River gushing out of a spillway and crashing down 32 meters into an emerald, green pool at the base of dam. When the sun hits the water just right, you can see salmon in the pool - circling aimlessly at the foot of the dam - still looking, after all these years, for some way over.

It's been 100 years since Elwha Dam was constructed. It was built without fish ladders. Because of that - and those frustrated salmon below - the dam's days are numbered.

The preparations for dam removal are under way upstream and downstream. This September, contractors will dig a channel through a delta of lake sediment to help the Elwha River find its original course.

Olympic National Park spokesman Dave Reynolds watches a barge as it ferries heavy equipment for that effort across Lake Mills, the manmade reservoir behind the dam. The lake is gradually being drawn down.

Back to nature

"It is symbolic and it seems like a lot of people are really excited about it," says Reynolds. "This seems like the first major project right on the Elwha. It's changing the landscape. It's got a lot of people really looking forward to next year and the beginning of dam removal here."

There are people who will miss these two dams on the river and the lakes they created.

"I like the way it is set up right now. It's been this way so long," says sport fisherman David Mead as he casts for trout below Glines Canyon Dam. "I just personally don't see the need to tear those out when we've got so many other rivers for the salmon and the steelhead and everything."

However, Mead recognizes the debate about tearing down the dams is over. "Hopefully it's all going to be for the best when it's all done."

'We want our dammed salmon back'

The Lower Elwha Klallam Indian tribe set all this in motion back in 1986. That's when the tribe challenged the relicensing of 64-meter-tall Glines Canyon Dam and the 33-meter-tall Elwha Dam.

The rallying cry is stitched into a logo on tribal member Robert Elofson's jacket. It features a pun on a common oath.

"It says, 'We want our dammed salmon back.' That's d-a-m-m-e-d," says Elofson.

Elofson directs the Elwha River Restoration Program for his tribe. He says dam removal will open 112 kilometers of river and tributary habitat. Salmon have a central place in the culture and diet of many Pacific Northwest tribes.

Signs of new times

On the Lower Elwha reservation, rumbling convoys of dump trucks signal the decades-long wait to free the river will soon be over.

The trucks also drive home what makes dam removal so expensive and complicated. Among other things, contractors are raising levees to protect reservation housing from a less controlled waterway.

"The river level will be higher, the groundwater level and the flood levels will be higher," says Elofson. "So the levee system has to be modified and expanded."

American taxpayers are also paying for a new fish hatchery. It will shelter the remaining Elwha salmon during the dam removal process.

"We've worked very hard to get where we are and to get this project done," says Elofson. "You know, we take a great deal of pride in the fact that it has been accomplished."

More to come

Actual deconstruction of the concrete dams starts next year.

Several other dams around the country are slated to be torn down next year as well. They include Pacific Power's 38 meter tall Condit Dam on the White Salmon River in southwest Washington State. On the East Coast are a dam on Maine's Penobscot River, a stronghold for Atlantic salmon, and Simkins Dam on Maryland's Patapsco River.

Supporters say removing outdated dams improves water quality and public safety while expanding recreation opportunities and benefitting fish migration.

The surge of activity prompted the environmental group, American Rivers, to dub 2011 'The Year of River Restoration.'